This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 3, "Growing Up Southern." Find more from that issue here.

“We started thinking of family day care,” says organizer and parent Leslie Lilly, “because center-based day care just didn’t seem feasible. We didn’t have the money it takes to put up a day-care building which would meet the rigid state requirements. It seemed that a less urban solution would work better anyway, for our rural area.”

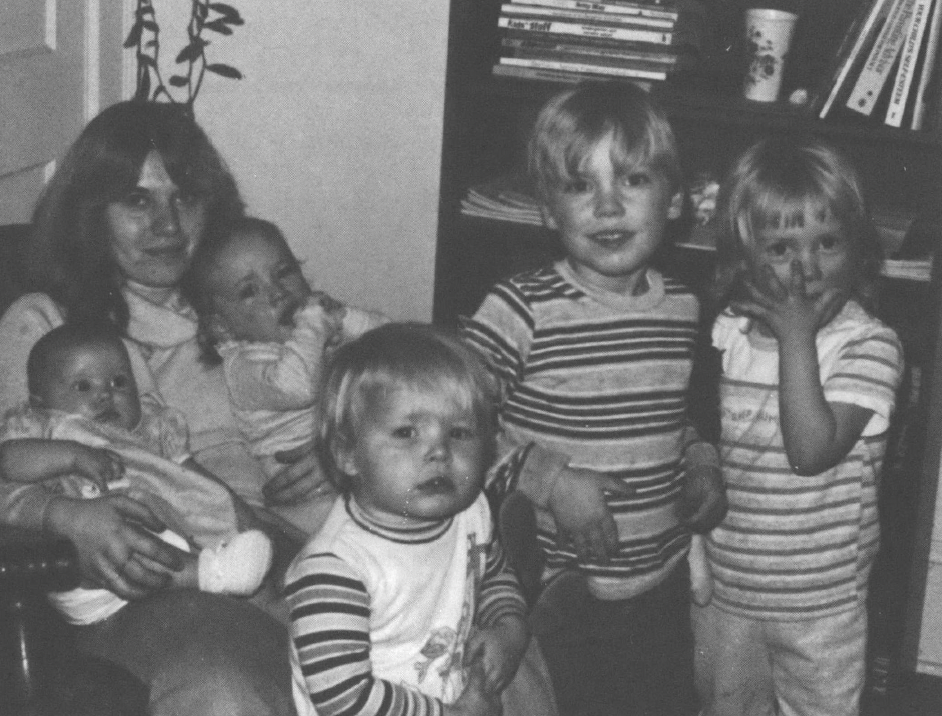

Today, the Blue Ridge Child Development Family Day-Care Center that Leslie Lilly and other parents helped establish in 1977 in Blue Ridge, Georgia, serves over 70 children in a network of 14 day-care homes throughout the county. The day-care mothers — caring for four or five children in their homes — are not directly employed by the Center; the Center selects and trains the mothers and then refers children to them. The Center’s central office is staffed by four full-time professionals who offer training, support services and a variety of equipment — books, records, learning toys and even Peabody language kits — to the providers. “Our big push is to help them provide real child development — not just babysitting,” says child development specialist Cheryl Brown. “We pop in to visit a lot, too. Then we’re always available if there’s a problem; they can call up and say, ‘what can I do, this baby won’t stop crying,’ or whatever. But basically it works real well. It’s child development, but it’s in a more home-like setting than you would get in a day care center, and there’s more opportunity for individual attention. The children can really feel like they’re in a home away from home.”

Blue Ridge is a small community (population 2,500) in the mountains of north Georgia. It’s the seat of Fannin County, and the hub of business and services for the county’s 13,000 residents. Although new industry, and new jobs, have been moving into the area in recent years, wages for many workers there — particularly women — still hover around the minimum wage. The main employers are several textile mills — including a Levi Strauss plant employing about 500 women.

Levi Strauss has played a crucial part in the Center’s history. After working for two years on developing and refining their proposal for a family day-care program in Blue Ridge, Lilly and a group of other community residents succeeded (in 1976) in obtaining an initial grant of approximately $30,000 from the Levi Strauss Foundation to set up the office. The Blue Ridge group got a helping hand in drafting the proposal from a staff member of the Save The Children federation in Atlanta; Save The Children also donated office equipment and served as the funnel for the Levi Strauss grant.

The Center staff puts a major emphasis on the selection and training of its child-care providers. It holds three-day training sessions for each new group about once a year, “or whenever we need to,” says Brown.

“There are basically two ways to approach family day care,” says the Center’s former director, Jim Clark. “One way is to find out who the providers in a community are and just get them together in an association; there’s not much monitoring involved, and not much training. Our program emphasizes selection of good people to begin with, and then they get a lot of in-service training from Cheryl and from Jeanne Hudson, the administrative assistant. This eliminates the horror stories.”

Cheryl Brown agrees: “It’s a harder program to administer than a day-care center, where you have everybody all together in one place. You need to do a lot of monitoring. But family day care is so much more flexible than center care; we can provide for the parent who needs child care during a night shift at a factory, for instance.”

The family approach taken by the Center is reflected in its many pronged parent-education program, which includes pre-natal education, prepared-childbirth classes (“People drive for 50 miles to the childbirth classes”) and even a “Family Living” course (sometimes called sex education) for the public schools, aimed at reducing the county’s unusually high teenage pregnancy and infant mortality rates.

“We set up the program from scratch,” says Clark. “There were a lot of initial tasks getting organized; we had to apply for tax-exempt status, open corporate books, purchase various insurance policies.” Future funding was also complicated; Levi Strauss had made the grant specifically as “seed money,” expecting the Center to become financially independent after one year. “But it’s just not that easy,” says Clark. “A director has to be a wizard, juggling different sources to come up with the necessary funds. And there’s no central source to go to, so you have to expend a lot of energy in writing proposals, and that takes away from the time you can spend on the program. Everybody just wants to give seed money, so you have to look like that’s all you need. It’s a catch-22 situation. And it’s because child care is not a priority in this country.”

By a combination of circumstances (“part luck, part skill,” says Clark), the Center succeeded in April, 1977, in getting Title XX funding for the project. “I picked up a pamphlet one day,” remembers Clark, “which said that the Georgia Title XX office was accepting new applications for the first time in years. So we got our proposal in right away, and got it approved, and soon after that they stopped accepting applications again.” Title XX pays for the office budget (annually around $66,000), as well as paying fees ($22.50 a week) for the 40 children who qualify. Almost all of these children are supported solely by single parents.

The other children (who don’t qualify for Title XX assistance) pay fees directly to the provider. “It’s up to the individual provider, what she wants to charge,” says Cheryl Brown. “When parents come in looking for care, we talk to them about their specific needs, and then give them a list of the providers who are available and suitable. Then they visit the providers and decide which situation seems right. So far, we’ve been able to keep up with the demand, so parents don’t have to go on a waiting list.”

Title XX pays for medical and dental screening for the children who qualify, and a grant from the Appalachian Regional Commission covers follow-up treatment for problems diagnosed through the screenings. A USDA food program, which reimburses the providers for the money they spend on food for the children, is available to all the providers, independent of the Title XX program. Each provider turns in a record of the menus she serves — including snacks — and if they meet certain standards for nutritional balance they are reimbursed. Jim Clark says the USDA program has helped cut down on anemia and other diet-related deficiencies among the children.

People seem more willing to accept a federally funded day-care project if the providers are their own neighbors, says Brown. “We met with some suspicion at first. We put up a sign at the Levi plant that said, ‘Free Child Care,’ and still people backed off. But when they hear that so-and-so who lives down the road is in our program, and she’s so-and-so’s cousin, and she’s really good, then they feel better about it. We’ve built up a pretty good image in the county by this time. We’ve held covered-dish suppers and field days, and we’ve had good cooperation from the press.”

The providers, too, enjoy being able to earn a decent amount of money while retaining the privacy of their homes, Brown says. “We do a lot of monitoring and training, but they’re not under anybody’s thumb. They can arrange things to suit their own needs and the needs of the children they’re caring for, which they couldn’t so much if they were working in a big day-care center. Sometimes, there’s a case where the provider’s husband doesn’t really like the situation of having other people’s children in the home, or expects her to keep up with the housework just as well since she’s working at home. But we haven’t had very fast turnover among the providers at all. Several people have been with us since it started.”

For the first three years of its existence, the Blue Ridge Center was able to use the original $30,000 from Levi Strauss as the local “seed money” that Title XX requires as 10 percent of the operating budget. But starting sometime in the next year, they’ll have to come up with a new source for that funding. The grant for the parent education program from the Appalachian Regional Commission also runs out in October, 1980, as it too was given as seed money. So writing new grant proposals looms once again as an urgent priority for the Center.

“I don’t think child care is in very good shape right now,” says Jim Clark. “It’s not well-funded, and it doesn’t look as if that’s going to improve anytime in the near future. I don’t think that self-sufficiency is a realistic goal for a program like this. There’s just some things that the private sector cannot take care of. The public has to realize that we need to do them, anyway, and be willing to pay for them.

Tags

Southern Exposure

Southern Exposure is a journal that was produced by the Institute for Southern Studies, publisher of Facing South, from 1973 until 2011. It covered a broad range of political and cultural issues in the region, with a special emphasis on investigative journalism and oral history.