This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 3, "Growing Up Southern." Find more from that issue here.

Portland, Kentucky, is a hard-living little town, rich in culture and history, but also fraught with trouble and pain. Now a pocket of urban Louisville, Portland sprang up originally as a crossing place on the Ohio River, where travelers had to stop either to portage around the Falls or to cross the river. Until the Louisville Canal Company diverted the waters of the Ohio, thus directing commerce away from the Falls, Portland flourished as a river trading post. Then, one by one, the old outlying farms were sold off. Company “shotgun” housing was erected; factories and warehouses hemmed in and defined the area, and the town became a neighborhood of Louisville, which had gradually engulfed it.

Portland has strong flavors of both the river and the country. You can taste the river in the drinking water; it floats in on the floods. But the country flavor comes from the people. Many family roots still penetrate deep into rural Kentucky. Portland is often the first and last stop in a country-to-city migration pattern, and families still make frequent visits to their relatives back in the rest of the state. When asked what they would like changed in Portland, many children wish for more trees and green things; for it to be more like the country. The harsh patterns of urban life still anger and grieve them. “You get mad sometimes at people, especially if they stab your cousin or something,” says one eight-year-old.

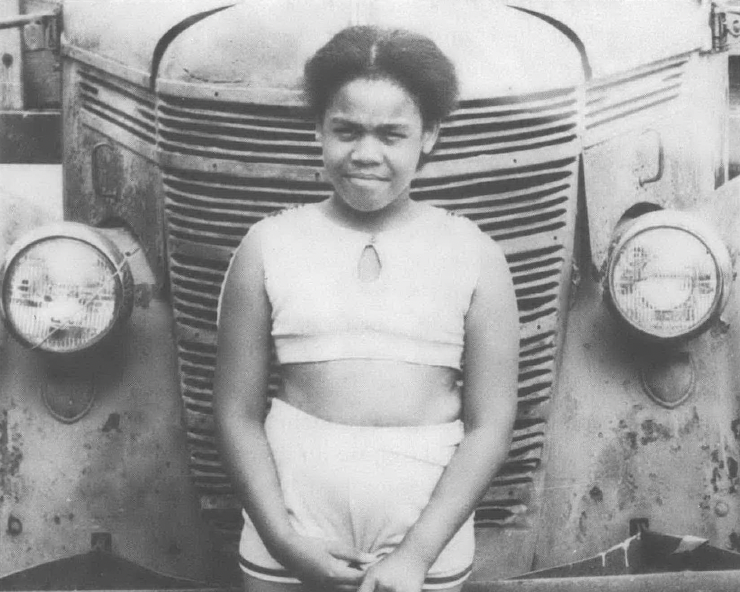

Yet there’s a brighter side as well: a strong sense of community strength and solidarity; a pride in the neighborhood's history and its institutions. Eight of Portland’s children talked recently about their community and what it means to them and their families. What follows is a portion of that conversation. All the children are between eight and 10 years old; six are white and two are black; they attend Roosevelt Community School in Portland. Their names are Dorothy Branch, John Branch, Michelle Brooks, Sheila Cheatham, Richard Harlow, Eurana Horton, Ricky Marshall and Calvin Oakes. The accompanying photo graphs are also by Roosevelt students, made through a program at the school’s Portland Museum.

Well, in the olden days, that house we live in, it’s still there and we still live in it. I don’t think we’re ever going to move. We have a picture of our little sister, of my little sister Tracy, running up the steps. She was two years old. She’s running up the steps with a little white doggie in her hands. Mom and them took a picture of her.

And my grandfather and grandmother moved there and they had my mother, and my mother had Kelly in the house - in them days when the doctors come to your house and delivered the baby. She almost died. She was so small. Mama’s lived there all her life. Never moved.

Remember when we had that hunt last year for a house that you could shoot a gun through and it would go straight through the front and straight through the back? We got that kind of a house. It’s like a train house. . . . It’s got three rooms in it. The living room, bedroom and kitchen and bath. But, in the living room, we had to put our bunk beds in there. And one day, I was getting off my bunk bed in the middle of the night to go use the bathroom. Right on the first step and my feet slip. I was in the room where the furnace was. That thing went like a ton of bricks. Yeowww. And woke up my mom and dad. And then later on my mom moved our bedroom into where their bedroom used to be and now that’s the living room.

Our rent-man is a PUNK. Yeah, he’s silly. My mom’s been asking for screen doors for the last three years and he hasn 7 got them up yet. He brung one screen door for the back door and it didn’t fit. Then he was going to put it on the side because it just fits. Just that the side door don’t have no steps to it. And then you have to step up a step about that high to get in the house. The side door about that high. And so he left it and didn’t put it up. He left it out back, so my dad put it in the shed and then he took it back out for he thought it would get too dirty in there. Now it’s sitting up on the porch and my mom’s been asking for a fence and he got the wood down there and put it in our shed, but he hasn’t put our fence up yet and she’s asked for that two years ago.

I’ve got two sisters, my mom and my dad. . . . My big sister, Melanie, she’s I believe, 11, and my little one’s eight. ... We use the whole house almost. There’s one room upstairs the man don’t want us to use because the roof is falling in. ... We tried to buy it, but we couldn’t. Daddy said if we got another house, we’d keep it clean and stuff.

I’ve lots of sisters and four brothers, counting my dead one. And they all live at our house except my sister and my brother and my other sister and they fight with me a lot. But I have to tell my mom and she whips them. My two big sisters, they sleep in a room and me, my brother and my other sister, we sleep in a room. Sometimes we fix up the rollaway bed and we sleep on the couch. We sleep on the chairs and we sleep anywhere. Well, I sleep with my mom sometimes and when my dad’s home, I don’t sleep with them. But, when my dad’s not home, I sleep with her sometimes.

We’re having nine people over to our house for Thanksgiving. My mother put the menu up this morning. We’re having — my grandmother’s fixing chittlings. My mother’s fixing ham and turkey. We’re having potato salad, macaroni and cheese, deviled eggs. We’re having Kool Aid for the kids and tea for the grown-ups.

One time, I was real small, and I wanted a doll and I was by my grandmother's house. My mother said she wasn’t going to get me one. I told my grandmother that and she said, “Go lie down for a little while, baby. When you wake up, you ’ll have a doll.” When I waked up, she had made me a little doll herself.

My grandpaw died in a car accident. He was coming back off the expressway to get some more wood for the house and there was two people on each side of him. They was drag racing on the expressway and he was right in the middle of them, and he, he, they hit his car. They rammed into him and his car went out of control and he went into the wall and died. ... I don’t have any grandfather.

My mother said, when I get old enough, if I wanted to, I could live in the country, because she says she might be moving to the country because it’s a little quieter. We live by the expressway and we hear all the traffic noise.

I got some people in the country. My aunt and my cousin, my mom’s friends — whole lot of them. We go to see my Aunt Doris and I talk to my cousin Gail and she usually gives us money and stuff. She got married, Gail did... I wish I could go up, stay with her a week.

My dad works at Linker’s bakery and so does my uncle and so does my other uncle. My aunt used to but she don’t. They make buns and stuff. My dad messes with the dough and puts it in a machine. He’s been there about 16 years. My mother used to work down there on Crittenden Drive at this printing company, The Printing Press, that’s what it’s called. South or Southern Printing Press. 1 can 7 get the rest of it. She worked but we stayed with our aunt until she got off. She can’t work now because she’s having another baby.

Dad works in a mill. He runs a big ole machine. He makes it go round and round and he wraps the spools up. Some of them are about 7,000 — 5,000 pounds. Thirteen thousand pounds in two of them. This one man, this colored man, he tricked them. I believe his name was Mozeek. And he heard one of them things go and he wasn’t hurt. That man was lying down on the ground and groaning and moaning. And then my dad came over there and saw him and saw that he wasn’t hurt. He done scared him to death.

My dad is a fireman and I’m going to be a doctor. My mom is a housewife. Dad’s been a fireman 19 years and he really likes it. Sometimes he takes us to the firehouse and lets us go in a firetruck and gives us a Coke. And he goes to Shamrock’s every time he gets off work. He don’t come straight home. He goes to Shamrock’s for four or five hours, then comes home to eat supper and goes back to Shamrock’s.

Shamrock’s is a nice place. People’s supposed to fix the upstairs up and move in. Then Nemar might sell the upstairs and make them a doorway. . . . He lets me play pool and stuff. . . . Some of them buy me stuff, me and my friends and my cousin, about 12 people. No women can come in. Last time they let women come in, they were looking for their husbands. People got in a fight in there, and stuff, and then they tore the place up, so they had to put a sign up, “No Women.”

Shamrock’s is, I don’t know, 25 years old. People used to live in it. It’s got signs hung on it. Great big old whiskey bottle that says Seagram’s Seven on the side. Then it’s got a sign out front with .22 bullet shots in it. Guys had a gun-shot fight. Hit the sign. Me and my friend John Ryan might get Shamrock’s when we grow up. We just gonna leave the same signs up or else get some new ones just like it. We was going to leave all the trophies in there. . . . Well, they got basketball trophies. Trophies hanging up, picture of horse races, football helmets, long-time-ago football helmets. They got one worth 200 dollars.

Lannan’s Park is named after my grandfather, and his picture is in Nelligan Hall and we got a picture of him at home with some other people. My grandmother and my mom, she goes to Nelligan Hall on Fridays and Saturday meetings there. My aunt Katie, my mom’s sister, she has the key to the place. And she’s got a key to the little bus and we go camping in summer. You can take a whole truckload for a dollar and a quarter, if you can get them in.

Well, they have lots of pictures in Nelligan Hall of my grandfather, my mama’s dad, my mama’s father. See, it’s owned to the public. We have bingo there on Saturday and pinochle and playing cards on Fridays at seven, ending at one or two o ’clock in the morning. See, it’s not for little kids, it’s just for adults. But we can play bingo and stuff. See my brother, he won, let me see, a hundred dollars there once. Then he won 20 dollars there once. And one time I won 29 dollars there. Well, we had a party over there for my cousin Mary Lannan. See, cause she’s going to the army. We had it Sunday cause she’s going Friday. So she went and left her car with my uncle. My Uncle Dickie. He lives across the street and it’s a cute car. We had a good party for her.

We’ve got a club and a clubhouse. What’s those things where you call a spirit? We had one of those. We couldn’t pronounce the name. We forgot what the name was. We had one of those. We was down in our club, down this block. So we said, “Terry, if you’re here, tap us on our shoulder and make something fall in the club.” And we turned around and the whole table fell. It stands this tall and that thing just fell over to the ground. We were in the backyard and we said, “Terry, if you’re here, make a noise.” And I swear, am I lying Nathalie, something said, he said, “Don’t-you-go- back-in-that-club.” Come on, something said that. Scared us. We took off running out front. I didn’t believe in that stuff until yesterday. Something said, “Don’t-you-go-back-in-that-club.” We were all shaking yesterday.

The Roosevelt Community School is a lively and valued part of Portland. In the early 1970s, a Neighborhood School Board was formed in the community (under the Louisville School Board) with real powers to hire and fire teachers and to evaluate the school’s programs. And the Portland Museum - a special part of the school, and a strong bridge to the adult world - was created to help the children discover, uncover and preserve the history and culture of their neighborhood.

Yet despite the fact that the Roosevelt Community School has become a model for community involvement admired by school systems across the nation, it has become the target of increasing attacks from the Jefferson County Board of Education. Roosevelt serves a racially balanced population and so is exempt from busing. But the Board of Education charges that the school building is rundown and would cost too much to fix, and since 1976 has tried seven times to close the school and bus its students out of the neighborhood. So far, with determined support from the whole community, Roosevelt has weathered these attacks.

Tags

The children of the Roosevelt Community School

Nathalie Andrews

Nathalie Andrews is Interim Director of Roosevelt’s Portland Museum.