This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 3, "Growing Up Southern." Find more from that issue here.

Two years ago my new job as Artist-in-the-Schools in Braxton County, West Virginia, offered me the opportunity to return to my home town of Sutton after an absence of over 14 years. The Artist-in-the-Schools program was supported by grants from the National Endowment for the Arts, the West Virginia Arts and Humanities Council, the Polaroid Foundation and local sources.

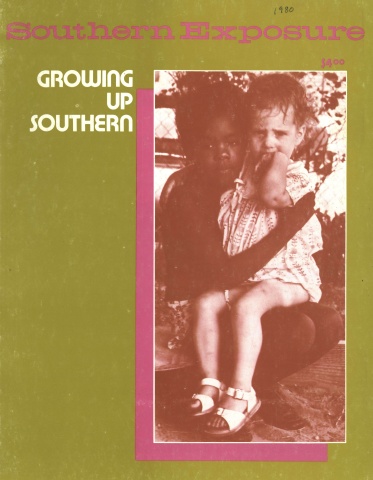

The photographs were made by public school students 10 to 14 years old. This is a wonderful age to begin taking pictures. Photography offers kids a chance to frame experience — that is, to hold it apart for special consideration, and then to “frame” it again in an exhibit or magazine to be considered by others. The medium is personal, non-verbal and widely accessible. Many students who are hesitant in speaking and writing are immediately successful at self-expression with a camera.

I encouraged the students to respond to familiar subjects and to work with feelings. Their ability to tap these sources enables many students to transcend the limits of simple cameras or the lack of refined technique. Photography is first of all a process of understanding what one sees. Walker Evans says of the camera, “You have to really know something before you dare point it.” These young photographers in Braxton County automatically have two things professional artist-photographers are always striving for: intimate access to powerful subject matter and a fresh point of view. The camera offers kids a chance to trace personal experience in an instant.

I believe that some children are visually gifted and that their gifts have been received without regard to intellectual ability. For this reason, I usually chose my students at random. Except for two special education classes taken in their entirety (educable mentally retarded and intellectually gifted) and one instance when I asked the teachers for “non-impulsive types” (I got a random selection anyway), I literally walked into the classroom cold and drew names out of a hat.

Further, the camera provides all young people with a means of receiving an occasional visual gift regardless of their artistic backgrounds or previously acquired manual skills. Although much that happens in student photo graphs can be termed accidental, I believe much more of it is intuitive. Through photographs kids are easily able to show us what they care most about. (This became easier still for our younger students when they switched to Polaroid.)

Finally came my responsibility as editor of the student work. I felt it was important to remain true to the simple moods of quiet contemplation and youthful exuberance the students enjoyed while actually working with their cameras. I tried not to present the photographs in a manner the workers had not intended for their product. Photography (and editing) has tremendous potential for misuse and for exploitation of the subject. The camera can make almost anything appear foolish and unimportant; but these are all positive images, sympathetically observed, presented for our appreciation. Emmet Gowin says he thinks of his photographs as “agreements,” as a “natural duty” to honor the person who agrees to reveal himself or herself. The subject entrusted his or her image to the photographer; the photographer entrusted it to me; and now I am entrusting it to you.

Many years have passed since I sat in the same classrooms. Because I had been here before, the project held a special magic for me that it would have held in no other place. I believe in this place; and I believe in these kids partly because I see in each of them potential, see myself at an earlier time. By offering them photography I offered them my means of seeing and dealing with a special world we have in common; and I fulfilled a promise to a 10-year-old kid I once was.

Tags

Robert Cooper

Robert Cooper is currently an M.F.A. student at Rochester Institute of Technology. His personal photography has been published in Appalachia: A Self-Portrait, by Appalshop, Inc., Whitesburg, Kentucky, 1979. (1980)