This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 8 No. 4, "Winter's Promise." Find more from that issue here.

If there hasn't been any rain to speak of, as there hasn't been, you know a load of potatoes is coming as soon as the truck rounds the first bend, 10 acres across corn fields. If not, you have to wait for the second curve when you can actually see the truck and not just the dust that blows up from its wheels.

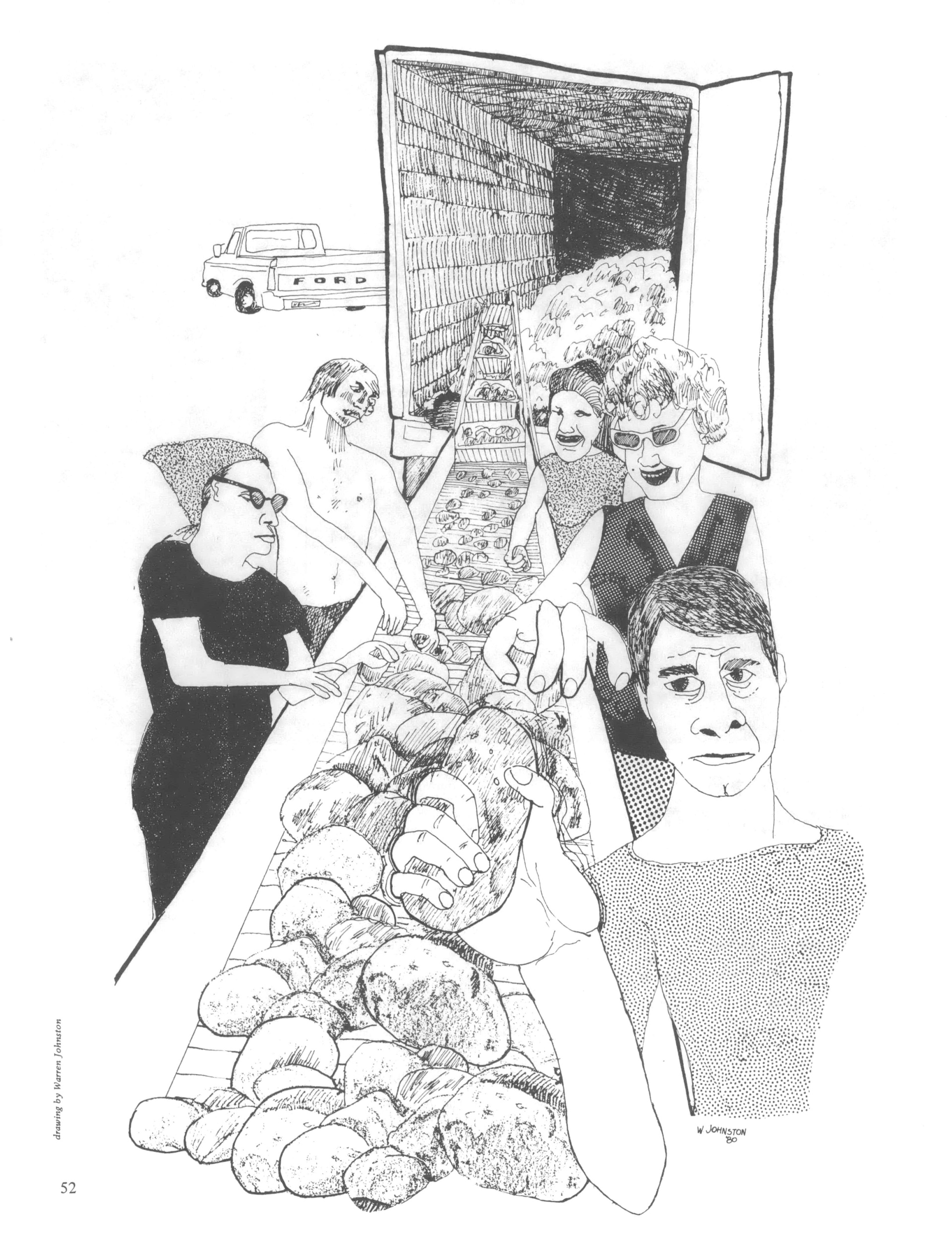

Depending on the driver, from that second curve it takes between five and 10 minutes before the truck is backed up to the grader, the tray that catches the potatoes adjusted to the right height, the electric motor hooked up, and the electricity switched on. On the tray the potatoes are carried by rollers to a second conveyor of hexagonal metal through which the smaller, or “B” potatoes, drop. The “A”s alone pass onto us, the human graders, and from these “A”s we throw the sliced or rotting ones, the dirt clods and compressed beer cans, grass, snakes and turtles — throw them out fast before the belt narrows and the boom loads them onto the tractor trailer which will deliver them eventually to Indiana, Ohio or Pennsylvania and to their ultimate destiny: chips.

It takes four to four-and-a-half field trucks to fill one tractor-trailer load. The most rigs loaded in one day has so far been seven; the best time we’ve managed for one is two hours even. But that was a day when loaded field trucks were parked next to the grader waiting on us, not a day like today when we turn again and again toward the road to see only the clear rising currents of undulating heat, no dust.

Five of us work the grader — two male, three female. One operates the motor at the tray, the other four sort through the potatoes rolling by. Today, in the third week of digging, in oppressively still July, we are again at a stall, a stall that has stretched beyond an hour because not one but both of the diggers are broken. There have been other breakdowns: pulleys, tractors, trucks, motors, but a broken digger is the most dreaded, the one which causes the longest delay. When a driver brings in the news from the field (“one digger’s broke and the other won’t work,” as one fellow put it), the 10-hour day we had hoped for automatically lengthens. “Lucky to get out by midnight” someone says and the phrase gets picked up and repeated again and again. Bad news for all the high schoolers who thought maybe tonight they could slip in a date, bad news for my swollen ankles, bad for the long-distance truckers whose schedules become even tighter. Worse still for the farmer who can see at least five on his payroll sit and do nothing because the dirt from beneath the grader has been shoveled, the stray potatoes reclaimed and there is nothing left to do but wait: the trickle of sweat and the trickle of money slipping away. “That’s potatoes for ya,” someone says philosophically, and indeed it seems to be. Into the third week, not much new gets said but there are always the appropriate repetitions. Complaints about the size of the potatoes, the heat, the dust, the tiredness. Also: feats — both engineered and imagined. “Son, you wouldn’t of believed how much I drunk last night. I swear to God, son, I woke up this mornin didn’t know where’n the hell I was.” There is general consternation that the season — potato season — won’t end before football season begins. “Hell, I’ll quit, son, I gotta have me some time to party.” From the females the talk is more speculative: who of their peers is and is not careful. “She just wants to get pregnant so he’ll marry her. And you know he will. That’s all she wants.”

Another 30 minutes pass and still there is no dust, no word as to when we can expect any. The long-distance truckers stretch out under their trucks or climb into their cabs, turn on the air conditioning and try to sleep. I walk over to the office to wait it out. The son of the owner of this operation is to be married in August, “after these potatoes are in,” says his mother who is, like the rest of her family, working here six days a week for the duration. There is wedding talk to cover up potato talk: how badly the lack of rain has hurt them — 200 bags to the acre last year and this year not even 150; how much money the breakdowns are costing; the more serious cost of supplying contracted potatoes that are not in the fields and will have to be bought elsewhere at a higher price to make up the deficit. The mother of the groom will wear blue, she says; the bride’s mother will be in pink. China and crystal have been picked out but no silver. Then someone outside spots the dust. “Potatoes,” he calls, and we put on our gloves and return to the contraption which looks like a mechanical ostrich, but the potatoes as yet are only at the second curve.

We know who is driving the truck before we can see him because it takes Eddie Rose just under five minutes to get around that second curve and park his truck at the tray. On the last turn he makes a practice of driving two-wheeled. Even in reverse he doesn’t slow down, but he is the only driver who never slams into the tray.

During the two-and-a-half weeks that I have been attending to the movements and mannerisms of Eddie Rose, he has begun each work day wearing bib overalls and a T-shirt. By the first truck load he has shed his T-shirt and by the second he has unstrapped the bib and is in danger of losing the overalls altogether. He is, as they say around here, a “big boy” although he is 20 years old and hardly a boy. The big is more appropriate: six foot at least, at least 220 pounds. Usually he farms with his father but because their peas were already planted and Baxter needed him, he’s working the potato season here.

“Goddamn it’s hot,” he says, slamming the cab door and walking somewhat slewfootedly to the thermos from which he doesn’t bother to drink; instead he pours water over his entire dust-coated face. Then he climbs up to help us. He grades without gloves and with a cigarette dangling. If he’s run out of cigarettes and can’t bum one, he sings Barbara Mandrell hits with the other two women. He is a devotee of the local country music station, its bumper sticker pasted on his red Ford pickup equipped with stereo and headlighters. We discover amid the roar and haste that his cousin was in my high school class.

Cigarette still dangling, he cocks an eye.

“You that old?” he says.

I am.

The next question is no surprise either. Why am I grading potatoes? I have found it best to keep the reply simple.

“Broke,” I say.

Within the pause he throws out more dirt clods with one hand than any of us do with two.

“Lemme ask you somethin else. You married?”

Community rumor has it on its files.

“Was,” I say.

There is no need to try to cover over awkward silences on a potato grader; there are no awkward silences. There is always an overwhelming, unrelenting mechanical grind.

Only occasionally, and just occasionally since I’ve been away from this place, do I run into an Eddie Rose. Since Jimmy Carter good ole boys have been cast into a glaring limelight and — as with all media-blitzed types — they are done an injustice. Finally they are only themselves with a few commonalities. The tendency to brag, to retain a Dark Ages concept of womanhood, annoys. But there is also a very pure and rare simplicity to be found among them, a simplicity bred from innocence — not of the rawer elements — an innocence of vision: of what things are, what they mean, what they should be. It is a simplicity and innocence the South as a region can no longer claim and perhaps because I feel it disappearing so quickly when I’m here I clutch at Eddie Roses, turning a blinder eye than I might toward annoying traits in fear of destroying others.

To say any of this to the real Eddie Rose would no doubt bring his freewheeling style of storytelling to an embarrassed halt. There is no reason to tell him. Instead I try to talk with Eddie Rose about more than the size of potatoes or the thickness of dust. I try and perhaps because I have answered him, he answers me no matter how strange my questions may seem.

The reason he will register for the draft is that he couldn’t produce the $10,000 necessary to cover the fine should he not register. But if he were drafted he would serve. “Yeah, sure. It’s my duty.”

His truck is empty of potatoes and after he pours another pint of water down his face, he jumps into the cab and guns the motor, off to the fields for another load.

“Crazy fool,” says one of the guys of a “boy” who has been driving tractors and field trucks and shooting rifles since he was eight. Crazy Eddie who guns the motor again approaching that second curve.

Jeremy Carl Something.

I never do catch his last name, he gives it so quietly. In the past three weeks I have seen all types of truckers; one who brought along his wife and their two little girls; one who looked like someone’s Puritan grandfather, bespeckled and hunched and complaining of cold in his chest; one who wore a black studded cowboy hat; several who had tattoos; one who was accompanied by an obvious runaway and during the boredom of another stall, turned over his cab doing 75 in a 45-mile-an-hour curve, but neither he nor she was hurt. Several are so very ordinary I forget them almost as soon as they leave but it is unlikely I will forget Jeremy Carl, his blonde hair under a baseball cap, his blue eyes under sunglasses, his bafflement at the world post-Viet Nam as yet without suitable disguise.

He is not a Southerner; he is from Ohio. He says “worsh” for “wash,” and the story that is pulled out of him is done so in bits and pieces by potato graders who have nothing else to do but inquire. When prodded, he tells how to dodge road regulations when driving without a particular state’s license, how the potatoes are harvested in the Dakotas. But he is no storyteller. He pauses too often and too long. And he listens. And sometimes something will slip in without the twist of humor or dramatics; a son named for him, a woman who would not stay faithful, jobs that didn’t pan out and finally Viet Nam because I persist.

The recitation is almost rote. He was there for 17 months. He drove a truck. One day he and his buddy drove over a land mine. It killed his friend and six months of his memory. What he does remember is the dampness of the climate, the human feces floating in the ditches, the Viet Cong’s clever trick of turning mines and sending a herd of water buffalo through before they themselves attacked.

“I don’t know if I ever thought of not going,” he answers. “I don’t know but I don’t think so.”

The lights of a field truck are spotted in the gathering darkness. This last load will fill his quota and after it all of us can leave the dirt and noise and fierce mosquitoes and call it a day. The digger crew and drivers have already completed their end of things and while we pick through the last of the “A”s, Eddie Rose punches out, jumps into his pickup and barrels onto the black highway.

When the last of the potatoes drop off the boom, Jeremy Carl closes his gates, inspects the locks on his back doors, tests the lights all around and tells each of us goodbye. He also turns onto the black highway but when he does the acceleration is slower, more even; the night he drives into longer and more keen.

The last potato was dug on July 23, a week before Eddie Rose was required to register with the Selective Service System in accordance with the Military Selective Service Act and was asked to record for them his date of birth, sex, social security number, telephone number, current mailing address and to attest to the fact that he was, at least until they sent him elsewhere, a permanent resident of Currituck County, North Carolina.

By signing on the dotted line, he swore to the veracity of all foregoing statements and by doing so, also indicated that he understood the Privacy Act Statement as printed on the back of the registration form.

There was no space provided in which Eddie Rose or anyone 20 years old might pencil in other things they understood or didn’t understand so that such information might be kept on file should memory become impaired or should one day they begin to quietly wonder about duty; about why their notion of it and everything else had somehow changed when before all had seemed so simple.

Tags

Kathy Meads

Born in eastern North Carolina, Kathy Meads has published poetry and fiction; this essay is part of an in-progress work entitled Notes Accompanying Wanderlust. (1980)