Bloody Summer

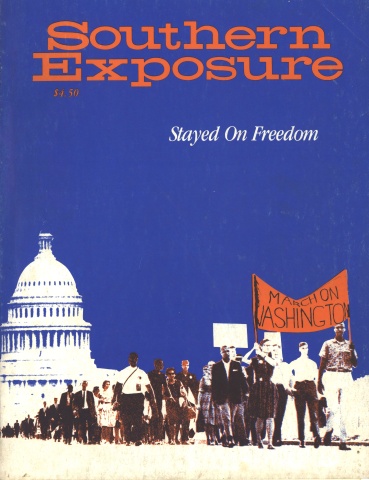

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

Tom Key had been drinking again, but that wasn’t strange. It was Saturday morning, and he’d caught a ride with one of his drinking buddies. Margaret Key figured that both men would be good and tight by the time they got back.

She wasn’t worried about her husband getting in any trouble. The 39-year-old black man would drink his liquor, but he wasn’t going to curse anybody or get into a fight. He’d just sit up in a juke joint and play cards or tell stories, and if trouble started he’d get on up and come on back home. Margaret was just angry that her husband was spending money drinking when he was too sick to get a job and too trifling to get on disability.

Margaret Key was sitting on her mother’s front porch when Russell Reid drove up with her husband and parked in the grass across the road. The wooden porch was filled up with her mother, her two nephews and her youngest son. The boys straddled the railing and stretched out on the old chairs, shouting and trading jokes. None of them paid much attention as Tom and Russell shared the last of a half-pint and talked quietly in the car.

Tom Key and Russell Reid weren’t sitting there long before a South Carolina Highway Patrol car pulled up behind them. In it was Gordon Paul, a white highway patrolman in his early twenties, heavily built and in excellent shape. The patrolman got out of his car, adjusted his belt and walked up to Russell Reid. “Uh-oh,” said one of the boys, grinning. “Russell going to jail now!” Everybody was paying attention.

The patrolman talked to Russell Reid for a moment, then walked around to the passenger side to talk to Tom Key. After a while, Tom Key opened the car door and the patrolman walked him back to the patrol car. Paul put Key in the back seat of the car, then walked back up to where Russell Reid was still sitting. The patrolman did not handcuff Tom Key. And he did not shut the back door.

Before the patrolman could reach Russell Reid, Tom Key had jumped out of the patrol car and run into the woods that stretched along the side of the highway. The patrolman turned and raced into the woods after Key. They were gone a long time. The boys strained their necks and laughed, wondering if old Tom had given the road patrolman the slip. Margaret and her mother smiled and shook their heads, trying to decide who was going to put up the money to get Tom Key out of jail.

When the two men finally came back out of the woods, Tom Key was walking in front of the patrolman. He was holding his side as if he were in pain, and he stumbled as he tried to walk. The patrolman pushed him once in the back, and then again.

As the patrolman pushed him the second time, Tom Key tripped and fell in the muddy grass at the edge of the highway. Gordon Paul stumbled over him and fell on his knees just to the side of the black man. Key scrambled and tried to get away again, but he was too full of liquor and too stiff to move fast. Before Tom Key could get fully to his feet, Gordon Paul pulled out his service revolver and shot him dead.

Across the road, Margaret Key screamed and collapsed on the porch.

It was May 3, 1975. South Carolina’s Bloody Summer of ’75 had begun.

By the spring of 1975, the rulers of South Carolina had good reason to believe that the days of the Movement were over in their state. After a long and bitter struggle, Jim Crow segregation had finally ended. Black people were moving into the mainstream in all areas of South Carolina life. The marches, boycotts and demonstrations of the ’60s were fading into memory. Black leaders throughout the state seemed more interested in consolidating their gains than they were in continuing the confrontations of the past. Integration had been painful for South Carolina’s white ruling class, but they had come through it and were still in control. In the words of the old Uncle Remus song, everything about race relations in South Carolina seemed “satisfactual.”

But the black workers of South Carolina were not satisfied. The right to vote and the right to eat at lunch counters were great goals in 1963, but after enjoying them for a few years black people found that they were not much to get excited over. The gains black workers had made in employment in the first few years of the ’70s were almost completely wiped out during the recession of ’74. White politicians had stopped complaining about the “lazy niggers” in their public speeches, but the same politicians who made those speeches in the ’60s were still in power in 1975. Most blacks did not trust them. There was a deep discontent against the white policemen who still patroled the black communities. Time and again, they showed that their real job was to “keep the common niggers in their place.”

While the black middle class enjoyed the gains they had made, the common black people of South Carolina watched the situation uneasily.

When a white person kills a black person in a small Southern community, anger and fear race through the black settlements like storm clouds rushing across a summer sky. Southern black communities have long memories, and many have seen the deaths of family members and friends go unpunished. The fear and anger is like a fever that snatches the community and shakes it. People reach for their pistols and shotguns, promising that they’ll “take one along” if they have to die. Ministers preach sermons, and congregations shout, “That’s right!” The conversation is in every juke joint and along every highway. The black community turns its angry gaze towards the white community, and each black person feels deep in the heart that “this time it has gone too far.”

South Carolina had seen several such isolated killings during the first half of the ’70s. The white rulers knew that it could be a dangerous situation, but they also knew what to do to contain it. If the white folks stayed cool, the anger would swell like a bubble gum full of air and then harmlessly burst. It would be tough going for a while, but they had the tools to isolate the anger to one community and keep it from spreading.

The morning after the murder of Tom Key in the quiet Lowcountry town of Moncks Corner, there was little to indicate that this situation would end up differently. But before the anger could blow over, a second black man was murdered. One week after the killing of Tom Key, a white Orangeburg County sheriffs deputy shot and killed a 19-year-old black youth named Emmanuel Fogle. Deputy Clark Ryder had been chasing Fogle only to investigate a possible stolen car. There were no other charges against the youth. When Emmanuel Fogle was killed, he was unarmed and trying to hide in the bottom of a 10-foot-deep ditch.

It was not finished. On May 31, Earl Miller was shot and killed by a white police officer in Conway. Miller was unarmed, and police had come to his house to settle a domestic dispute. On July 26, Herbie Morton was shot and killed by a white highway patrol officer in Greenwood. On October 19, Marvin Muldrow was shot and killed by a white city police officer in Florence. Both Miller and Morton were unarmed and had been stopped for traffic violations.

In each case, the police officers claimed self-defense.

The anger of the black communities swelled and exploded across the state. Each community saw a conspiracy to kill black men, and each community looked for the next murder to happen outside its door.

The established news media treated the killings as one long combined incident. An article in the November 10 issue of Newsweek read: “South Carolina’s blacks believe [there] is a systematic pattern of police brutality by white cops against blacks. . . . Though the incidents involved separate police forces and have no apparent connections, all six have occurred in roughly similar circumstances.” In August, the Associated Press said, “The killings of blacks by white law officers, and ensuing demonstrations, investigations, coroner’s inquests and murder trials have become a familiar sight in South Carolina this summer.”

The black-owned Charleston Chronicle called the killings “a declaration of war on the black community.”

In such a climate, black people across the state were ready to be mobilized and organized to deal with police violence. More so than any other organization, the South Carolina NAACP and its local branches seized the leadership of that struggle and set its tone and direction. But under NAACP leadership, so oriented to the black middle class, the Bloody Summer struggles suffered confusion, betrayal and finally death.

In four of the cities where the Bloody Summer killings took place, local NAACP chapters led the black response. While denouncing the killings in the most militant of terms, they channeled black activity into nonviolent demonstrations. All actions were geared towards forcing local authorities to bring the individual police officer accused of wrongdoing to trial. And when each one of the four police officers was cleared by the courts, the NAACP activity either stopped immediately or slowly wound down to nothing.

One example of this failed strategy was in the city of Florence. Several days following the killing of Marvin Muldrow by the city police officer, a huge number of black people gathered in a local church under the sponsorship of the Florence NAACP. During the meeting, black youths smashed the windows of a carload of whites who rode by the church shouting “niggers!” Within a few minutes, some of the black youths moved down the street and broke out windows in several white businesses near the church. Only a small number of youths participated, and city police quickly moved in to disperse the crowd and stop the violence.

But James Edwards, the Republican governor of South Carolina, felt he had to show his constituency that he was not giving in to the black community. Edwards ordered the National Guard into Florence on standby alert. The morning after the church meeting, Florence city police began a military occupation of black neighborhoods. Checkpoints were set up in various strategic areas. Black people riding or walking through the area were routinely stopped, searched and checked for identification. Helicopters patroled the skies over the black district. All this was done in the name of “preventing violence.”

Instead of denouncing this reaction from the state and the police, NAACP officials praised it. NAACP state field director Isaac Williams said that he was “awed and fascinated by the fact that law enforcement in Florence has the flexibility ... to use more than maximum restraint.” And when the NAACP sponsored a march in downtown Florence the following weekend to protest the Muldrow killing, Florence NAACP president Frank Gilbert publicly promised marchers that the Florence police would be present to protect them from “the more militant black factions.”

NAACP officials argued that they took such positions to prevent any possible rioting, but it was clear that they were more interested in stopping any activity which was not under their direct control and which did not follow their strict policy of taking the struggle through the court system. Similarly, when black students boycotted South Florence High School as a protest against the Muldrow killing, Gilbert condemned it. “We want the students to understand that we [the NAACP] want to keep this out of the schools,” he said in a statement to local reporters. “We want the educational process to continue.”

NAACP leadership also prevailed in Orangeburg, Conway and Greenwood. But in Moncks Corner, the scene of the first Bloody Summer murder, the situation was much different. In Moncks Corner, the Bloody Summer struggle was led from the beginning by a small local group called the Black Star Organization. The BSO was a collection of black workers and community activists, several of whom had originally been members of the Moncks Corner branch of the NAACP. In fact, the organization formed in the spring of 1975 largely because the local NAACP failed to take any action about the murder of Tom Key.

As one of its first actions, the BSO demanded that highway patrolman Gordon Paul be removed from all law enforcement duties in the state of South Carolina. To enforce that demand, the BSO organized a black boycott of the major white businesses in the town of Moncks Corner. The boycott lasted until June of 1976, more than one year after the killing. To supplement the boycott, the organization held monthly protest marches through Moncks Corner’s downtown section. And each week, the BSO distributed thousands of leaflets and newsletters around the county to explain its positions, announce its activities and bring news of Bloody Summer actions from other parts of the state.

When state and local NAACP officials were asked to support the boycott, they refused. The national NAACP had only recently been sued by a group of white Mississippi business owners over an NAACP-sponsored boycott, and South Carolina officials were afraid the same thing might happen to them. The suit demanded $2 million in damages for the lost business caused by what the local white businessmen called a restraint of their free trade. Such a suit reflected both the threat well-organized pressure posed for the white power structure and the vulnerability of a national civil-rights organization with a substantial treasury to a legal attack. With little money to lose even if their group was sued, BSO members argued that they did not see the need for an organization that was afraid to take action to protect the lives of black citizens.

If the NAACP had endorsed the boycott, local black church leaders would have joined and urged their congregations to support it. BSO members estimated that with active church assistance they could have kept 90 percent of the black community out of the white stores, and they could have quickly brought town officials to their knees. When the NAACP refused to endorse this boycott, timid church leaders had an easy out. But even without this critical support, the BSO boycott was 50 percent successful for almost the entire year.

In none of the Bloody Summer cities were the black communities able to get the accused police officers permanently removed. But Gordon Paul of Moncks Corner was the only officer to be kept off active duty for any great length of time. While officers in Orangeburg, Conway, Greenwood and Florence were put back out on the streets within a few weeks after the killings, Gordon Paul remained at a desk job for nine months following the death of Tom Key. Gordon Paul was also the only officer who was never brought to trial for the Bloody Summer killings. Since Inis court trial seemed destined to vindicate his action, the BSO never made prosecution of Paul a central demand.

The BSO said that its partial victory came because of three major differences with the NAACP strategy. While the BSO was not afraid to take militant actions designed to hurt local white businesses, the NAACP tried to accommodate itself to the white rulers. NAACP action ended with the courtroom acquittals, while the BSO said from the beginning that it had no faith that justice could be achieved in the courts. And while the NAACP consistently showed its contempt for and fear of the masses, the BSO regularly explained its positions to the black community through meetings arid leaflets and argued that the political education of black people was one major goal of the struggle.

While the BSO and the NAACP were arguing over strategies, South Carolina’s white power structure busily mounted a counterattack to (1) make it appear the police and not the black community was under attack; and (2) make sure that black anger was channeled into safe areas. For the most part, they were successful in both areas.

After he was continuously asked about police attacks on unarmed black citizens, the chief of the South Carolina Highway Patrol told a Newsweek reporter in November that the shootings would not have happened if blacks would stop “going out at three a.m., raping and violating the law.” Noting that 15 police officers had been killed by black people in the state in recent years (and he emphasized the fact that this had been done by black people), Governor Edwards said, “We cannot let law enforcement elements be held at bay by criminals in South Carolina.” The State newspaper in Columbia accused the NAACP of “racism” for protesting the killings, and said that the organization “shows 102 signs of becoming more the troublemaker than the peacemaker.” The Columbia Record also criticized the NAACP, calling it “a bad business — this harping on color differentials in the area of law enforcement.”

In an attack on the Black Star Organization, The Berkeley Democrat newspaper said, “We see no reason that any pressure group should be allowed to force the denial of [Gordon Paul’s] right to pursue the vocation of his choice.”

In a July editorial, The Charleston Evening Post gave a clear and ominous warning to all black South Carolinians: “Policemen, like everyone else, are human and make mistakes. Good citizenship as well as common sense tells us they should be respected and obeyed, especially in a tense situation. Some citizens would be alive today if they had heeded this cautionary counsel.”

Local observers saw the hand of the white rulers in changes made by the NAACP in dealing with the killings. During a statewide NAACP meeting in June, held just after the first three killings took place, a local delegate suggested that the organization set up a statewide task force to study police brutality in South Carolina. In the heat of the early black anger against the killings, the motion passed. In August, NAACP leaders held a well-publicized meeting with Governor Edwards to discuss the tense situation around the state. During the meeting, the leaders suggested that the governor set up biracial citizens committees to study whether law enforcement officers in the state were racially biased.

Critical differences emerged between the original proposal adopted by the NAACP in June and the proposal presented to the governor in August. The panel would now be chosen by a conservative Republican governor, rather than by the NAACP itself. It would be biracial, something which was not specifically spelled out in the original proposal. And rather than specifically studying police brutality and the Bloody Summer killings, it would now be spread along the more general topic of racial bias.

The governor agreed to appoint the committee.

Responsibility for gathering the information for the new Governor’s Committee on Police-Community Relations was given to the state Human Affairs Commission, headed by Jim Clyburn, a black politician. He revealed his position on the real cause of the disturbances in August when he announced in a speech that South Carolina police had an “image problem.” “Unless we can change the people’s attitude toward the police, we are not going to do anything about the problem. . . . Police need a good public relations program.” The governor echoed his comments and said he was shocked to learn that black South Carolinians did not have faith in the justice system. “Our system of justice works,” the governor declared, “and we are going to have to sell this.”

The Human Affairs Commission did not complete its study until April of 1976, and the Governor’s Committee finally issued its report in September. By then, the fires of the Bloody Summer protests had cooled. And instead of dealing with the original NAACP proposal to study police brutality, the committee’s report focused on how police could respond to the problem of its “bad image” in the black community.

Sometime during the fall of 1975, the NAACP came up with a plan to revive its political standing in the black community. NAACP leaders had been under attack for several months — from the press and white power structure for being too militant and irresponsible and from the BSO and others for selling out. The NAACP strategy in each of the Bloody Summer cities had been to hold one big march to help the community “blow off steam.” It was only natural that the NAACP would decide to have one big statewide march for the same purpose.

The January 15 march on the state capitol was originally set up to make two major demands. The first demand was for the state legislature to make Martin Luther King’s birthday a state holiday. The second demand was for law enforcement officials to stop the Bloody Summer killings. A broad coalition of religious, civic and community organizations was brought in to help organize and support the march.

NAACP officials felt they had good reason to bring the King birthday demand into the Bloody Summer protests. They argued that more people would turn out if the King birthday demand was included. This was questionable, since local NAACP chapters had organized local marches of as many as 3,000 people during the summer protests. The real reason, however, was that the NAACP felt more middle-class black people would respond to a march to celebrate King’s birthday. These people were needed to counter the possibility that black workers and community activists might respond to the rhetoric of black radicals scheduled to be speakers and turn the march into a militant rally.

The second reason the King birthday demand was included was that NAACP officials needed a victory. State officials had made it clear that they were going to protect their police officers at all cost, regardless of the charges against them. NAACP leaders thought there was a chance that the state would give them an out by granting the King holiday. A victory on the King birthday would turn NAACP leaders into statewide heroes and would cloud the fact that they had made no progress on preventing the Bloody Summer killings.

The January 15 march was a huge success in terms of numbers. Some 10,000 black people (and a handful of whites) marched five miles through downtown Columbia, then listened to speakers on the steps of the state capitol for over two hours. Government and black leaders alike called it “the largest civil-rights demonstration in the history of the state.”

It was also probably one of the least effective in South Carolina history. The state legislature refused to grant a state holiday for Martin Luther King’s birthday. And while 10,000 people stood in chilly weather listening to speeches condemning police brutality, the House of Representatives adopted a resolution praising the 29 law enforcement officers killed in the state in the line of duty during the previous decade. The resolution said that most South Carolinians believed that the police try to enforce laws “in an equitable and judicious manner for the good of all.”

Even in the midst of the march, the betrayal of the black community continued unchecked. Black state legislators knew that the legislature had rejected the march demands even before the speeches began on the capitol steps, but they never relayed this information to the crowd outside. Most marchers did not learn about the rejection until they heard it on their car radios on the way home or read about it in the paper the next morning.

The failure of the January 15 march began when the demand for the King birthday holiday was included. The birthday demand became the main theme for the march, and the media and many middle-class leaders eagerly downplayed the police issue. Of the 22 persons who spoke on the capitol steps that day, only three talked about the problem of the police. Key organizers of the march seemed satisfied that it took place and uninterested in following it up. For several years afterward, NAACP officials and black politicians used the march as a threat to hold over the state. But neither group ever officially informed the black community on the results of the march, nor organized a response to the rejection of the march’s demands.

The failure to build on the Bloody Summer movement was a blow for the unified statewide struggle in South Carolina. After the Columbia march, the movement shifted to local concerns. Black organizations concentrated on electing blacks or “sympathetic whites” to office. Black workers formed the backbone of a struggling trade union movement in the state. But these were mostly local efforts, and there were no attempts to link them up again in a statewide movement.

The common black folk of South Carolina showed their willingness to struggle during the Bloody Summer of ’75. The Black Star Organization and others showed some of the strategies and tactics that could be used to attack the white rulers and win demands. But under the limited vision of the middle-class leadership that dominated the South Carolina black community, people experienced betrayal and confusion, and the Bloody Summer movement was defeated. But deep in the shadows of the South Carolina plantations, the road to freedom was still open for those who dared to walk it.

Tags

Jesse Taylor

Jesse Taylor has been a South Carolina freedom fighter for many years. He is currently a staff member for Palmetto Legal Services. (1981)