This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

While many of us weighed the merits (or lack of them) of the various candidates in the November, 1980, elections, black voters in Pickens County, Alabama, faced a different dilemma than whom to vote for. For them it was a choice of whether to vote at all. It wasn’t a question of apathy - it was a problem of safety and security.

A pattern of outright resistance to the demands of black voters has emerged in this small southwest Alabama county. Voting Rights Act or not, black citizens in Pickens County find themselves subjected to threats, harassment and jail sentences if they challenge the all-white power structure. The intimidation and prosecution seems especially directed against those who register blacks to vote or who show others how to use the absentee ballot to increase black voting strength.

In the last two years, two black women and one black man have been convicted of charges ranging from voting fraud to disturbing the peace (at a polling place). Their stories follow a general description of the political atmosphere in the county by Geraldine Sawyer.

Geraldine Sawyer

Geraldine Sawyer grew up in Pickens County. After graduating from high school there in 1967, she went to Flint, Michigan, where she became involved in community organizing. She came back in 1976 to help her mother care for an aging aunt and is now mayor of the small unincorporated residential community of McMullen just outside Aliceville.

The only way we can survive is by voting. I started trying to be a deputy registrar because I knew blacks and some whites, when you say courthouse, they freeze up, they been scared off. If I were a deputy registrar, I could meet you on the street and say, here’s your card, fill out this application, and when the time comes to vote, you can vote. Rather than trying to get up gas money, picking up all these people and taking them there. But they said, “We don’t need any deputy registrars. We can’t pay.” I said, “I don’t want pay. I’m doing it for free. I got six other people that’s going to do it for free. The Pickens County Commission doesn’t have to pay us one cent.” But we couldn’t get it approved, we never got it.

So we went door-to-door, getting people to the courthouse and getting them registered to vote. I walked all summer, each project, every area. You know, that’s time-consuming when you’re talking to people that don’t understand. We got over 800 people registered this year, working out of small areas — Pickensville, Gordo, Reform. These are some of the areas that have been whitewashed all the time, that whatever “Mr. Whiteman” says goes. You don’t run, you don’t put black people to run for city council or county commission or any kind of board.

Not only that, but the police are a problem. We’ve had a number of deaths with no explanation. Last year, a guy was coming down the highway from Carrollton, the police were chasing him, and he goes off on the left side of the street rather than going off on the right. Then the car is all bent up, and then you see gunshot holes all through the car. Now, that’s never been explained. They bring them to a funeral home and pronounce them dead, and they don’t even have a doctor.

It’s bad for blacks not to be able to speak out, or say I’m filing a suit. We got a black guy here now that filed a lawsuit against one of the stores in downtown Aliceville. Then he and another black guy got into it at the pool hall. The other guy decided he’d drop the charges, but the state decided to go on and prosecute. That’s the way they get you, see. They sent a guy up for 25 years just last week, said he was a peeping tom. And just going on hearsay.

The first year I came back from Michigan, I applied to one of the banks, but my face was black. I was trained as a teller, but I didn’t get the job. Even at the police station, I was trained in that job, too. All you do is type the card, the color of your hair, your height, how much you weigh and what kind of incident you were involved in, and then you file it. I went for that job. But my face was too black. And I was qualified for it.

It’s not what you know, it’s who you know here. If you know somebody’s daughter’s grandfather, and he can talk to Mr. Whitey and say, “This person, they’re all right. They eat cheese, and no matter what you do, they don’t open their mouth,” then you’re hired because you’re good black folks. That’s the way it is. And we sit and talk about it. We just need a great big change.

We had a march in November of last year. You know what the white man told Willie Davis? He said, “You know, that was ridiculous you got up and stood on the steps and said what you said. You have a brother that’s in a little trouble. If you hadn’t said what you said, things would be better 96 Voter registration form used in Mississippi. for him.”

I sat in on Mrs. Bozeman’s trial, and it was the worst chopped-up, botched-up trial I ever saw in all my days. They took the older people that we were going around to, explaining what the absentee ballot was about. What they did, they took these old, old people that didn’t really understand, they took them in a private room with no tape recorder, and had them say, yes, they give us this, they signed this for us. You’re in there, you’re being badgered, you’re liable to say anything to make them leave you alone. And then they get the people on the stand. “Didn’t you say such-and- such on such-and-such a day in my office?” “Well, yes, I said that.”

Maggie Bozeman

Maggie Bozeman is a lifelong resident of Pickens County. She taught in the public school system there for 27 years until the summer of 1979, when she was fired after being convicted of voting fraud by an all-white jury.

Mrs. Wilder is the chairperson for the Voters League here in Pickens County, and I am the coordinator. We were involved in voter registration. We had a big campaign going in 1978. The goal was getting people registered and encouraging them to get out to vote.

The second big thing was conducting workshops trying to teach people the importance of getting to the polls, and their rights after they got there. On September 13, 1978, the Attorney General sent out an opinion on the voting procedure for helping the illiterate. We used this opinion in the workshops, stressing to people not to be ashamed, but to be aware that there were people available to assist those who did not understand the ballot. The third thing was, we encouraged them to get absentee ballots, if they were out of town or if they were sick.

In 1978, we had a young woman running for the Pickens County Board of Education by the name of Minnie Hill. She qualified against a Republican, an established banker in town.

The day before the election, that’s when I was picked up at school. Poor fool, I was just out there with my kids, as usual, having fun on the playground. I looked to the left of me and I saw the police, five cars. The kids and I said, “Somebody must have stolen something, what has happened?”

I got into the classroom with no fear, didn’t know anything. I had gotten in there, hot and all that, and over the PA the principal said, “Mrs. Bozeman, will you come to the office please?” I didn’t know what was going on. The sheriff was in the office. He said, “You’re under arrest.” I said, “For what?” He said, “You will have to go with me to Carrollton.”

There were three in the office just like I was a criminal or something. Three people in the office to pick me up. I said, “Well, I’ll get my bag. I don’t have to go with you. I’ll go on my own.”

The system tricked and convicted us. They said we sent applications for absentee ballots to people who were not aware. The application specifically spells out: where do you want your ballot mailed? You see, if my mother can’t read and write, and I am the daughter, she wouldn’t know the ballot when it got to her house, so I would have it come to my box. You have a right to have that ballot go to anybody’s house you want it sent to. We taught in the workshops that the person voting must understand the ballot, what they are voting on, and mark their own ballot.

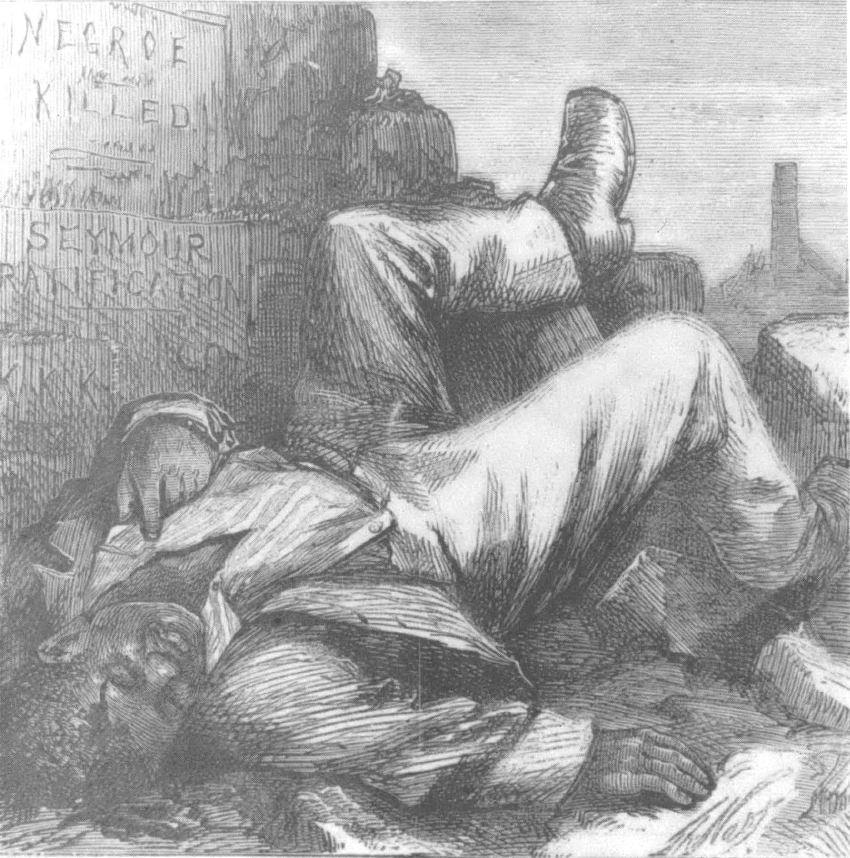

I never did get notice for the trial. One of the witnesses called me the night before around 11 o’clock. The day after I was convicted, the Pickens White tenor in the nineteenth century ended voting rights for most blacks. County Board of Education met in a special session at seven o’clock. The superintendent called me and told me not to report to class anymore. I said, “With this short notice, you mean to tell me I’m not supposed to go back to school?”

“Yes, ma’am! I am sending you a registered letter in the morning,” he said. “You just stay there until you get the letter, and you will not report back to school until further notice.” I haven’t worked since then. It’s rough.

I got four years, and Mrs. Wilder got five. The woman that ran for the Board of Education was indicted with the same charges, but they dropped hers at the end of my trial. She lost that race. If she had won, they would have prosecuted her sure as the world.

Here in the July, 1980, election, we had the opinion saying a voter could ask a person of their choosing to go in the voting booth and help them. If they would select you, say, “Would you please come here and assist me,” under the law, you have the right to do that. But they came up with an old law where it said the only way you could assist a person is if the inspector came and got you. It was mass confusion down there at the polls. There were many persons who never could vote on July 8.

We challenged that right away, and we were thrown out of the courthouse that day. Well, I wouldn’t stay thrown out. The policeman came in and said, “If you don’t get out, we are going to throw you out.” So we had to call the Justice Department. Some changes were made by the federal observers being here. Before the federal observers, you walked into the polling places here in Pickens County, and it was like walking into a church. Everybody saw you vote, everybody was looking at you to see what you were going to do. Now they have it blocked off, curtains are there where you go on the inside.

This year, October of 1980,1 went up to pick up some applications for absentee ballots, and the sheriff told me, “You’re getting some more of them. Maggie Bozeman will get them to vote if she has to vote them in herself. We’re going to get you this time.” An elected official said that.

This election — the presidential election, November 4 — we ran into all kinds of problems. I was told to get out at that election because I was assisting a person. And in Reform, Willie Davis was arrested because he was assisting a person.

You see, Davis is from Reform, Alabama, where the voting strength is four-to-one white. So we had some workshops again, and we stressed that in that area we need some black voting strength because we don’t have a voice to cry with. We got a small grant from the NAACP, and they formed a committee to sponsor a voter registration drive this past summer. And just prior to the November election, Willie Davis got 105 people registered from one Monday to the next Monday. Look what happened to him. Got arrested in the polling place, and one of the officials said, “All these niggers wouldn’t be here if it wasn’t for that Willie Davis.” I mean, the guy who got the folks registered, they got him. It’s obvious.

It’s a struggle here, just a struggle. Sometimes I just wonder how we’re going to survive, if it’s not any better yet. There was one white person on the day of my conviction that said, “It's a living shame.” One.

Willie Davis

Willie Davis grew up in Reform, Alabama, and graduated in 1978 from Alabama State University with a degree in education. He has been unable to find work in Pickens County, where there is a great need for good teachers. He is president of Pickens County SCLC.

Around four o’clock on Tuesday — election day — I returned to Reform and met two young ladies and gave them a sample ballot. They knew what candidates they wanted to vote for, but didn’t understand the amendments. The police came up and told me I had already voted and could not remain in the polls. I told the police I was there to help. They told me to stand back 30 feet. I kept asking them questions, then they just carried me, one on the left and one on the right, out of the polls. One hollered at me and I hollered back. The other one handcuffed me.

They took me to Carrollton, and the sheriff told the deputy to get on the phone and call Pep Johnson [the district attorney]. They carried me back in another little room. I asked how long they were going to keep me, and what they were charging me with. They said Pep Johnson had to make the decision on whether to lock me up and what charges to place. Pep Johnson called then, and they charged me 98 courtesy SCLC Albany, Ga., voter registration clinic, 1962. with disorderly conduct.

I’ve had a lot of messages since then from the police through people who run with me, my family and friends, saying they shouldn’t run with me. And they tell people to stay away from Maggie Bozeman and Julia Wilder. So I make it my business to be seen with them.

Julia Wilder

Julia Wilder grew up in Olney, Alabama, eight miles from Aliceville. She became active during the Civil Rights Movement in 1968, and has been the chairperson of the Voters League of Pickens County for many years. Along with Maggie Bozeman, she was convicted of voting fraud during the summer of 1979.

’Sixty-eight was my waking-up period. We’ve got a Piggly-Wiggly store here. The owner had five cashiers and no black cashiers. So we had a demand for some black cashiers. We had this march the last part of ’68. He had the police around, and 13 of us went to jail. I was in that bunch. I was the oldest person there.

We stayed in jail from Saturday night until Monday afternoon. But they got tired of us, I’m honest about it, because we were very noisy. We sang all night and slept all day.

So after then, he didn’t hire anybody right off, but we were boycotting the place, and he had to throw away so much stuff until he did hire some blacks.

In ’69, we got 200 folks registered within three months time, right here in Aliceville, and more in Ethelsville, and also Carrollton and Gordo. We did well with it. Been doing pretty well since, but that’s the most success I’ve had.

I didn’t know anything about absentees and such things other than what the probate judge told me about, the circuit clerk and the sheriff of Pickens County. I said it on the witness stand. I told them I remember that they didn’t challenge a single ballot when they were running it. That might be how come I got five years, I don’t know. I told them I was going to remember them when it came election time, and the same type of influence that I used to help to get them in there, I’m going to use to get them out. I told them there that I wasn’t going to quit, because I felt like what I was doing was right, and I was going to keep doing it. I didn’t do anything but ask people if they wanted to vote.

No matter how rough it gets, I’m going to be here, because I don’t have anyplace else to go. They used to put up signs saying, “Enough is enough,” and I go along with that, because enough is enough. But I went a little further and said, “Too much stinks.” And I’m still saying it.

On December 10, 1980, Willie Davis was convicted in Pickens County Courthouse of disturbing the peace. He was sentenced to 30 days in jail or a $500 fine. Davis’ case is being appealed to a circuit court jury trial. The convictions of Maggie Bozeman and Julia Wilder have now been appealed on the grounds of insufficient evidence to the Alabama Court of Appeals in Montgomery.

Tags

Judy Hand

Judy Hand is the projects coordinator for the Southern Organizing Committee for Economic Justice. (1981)

Scott Douglas

Scott Douglas is a writer in Birmingham, Alabama. (1981)