Freedom Rides

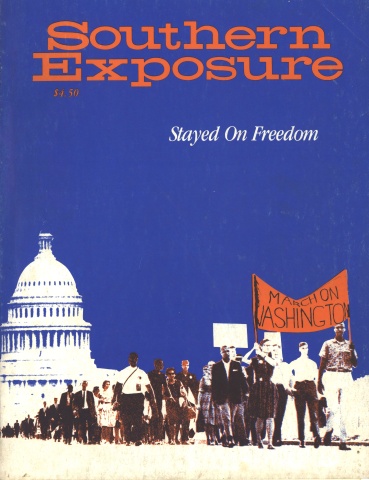

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

In May of 1961, one of the legends of the Movement began - a journey of blacks and whites together riding south from Washington, DC, to integrate Greyhound and Trailways buses and terminals. The Freedom Ride was organized by the Congress of Racial Equality. Anne Braden, writing a few years later, described what happened:

“The ride was relatively uneventful until it reached Alabama. Then a bus was burned in Anniston and the riders were attacked by mobs there and in Birmingham; and yet another phase of the Southern struggle was underway.

“The original riders, many beaten and bloody, abandoned the ride at Birmingham, but the Nashville student group picked it up and rode a bus on to Montgomery, where they were beaten by a mob; from there riders proceeded on to Jackson, Mississippi, where they were quietly and efficiently arrested. Throughout that summer Freedom Riders continued to roll south - all of them destined for the jails of Jackson and Mississippi’s Parchman State Prison. By the end of August, more than 300 had come, three-fourths from the North, about half students, and over half of them white.”

Crucial to the Freedom Rides was James Farmer, who had advocated and practiced nonviolent action for civil rights since the early 1940s, as one of the founders of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Farmer’s recollections are edited from a speech given at a conference on “Civil Rights: The Unfinished Revolution,” held at the Kennedy Library in Boston in 1980.

James Farmer

After the Irene Morgan case, in which the Supreme Court had ruled that segregated seating on buses used by interstate passengers is unconstitutional, nothing happened. The law was not enforced. The Supreme Court decision remained a scrap of paper. Then there was another decision in 1960, the Boyington case, in which the court ruled that segregation in the use of bus terminal facilities by interstate passengers is unconstitutional. But still nothing happened. It was a scrap of paper.

Letters poured across my desk at CORE from individuals complaining that they had tried to sit in the front of the bus or use the bus terminal facilities in the Deep South and were jailed or beaten or both. So what we decided to do was to force the federal government’s hand. The government was not going to enforce the Supreme Court ruling unless it became politically dangerous for the law not to be enforced.

Before the Freedom Rides, we wrote to the president, the vice president, the attorney general, the Department of Justice, the FBI, the Interstate Commerce Commission, Greyhound and Trailways corporations, and told them precisely what we were going to do. On May 1, we were going to have a ride with whites and blacks, starting in Washington, going through the Deep South, violating the Southern laws of segregation but supporting the Supreme Court. I don’t know whether you’d call that civil disobedience - we were disobeying the laws of a region but obeying the laws of the federal government. And on that ride the whites would sit in the back of the bus and the blacks would sit in the front, and they would refuse to move when ordered to do so and would accept the consequences of their actions.

So we wrote to all the aforementioned persons. We got a reply from none of them. No reply at all. So we recruited 13 or so people and trained them in Washington, DC, for an intensive one-week training period. Most of them were young, but there were a couple of elderly people. The training consisted of having lawyers speak on what the legal situation was and what one’s legal rights were when arrested; having social scientists speak on what the customs and mores were and the extent to which the local communities would go to enforce those customs and traditions; having activists speak, and so forth. Then we engaged in role-playing, with some of the recruits playing the role of freedom riders sitting at a simulated lunch counter, others playing the role of hoodlums coming in to beat them up. By the time the week’s training was over, I felt that these people were ready for anything, including death. And they knew that death was a possibility.

We were hoping that, even though we’d received no letters, the FBI was going to protect us. That was a vain hope. We learned later that the FBI had gotten our itinerary, since we’d sent everything to them, all the letters, and they had passed on our itinerary to local police whom they knew to be active in the KKK. And for that reason, two of the freedom riders who were brutally beaten — Jim Peck and Walter Bergman — are now suing. Peck had 53 stitches taken in his head when he was left for dead in a pool of his own blood in the Birmingham bus station. Bergman was so brutally beaten around the head that he had a stroke; he has been confined to a wheel chair ever since. And others were brutally beaten. One fellow had his back broken; fortunately, he was not paralyzed somehow. Another had his nose broken. A bus was burned to the ground, the people almost incinerated. Still, no action. No reply to any of the letters.

Lucretia Collins

One of the Nashville students who continued the Freedom Ride from Birmingham to Jackson was Lucretia Collins. A few weeks later, she sat down with James Forman and recorded her recollections, which he included in his book The Making of Black Revolutionaries.

I was silent most of the way from Nashville to Birmingham. We had planned not to identify ourselves with one another because our purpose was to get to Birmingham and not be stopped on the way. Certainly we would have been stopped if we had identified ourselves. This was proven by Paul Brooks, who sat by Jim Zwerg. He should not have done this, for that identified them. Sure enough, they were arrested within the city limits of Birmingham. Black and white just do not ride together in Alabama.

We remained on the bus after they were arrested. A policeman got on at this point, supposedly to escort us to the bus station in downtown Birmingham. I went to get off, but I was blocked. And I was blocked for quite some time.

Later, the chief of police came and he told us we were in danger of our lives and that he was placing us in protective custody. At this point, the policemen got very rough with us. It was like a moment of rejoicing to them, as if they had really won something by getting us to go to jail.

We got into the wagon, pleasantly. We went to jail. We sang all the way. It was a rugged ride to that jail; I think they tried to turn us upside down in the patrol wagon because they were turning curves very sharply. And speeding. The patrol wagon caused quite a sensation as we were going through town. People were applauding. This gave us more determination.

In jail, I made as many friends as I could. There was a woman who had a severe speech defect and since that time, I have been reading about that kind of problem. This woman interested me in particular because the others made fun of her and mimicked her. This is very bad to me. I talked with her a long time.

The following night at 11:30 p.m., Bull Connor came into our cell and said that since we were from Nashville he was taking us in a car back to Nashville. We protested, but that did not do any good. I was pushed out of the cell and Katherine Burke, who refused to go, was carried out. The fellows were pushed and shoved out. During our ride to Ardmore, Tennessee, we made it very clear that we were not afraid of jail and that we were not afraid of being attacked on the road. The driver of our car said that he would kill his daughter before he would allow her to go to an integrated school.

When we got to the Tennessee state line at Ardmore, Bull Connor pointed to a train station and told us to catch a train from there. It was just breaking day. We saw a telephone booth on the corner and we called Diane. She asked what we were going to do and we said we would call her back. This was a gripping moment. We knew that anything could happen to us. We were alone with our luggage and everything in the middle of the street. We did not know if there had been attackers following the so-called police car or if attackers would come at us from somewhere in Tennessee. We were 93 miles from Nashville and 193 miles from Birmingham.

Two fellows decided to see if they could find a Negro home. The two scouts came back in 10 minutes and we knew that they had found something. So we took our bags and walked down the railroad tracks. The people let us in and we called Nashville again. Leo Lillard, who was coordinator of the Freedom Ride, said he would come right away.

We felt we had to go back to Birmingham because if we went home to Nashville it would be exactly what they wanted us to do. They had put us out in the middle of the night to frighten us. We would lose another fight if we did not return to Birmingham. We knew the dangers we faced, going on the highway with Tennessee license plates.

Leo arrived — he drove those 93 miles in 55 minutes. We planned our trip back to Birmingham so that we would not look so conspicuous. One fellow was on the floor. The other three were slumped down in the back so that it would not look crowded. Katherine and I sat in front with Leo and Bill. I pretended that Bill and I were sweethearts. And I lay on his shoulder. Katherine lay on Leo’s shoulder. In this way the car did not look so crowded.

Katherine was from Birmingham and she helped us find a way to bypass the city and get to Shuttlesworth’s house. Several kids from Nashville and two from Atlanta were waiting for us there. Diane, who represented Nashville on the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, “Snick,” had called other members, and we were happy to see Ruby Doris Smith, who had gone to jail in Rock Hill with Diane. There was this great, joyous reunion. We hardly had time to eat because we were so eager to get back to the bus station.

At the station, they wouldn’t let us on the bus. Some of the kids slept but I was determined not to go to sleep. I felt as if I had been without sleep for so long that it just didn’t matter. I did not want people watching to think that we were so weary, because to me that brings the morale down.

We patronized the little fountain in the bus station. We walked around. Some of the kids played the games that were in the station. We just made ourselves at home in the “white” waiting room. We went to the bathroom at will. Except the fellows; they did not go to the bathroom whenever they felt the need because there were a couple of men in the building who were subject to being very violent. And they would follow them into the bathroom.

During this time, we tried to catch every bus that left Birmingham. The bus drivers said they wouldn’t drive if we got on board. They kept refusing us.

It just seemed that all the blood was drained from you or something. And we began to sing. I don’t think that song — “We Shall Overcome” — ever had so much meaning as it did that morning. It was really felt that morning, after we had waited so long and been refused so much. Well, we had a little worship right there. A young man prayed. We read scripture. It was unlike any of the other devotional periods we had had. And I saw kids that I knew were not really dedicated before. At this point you could see it come out. I was just filled with mixed emotions.

The next bus, the next bus, we caught. It was a very strange thing - we stood there and we prayed and we sang. And it was so meaningful. And the next bus we caught. It was seven a.m.

On the ride from Birmingham to Montgomery, I was very relaxed. I dozed off. When I awoke in Montgomery, I felt something was wrong.

There was no mob, but I felt apprehensive. Then I looked around and saw no policemen whatsoever. We were the last people to get off the bus. The other Freedom Riders had walked down a little to the left on the platform. I saw Katherine and John Lewis being televised by NBC. At that point, this very nice man from Life was standing in front of eight people by the door. While Katherine and John were talking to the television man, I saw this Life reporter sort of spread his arms out as if to keep those eight people back. I think he must have felt something was wrong and he was really holding up the action that the crowd of eight wanted to take against us.

When we noticed that tills crowd was moving toward us, I think John Lewis said, “Let’s all stand together.” A man with a cigar began to beat the NBC cameraman. A crowd started to gather. We were ignored at first and I noticed that there were no cabs or cars to pick us up. The crowd knocked the cameraman down and he dropped his camera. One man took it and smashed it on the ground. He picked it up and threw it down again and it fell into many pieces. I saw the cameraman moving down the street. The mob was after him. Then some of them noticed us. Two cabs came by. The driver of one said that the best thing was for the girls to leave. There were five Negro girls and two white girls. Four of us jumped into the cab. The cabdriver, a Negro, said, “Well, I can’t carry but four.” He had a little boy with him. At this point someone pulled the fifth girl down in the cab. The two white girls were still standing outside. “Well, I sure can’t carry them,” he said. But there was another cab next to us so we told them, “Get in right away.” They went in the cab. Some white fellow opened the door and pulled the driver out. I don’t think they attacked him in any way, I’m not sure. But anyway, they pulled him out and prohibited him from driving the cab.

At this point, our driver decided to pull off. There were two exits. We went to the exit facing us. There was a crowd coming in this exit. We saw that either we would have to drive over the people or get out of the cab. So we decided it would be best to back up and try the other exit. At the other exit, we were blocked by cars. The driver was really frightened. He told us he was going to get out of his cab and leave us there.

Blocked in by the cars, we looked back. The mob had attacked the fellows. I saw Jim Zwerg being beaten brutally! Some men held him while white women clawed his face with their nails. And they held up their little children — children who couldn’t have been more than a couple of years old - to claw his face.

I had to turn my head because I just couldn’t watch it.

Finally, our driver, perhaps because we had calmed him down a bit, agreed to stay with the cab. Although we were nervous, frightened and did not know what to expect, we weren’t screaming.

We managed to drive out of the parking lot. Then the car began to give us a lot of trouble. We thought the best thing to do would be to find a Negro home. Any Negro home. This little boy in the cab saved the day. He helped us find a Negro home. The car broke down twice. After the second time it broke down, we managed to get to the Negro neighborhood in second gear.

When we got there, Katherine ran into the house. We got out and told the lady what happened. So they welcomed us. They were very warm. Katherine called Reverend Shuttlesworth in Birmingham and she told him 38 what had happened. Then she called some of the people whom he told us to contact in Montgomery. A very nice lady, who I think was a fighter for civil rights, lived around the block. She asked us to her house. We went and listened to the news reports. And of course the report was very biased.

After this, we went to another woman’s house for late breakfast. I think all of us found difficulty in trying to eat. We were still listening to the radio for the outcome of the violence. We heard that the mob had swelled. Other people were being attacked besides the Freedom Riders. Kennedy’s assistant, Siegenthaler, had been hurt and was suffering from a minor brain concussion. We ate. Somehow we managed to eat.

The next day, Sunday, we were to meet at the First Baptist Church. We found out that there were federal marshals in the city and we were being guarded. The city policemen watched us carefully as we moved from one destination to another. A mass meeting in our honor was scheduled for that night, with Martin Luther King as the main speaker. We managed to assemble and spent most of the day in the library of the First Baptist Church, wondering if they would arrest us there.

The time came for the mass meeting. We were introduced as the Freedom Riders. They gave us much applause. The people were very warm. There was an all-out welcome.

We were being televised by most of the networks, NBC, CBS, ABC. There was Associated Press, United Press International, and then the local reporters. Several speakers sat up on the platform: Martin Luther King, Jr., Reverend Shuttlesworth, Jim Farmer of CORE, Reverend Abernathy, Reverend Walker, Diane Nash and others. Reverend King was going to give the main address of the evening.

Before the address, we received word that a very large mob had assembled outside. Later, we got word that a group of blacks had assembled also. King, with several other ministers, went out and was successful in getting the group to disperse. Then one of the federal marshal’s cars was set on fire and the white mob began to stone the marshals.

The Negroes did disperse, I think, but the white mob remained. They began to throw tear gas canisters. The atmosphere in the church filled with this gaseous, suffocating smell. I couldn’t help but think how wonderfully Reverend Seay was directing the people. He told them not to panic, not to become hysterical in any way. The gas was choking many people, but they followed him beautifully. We were large in number, very large. The church was overcrowded and the tear gas made it difficult to breathe. People’s eyes began to run and they began wiping them.

We sang. We prayed. We were told not to open the windows. Many of these people had been in the Montgomery bus boycott and they knew from experience what it was for people to try to intimidate them. But the desire for freedom was so strong throughout the group that nothing, nothing the mob could do, would stop us in any way.

We learned that Governor Patterson had ordered out the National Guard. Soon the church was surrounded with National Guardsmen. The mob still had not dispersed completely. Then we were told that we were to remain in the church overnight for our protection, for our own protection.

Here we were, a group of peaceable people trying to assemble, to exercise a right which our Constitution guaranteed us.

We decided to make the most of the situation. We sang and the fellowship grew stronger and stronger, person to person to person. All the Freedom Riders had been without food all day. We had sent for sandwiches, but the mob had checked our possibility of getting them. People grew weary, some irritable. Still they managed to discipline themselves. About this time, King gave his main address. It gave even more encouragement.

Eventually, very early in the morning, most of the people were taken home in large Army trucks.

From Montgomery we went to Jackson. I was elected a spokeswoman. Most of the kids, wherever they came from, tended to put the students from Nashville on a pedestal almost. Perhaps it is because we had been very successful. We made no bones about it. We were so willing to give everything, including our lives.

There was a lot of tension on the ride to Jackson. We didn’t know what would happen when we got to the Mississippi line. Whether they were going to implement federal and Alabama state “protection” or turn us over to the Mississippi state police. We didn’t know.

They said they would arrest us. They did. They followed us, literally followed us, through the bus station and into the white waiting room. We were arrested and taken to the Jackson city jail. We went to trial. We were found guilty. Disturbing the peace, trespassing. That’s about it.

After my sentencing, I only stayed in jail for 30 hours. I had asked to be bailed out if we were arrested; I wanted to go to my graduation. Not to march down the aisle, but I thought my degree would not be conferred and I wanted to be there to see. I was going to march in the procession. I wanted them to pull me out of line if they were not going to give me my degree.

I later learned that the school had planned not to confer my degree on me. I also learned that our classmates had planned to walk out if they did not let me graduate. Perhaps because of this, I got the degree.

I want to go back to Jackson because I feel that I have left a job undone. I feel that sometimes one should stay in jail with no bail and sometimes one is more effective if he comes out of jail. I felt I would be more effective by accepting bail. But I feel incomplete. The Freedom Ride — I am willing to do it all over again because I know a new world is opening up. To me, the entire Movement is symbolic of the Fight for human dignity.

Farmer

Finally, when we reached Montgomery, Alabama, we got a wire from the attorney general asking us to halt the Rides and have a cooling-off period. Well, we discussed it, and the reply which the riders agreed upon was, “We’ve been cooling off for 300 years. If we cool off any more, we’re in a deep freeze. The Rides will go on.” We still had not created the crisis, though that burning bus was in headlines throughout the country, if not the world. It became the symbol of the Freedom Rides, the burning bus superimposed upon the photograph of the Statue of Liberty and the torch. The rides went on into Missisippi after a riot in Montgomery, a white riot where we were held in a church overnight under siege.

Bobby Kennedy acted then. He had been forced to act. This was headlined all over the world. He sent U.S. marshals, a large number of them, into Montgomery. He of course had gotten on the phone before then, called there and said “Get that bus moving.” No driver would drive the bus. He said, “Where’s Mr. Greyhound? Can’t he drive a bus?”

Now this was only because the pressure had been built up. We filled up the jails of Mississippi. First the local jails in Jackson, the county jails, and then they sent us all to the state penitentiary at Parchman. We filled up the maximum-security unit. Bobby Kennedy Finally acted, since he knew that we were not going to stop. On every bus that went into Jackson, Mississippi, there were more Freedom Riders. These were not only CORE, there were SNCC people, and there were other people unrelated to any organization, who were volunteering, saying, “Send me, I’ll go, send me, I’ll go,” even though they knew that it might be the end of their days.

So Bobby then acted. The strategy worked. He called upon the ICC to issue an executive order, to issue an order with teeth in it which he could enforce. And the order was issued that as of a certain date the “For Colored” and “For White” signs must come down on all the buses and in all terminals used by interstate passengers and must be replaced with signs saying “Racial segregation in the use of these facilities is unconstitutional,” and be signed by the attorney general and the head of the ICC. And we notified the attorney general that on the day after the effective date of this order, we were going to send test teams throughout the South, of white and black, not riding, not freedomriding, just testing the enforcement. And if they found that it was being enforced, great. If it were not being enforced, then the Freedom Rides would resume the following day. They were being enforced. But we felt that we had to keep that kind of pressure on them to get the action taken.