Freedom Schools

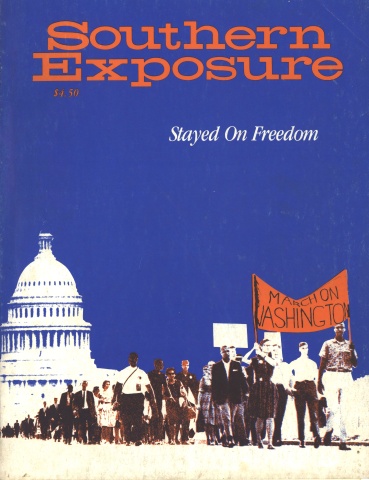

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

The murders in Neshoba County in June, 1964, of James Chaney, black, and Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman, both white, were intended to discourage others from joining the Summer Project; instead they helped to fuel the fires for an intense and diverse struggle for freedom. The Project went on, with some protection from the federal government brought on by the publicity surrounding the murders, to include far more than voter registration. Out of that summer came the Free Southern Theatre, which continues to provide inspiration today. A “White Folks” project grew out of the conviction that organizing Mississippi meant organizing in both white and black communities. The summer also gave rise to the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, which challenged the traditional Democratic Party of Mississippi at the 1964 Democratic National Convention. And the freedom schools, which originally fed into the voter registration drives, had a life of their own, as Len Holt describes in this essay from 1965.

Len Holt

Bluntly the teachers had been told that they had about eight weeks to develop those leaders needed and that there’d be no need to search for them; every morning when they said “hello,” the leadership potential would be standing there before them. The need was for revolutionary leaders, and attending the freedom schools was an act of defiance in Mississippi, a state where defiance, traditionally, is revolutionary.

The teachers-to-be had been told that most of their students would be from the “block,” the “outs” who were not part of the Negro middle class of Mississippi (which is composed primarily of teachers); and that 42 knowledge abounds in the Negro communities about the subtle forms of ignorance and subservience to the state of Mississippi inflicted in the regular public schools.

From a single-spaced, eight-page, legal-size document headed “Notes on Teaching in Mississippi,” the same theme had been pushed over and over again: “The purpose of the freedom schools is to help them begin to question.” This was the guideline asserted by Jane Stembridge (SNCC’s executive secretary in 1961), who also sought to answer for the teachers this question: what will the students demand of you?

The answer was this: “They will demand you be-honest. Honesty is an attitude toward life which is communicated by everything you do. Since you, too, will be in the learning situation — honesty means you will ask questions as well as answer them. It means that if you don’t know something, you will say so. It means that you will not ‘act’ a part in the attempt to compensate for all they’ve endured in Mississippi. You can’t compensate for that, and they don’t want you to try. It would not be real, and the greatest contribution that you can make to them is to be real.”

Charley Cobb was the mother-father of the idea of having freedom schools as part of the Mississippi Summer Project. Charley was a SNCC field secretary who had postponed for another year the pursuit of his own college career at Howard University, where his talents as a gifted creative writer were being polished. He present ed the idea of freedom schools to one of the early planning conferences of the Freedom Summer. With the characteristic calm and quiet persistence of those like him who have found internal security in their personal lives by giving them meaning and direction, Charley pushed the idea.

Mendy Julius Samstein, another SNCC field secretary, had contributed to the freedom-school notes by detailing some of the problems of freedom-school training. His suggestion had focused on the facts of facilities for the schools: they would all be scrounged, “and if you are white, you will almost certainly be the first white civil-rights workers to come to town to stay. You will need to deal with the problem of your novelty as well as with the educational challenge.”

The words had been given.

Frightened of life, death, the students, themselves, and every other matter that they could crowd into their concern in the short space allotted between their arrival and the beginning of the schools’ tensions, the teachers began their tasks.

It was a hot morning in early July when the freedom schools, the temple of questions, opened.

That date — July 7, 1964 — will be cursed by the power structure of Mississippi and celebrated by the lovers of human dignity as the point of the beginning of the end — the end and the downfall of the empire of Mississippi, the political subdivision, the state that exhibits best the worst found anywhere in America.

As the overly scrubbed, intensely alert and eager students poured into the churches, lodge halls, storefronts, sheds and open fields that served as school facilities, both teachers and students trembled with the excitement of one taking his first trip to the moon. From the beginning, the schools were a challenge to the insistent principle that everyone had talked about so much: flexibility.

Where the initial plans had been for only the tenth, eleventh and twelfth grades, one found sitting in the informal circles youngsters with the smooth black faces and wondering eyes of the impish ages of nine and 10 who were mere fifth-graders. Flexibility. And there just behind teen-age boys — with slender, cotton-picking muscles — were sets of gnarled hands and the care-chiseled faces of grandmothers, some of whom said they thought they were in the seventies (birth records for the old are almost nonexistent). Flexibility.

Where Tom Wahman and Staughton Lynd had thought that there would be only 20 or so schools to be planned for, 50 of them had sprouted before the end of the summer. Where a mere 1,000 students had been hoped for, 3,000 eventually came.

To meet all these changes and challenges, flexibility became the rigid rule. While those in charge of coordination and administration worked to resolve the logistical problems of swollen enrollments, the tasks of education proceeded in the first 23 schools to be opened, which were scattered throughout the state in 19 communities: Columbus, West Point, Holly Springs, Greenwood, Holmes County, Ruleville, Bolivar County, Greenville, Clarksdale, Vicksburg, Canton, Madison County, Carthage, Meridian, Hattiesburg, Pascagoula, Moss Point, Gulfport and Laurel.

Happily, the concern about the ability of the rural Negro communities to accept the white teachers readily was a wasted concern. After a day or so and a few touches of the white skin and blond tresses, the white teachers ceased to be “white” in a Mississippi sense. The first-name basis between students and teachers, the obvious sincerity, and the informality of the classroom situation all contributed to the breaking of any barriers that existed and enhanced the learning situation: if there were chairs, they were arranged in circles rather than rows; no one was required to participate in any classroom activity while in class; to go to the toilet or outhouse, one did not need to raise a hand to get permission; not disturbing others was the only consideration requested of the students.

And, most important of all, the teachers asked the students questions and the students talked; the students could and did say what they thought to be important, and no idea was ridiculed or forbidden — an immeasurably traumatic joy for the souls of young black folk.

The freedom schools were — and are — a collection of institutions to train leaders, and for that reason approximately half of the average of nine hours spent daily in school was utilitized in a direct approach to develop Mississippi leaders.

Serving as the basic teaching material for leadership was the Curriculum Guide for Freedom Schools, by Noel Day. Out of the need for training material for students attending classes in Boston churches and lodge halls during the boycotts against Boston’s token integration, Day had prepared a curriculum; with appropriate adaptation and revision, this Boston curriculum became the bible for leadership training in Mississippi. This curriculum, in mimeographed form, was divided into seven units:

• Comparison of the student’s reality with that of others (the way the students and the way others live).

• North to Freedom? (The Negro in the North.)

• Examining the apparent reality (the “better lives” that whites lead).

• Introducing the power structure.

• The poor Negro and the poor white.

• Material things versus soul things.

• The Movement.

Interwoven into Noel Day’s freedom-school curriculum were extensive reading and discussion of Negro history and hundreds of questions along the margins for the teachers to ask.

But there were problems. The freedom-school teachers — mostly Northerners themselves — on one hand were well equipped to describe the ghetto life of Northern Negroes; on the other hand these same teachers had stirred the alert and eager minds in the black bodies to challenge, to think and to question. These students knew well that this was a Summer Project, that come the fall the teachers would hop on the Illinois Central (freedom train) and ride in style across the Ohio River (the Red Sea) to the Promised Land.

In the learning situation the teachers did not coddle or protect the students from facts. For their own comfort, the teachers taught too well or the students learned too much. One student bore into the heart of his teacher: “I believe what you have been trying to say. This is our land. It’s worth staying and fighting for. I’m gonna be here when those leaves over yonder are gold. If you believe what you’re teaching, where should you be?”

The prison walls crumbled a little more.

The black giant was stirring.

Almost always there was the push of the students into fields where they could be creative. Where there was a mimeograph machine, weekly newspapers were written, typed and published by the students. Where there was a record player or some musical instrument to be played, assignments were given to describe the sounds in words and even to compose songs and words. Rorschach-like colors were splashed on large sheets of paper to be described from the students’ experiences. Class organization was encouraged, with presidents and sub-officers to carry out functions within the class and to teach the fundamentals of parliamentary procedures.

Poems were read, such as Langston Hughes’ “Blues”:

When the shoestrings break

On both of your shoes

And you ’re in a hurry –

That’s the blues.

To these poems and others by Frost, Gertrude Stein and e.e. cummings, the students were asked to respond by writing their own poems, which on some occasions created anguishing but vital opportunities for self-exploration. The class situation in Harmony, Mississippi, where Allen Gould, 20, of Detroit, Michigan, a student at Wayne State University, used this device, provides an example.

The Negroes of Harmony are a closely knit, fiercely proud group with an above-average number of persons in their midst who own small tracts of land, from which they eke out a living growing cotton and beef cattle. Some 12 miles away is Neshoba County.

Several students read their poems — one was about household chores; another told about the first time the poet had heard the word “freedom” — and for their originality and ideas the poems received the reward of applause from the class.

Then Ida Ruth Griffin, 13, unlike those before her, decided that she would stand and read her poem. The sun shone on her soft brown face, causing it to glisten. Her eyes sparkled with a deep fire as her voice came forth melodiously and with just a slight dramatic tinge; she read in a slow cadence:

I am Mississippi-fed,

I am Mississippi-bred,

Nothing but a poor, black boy.

I am a Mississippi slave,

I shall be buried in a Mississippi grave,

Nothing but a poor, dead boy.

The rustle of the leaves hushed and the blades of grass appeared to be straining to hear.

She finished.

There was silence, a silence that lingered. The eager young faces grew sullen and flushed with anger as if somehow a scab had been ripped from an old sore or Ida Ruth’s poetry had betrayed all that they were learning of denying the myths of Negro inferiority.

On the silence lingered until the floodgates of scorn poured forth from others in the class. In an angry chorus they responded with fierce refutations: “We’re not black slaves!”

The teacher, Gould, felt the compelling urge to speak in an effort to save this brown, beautiful and unknown young bard from more verbal attacks, but his tongue was stilled. All along the desire had been to encourage the students to think and to express those thoughts, and expressing opinions often includes speaking opinions other than what a teacher might think.

“She’s right,” spoke another student, a tall reedy girl with a sharp mind. “We certainly are. Can your poppa vote? Can mine? Can our folks eat anywhere they want to?”

Silence engulfed the class again momentarily, and then everyone began a cacophony of talking and thinking aloud, scattering ideas.

Gould’s chest filled with the joy of seeing the sun rising in alert minds that were heretofore damned by the oppression of conformity.

The black giant had stirred some more.

Tags

Len Holt

Len Holt is a Movement lawyer who wrote this article in 1963 while he was a National Lawyers Guild observer of the Southern Freedom Movement. (1981)