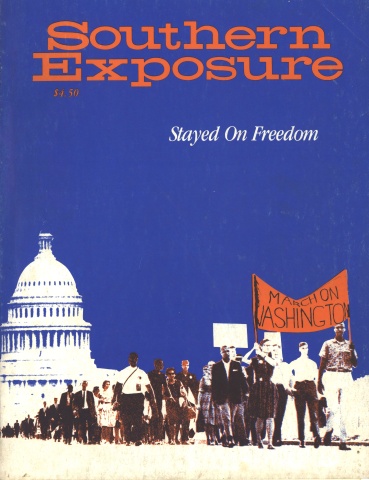

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 1, "Stayed on Freedom." Find more from that issue here.

The historic 1964 Freedom Summer brought 1,000 young people from across the nation to Mississippi to work in the Civil Rights Movement. During that summer, I never set foot in the state of Mississippi.

This was not because I was not active in the Civil Rights Movement. I was working all through the South, and had been in and out of Mississippi many times. But I stayed away that summer at the request of good friends in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the main mover in Mississippi. It was a friendly request: “Help us by staying away,” they said, and I did.

This illustrates an aspect of the Freedom Movement of the ’50s and ’60s so far almost totally ignored by historians: the war that was waged to keep anyone suspected of being “radical,” and thereby any radical ideas, out. It was a war initiated from the highest levels in this country, with assistance from within the movement itself.

Thus there was a category of people who lived and worked on what I call “the fringes of the Movement,” never quite accepted and sometimes viewed as more dangerous than the segregationists. In my own case, the problem was in part my connection with the organization I worked for, the Southern Conference Educational Fund (SCEF), and in part my own history and that of my husband and coworker, Carl Braden.

Carl was a journalist who had a long history in CIO labor organizing drives. From the late ’40s on, we were active in militant civil-rights activities in Louisville, Kentucky, where we lived, and in 1954 were charged with sedition after we (being white) bought and resold a house in a segregated neighborhood to a black couple. It was a flamboyant case, which we finally won, but in the process we became symbols of evil to many people.

We went to work in 1957 as field organizers for SCEF, which did nothing to allay the fears of people who already saw that organization as a red menace. SCEF descended from the Southern Conference for Human Welfare (SCHW), which had been organized in 1938 to attack economic problems in the poverty-stricken South, and which quickly became a civil-rights organization also, because it could not deal with economic issues without confronting segregation. It was a coalition — of church people, unionists, students and Communists, which in 1938 did not seem unusual. Its program could only be described as reformist: support for Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal programs, labor’s right to organize, an end to racial discrimination.

Its label as a “red menace” came from attacks by various governmental investigating committees that roamed the land calling efforts for social change subversive. SCHW was a first major target of the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), also organized in 1938, under Representative Martin Dies of Texas.

HUAC issued a report saying SCHW was not interested in “human welfare” at all but was promoting communism in the South. That report became the basis for all future attacks on SCEF, and was used by Senator James Eastland and his Internal Security Subcommittee at 1954 hearings in New Orleans to prove that SCEF was also “subversive.” About that time, many Southern states began setting up committees modeled after HUAC (LUAC in Louisiana, FUAC in Florida, etc.), and they all began to scratch each other’s backs, each quoting reports of the others to prove that SCEF and all who worked with it were a menace.

SCEF was not the only group attacked this way. The National Lawyers Guild, also dating back to the ’30s, was another — especially when it began sending lawyers into Mississippi, where the freedom movement could find virtually no local lawyers. Len Holt, a militant young black lawyer in Norfolk who played a key role in bringing the Lawyers Guild south, was under constant assault; at one point, agents of the Virginia investigating committee burst into his office and demanded all his records. According to Jim Forman, SNCC executive secretary, Mississippi Movement leaders were once summoned to a meeting at the U.S. Justice Department, where Arthur Schlesinger, Jr., told them he and others found it “unpardonable” that SNCC would work with the Lawyers Guild.

Another target was Highlander Folk School in Monteagle, Tennessee, a training center for labor and civil-rights organizers since the ’30s. In the mid-’50s, Arkansas Attorney General Bruce Bennett, whose mission was to save the South from both integration and communism, came to Tennessee to inform that state’s legislators that Highlander was harboring a nest of subversives, and they’d best investigate. They did, with great fanfare. (For more details on the attack on Highlander, see Southern Exposure, Vol. VI, No. 1, Spring, 1978.)

Probably the most high-powered attack of all was aimed at Jack O’Dell, staff member of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and one of the best organizers and fundraisers that organization had. He had been called before HUAC in Atlanta in 1958. It was John Kennedy himself who took Martin Luther King, Jr., aside during a White House conference and told him SCLC had to get rid of O’Dell.

The interesting thing is that none of these people or groups that were targets of these attacks were advocating anything very radical. We were supporting the goals of the Freedom Movement, and that’s all. SCEF, for example, had a single-point program: the ending of segregation. When SCHW died after World War II, a handful of people led by long-time activists Jim Dombrowski and former New Deal official Aubrey Williams continued SCEF, formerly the educational arm of SCHW. They decided none of the economic issues SCHW had addressed could be dealt with adequately until there was an all-out assault on segregation. As the new black upsurge developed in the mid-’50s, SCEF more and more saw its job as reaching out to white Southerners to involve them in this struggle. It was the only regional organization that was doing so, with the exception of the Southern Regional Council — which did valuable work in bringing blacks and whites together to talk but was not as activist as SCEF and was among those that considered SCEF a red menace.

As SCLC and SNCC emerged, the various investigators pounced upon their associations with SCEF and Highlander to label them subversive too. For example, the Georgia Education Commission (set up in the ’50s not to promote education in Georgia, as its name might indicate, but to preserve segregation) sent a disguised photographer to Highlander’s twenty-fifth anniversary celebration in 1957, and he took a picture of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. That picture later appeared on billboards all over the South with the caption “Martin Luther King at Communist Training School.” (Myles Horton, long-time Highlander director, tells of comments by student activists in the ’60s after the fear of such things wore off. “That’s a terrible ad,” he quotes them as saying. “It doesn’t even give an address for the school.”)

The difference between SCEF and some other groups was that we never denied the charges. We saw it as a matter of principle. By the time Carl and I joined the SCEF staff in 1957,1 am sure there was not a real live member of the Communist party on its board. But SCEF steadfastly refused to adopt a policy that one could not be. At a board meeting in the late ’50s, some members asked the organization to adopt a policy excluding Communists. They said this was necessary for the organization to “survive,” and a long discussion ensued. Jim Dombrowski, who was then executive director and rarely talked in meetings, sat listening. Finally, he said: “I want to point out that we’ve spent all afternoon on this, while the violence of the segregationists is rising all around us. I’ve heard it said that if we don’t adopt this policy SCEF may not survive. I’m not sure it’s important whether SCEF survives — but I think it’s important that American democracy survive. If we adopt this policy we will be supporting the witch hunts that threaten to destroy any hope of democracy.” The question never came up again in SCEF in that period.

So SCEF continued as the whipping boy of the committees. The most innocent thing we did sometimes became sinister. For example, in 1962 Bob Moses, SNCC leader in Mississippi, invited Carl to come to the state and conduct workshops on civil liberties and nonviolence. Carl did so, and later wrote a routine work-report to Jim Dombrowski, who sent it to the SCEF board and advisory committee. There was a leak somewhere, and a few weeks later, the report turned up on the front page of the Jackson Daily News, with a banner headline: “Red Crusader Active in Jackson Mix Drive.”

That created consternation in the Atlanta offices of the Voter Education Project, which was funneling money into Mississippi, and in the Southern Inter-Agency Group, a meeting forum of civil-rights groups that had excluded SCEF from membership. The fury of these groups, interestingly, was not directed at the Jackson Daily News, but at us. Before it was over, SCEF found itself accused of deliberately sending Carl to Mississippi (and then leaking the report to the press) to stir up trouble.

By that time, SNCC was tending to ignore the witch hunters, and SCEF had a close relationship with the student movement. But it had not always been that way. When SNCC formed in 1960, the students soon heard that there were people who were dangerous and should be avoided. Charles Sherrod, one of the early activists, later described the effects: “Somebody said we should get in touch with that group, then we heard it was red, and somebody suggested another group, but we thought it might be red. Pretty soon we began looking at each other and wondering which bed they were under. Finally we decided to forget all that and go after segregation.”

But at the second SNCC conference in the fall of 1960, when the students were selecting organizations to have “observer status” at their meetings, there was a long debate as to whether to include SCEF (which they finally did). And in 1961, when SCEF wanted to help carry the inspira70 tion of the black student movement to white campuses and raised $5,000 for SNCC to set up a “white student project,” they debated furiously whether to accept the money. They finally did so, and white Alabamian Bob Zellner went to work on the project — but only after withstanding pressure from Alabama’s attorney general, who called him in to warn him about “Communists” who were “using” the movement.

The pressures were great on people in our position to accept an assessment that we were a liability and to fade from view. I remember the fall of 1961, when Zellner, Bob Moses and others were in jail in McComb, Mississippi, and Jim Dombrowski raised $13,000 in bail to get them out. Jim was planning to take the money to McComb. I happened to be in the Atlanta SNCC office the night before, and there people were worried about the effects of publicity around Jim’s trip. The fears were far from foolish fancy. All through that period, as Jim Forman reports in his book, The Making of Black Revolutionaries, SNCC was being told by big foundations that they’d never get any money unless they quit associating with SCEF. I got caught up in the fears in Atlanta, called Jim and asked him to send the money but not to go — and he did that. I always regretted that phone call.

Later, the Southern Student Organizing Committee (SSOC), a white group stimulated by SNCC, had the same problem. Those who formed SSOC turned to us for advice as they organized. But when they started looking for funds, Southern Regional Council leaders told them to stay away from us if they wanted to get any.

They did not do so entirely. One SSOC founder who had joined the SCEF board resigned as a gesture, but they kept in touch. Before the 1964 Summer Project, SSOC decided to set up a “White Folks Project” to try to reach poor white Mississippians. They planned their own training session during the SNCC orientation at an Ohio college. It was all financed by the National Council of Churches (NCC). SSOC asked Carl and me to serve as consultants. When we arrived, a SSOC activist met us at our car and said, “Let’s get out of here.” He whisked us away to a professor’s house — where we conducted a workshop, sub rosa, and where it was explained that those running the training program had said we could not attend. Before I left, I saw Bob Moses on the campus. “I’m sorry,” he said. “We fought a battle with NCC to get Myles Horton accepted as a participant, and the Lawyers Guild. You and Carl and SCEF were just more than we could win.”

For this same training session, SNCC had ordered quantities of a major pamphlet I had just written on HUAC, outlining its dangers to the Civil Rights Movement. The pamphlets disappeared on the first day, and Bob Zellner asked an NCC official where they were. “I took them up,” he replied — and the pamphlets were never seen again.

It was not just words that were used in these attacks. The Tennessee investigating committee admitted it could find nothing “subversive” about Highlander, but its sensational hearings set the stage for a court case against the school. It was eventually closed, and one fine night someone burned it to the ground. In 1963, the Louisiana committee instigated a raid on SCEF’s main office in New Orleans, arrested its officers and took all its records, later turning them over to Senator Eastland. The charges were violation of Louisiana’s anti-subversion law by belonging to groups (SCEF and the Lawyers Guild) listed by HUAC.

None of this destroyed the organizations under attack. The Lawyers Guild experienced a revival in this period. Highlander ultimately built a new center near Knoxville and thrives today. SCEF ultimately won the Louisiana case in the Supreme Court and became stronger, although the attacks continued throughout the ’60s; it was only done in later through a different set of events that divided it in the early ’70s.

But, overall, these attacks did weaken the Movement. One notable result was to scare away many white Southerners who might have participated. It was hard to convince blacks that their striving for freedom was a subversive plot, but many whites who could withstand economic pressure and physical danger were frightened by being called traitors to their country.

The real question, at this late date, is why. Since none of the groups under attack was really advocating communism, what was the power structure afraid of?

In the wake of World War II, the U.S. power structure moved to establish what they called “the American Century” in the world and to roll back the small gains in power that had been won here by mass movements of the ’30s; thus, Cold War abroad and witch hunts at home. In the late ’40s and early ’50s, many organizations pressing for broader human rights — including such militant black groups as the Southern Negro Youth Congress and the National Negro Labor Council — were crushed; the CIO was split and its most militant unions expelled, those that were the most anti-racist and committed to organizing the South; peace became a treasonous word; many people fell into inactivity; the “silent ’50s” were upon us.

Thus, although there was always some “resistance movement” against the repression, by 1955 the country was essentially quiet on social issues. Then, all of a sudden, a new Freedom Movement burst forth, starting in Montgomery. The longing of black people to be free was just too powerful to be contained. In the midst of one of the most repressive periods of our history, it erupted anew - and ultimately broke the pall of the ’50s and set this country’s people in motion again in search of answers to social problems.

But the new Movement developed with no direct links to its predecessor movements. Without doubt, it was impoverished by that fact. For example, between 1937 and 1949, the Southern Negro Youth Congress (SNYC) had mobilized thousands of people, including workers it helped organize into unions. But it was a long time before anyone in SNCC even knew that just a decade before there had been a youth organization in the South with virtually the same initials as its own. Paul Robeson, spiritual leader of earlier struggles, sang across the South for trade unions and people’s rallies in the ’40s, but he never sang for the new student movement: by the early ’60s, he was in exile, and even if he had not been, it is doubtful he would have been invited. (It was only after some struggle that SNCC decided to invite Pete Seeger — who had been attacked by HUAC — South to sing in the early ’60s.) Also in exile was Dr. W.E.B. DuBois, one of the great moral giants of all time, who just 15 years before had inspired a SNYC conference of 1,000 people in Columbia, South Carolina, with his “Behold the Land” speech, urging young people to stay in the South and transform it.

For its own reasons the Freedom Movement of the ’50s and early ’60s focused on simple issues — the symbols of racism in segregated public accommodations, the all-important right-to-vote. That made it different from the freedom organizations of the earlier period. None of them were “revolutionary” in any stereotyped sense, but their basic characteristic was that they merged the issues — racism with the struggles for world peace and against colonialism, and the struggle for economic justice. And since they related to an aggressive labor movement, they were building powerful coalitions. By the early ’50s, it had come to be considered treasonous to suggest that our economic system might have flaws. For example, at Carl Braden’s 1954 sedition trial, the prosecutor scared the jury by reading an article Carl had written saying unemployment was increasing in Louisville, which it was. “Does this mean, Mr. Braden,” the prosecutor asked, “that you don’t think our economic system works?”

The demands of the new Freedom Movement, although troublesome to Southern segregationists, ultimately could be absorbed by the society as it was. The real danger to those in power was the possibility that this Movement would turn to questions of economic justice and a new world view and make demands that would require basic changes in economic and political structures.

That’s where I think we who were under the witch-hunting attacks came in. All of our organizations had roots in a period when the varied issues were seen as related. That made us potentially a threat — that, and the idea of black-white unity for change, which we were advocating.

In this context, we in SCEF saw our struggle for our right to be a part of the Movement as much more than an organizational thing. It was sometimes an embarrassing battle; there was always the haunting question, “Is it self-serving?” Yet instinctively we knew an important issue was at stake — the right of a social movement to explore, to hear ideas (even though we might not be expressing any dangerous ones), the right not to be fenced in. An historian asked me recently what role, if any, radicals (or “the left”) played in the Southern Movement of the ’50s and ’60s. I guess we were what passed for radicals and “the left” at that time, and this article is my answer to the historian’s question. Our role was to fight for our right to exist, to be recognized as a legitimate force.

So SCEF struggled consistently for its right to participate, and when attacks came we used them as platforms from which to reach people with our program of enlisting white Southerners in the anti-racist Movement. But we also explained in multiple papers, pamphlets and oral discussions our position on what we called “civil liberties,” and their importance to civil rights. And we informed people about the role of the witch hunters and their committees.

Thus, when HUAC announced hearings in Atlanta in 1958, black SCEF leaders organized an open letter signed by 200 Southern black activists, demanding that the committee stay out of the South. It was the First open attack of that scope on HUAC anywhere, and as a result the National Committee to Abolish HUAC emerged; it led that fight for 72 more than a decade and finally succeeded. In my opinion, HUAC’s trip south in 1958 was the beginning of its end, for that brought black civil-rights forces together with white civil-libertarian forces, and the combination was unbeatable.

Carl Braden was subpoenaed to those Atlanta hearings, and he refused to answer any of HUAC’s questions, saying “My beliefs and associations are none of the business of this committee” — that is, standing on the First Amendment. In 1961, he went to prison for a year for that position, after the Supreme Court upheld his contempt conviction, along with that of Frank Wilkinson, sparkplug of the movement to abolish HUAC. But by 1961, we had carried the campaign against HUAC all across the South, and during the year Carl was in prison I traveled about speaking on the subject. In the fall of 1961, SCEF sponsored a major conference in Chapel Hill on the theme “Freedom and the First Amendment,” and several hundred people came, our first mass conference of this period. The new Movement was breaking through the fear.

As we struggled for the right to exist, we won some strong allies within the Movement, and there were important expressions of human courage. It took an additional dimension of bravery to defy those who shouted “traitor.” Some people who could stand up to police dogs and cattle prods couldn’t deal with this.

The Reverend Fred Shuttlesworth, who led the mass movement that broke segregation in Birmingham, was one who had both kinds of courage. He met SCEF people in 1957, after his house was bombed and not long before he was almost killed trying to enroll his children in a segregated school. He began to work closely with SCEF, joined its board, invited it to hold Birmingham’s first integrated conference in over 20 years, and never let anybody tell him to stay away from us.

In 1963, at the height of the Birmingham Movement, Fred accepted election as president of SCEF. He was also a founder of SCLC and was then its secretary. In his book My Soul Is Rested, Howell Raines notes that after the big Birmingham demonstrations in 1963, Fred was never again accorded his previous prominent position in SCLC. Raines thinks this was because he disagreed with Martin King over tactics in Birmingham and was never forgiven for this by King’s aides. My own opinion is that, if indeed Fred’s SCLC status changed, it was because this was also when he was elected president of SCEF.

Fred knew there might be concern in SCLC about his election. He still tells about how he broke the news to SCLC leaders. He, Martin, Ralph Abernathy and Andrew Young were on their way to a speaking engagement. “Oh, I want to tell you,” Fred reports the conversation, “I have been elected president of SCEF, and I have accepted. Now I know some people may feel that causes problems for SCLC, and if you think it does, I will resign . . . from SCLC.”

Martin hastened to assure him that this was not necessary. Although there was apparently divergence of opinion within SCLC on this issue, Martin himself always rejected the witch hunters’ attempts to isolate SCEF. He defied a barrage of criticism to initiate a clemency petition as a protest when Carl went to prison in the HUAC case. Soon after Carl left prison in 1962, I was invited to speak at the annual SCLC convention in Birmingham. It was a strange invitation; I was asked to speak on nonviolence, and there were plenty of people in SCLC more expert on that than I. Martin said he added my name to the speakers’ list because there were no women on it, and he didn’t think that was right. But there were plenty of other women available too. When I spoke, the presiding officer asked Carl and Jim Dombrowski, who were in the audience, to come to the stage also; and after I finished what I think was a quite mediocre speech, Martin himself came to the stage to give an “appreciation.” I think it was his way of saying to the world that he was not going to be a part of the witch hunt or be intimidated by it.

It also provided the witch hunters with one new weapon. A picture was taken that day showing Martin at the microphone with Carl and Jim and me in the background. Later that fell into the hands of the Louisiana Un-American Activities Committee, and they published it with great fanfare in a three-volume dossier on SCEF. During hearings, the committee counsel announced that the committee had communicated with Dr. King to give him an “opportunity” to clear his name by repudiating SCEF. But, the counsel said sadly, “No answer whatsoever was received from Martin Luther King.”

For those of us who knew Martin, that was no surprise.

Ella Baker, long-time NAACP organizer and unofficial “godmother” of SNCC, was another who challenged the witch hunt. Carl and I met her during our 1950s sedition case when she stepped out of the role dictated by NAACP policies and organized support for us. In early 1960, she and Carl worked together on a voting-rights hearing in Washington, despite pressure on her to stay away from it. She told the students that they must not be afraid of those the power structure told them to fear. “The problem in the South,” she said, “is not radical thought, or even conservative thought; it’s lack of thought. We’ve got to break that pattern, and we can’t do it by letting the opposition tell us whom to associate with.”

Another person who took a courageous lead was the Reverend Wyatt Tee Walker, executive director of SCLC in the early ’60s. It was Wyatt who argued at that 1960 SNCC meeting that it should not exclude SCEF from its observers. In 1962, Wyatt got sold on the idea of having a big conference in Atlanta that would bring all the civil-rights and related groups together to say “no” to witch-hunting. The proposed conference was the idea of Eliza Paschall, then leader of Atlanta’s Human Relations Council.

Both Eliza and Wyatt learned some facts of life when they started trying to enlist support from other organizations. The Southern Regional Council, which Eliza was sure would go along, equivocated for months — and finally said no, as I knew they would, since at that time they were part of the problem, not of the solution. That didn’t faze Wyatt, because he was sure he could get support from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). He wrote their national office in New York, then went to see them — and waited all one afternoon in an anteroom without ever seeing anybody in authority. He came back to Atlanta furious.

Dottie Miller (later Dottie Zellner, then on the SNCC staff) told me about Wyatt’s report to her. At that time, SCLC was very close to President Kennedy.

“Can you imagine,” Dottie laughed. “He’s got an open door to the White House, and he can’t get into the ACLU.”

With doors of the more “respectable” organizations closed, the proposed Atlanta conference never happened. Instead, the next summer, 1963, Ella Baker organized a workshop on the topic, sponsored by SCEF; both SNCC and SCLC supported it, and lots of activists came. The ideas discussed there — the importance of rejecting all labels and claiming the freedom to explore all ideas — were spreading slowly through the movement.

Only a few years later, of course, the Movement and the country changed in profound ways. The mass movements generated by the black upsurge in the South swept away much of the fear, pulled the fangs of HUAC, and created an atmosphere in which people’s movements were setting the country’s agenda. The Freedom Movement, despite the efforts of those in power to confine it to narrow issues, burst out of the set bounds again — and did indeed move on to economic issues, the issue of war and challenges to the political structure. SNCC moved in that direction when it supported the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party in its refusal to compromise with politics-as-usual at the National Democratic Convention in 1964; it was at that moment that the attacks began that eventually destroyed SNCC. SCLC moved in that direction when Dr. King came out against the Vietnam War, later called on people of all colors to join a Poor People’s Campaign, and went to Memphis to support striking workers.

What with mass movements now having burst the established parameters, those trying to control the society apparently knew the old methods had failed. “Words can never hurt me, but sticks and stones may break my bones.” Those who wanted to keep things basically as they were turned to other methods of repression in the late ’60s and early ’70s — but that’s another story.

Now as the 1980s begin, rumblings of yet another period of repression are coming out of Washington — and new people’s movements are emerging. But the movements of this decade start from a very different point from those of the ’50s and ’60s, and it is to be hoped that they will not let any reincarnations of the witch-hunting committees deter them from their path.D

Tags

Anne Braden

Anne Braden is a long-time activist and frequent contributor to Southern Exposure in Louisville, Kentucky. She was active in the anti-Klan movement before and after Greensboro as a member of the Southern Organizing Committee. Her 1958 book, The Wall Between — the runner-up for the National Book Award — was re-issued by the University of Tennessee Press this fall. (1999)