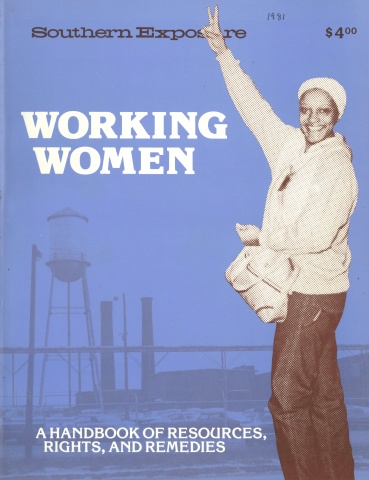

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 4, "Working Women: A Handbook of Resources, Rights, and Remedies." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

Helping women to get and use information on child care, transportation, apprenticeship and job openings, and workers’ rights is the focus of programs for working women sponsored by the American Friends Service Committee in North Carolina, Kentucky, Virginia and West Virginia. These programs share a community-based approach and a common dedication to help women take control over their own lives by building networks and support groups around work issues. Each has organized a local advisory committee made up of black and white local women workers.

Women in the Work Force is located in High Point, North Carolina, where most women work in low-paying jobs in textiles, hosiery and furniture. They have little knowledge about their legal rights, and in most cases lack union protection.

“The factories segregate women into traditional jobs where they are paid low wages, treated in traditional childlike ways, and afforded traditionally little respect, recognition or opportunity,” explained Tobi Lippin, former director of the program. “The reality of the risks faced by women working to improve work conditions often limits their vision, making them accept the status quo.”

One way to help women in their workplace struggles is to provide them with information. A series of pamphlets produced by Women in the Work Force, What Every Woman Worker Should Know About. . . is proving very popular. Pamphlets cover discrimination, minimum wage and overtime laws, the National Labor Relations Act, unemployment compensation, job safety and health, and sexual harassment. A newsletter, now going to 1,500 people, and a series of workshops have made Women in the Work Force known in the community. Not only women with problems call the program; so do business and government leaders seeking to know what women workers want. In group meetings organized by Women in the Work Force, women discuss problems of sexual harassment and race and sex discrimination.

In furniture manufacturing, High Point’s major industry, most women work in the finishing department. In the spring of 1981, Women in the Work Force conducted a survey in finishing to determine what specific health hazards the women face, what chemicals are used, and what health problems they are experiencing. The staff from the project visited more than 60 women at their homes to discuss furniture work and to develop a support network. Researchers on health and safety from the University of North Carolina helped to build a solid base of information.

In June, Women in the Work Force organized a “Furniture Workers Nite” at the public library, attended by workers and supervisors, as well as by people from other organizations. After viewing a slide show, “Your Job or Your Life,” talk centered on problems with chemical fumes and wood dust and on how to achieve changes through collective action. The main concern for all turned out to be air quality — the chemical fumes and wood dust.

By encouraging openness and by providing information and technical assistance when needed, Women in the Work Force has been able to help women with problems of safety and health, unemployment compensation and discrimination. As a result, one woman won over $800 in back pay from an employer who had discriminated against her because of her race. Another woman was able to reverse a state Employment Security Commission decision on her unemployment compensation and is now entitled to receive her benefits. And yet another was awarded $ 1,700 in back pay after a local hotel discriminated against her because of her pregnancy.

In cooperation with a coalition of local groups, including the NAACP, Women in the Work Force is undertaking an effort to ensure affirmative action for women and minority men in local construction projects that are wholly or partially funded by the federal government. In the spring of 1981, the program investigated new federally funded local construction projects and found only one woman working as a laborer or cement finisher, and all the minority men in traditionally low-paid jobs. At a July meeting over 100 women and minority men wanting construction jobs shared discrimination experiences. Information on new construction projects was handed out, and the basis laid for further organizing.

Three other closely linked programs are located in Appalachia, where women live in small towns or isolated hollows and the nearest industrial jobs are several hours away. In these areas, it is impossible for a working women’s program to concentrate on any one issue. Women wishing to enter the employment market come for information and have a whole host of problems. They may begin by needing their G.E.D. — General Equivalency Diploma — to qualify as high school graduates. They may need to borrow gas money to drive the long distances necessary to apply for training or work. Others may need the support of other women in the same situation to gain the courage to stand up to a husband or to parents who are opposed to their working.

At the Logan, West Virginia, office of the New Employment for Women Program (NEW), a woman came in recently who had been deserted by her husband. The utility company had cut off her power, and her children were cold and hungry. After the staff helped her get her power back on and some groceries in the house, they encouraged her to enroll in a G.E.D. program. Next she entered a program to get training to work as a miner. Now she is the first woman miner hired by a local coal company, working in the office above-ground to keep in radio communication with all the miners.

Their efforts are not always appreciated. Recently someone shoved a note under the office door: “Nigger — Nigger Lovers — Commie — Leave.” Sarah Davis, a black woman who chairs the advisory committee, is also harassed. Recently one of her children was called to the phone at school and told to hurry home because his mother was dying. He found Sarah in good health when he finally reached home, frightened. On the night of a recent meeting, Sarah returned to her house to find the word “Nigger” scrawled on her front door.

However, during the past year, NEW was successful in placing about 80 women in jobs: 50 in traditional and 30 in nontraditional employment. Of these, 10 are working as deep miners and 20 are in mine-related jobs. NEW and the two other AFSC programs in Appalachia cooperate closely with the Coal Employment Project in facilitating training programs for would-be women miners (see p. 47).

In Hazard, Kentucky, the Women’s Employment Information Service (WEIS) works with women who are already employed as waitresses, secretaries, social workers and teachers but want to know how to receive training for higher-paying jobs in the mines or heavy construction. Recently almost 100 women applied for construction jobs with a federal highway project, but only five were hired.

The program also helps women to enter more traditional jobs, and works to develop networks through which local working women give financial and emotional support to each other. When one woman, who was studying heavy equipment operation, came home and found her trailer burned to the ground, another woman drove her around until she found another place to live. Later, when the woman was dropped from the training program because she was absent due to the fire, the others helped her get into a program of training in diesel mechanics.

At Big Stone Gap, Virginia, a strong and active board of black and white low-income women has for two years guided Women’s Work World, the third of AFSC’s programs in Appalachia. A great deal of Women’s Work World’s effort has gone into trying to persuade a local community college to offer training programs in nontraditional employment for women. The program has also referred local women to six-month fellowships offered by the Southern Appalachian Leadership Training Program and has been involved in setting up safe house's for abused women. A strong network of support for the victims of domestic violence has developed. Women also help each other in finding and securing nontraditonal jobs.

Custom, discrimination, corporate practice and male prejudice all block women everywhere from having their fair share of good-paying jobs. The chains that bind women are so old that they sometimes become internal as well as external. Programs of support and information-sharing are one way in which women can help each other break those inner chains, and confront the true oppression which surrounds them.

Tags

Margaret Bacon

Margaret Bacon is Assistant Secretary for Information and Interpretation of the American Friends Service Committee. (1981)