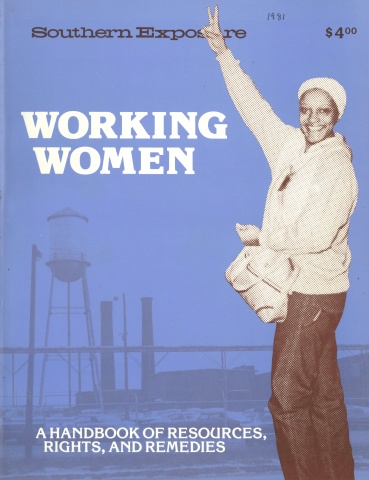

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 4, "Working Women: A Handbook of Resources, Rights, and Remedies." Find more from that issue here.

At the age of 27, Dora Guerra found herself the head of a household that includes two small daughters. One girl suffers from cerebral palsy, and about twice a year the child undergoes surgery. “I got separated all of a sudden. I never expected it. And I found myself on welfare and what they give you is very little. I couldn’t survive on that money.”

Mary Dominguez, also 27, divorced her husband and must care for three young children. She quit her last job because of sexual harassment. “I tried, but I couldn’t get a job any other place. It’s hard. I’m getting a hundred dollars a week from unemployment. But still I need insurance for my two children.”

Both women applied to the Low Income Women’s Employment Model Program of National Women’s Education and Employment, Inc. (NWEE), which targets single parents receiving government payments, displaced homemakers and unemployed and underemployed women, particularly family heads of Hispanic background.

Upon acceptance into the program, Guerra and Dominguez began an intense three-week training to help prepare them for employment. They assessed their skills, began planning careers and developed positive attitudes toward the possibilities of employment. Instructors and counselors, many of whom are NWEE alumnae, aided them in organizing an individual employment plan which includes a commitment to lifetime employment, developing a resume and financial counseling. They received academic and career testing and assertiveness training. They practiced job interviews in classes where the students acted out the roles of prospective employer and employee. If job openings came up during training, NWEE drove the women to the interviews. The fourth week of the program concentrated on job placement. Instructors discussed child care and its problems with the class. More help with meeting the need for affordable, trustworthy child care is on the way.

This is the story of an employment project in San Antonio, Texas, that attempts to get women off welfare rolls and into jobs — and succeeds. It is the story of the battle waged against the glaring inadequacies of the welfare system. But most importantly, this is the story of the women who go through the program. The women who alone face the difficulty of feeding, clothing and sheltering their children. The women who wait in the food stamp lines and still run out of food in three weeks. The women who may not finish high school because they drop out to enter low-wage service industry jobs to help feed their younger brothers and sisters. The women, mostly chicana, who have seen lifelong discrimination as women and as members of an exploited ethnic group. They don’t see the subsistence level wages offered them as an alternative to welfare, which at least pays for the children’s doctor.

Welfare recipients face a third barrier to employment: the stereotype of the welfare recipient who has it made. She is unemployable because she doesn’t want to work. Nothing could be further from the truth, as Lupe Anguiano, the founder of NWEE, discovered.

Anguiano — migrant worker’s daughter, United Farm Workers organizer, founding member of the National Women’s Political Caucus, former nun with a master’s degree in administration and education, welfare reform activist — began developing the program in 1973 after she moved from California to San Antonio. She accepted a job as executive director of the Southwest Regional Office for the Spanish Speaking under the sponsorship of the National Council of Catholic Bishops. Making welfare reform a priority of the office, Anguiano moved from housing project to housing project, living for seven months with women and children receiving public assistance.

She accompanied women to welfare offices, doctors’ offices and food stamp offices, experiencing with them the frustration of trying to find a babysitter and transportation and then waiting sometimes a full day to accomplish the goal. They were met by agency employees who seemed to Anguiano indifferent, and even hostile. Not surprisingly, she found the women even more critical of welfare than its conservative opponents.

“What happens is that a woman steps into that office, and immediately that’s her doom,” Anguiano said. “If she dares move out of that little web, they’re going to take one thing or this thing away from her.

“Women have been socialized to be dependent, and they walk into that situation, and they really get destroyed by it,” she said. “But that’s how welfare is. It’s just an empire that destroys the lives of women — of young women and their families.” Six women attempted suicide during the time Anguiano lived in public housing. Four succeeded.

In an economic system which feeds on the lives of workers, chicanas are devoured. U.S. government figures show that almost half of all Mexican- American women who are 16 years of age or older do not go beyond the eighth grade in school. The language barriers they face at school and on the job discourage some from finding work. Other factors which tend to discourage chicanas are the low occupational status offered them, the high unemployment rate for Mexican-American women and the lack of child care, especially the lack of affordable facilities. In 1970 one of every eight Mexican-American families subsisted on public assistance, more than twice the rate for all U.S. families. Chicana feminist Minta Vidal notes that “Raza women suffer a triple form of oppression: as members of an oppressed nationality, as workers and as women.”

A Mexican-American woman who wants to work outside the home not only must overcome discrimination in the workplace but also restrictions within her own culture. Necessity, tradition and religion combine to force her into the role of wife and mother.

Gloria Reyes, 47, NWEE’s employment counselor who completed the NWEE training herself in 1979, said, “A lot of the women, and I am referring to the Latin women, because I am Latin, are held back because of our culture, our tradition, our religion. When you got married, you got married forever. And we are prime victims, because we are geared to believe that the man is lord master.”

Reyes tells of one young woman who was recruited through NWEE for the Houston police force. “She was embarrassed to tell me that her parents said that only bad girls left the house. And she said, ‘What can I do, I have to listen to my parents.’”

NWEE succeeds because it takes care to address the special needs of the women it serves. Again and again, NWEE women point to their new-found self-esteem, the talents and strengths they discovered with the encouragement of staff members like Reyes and with the support of their classmates. Ann Marie Ilva, a classmate of Guerra and Dominguez, explains, “Before, you just went out and made an application, and that’s it, and then you realized, kHey, they don’t give me this, and they don’t give me that.’ But you didn’t know you were supposed to ask, that you could ask.”

Often these discoveries take place in the “Magic Circle,” a peer-group counseling method of self-discovery which forms a basic component of the program, helping the women develop self-reliance and assertiveness.

The Magic Circle has been a part of NWEE and its San Antonio project since its beginnings in a small group of women calling themselves Mujeres Unidas (United Women), sponsored by the Southwest Regional Office for the Spanish Speaking. Mujeres Unidas was formed in 1973 for “self-help” by women receiving public assistance payments and living in the housing projects Anguiano toured. Anguiano’s stay in the projects and a survey indicated that the majority of families in the projects were headed by women and that they had skills and talents used only in volunteer work. The contacts Anguiano and the surveyors made led to house meetings. Mujeres Unidas grew out of the discussions in the women’s apartments.

In November, 1973, the group declared a wellpublicized “Let’s Get Off Welfare” campaign and sent back their welfare checks in anger. The women’s pleas for a better life were met in part by the San Antonio Kiwanis Club, which gave scholarships to train the women for jobs, forming the first partnership between low-income women and private business, a partnership Anguiano hopes to duplicate throughout Texas and the United States.

In addition to involving the business community by asking it to pay for training, NWEE brings area employers into its classrooms where, often for the first time, they meet women on welfare. They must confront their own biases and replace them with the realities faced by poor women at the same time as they conduct field trips and workshops for the women. Changing entrenched attitudes about the poor and welfare by involving the community, forcing the more powerful to “touch the lives of people,” as Anguiano says, is one of the keys to NWEE’s success in placing low-income women in jobs. Business people who participate in NWEE training and placement gain a stake in the lives of women they can no longer ignore or write off as welfare chiselers.

“I decided what I was going to do was concentrate on working with the women and with employers. What I do now is I go into communities and I meet with the chambers of commerce, I meet with employers, I meet with low-income women. I meet with people who are really concerned with improving the quality of life for both women and their children. And together we work on our model,” Anguiano said.

The NWEE Alumnae Association, made up of the program’s graduates, worked for months to come up with a proposal to solve the working mother’s biggest dilemma, child care. NWEE instructor and graduate Pauline Pezina says, “Proper child care is the number one need women have if they are to succeed in obtaining and retaining employment. We all want to better ourselves — we want to raise our children with dignity and respect.” Pezina marshaled the energies of the association to develop a plan and contact funding sources. Graciela Olivarez, former director of the U.S. Community Services Administration, secured funding to train 20 women as child development specialists before she left the Carter administration. San Antonio College will train the women on the job and in the classroom. In 1982 the alumnae association plans to form a nonprofit corporation to continue the child-care program, which will allow some women to care for children in their homes.

NWEE often channels its students into betterpaying nontraditional jobs, including construction work. Norma Gagne, 39, the divorced mother of three, and Rosemary de Leon, 34, the divorced mother of five, tell two nontraditional success stories. On welfare, Gagne felt “as though the walls were closing in on me.” She became a certified front-end loader operator with NWEE’s help, and says now, “My job seemed especially rewarding when my son told me that he would like to do the same kind of work that I do.” De Leon, who has a sixth-grade education, tried to support five children on $ 135 a month. Now she drives a backhoe tractor, makes close to $200 a week and says, “I feel as though I’ve really done something.”

Since 1973, about 1,600 San Antonio women have completed the program. Ninety percent gained employment, and 82 percent still worked at those jobs after a year. At the same time, federal work incentive (WIN) programs in some locations placed only 0.08 to 11 percent of participating welfare recipients in permanent employment.

The San Antonio project operates with a budget of $226,000, at a current cost of about $800 per participant, 20 women are trained each month. The money comes from the city of San Antonio, approved by the city council. El Paso received funding for a project based on the San Antonio model from Governor Bill Clements’s discretionary funds, and a Dallas program has opened with money from the private sector. Denver, Colorado, has started a program, and other communities have requested assistance to follow NWEE’s lead.

Although NWEE’s solutions reach only a few of the millions of poor, Congress failed to endorse a similar national program. Anguiano proposed that women and their families first be assured an adequate monthly income determined on a state’s current cost of living, coupled with training that would assure women of wages they could live on when completed. A third component of her proposal was a provision for support services such as day care, transportation and health insurance.

“The welfare system is so messy, so complicated, so imbedded in making women stay home to take care of their kids and living in poverty,” Anguiano said. “You know, I often sit down at night and I close my eyes and I envision that welfare empire just crumbling down and turning into ashes, and my just going in and burying those ashes. I hate it. I hate that empire with a passion.”

Ann Marie Ilva wants to be trained in the childcare program. She has a two-and-a-half-year-old son. “Here they taught me that you don’t have to stay where you’re at. If you’re willing to take that step, and look for something better, you can.” Ilva echoes the sentiments of other women who explain one reason why NWEE succeeds while federal and state programs with millions of dollars more don’t. Dominguez said, “I see women here, and we each have these problems, and we learn from each other.”

Tags

Janie Paleschic

Janie Paleschic is a single working woman raised in Dallas by a mother who usually worked outside the home and a father who tried to form a teachers ’ union. She is a contributing editor of the Texas Observer and associate editor of Austin Women’s Networker. (1981)