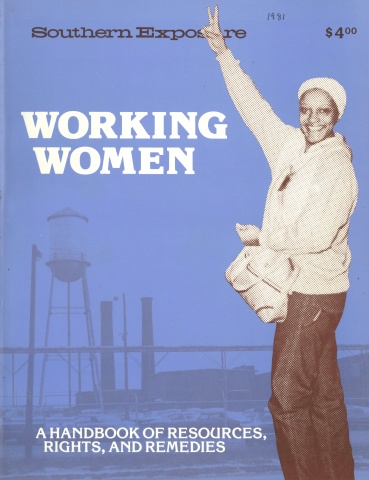

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 4, "Working Women: A Handbook of Resources, Rights, and Remedies." Find more from that issue here.

“What convinced me to help organize the union,” says Betty Watkins, a licensed practical nurse (LPN) at Tuomey Hospital, “is that I had worked for 10 years, been away and come back, and it seemed like things were getting worse. I thought maybe a union was the answer. ”

‘‘Unions. I didn’t know anything about unions except what I’d learned in high school,” says Dolores Singletary, another LPN at the same South Carolina hospital. ‘‘I knew the doctors had the A.M.A. (American Medical Association) to represent them. What did we have?”

‘‘After eight years I just got tired of nursing supervisors playing favorites, ” says nursing assistant Shirley Williams. ‘‘There was no place to take your grievances, and no matter how well you worked, your raise was just the increase in minimum wage. ”

These black women, once unfamiliar with unions and suspicious of them, became leaders in the effort to establish a unit of 1199, the National Union of Health Care and Hospital Employees, at Tuomey Hospital, a private 213-bed institution located in the farming town of Sumter on South Carolina’s coastal plain. Theirs is a story of courage and persistence in fighting some pervasive cultural assumptions: that doctors are gods, that unions are bad and that blacks and whites cannot unite and risk their jobs to improve their lives.

The union struggle began at Tuomey in October, 1979. When it was all over — after bitterly contested union elections in August, 1980, and prolonged contract negotiations which nearly produced a strike instead of an agreement in March, 1981 — approximately 450 hospital employees, belonged to the bargaining unit and were protected under law. Three-quarters of them were black women. Thus Tuomey was the first private hospital in North and South Carolina, Virginia and Georgia (outside Atlanta) to be unionized.

“We didn’t know anything when we began,” says Shirley Williams, who edits the “1199 Injection” newsletter and is a never-say-die union delegate. “We had our union reps to lead us through situations — Bill Chandler, LaBrone Epps and Arthur Laudman — but we had to organize ourselves, get committees and keep working. There were peaks, but there were a lot of valleys. In the end, it was fun. We’d have midnight strategy sessions and be up to dawn to distribute literature. We set up information tables in the cafeteria and assigned people to talk with workers at certain tables. After work we’d go visiting to employees’ homes and talk with them there.”

By the time the organizing campaign was in full swing in the spring of 1980, union activists made sure that Tuomey employees were constantly being offered election authorization cards and petitions to sign and buttons that read “YES” and “1199.”

“Education and communication was our job,” says Betty Watkins. “We learned how to do it by doing it. And we’re still learning.”

“The organizers from 1199 told us what was going to happen and what to expect,” says Dolores Singletary. “They told us the union was worthwhile and something we could do. They didn’t whitewash us.”

Two functioning unions in Sumter, the Postal Workers and the United Furniture Workers of America, from the Georgia Pacific furniture plant, also gave the blossoming organization their advice and support. The NAACP backed them, and so did more than 60 churches.

“The hospital always tried to make the union seem like a racial issue, like it was the blacks causing the trouble,” says Shirley Williams. “We knew — and the whites knew — that was the boss’s tactic to split us, but we were solid. When we were talking about striking in January and February, the hospital management and doctors were taking whites aside and asking them did they know what a strike meant. They said if there was a strike it would be all black people out on that line.”

Try as the hospital administration might to break the union along racial lines, it never succeeded. In fact, some of the most vocal union supporters were two older white women, Mildred Player and Dorothy Boykin.

Failing to divide the workers along racial lines, Tuomey Hospital administrator Ralph Abercrombie and the Board of Trustees resorted to a host of other union-busting tactics to put down organizing efforts.

They hired Columbia, South Carolina, attorney Julian Gignilliat, an anti-union consultant for the South Carolina Hospital Association and other clients, to advise them how to stop 1199. Gignilliat, who has since become the hospital’s representative in arbitration procedures, instituted get-tough measures: extra security guards were hired to patrol every floor; doctors were asked to pressure individual employees not to join the union; head nurses and other floor managers were asked to look out for and report any “suspicious” activity; mandatory meetings were held at yvhich hospital policy would be discussed; and the board of trustees sent every Tuomey employee a letter explaining why the hospital didn’t need a union.

“At one of the mandatory meetings, Mr. Abercrombie stood up and read us a speech,” says Singletary. “Gignilliat would sit right next to him, be with him whenever he appeared. Remember, these were supposed to be discussions. The message was, ‘Give us time. We may have made some mistakes but we’re going to change all that. We’ve repainted some halls already.’

“A lot of people spoke up — RNs, orderlies, assistants, black and white — and asked questions about wages, retirement benefits, leaves and other things. Right after that meeting in May, eight black workers who had been among those challenging Abercrombie were fired.”

The dismissals backfired. Worker grievances were given favorable and extensive local press coverage. Organizers were besieged with volunteers both inside and outside the hospital willing to write letters, call and telegram the hospital administrator to demand an explanation for his actions. To many uncertain workers, the dismissals were a perfect example of the hospital’s abuse of its power.

“I was looking to those people as our leaders, and they got wasted,” says Debbie Vareen, a ward clerk. “I hadn’t been an organizer up to that point, but I knew I had to help take up the slack. We had gone too far to turn around and quit.”

The firing of eight workers — all black — was just one of dozens of incidents in 1980 which led 1199 to file more than 100 complaints of unfair labor practice with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB). Throughout the organizing campaign, workers had been watched, verbally harassed, threatened with suspension and given written reprimands — these were often given to 60 people at a time — for distributing union literature and talking about the union at times and in places well within their rights. Among other things, the NLRB ruled that comments regarding union organizing had to be struck from employee records. It also ordered the hospital to offer the eight fired workers their jobs back; they chose to work elsewhere.

But no matter how the NLRB finally ruled, the fact is that the union activists had to put up with harassment on the job every day — from the doctors and nurses they worked with and from their colleagues, who were often scared, fhey successfully met these challenges with humor, common sense and stubbornness.

“The doctors would be real polite, open doors for you, talk in the halls, ask if they could take you to lunch,” recalls Debbie Vareen. “If I saw a doctor taking someone aside who I knew was unsure about the union, I’d go up and enter the conversation. My philosophy was, ‘Best join in.”’

Betty Watkins explained her experience this way: “Some doctors warned the RNs that it would make a difference in the way they accepted you if you joined the union. And then they put a fullpage ad in the paper saying they were against it. I let them talk. I hear and I didn’t hear; I see and I didn’t see. I’m like that. I knew where I stood and I said, ‘In time we’ll see.’”

When a crackdown came and employees were required to sign in and out of the ward, union organizers found ingenious ways to move throughout the hospital. They volunteered in large numbers to return wheelchairs to other wards. And some of them signed in and out so many times that the nursing supervisor’s paper work doubled.

To meet the resistance of fellow employees to the union, organizers had to rely on their personal resources.

“I’ve never felt the need to advertise my feelings for the union,” says Betty Watkins. “When the opportunity presented itself I would talk with people about signing a union card. After I kept bumping into the same people who didn’t have anything to do with it, I had the sense not to bother them. I knew that there were people who weren’t speaking to me who had spoken before, but I wanted to do what I wanted to do.

“The hardest people to convince were the elderly nurses, black and white, who had been at Tuomey for years. They have loyalty to the hospital, or to the administrator. Maybe they go to the same church as the doctors - I don’t know. They’ve been in Sumter their whole life and they know who’s doing what to who, and they know someone from when he was raised up as a child. They’re ignorant toward the union. Being in the South they’ve been anti-union their whole life. Union is a bad word in the South.”

Charlene Harvin, who works in Central Supply, found that listening was the most persuasive organizing tool: “Everybody’s got their technique. Mine is not to pass judgment and to get people to take you into their confidence. Some of the biggest problems we had is that people were scared we’d tell if they signed the election authorization card. There was a lot of tension. They had a right to be scared. But people knew I wouldn’t tell, so they’d talk to me. I’d tell them, ‘If you don’t want to be seen with union members, that’s your business. But it’s best to look face to face and get reputable information.’ I’d say, ‘Think about what you’re getting and what you could get,’ and I’d give them a brochure. I got some people to sign cards. It made me feel good to change minds.”

The effort to change minds did not stop in the hospital hallways. The union took its story to local television and radio stations, to newspapers and to the preacher’s pulpit.

“While we were organizing inside, we were organizing outside,” says Singletary.

When a group of doctors bought a full-page ad in the Sumter Daily Item suggesting that Tuomey employees ask themselves, “Do I like unions or just dislike some aspects of the present situation,” the union fought back. They took air time on radio stations and made spots which featured employees telling why they chose the union. These messages were so successful in garnering support for 1199 that the hospital made its own advertisements and had them aired right after the union’s. A group of doctors also organized a radio call-in show. The union staged a debate. Pretty soon, the struggle at Tuomey was being aired all over Sumter.

The union also enlisted the help of dozens of local churches and local businesspeople. Members made trips to ministers’ homes and asked them to speak personally to churchgoers who might be on the hospital staff or on the board of trustees.

Betty Watkins says: “The religious community’s feeling was, ‘If you need us, you’ve got us.’ When we were preparing to strike, ministers announced it and were willing to take up a collection or do most anything. They made people aware of what was going on in their own town. Ministers would come — even if they sat for 20 minutes — to show whose side they were on during contract negotiations. Sometimes, if a business leader or minister couldn’t come, he’d send some member of his family to represent him. For six months of talks, they supported us. Sumter’s a small town. People were influenced by what they saw and heard.”

Tags

Cecily Deegan

Cecily Deegan is a free-lance writer living in Frogmore, South Carolina. (1981)