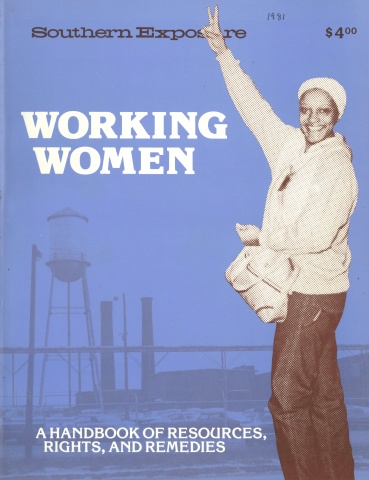

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 4, "Working Women: A Handbook of Resources, Rights, and Remedies." Find more from that issue here.

American workers today take for granted the eight-hour workday and the 40-hour workweek. So established are these principles that few people ever question the long and arduous struggle to make them a reality. But this social goal took many years and countless legislative challenges in every state before the eight-hour day was ultimately realized. This major social reform can be attributed in large part to the organizing and public education efforts of American women.

By 1920, some eight million women worked full-time, but they had little to say about their working conditions. Most toiled 10- to 12-hour days in factories and sweatshops where little attention was given to employee health and safety. Production was the key concern. For the most part, organized labor showed little interest in bringing women into the trade unions. Several explanations are offered as to why, but ultimately we have to conclude that unionists suffered from the male bias which held that women’s real place was not in the workplace but in the home.

So women workers looked to legislatures rather than trade unions for reforms. Laws were drafted to protect women only; men were to be included later after the laws became acceptable in the public mind. Coverage for male workers was perceived as less likely to pass, and indeed many men were already covered under labor union contracts. Laws were proposed to guarantee a minimum wage, shorter hours, restrictions on child labor and health and safety protection on the job.

Having just recently won the right to vote, women felt they could exert more influence in the legislature. In 1922, the Virginia League of Women Voters sponsored a bill for the nine-hour workday and the 54-hour workweek. However, due to strong opposition from business and industry, the struggle was to last 16 years; the Virginia General Assembly finally passed a bill for a nine-hour workday and a 48-hour work week in 1938.

In the course of the effort, the League argued that legislation was necessary because a “10-hour day meant lowered vitality, premature old age, liability to disease, decreased efficiency after a few years of work, no time for social or home life and exhausted mothers of the next generation.” The women lobbyists were successful in persuading some Virginia employers who had voluntarily moved to a nine-hour workday to testify. These employers argued that under shorter hours employees were “more regular, loyal, cheerful and efficient, production is not impaired and there is less labor turnover.”

When the campaign moved to the 1924 legislative session, the lobbying efforts included letter-writing campaigns, a petition drive organized by students at Hollins and Sweet Briar Colleges and public meetings sponsored by community coalitions of groups like the League, the YWCA, the State Teachers Association, the Business and Professional Women’s Clubs and the Virginia Federation of Labor. These meetings were promoted by newspaper publicity, mailings and posters boldly titled “When Women Work They Need Protection.” A second large black-and-white poster showing a woman tossing a baby argued: “America will be as strong as her women.”

Audiences who gathered for the educational forums were often shown a U.S. Department of Labor film “Why Women Work,” which illustrated industrial conditions in different factories across the country. Sometimes a skit was presented for women-only audiences in which women facing various crises in their lives talked of happiness. The line “Love is the best thing in life” was heavily applauded by audiences everywhere.

In addition to these lobbying techniques, women used printed material as another means to educate voters. Most widely distributed for the 1924 campaign was a 26-page study titled “The Shorter Day and Women Workers,’ authored by Lucy Randolph Mason, who chaired the League Committee on Women in Industry. The pamphlet, which sold for 10 cents in order to raise revenues for future League publications, was funded by six Virginia women including the Viscountess Nancy Astor.

The pamphlet spoke about the need for legislators to protect “women in industry or women engaged in manufacturing and mercantile establishments and in laundries.” “The Shorter Day” pointed out that “one out of every four persons employed in the U.S. is a woman.” It reminded readers of history: “For the last century the factory has been steadily taking over women’s traditional occupations” like home-sewing and hypothesized “that civilization needs their work in an era of the factory system just as primitive society needed it before the dawn of history.” Most revealing was the argument that women workers needed their wages because as single women they were sole supporters and as married women they needed an income to supplement the family budget.

While efforts for nine-hour-day legislation continued unsuccessfully for the next decade both in Virginia and in the South, other events served to re-emphasize the need for worker protection. During this time, the Virginia Women’s Council for Legislative Chairman of State Organizations was developed. The council’s goal was to share information and to secure the cooperation of organizations promoting legislation. In an effort to assuage any legislative fears of their being overly assertive and therefore unladylike, the council members promised “to promote legislation without overlapping effort, thus conserving the time of the legislators.” The council included representatives from 20 statewide organizations as diverse as the Florence Crittenden League, the DAR, the United Daughters of the Confederacy, the Housewives League, the Women’s Christian Temperance Union, the YWCA and the American Association of University Women. While the full council membership did not support shorter work-hours legislation, the organization did provide regular updates which were useful to individual supporters and groups.

In 1927, women’s groups helped establish the Southern School for Women Workers. Based in Richmond, the school provided workers’ education for women from the textile and tobacco industry across the South. The students used their education to organize support groups and educational programs in their own communities and to become part of the drive to secure improved conditions for women workers.

Undoubtedly, the 1930 massive strike by 4,000 textile workers, mostly women, against the Dan River Mills in Danville increased the public understanding of the intolerable working conditions found in most textile manufacturing plants. Mill employees began their day at 6:15 a.m. and worked a 10-hour day at a pay rate of $13.75 a week. In addition to low wages and a “stretch-out” system — a work schedule which called for increased production by fewer people — the mill ran a spy operation which served to keep the union out. In support of the strike, the Women’s Trade Union League,* in a campaign to arouse public opinion, sent Southern staff representative Matilda Lindsay into her home state of Virginia to organize traveling road shows in which women spoke firsthand of their workplace problems.

Virginia women’s organizations were quick to support the workers in the drive for better conditions. They collected money for relief for the Danville workers, and community meetings were held to discuss the strike issues. Endorsement of the strike had its own consequences for the women’s groups: for instance, the Richmond YWCA noted a decline in corporate contributions to its operating programs.

In 1930, a group of women from across the region convened in Atlanta to share information and to develop a regional strategy to arouse public interest in securing improved legislation for working women and children. From this networking came the umbrella organization of the Southern Council on Women and Children in Industry, whose goal was to work with and through women’s organizations rather than to create a new legislative group.

The council’s objectives were to lobby regionally for six legislatively mandated standards. First on their agenda was the nine-hour workday and a 50-hour work-week for women in manufacturing, stores, laundries, restaurants and similar occupations. Elimination of night work for women between 10 p.m. and six a.m. in certain occupations was second. Bills on all six standards were introduced into every Southern legislature which met in 1931. Council members found that the most bitter opposition was aroused by bills seeking to limit women’s hours of work.

In 1931, as part of its lobbying action, the council released a 46-page educational study written by Lucy Randolph Mason titled “Standards for Workers in Southern Industry.” It was paid for by the National Consumers League, a New York group founded in 1892 to organize the buying power of women to change conditions of female factory and department store workers. Mason was granted a three-month leave from her position as director of the Richmond YWCA to prepare the publication and to develop the informational network through which the council would function regionally.

In addition to regular action reports, the council conducted personal appeal interviews and corresponded with manufacturers, bankers, lawyers, editors, legislators, governors, ministers, bishops, sociology and economics professors and industrial commissioners in many parts of the South. It sent news stories to 18 major newspapers, which used them to write articles and editorials about the council’s goals. A bibliography of educational reading material was prepared and disseminated, and the council solicited and received endorsements for legislative action from state Parent Teacher Associations, Women’s Missionary Societies, YWCAs, Leagues of Women Voters and Professional Clubs and Federated Women’s Clubs, as well as numerous local groups.

During the Depression of the 1930s, manufacturers attacked the proposed legislation as a threat to industry itself. One manufacturer argued in a public address, “Thoughtful women should see that these are no times to try to force lower hours upon an already burdened industry.” By 1931, most Southern states had laws limiting women’s work to 10 to 12 hours per day. But enforcement of those laws was lax: even where departments of labor existed in the South, they were underfunded and employed few inspectors.

After being repeatedly introduced, the bill for a nine-hour workday for women finally passed both branches of the Virginia legislature in 1938, culminating the campaign begun some 16 years earlier. The Virginia Labor Department estimated that over 100,000 women were expected to receive shorter hours under the new law. Virginia editorials boasted that the Old Dominion had “once again shown its leadership” within the region for its role in offering women workers the best state coverage of its kind regionally, and counseled other Southern states to follow Virginia’s lead.

However, the eight-hour workday came several months later that year when Congress enacted the federal Fair Labor and Standards Act. This legislation protected all workers involved in interstate commerce. It provided for a minimum wage and for the eight-hour day and the 40-hour work¬ week with time-and-a-half pay for overtime. Beginning in 1940, American workers finally received the protection they had labored so long to achieve. Always intolerant of federal interference, however, Virginia lawmakers left the irrelevant state law specifying nine-hour days on the books until 1974 when it was finally repealed as part of a general code revision.

* The WTUL was a national organization founded by female unionists and upper-middle-class reformers. It was geared towards getting working women to join trade unions.

Tags

Betsy Brinson

Betsy Brinson is an organizer and educator with an interest in helping women learn their own history. She is the executive director of Southerners for Economic Justice and former director of the ACLU Southern Women’s Rights Project. (1981)