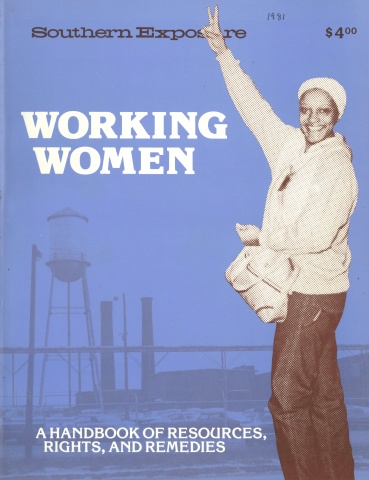

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 9 No. 4, "Working Women: A Handbook of Resources, Rights, and Remedies." Find more from that issue here.

Joan Griffin is a hospital worker, a single parent, a homeowner and chief shop steward for her union local. She wants to be the president of the local.

I’ve been working for the state for 12 years [at Charity Hospital], I went to public schools and graduated from Booker T. Washington High School. I worked a couple of days in a factory, then did some campaigning for Moon Landrieu the first time he ran for mayor. After that, I was on the WIN program, which was a program put out by the welfare. At the time I was on welfare, and my little girl was about a month old. This was ’68. We got about $35 a month. They had a program they were offering you to continue your education.

I finished the course and did some volunteer work at Charity Hospital for about three days. Meanwhile I had taken the civil service exam, and I was hired after about three days of volunteer work. I worked in that position, which was a Clerk II position, for quite a few years. I was just promoted to an account clerk.

I was the youngest of two children. During my childhood days, my mother and father were separated. I remember my daddy calling us and telling my brother and me, “I got something for you and I’m going to bring it over.” We were all excited, waiting to see what it was. He brought us some membership cards in the NAACP. And I remember my mother saying, “Of all the things for him to give you, he’s going to give you this, for you to go get in trouble!” People were brainwashed into thinking, “Don’t go and cause trouble. But we begged her to let us go, and we picketed Canal Street that year. I was about 12 or 13.

I remember one time we picketed City Hall, and there was a disturbance. This minister was dragged down the steps, and they arrested all of us. I can remember my brother saying, “Let’s run.” But I was too afraid to run. I was conditioned to believe that if I ran the police would shoot me. They locked us all in the paddy wagon and took us down. We didn’t stay too long. The NAACP signed us out. But before they did I called my mother crying, “Mama, we’re in jail.” And it wasn’t too long after that that we got out. I think that gave me an early start about fighting for your rights.

Then too, my stepfather worked on the riverfront, and the riverfront has been organized for as long as I can remember.

But the main thing that got me involved, which is what makes every person get involved, was when I got on the job and got into trouble. First thing, you want some help, and the union [American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees] was there.

I had some problems with a supervisor, maybe seven years ago. I was suspended a couple of days. I went to the union. I was just a dues-paying member, I didn’t ever at that time go to union meetings or anything like that. But when I got into trouble, I went to the union, and they handled my grievance. After that, I started getting a little more involved.

I still wasn’t very, very active. Around ’76 or ’77, our union got into some financial problems. This man came in, an international staff rep, and encouraged us to get more involved. I started going to some conventions and I started going to classes for grievance handling. By ’77 I had been elected shop steward of our section.

I was real anxious for management to do something, and it didn’t take them long to do something I thought was wrong. So I tried my hand at it, and I handled a few grievances just at the first step. I started realizing I was getting a lot more respect from management. I was getting known around the job as somebody that would fight for you.

Well, finally there was an opening for chief shop steward, and I was appointed to that position. And I started handling some second- and third-step grievances.

In our local, there’s a man president and a man vice president, but these men cannot run that union without ladies. I thought about this time running for president, or trying to encourage other women to run for president, because we have a pretty decent membership, and I’m sure two-thirds of them are women. We’re doing all the work. I’ve seen times when I’ve had to handle maybe eight grievances in five days, which takes a lot of time and effort.

I think I would make a good president. I’d like to figure out some way to force management to give us even more respect. One of the things I would like to see our union do, and I would probably try to implement, is child care for working people. Even some men have to take care of their children. Our union has this nice union hall, and with a little work it could be turned into a nursery, one that would not be that expensive on working women. Women have a hard time finding somebody to keep the children. Then if you do, it’s costing you maybe a fifth of your income. And if you have more than one child, it might be even more.

When Jaliece was real young, my mother would keep her while I worked. I would hate to bring her out if she had a cold or just if the weather was bad. Sometimes she would have little plays at school, and I couldn’t go because I had to go to work. I could remember just wanting to be home in the evening with her when she came home from school. Sometimes, when I was off from work, I would bring her to school in the mornings, and I enjoyed that. And in the evenings I would walk up to the school, or if she came home, I would be there and I would always have some little refreshments.

But I had to work. And it’s pretty hard managing off of one income, especially when it’s not a very good income, and wanting some of the finer things in life. But we’ve managed. It’s still just Jaliece and myself, and we’ve always been blessed.

We managed to buy a house, and I’m really proud of that. We were living in a rented half of a double and this landlord didn’t fix anything. He raised his rent about every three months. So this particular Saturday morning there was a notice that the rent was going up $25 more, and I was just so disgusted. I got in my car and started riding around the neighborhood and said, I’m going to find me a house today. And as I was going down the street I saw a little house that had a for-sale sign in front of it. So I went and looked at it and fell in love with it. And it was in my price range. I asked the agent how much did I need. He told me $1,200. That didn’t seem so bad. I had some money saved.

We went to the mortgage company, and they told me I needed $ 1,200 more for closing costs in the bank in two weeks. So of course I didn’t have $1,200 more. But the agent was very nice, and he loaned me $ 1,000.

And I paid him back. I worked in the [Super] Dome, I swept that Dome — they were paying $3.50 an hour — many a night, after I finished working at the hospital. Sometimes it would be 10 o’clock at night, and we would get off at seven. I did what I had to do, and I raised the money. My daughter and I both sacrificed.

I don’t feel like I can get in trouble with helping employees with a grievance. That problem I had with the department head, I’m still there and he’s gone. So I don’t have that fear, and I enjoy doing it. Just this week I had a man come to me with tears in his eyes. It does something to you emotionally. Most employees, when they have a problem, they feel like they’ve been done so wrong, and they do come to you crying. And they’re crying and I’m crying, and I just know I have to try to do something to help these people.

He had a problem and we cleared it up that day. It was so ironic because this man worked in the main kitchen and our president is supervisor over the main kitchen. So he bypassed the president and came way over there to me. That made me feel good, because I knew somebody had confidence in me.

My mother used to tell me, you’re going to lose your job fighting for those other people, or that it’s dangerous work. I don’t find it that dangerous. I remember telling her people like Dr. King weren’t afraid. And you can’t live with fear. If you’re doing the right thing, you should not live in fear. And I don’t have that fear.

The Supervisor is a Jackass

Whenever there’s a problem, say for instance a suspension or what we call a letter of warning, the first step is the employee will go and see a shop steward. The shop steward interviews the grievant and talks to the supervisor and grievant together. She can also call in the chief shop steward if she doesn’t think she can handle it at the first step. If the grievant is not satisfied at the first step, then you take it to the chief shop steward, who investigates it further, and proceeds to the department head, which is the second step of the grievance procedure.

The chief shop steward takes the grievant and the department head, and you try to iron out your difference. If you still don’t get any satisfaction, you go on to the third step, which is with the director of Charity Hospital, or his designee, who is usually the hospital attorney. The third-step hearing is set up with the hospital attorney being like the judge. The union is defending the grievant, and management is prosecuting the grievant. It’s pretty much like a trial. You swear in witnesses and that sort of thing.

The hospital attorney then makes his report and his recommendation. He sends it to the director of the hospital, who approves it, all the time. If there’s no satisfaction at that step, well, then you can file for a civil service hearing. At the civil service hearing, most of the time we hire an attorney.

I can remember this one incident that happened to me on the job. I had gone in with another employee about a grievance. He was denied a merit increase. While talking to the section head about this employee’s grievance, he asked the grievant to step out of the room. Then the department head proceeded to curse me out.

Had it happened before I had gotten involved with the union I may have cursed him back. But I knew that wasn’t the way to do it. I handled it. While he was screaming and hollering - the man had completely lost his cool — I just sat there and quoted the contract.

It worked. He finally calmed down and went to praising me, and what a good employee I was, it’s just that I was too good an employee to get involved with that labor stuff, and that sort of thing. So I filed a grievance, and I had two witnesses, because my supervisor was in the room, and she was quite shocked when he proceeded to curse me out. When we got to the first level of the grievance, we went to the department head. He asked him to apologize to me for it. Well, he apologized. I didn’t accept it because about three years before this I was suspended for calling the supervisor a jackass. And here this man has cursed me ridiculously and they’re going to slap him on the hand and say, “Apologize.” Well, that’s a different standard, where supervisors are above the law and employees aren’t. And that happens a lot, I think, especially with public employees.

Anyway, I would not accept his apology. So then he told me he would write an apology. And I told him he had cursed me out in front of two employees and I was not going to accept a written apology. So then he told me he would come over and apologize in front of everybody. And I told him, no, I didn’t want that either. So he asked me what in the hell did I want. And I told him I wanted him suspended.

So of course they didn’t like that. The director of Charity Hospital and his attorney drafted up a long letter, telling me I was not in a position to tell them how to discipline their employees. They told me that they were sorry that it had happened and that it shouldn’t have happened but that I should drop my grievance because it wasn’t going to go any further anyway. But I didn’t, so we went all the way through to the third step. And at the third step, the section head was suspended. I was really proud of that. And of course he didn’t like taking the suspension, so he thought he would quit. So it was even better.

Tags

Clare Jupiter

Clare Jupiter is a former staff member of Southern Exposure. She is now a lawyer in New Orleans. (1981)

Clare Jupiter is a former staff member of Southern Exposure. She now lives in New Orleans. (1979)