This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 3, "Coastal Affair." Find more from that issue here.

Background material for this article was provided by the Haitian Refugee Center of Miami, The Miami Herald, Friends of the Haitian Refugees, NACLA, Richard Dieter of the Alderson Hospitality House in West Virginia, Roz Dixon of the Women’s Task Force for the Haitian Political Prisoners, Linus A. Hoskins of Washington International College, Max Manigat of the Caribbean Studies Department at the City College of New York and the Minority Rights Group of New York.

The South Coast’s Caribbean connection flows backward more than 200 years, as Nicholas Spitzer details in the previous article on Louisiana’s ethnic heritage. And it moves forward to the present moment, to the arrival on Southern shores of oil refined in Puerto Rico, bauxite mined in Jamaica, cocoa grown in the Dominican Republic and baseballs stitched in Haiti.

People from the islands keep arriving, too. Some bring official visas, education passes or work permits. Others, escaping chronic poverty and political repression, come with little more than the clothes on their backs.

On October 26, 1981, a 30-footlong boat, La Nativete, concluded its 800-mile trip from Haiti with 63 passengers, each taking the dangerous voyage “pour cheche lavi mouin — to search for my life.” Just off Hillsboro Beach, Florida, a powerful wave overturned La Nativete. Only 30 passengers reached shore safely. The other 33, screaming and struggling in the surf, drowned. Their bodies washed ashore while a different class of immigrants to south Florida — the wealthy retiree and seasonal visitor — watched from their beachfront balconies.

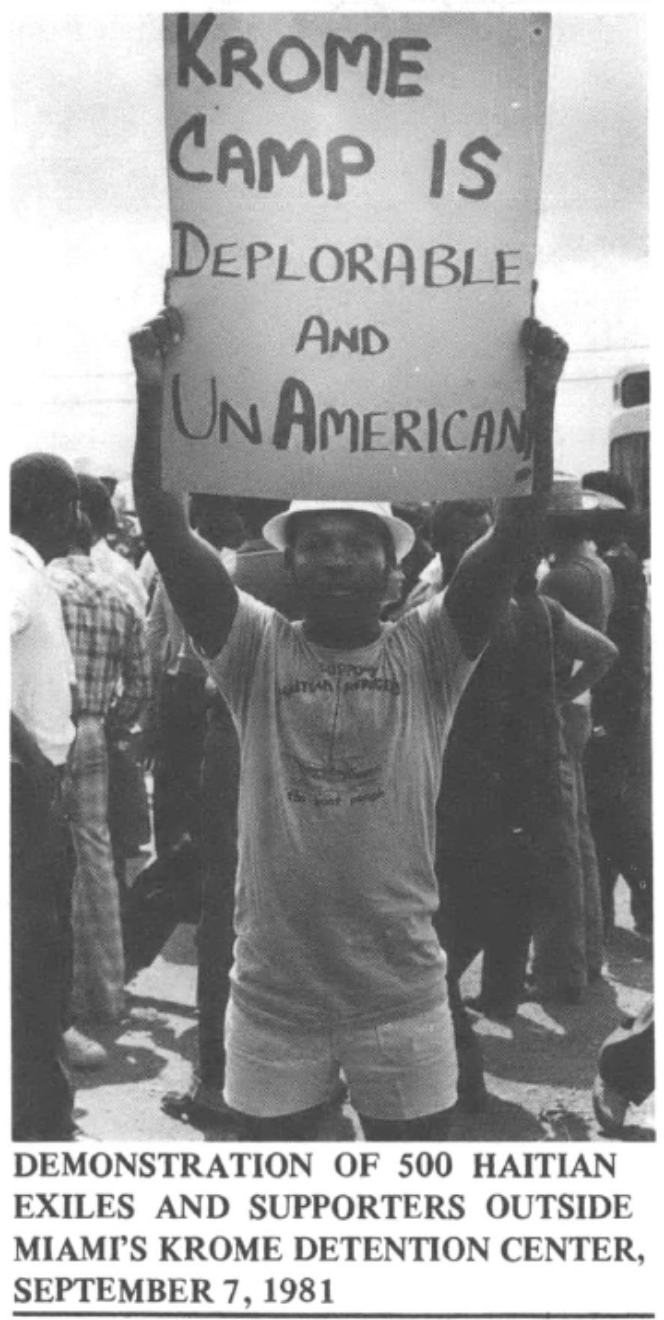

The 30 survivors received no accolades for their courageous journey or for their heroic efforts to rescue their shipmates. Instead they were rounded up and imprisoned “indefinitely” at the Krome Avenue Detention Center, an abandoned missile base located in the Everglades just west of Miami. The Haitians were seized by agents of the U.S. government not because of any crime they committed, but because of who they were. Only 28 days earlier, President Ronald Reagan had declared that “the entry of undocumented aliens arriving at the borders of the United States from the high seas is detrimental to the interests of the United States.”

The U.S. and Haitian governments had reached “an agreement,” the White House explained, whereby the U.S. Coast Guard could “interdict” and stop any suspected Haitian craft anywhere on the ocean, board it and order its return if the passengers were not properly “documented” as “refugees” — people fleeing political or religious persecution. (It was not explained what documents were sufficient to establish such status.) Any immigrants slipping through the Reagan interdiction policy would be captured on shore, if possible, and “detained indefinitely” until they could be processed for deportation or could somehow demonstrate themselves to be legitimate “refugees.”

Perhaps the passengers of La Nativete should have named their boat the Mayflower.

In the last decade, over 600,000 Haitians have left their homeland, a country the World Bank says is the poorest in the Western Hemisphere. The unemployment rate hovers at 50 percent, and on its last inspection, Amnesty International found that “the rights of free assembly, association, expression, thought and information were severely repressed.”

Jean-Claude Duvalier, Haiti’s “president for life,” rules with the unilateral control his father exercised before him. A 1979 U.S. State Department report concluded that Duvalier “wields almost all actual power . . . and significant amounts of domestic revenues usable for development continue to be diverted to personal enrichment.” Although his government salary is $25,000 per year, his personal fortune is estimated at between $200 and $500 million; meanwhile, 90 percent of the people live on less than $100 annually.

An article in the February, 1981, National Geographic says, “It is not unusual for women in the Haitian countryside to lose half of all live births to infant disease. A child of two is called, in Creole, youn ti chape — ‘a little escapee’ from death.”

Most Haitian immigrants seek refuge on the neighboring islands, which like Haiti are comprised entirely of transplants, primarily the descendants of European colonists and African slaves. Since 1972, about 50,000 Haitians have come to the United States, usually to the shores of south Florida. They might have been viewed as the latest in the unceasing wave of newcomers who have made this region — and nation — what it is today. But the hostility epitomized by Reagan’s interdiction plan reveals an official attitude and policy toward the black boatpeople of the Caribbean that contradicts everything symbolized by the imperative to welcome the “huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”

The United States cannot simply separate itself from Haiti’s history, nor pretend it has played no role in shaping the conditions in which Haitians now find themselves. The French, who gave the U.S. the Statue of Liberty, brought slavery to Haiti and developed the country as its richest colony in the 1700s. Following a 13-year struggle, the world’s first black republic was born there on January 1, 1804. But colonial economic ties with France, and increasingly with the U.S., perpetuated the island’s political instability and fostered the emergence of a complicated caste-class system.

In 1915, the U.S. Marines smashed a popular rebellion, literally crucifying its leader, Charlemagne Peralte, and killing hundreds of black peasants demanding land reform. The Marines occupied the island for the next 19 years while U.S. officials and private business leaders helped erect a more “suitable” political-economic infrastructure, including fixing the country’s currency to the U.S. dollar and removing its gold to New York.

By 1957, internal tensions had again reached such a boiling point that the U.S. allowed reformist advocate Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier to take control of the government from the French-speaking mulatto elite. In short order, however, Duvalier created his own network of merchants, government bureaucrats and feudal “judges” in rural areas. He attracted millions of dollars in international aid and investment, especially from the U.S., by projecting a new aura of stability. In reality, passivity was enforced through sheer repression, often administered by Duvalier’s private army, the notorious Tonton Macoute. Thousands of mulatto intellectuals and merchants fled the island in the 1960s, while the spiritually strong rural peasants did their best to hold on, hoping the next government would bring improvement.

When Papa Doc died in 1971, the U.S. stationed battleships offshore to ensure the peaceful transfer of power to his 19-year-old son, Jean Claude. “Baby Doc” promised land reform and new freedoms of political and private expression. But his failure to harness the Tonton Macoute or to initiate agricultural reforms soon convinced large numbers of the island’s rural peasant majority that the prospect of another 40 or more years of Duvalier rule offered no hope for a future on the island.

Serious erosion and loss of topsoil have followed decades of cutting trees for fuel and the mahogany trade; the rural ecosystem, says the Washington-based Conservation Foundation, is “ravaged nearly to exhaustion.” The prestigious Inter-American Foundation reports other factors hastening the displacement of the rural population: “Facing the very real possibility of appropriation of their land by a gros neg (“big shot”), farmers are discouraged from investing in their land, and encouraged to overwork it. There are substantiated reports of land-grabs, of judges bribed to issue competing land titles, of extortion by locally powerful, quasi-government authorities. The situation of insecure tenant arrangement is the most severe and debilitating constraint to peasant development in Haiti.”

In December, 1972, 20 months after Baby Doc took power, the first boatload of peasant families landed on the Florida coast. (They, too, were thrown in jail.) The mass exodus to other countries and to Haiti’s cities has escalated as 80,000 job-seeking youths come of age each year. Labor-intensive industries have flocked to the island because, as the Miami Herald reports, “with the lowest wage scale in the Caribbean, Haiti has become one of the most lucrative locations for industries that require a great deal of hand work.” Over 150 U.S. corporations now manufacture products on the island, taking advantage of liberal tax laws and duty fees for returning goods to the U.S.

Desperate poverty has led to sporadic revolts in the countryside, to new attempts at self-organization and support for opposition political parties — and to new levels of corruption among government officials. A few years ago, the island’s Minister of Interior concocted a scheme to sell five tons a month of Haitian blood to such U.S. companies as Dow Chemical, Cutter Laboratories and Armour Pharmaceutical. For a monthly salary of $12 apiece, 6,000 donors regularly gave their blood, considered among the richest in the world in natural antibodies because of Haiti’s high disease rates. The Minister later resigned, but others in the government have sponsored equally devious plots. In 1980, the World Council of Churches discovered that Duvalier himself receives a kickback of $70 per Haitian canecutter sent across the border to the Dominican Republic’s sugar plantations.

In late 1981, Canada suspended an $8 million follow-up grant for an aid program it had begun in 1974, because money targeted for improving health, education and agricultural services for rural Haitians inexplicably disappeared. In 1980, West Germany canceled a $32 million grant for similar reasons: corruption and lack of accountability. France has also shut off aid, and the International Monetary Fund recently banned Haiti from borrowing more money until it accounts for $20 million which “disappeared” during two months in early 1981.

Despite such mounting international censure of Haiti’s government, the United States continues to send $25 million in direct grants each year and to contribute the bulk of another $50 million that Haiti receives annually through U.S.-sponsored aid consortiums. As the principal bulwark of a regime the world community almost uniformly condemns, the U.S. government finds itself urged to apply pressure against Haiti, just as it has been urged to move against other repressive “allies” such as South Africa and El Salvador. The Miami News summed up the message in a January, 1982, editorial: “If ever there was a time when the United States was in a position to demand accountability, to dictate political, economic and human rights reforms to Jean-Claude Duvalier, that time is now. To simply encourage private, industrial investment, President Reagan’s international panacea, is to make all but inevitable the kind of revolution Reagan would least like to see. . . . Haiti doesn’t need more foreign investors taking advantage of a desperate, docile labor force to assemble purses or stitch baseballs. . . . Haiti needs to stop the medieval practice of allowing the government’s hired thugs to expropriate the land at will.”

Until the United States changes its policy toward the Haitian government, Americans in general and South Coast residents in particular can expect to see more Haitians landing on U.S. shores, working in the migrant stream along the East Coast, gravitating to Little Haiti ghettoes from Miami to New York, “yearning to breathe free,” yet — when they are caught without proper documentation — filling up U.S. prisons and detention camps.

Over 2,000 Haitians are now being held by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) in more than a dozen facilities in five states and Puerto Rico. INS procedures have changed in the 10 years since its officials imprisoned the first boatload of 65 men, women and children who reached Pompano Beach, Florida, on December 12, 1972. Attorneys for the National Emergency Civil Liberties Committee and the Haitian Refugee Center have, for example, won court decisions ordering INS to stop conducting mass deportation hearings; the Haitians’ requests for permission to live in the U.S. must now be considered one at a time, with each Haitian represented by an attorney.

But the central principle undergirding INS practice under four presidents over the last decade has remained the same: since Haiti and the United States are friends, INS assumes Haitian citizens entering U.S. borders are merely seeking economic advantage, not fleeing political persecution; as a class, Haitians cannot be considered “refugees” or “political immigrants,” but must be viewed as “economic migrants” akin to Mexicans who illegally cross the Rio Grande in search of work and who, once caught, are sent back to their homes.

The refusal of INS officials to recognize the existence of widespread political repression in Haiti, which they assume pervades communist nations like Vietnam, is considered a double standard at best and blatantly racist by dozens of human-rights organizations. Despite overwhelming evidence of Haiti’s police-state atmosphere assembled by such organizations as Amnesty International and the World Council of Churches, INS has granted political refugee status to fewer than 150 of the thousands of Haitian boatpeople whose applications it has processed. This selective blindness became all too apparent during President Carter’s “open arms and open hearts” program to grant immediate political asylum in the U.S. to thousands of Cubans fleeing “Castro’s grip.”

“It is disturbing that the government’s assumption seems to be that political persecution is automatic under a communist regime, but must be proven if the dictator is Jean-Claude Duvalier,” said Representative Walter Fauntroy, chair of the Congressional Black Caucus. It is also disturbing, Fauntroy noted, that this denial of political asylum applies to “the only group of black people who have ever sought refuge in this country.”

In July, 1980, a class action lawsuit on behalf of 4,000 Haitians brought a similar sharp rebuke of the government’s “unlawful discrimination” from Judge James King of the Miami Federal District Court: “Those Haitians who came to the United States seeking freedom and justice did not find it. Instead, they were confronted with an Immigration and Naturalization Service determined to deport them. . . . The uniform rejection of their claims demonstrated a profound ignorance, if not an intentional disregard, of the conditions in Haiti. It is beyond dispute that some Haitians will be subjected to the brutal treatment and bloody prisons . . . upon their deportation.”

An embarrassed Carter administration quickly revised INS policy, introducing a set of new classifications and rights for thousands of Haitians who entered the country during the period of the 1980 Mariel boatlift of over 120,000 Cubans. But by the end of 1980, the door to U.S. asylum and/or work permits was again closed for Haitians. And Jimmy Carter, the champion of “a foreign policy based on human rights,” had passed up his chance to award refugee status to Haitians as a group because, he told critics, he refused to be “stampeded into making an emotional decision.”

To his credit, Carter’s State Department did force a relaxing of some repressive practices in Haiti in what NACLA Reports calls “the season of free expression” from 1977 to November, 1980. Under the subtle threat of aid cutoff, Duvalier permitted more freedom of association and of the press, especially the Creole-language radio stations which in the largely illiterate nation became “the backbone of the democratic movement by simply reporting on issues relevant to people’s lives,” says NACLA Reports. But as early as one day after Ronald Reagan’s election, members of the Tonton Macoute were celebrating in the streets of Port-au-Prince, firing pistols in the air and chanting, “Cowboys are in power, now we rule over human rights.” On November 28, 1980, Duvalier initiated an unprecedented series of arrests, beginning with the imprisonment of 20 staff members of Radio Haiti and including more than 200 other journalists and leaders of labor, student, rural development, human-rights and opposition political organizations. Twenty-six of that number were later expelled by Duvalier; many of the rest are unaccounted for.

Inside the United States, President Reagan replaced INS officials who balked at new steps “designed to discourage people from coming at all,” according to David Crosland, former INS legal counsel under Carter. The steps included an August, 1981, decision to detain all new arrivals in prison without bail until their status is officially determined, a process that now takes over six months; an INS-requested court ruling (overturning an earlier decision obtained by the Haitian Refugee Center) which allowed 200 Haitians depressed by prison conditions and by the bleak prospects of obtaining asylum, to return home “voluntarily,” where they would presumably spread the word of U.S. detention practices; the September 29 interdiction executive order; and intensive publicity in Haiti of the deaths of the 33 La Nativete passengers.

In December, 1981, a State Department immigration expert boasted that the get-tough approach “has been more successful than anybody had anticipated.” He said only 1,960 Haitians had entered the U.S. illegally between August 1 and November 30, 1981, compared to 6,906 in the same four-month period in 1980.

A host of other voices roundly condemn the new measures. They include Haitian women jailed in Alderson, West Virginia, who began a hunger strike on April 2, 1982, the most recent of a long series of mass protests inside and outside the prisons; U.S. District Court Judge Robert Carter in New York, who ruled on March 5, 1982, that eight Haitians jailed in Brooklyn since July, 1981, were illegally “denied parole because they were black and/or they were Haitians;” Archbishop Edward McCarthy, who said the U.S. Catholic Conference would sponsor all 2,100 Haitians now incarcerated if the government would release them while it considered their requests for asylum; and a Haitian exile at a rally who said simply, “Our reasons for leaving our homeland are as valid as those of the Cubans, Vietnamese and Eastern Europeans.”

On the other hand, some Florida officials seem pleased with the Reagan actions because they say the state is overburdened by the medical and social-service costs associated with the Haitian and Cuban immigrants. “The whole system of resettlement in Florida has been a failure,” said Deputy Attorney General Ken Tucker. He said the entrance of more Haitians posed “a serious potential for the introduction of tuberculosis into south Florida,” and he suggested that those inside Miami’s Krome Avenue Detention Center be “carefully processed and carefully resettled — resettled outside the state of Florida.”

Ironically, Dade County and the state of Florida may have to pick up a large share of the cost of aid programs for immigrants as a result of other bold initiatives by Ronald Reagan — the federal budget cuts. In February, 1982, Vice President George Bush, who heads a cabinet-level task force on south Florida’s Crime, Drug Smuggling and Illegal Immigration, announced an extension of federal subsidies for programs serving indigent immigrants, but only until April 1. He also said, “The Secretary of Navy has authorized the use of U.S. Navy warships — I repeat, U.S. warships — to help the Coast Guard interdict ships smuggling drugs or carrying illegal aliens into Florida.”

Despite the bravado and heavy-handed measures, some Haitian exiles and immigration experts believe the boats will keep coming. “A few ships on the Windward Passage aren’t going to stop the Haitians once the trade winds shift in April,” said one refugee camp administrator. The choices Haitians face are extremely limited, he pointed out — either emigration or revolution.

“We will survive Duvalier as we survived his father,” says Miami’s Haitian Refugee Center director Father Gerard Jean-Juste. “And we will survive the Reagan administration.” Ultimately, he predicts, the Duvalier regime will be overthrown. In the meantime, coastal Southerners should expect to receive more passengers — arriving dead or alive — in boats like La Nativete.