This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 3, "Coastal Affair." Find more from that issue here.

Harris Neck, Georgia – About halfway between Savannah and Brunswick on the Georgia coast, two groups whose goals need not conflict are locked in battle over control of a tiny tract of waterfront land called Harris Neck. In one camp are the former residents of Harris Neck and their descendants, who feel they were cheated out of their land 40 years ago and now want it back. In the other camp are the United States government and a major Georgia conservation organization, who believe the land — now the Harris Neck National Wildlife Refuge — should remain a haven for rare and endangered wildlife.

The dispute is now before a federal court and Congress, but its roots go back more than 100 years to General William Tecumseh Sherman’s liberation of the Georgia and South Carolina Sea Islands and the subsequent granting of the lush, isolated coastal lands to the freed Afro-Americans (see article and profile, pages 35 and 99). While the century following the Civil War saw much of this area revert to white ownership through purchase, harassment and outright fraud, this was not the case at Harris Neck. During the decades after the war the former slaves and their descendants built a thriving community which was virtually self-sufficient: the residents fished the area’s rich shrimp and oyster resources, grew vegetables on land not permeated by salt water and operated a cannery to preserve their products for their own use and for trade with the outside world.

The approximately 100 families of Harris Neck thrived in this manner until the beginning of World War II. Many of the details of what happened to destroy their traditional style of life and set into motion the events which today pit their land claims against a refuge for wildlife are, unfortunately, lost in a morass of missing and confused documents, poor 42 memories and sometimes self-serving actions and statements.

As nearly as can be reconstructed, however, the federal government became interested in the land around Harris Neck in 1940 or ’41, when Army officers are said to have conferred with some area officials and residents, but not the black residents of Harris Neck, about the possibility of obtaining land for military uses. The officers, according to former residents, were told that those living at Harris Neck were just squatters, having no title to the land, and that the Army could have it for a song.

On December 7, 1941, a detachment of Air National Guardsmen showed up at Harris Neck, took possession of a primitive airstrip that had been built there sometime during the late 1930s and began to bulldoze the homes and other buildings of the residents preparatory to enlarging and improving the airstrip.

The residents, understandably shocked, approached the leader of the troops, a Colonel Campbell, who, according to the memories of those who were there, said that the government had passed a law condemning the land so it could be used for military purposes, but that it would be returned when the Army no longer needed it. Although the technicalities of the condemnations were not completed until 1948, the tiny community was forced to vacate immediately, with some residents — including some whites who lived in the area but who were not a part of the Harris Neck community — receiving as little as $2.44 per acre. (The top prices received at the time for contiguous land by certain white landowners is one of the “facts” presently under dispute; it may have been as much as $200 per acre.) The black residents reluctantly moved from their 2,500- acre community to an area of about 20 acres some distance inland — land with no access to the sea.

When the small Army base closed in December, 1944, the former residents of Harris Neck expected the government to allow them to return to their land. In fact, this move almost happened. The War Assets Administration, set up at the end of the war to regulate redistribution of land taken over for the war effort, ruled that the land was viable for agricultural purposes and that the former residents would be given an option to buy back the land at the price they had been paid for it.

In February of 1948, however, at the request of McIntosh County, in which the land is located, Harris Neck was reclassified from agricultural to airport use. That simple act virtually eliminated the rights of former residents; only if the federal, state and local governments all chose not to use the land as an airport would it be available to its former residents. McIntosh County officials next informed the government that they wanted the Harris Neck land for the county’s general use, but when the Civil Aviation Administration informed them that they could only use the land for an airport, the county agreed.

Blocked from returning to Harris Neck, many of the former residents struggled to continue to make a living as commercial fishers, renting dock space from several local dock owners at prices and terms that made survival difficult. Moreover, they could grow only a limited amount of crops on their 20 acres. With little hope of ever returning to their homes, many of the families began to drift away from the coast.

Meanwhile, several local landowners who, according to former residents, had been trying for years to get their hands on the Harris Neck land, signed leases with the county allowing them to graze cattle and swine there and pursue other purposes. Negotiations were begun with the Methodist Church, which wanted to use part of the land for a camp.

In the early 1950s, a few conscientious local officials sent letters of complaint to federal officials about alleged misuse of the Harris Neck property. A long string of federal inspections, memos and reports followed, establishing that the existing uses of the land were destroying or rendering worthless the runways, and that much of the federal property, including dozens of buildings, had been removed illegally.

Finally, in late 1961, the government cancelled its agreement with the county, and the land reverted to the Federal Aviation Administration, which, on May 25, 1962, turned it over to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for use as a wildlife refuge. As a wildlife refuge, Harris Neck has been a great success. Its 2,687 acres of salt marshes, open fields and stately woods shelter geese, herons, egrets, ibis, songbirds (the peak population of migratory birds in 1978 was over 150,000), along with alligators, deer and fox squirrels. It is now considered a unique national resource. But the former residents of Harris Neck and their descendants have never accepted the situation; they have always maintained that their land was stolen from them by white elected officials, landowners and bureaucrats. In 1971, with guidance from several Vietnam veterans who felt the injustice to themselves and their parents especially keenly, they formed People Organized for Equal Rights (POER). In 1972, they began writing letters to Washington and to local officials demanding their land back.

By 1976 they had interested U.S. Representative Bo Ginn in their case to the extent that he introduced a bill in Congress proposing that Harris Neck be sold back to its former owners for the price they had originally been paid for it. That bill died in committee, but in 1978 it was reintroduced, this time with the co-sponsorship of Washington, DC, Representative Walter Fauntroy.

While that bill — which eventually died — was pending, the former residents got some news that moved them to more direct action. They heard from the Army Corps of Engineers that their original dock at Harris Neck, now leased to a crabbing concern which allowed the Harris Neck fishers to use it, was about to be torn down to make room for a dock that the U.S. Department of the Interior wanted to build. Although these plans were later postponed, the former residents felt such actions could recur at any time, so they decided not to wait for the Congress but rather to take literal possession of their lands.

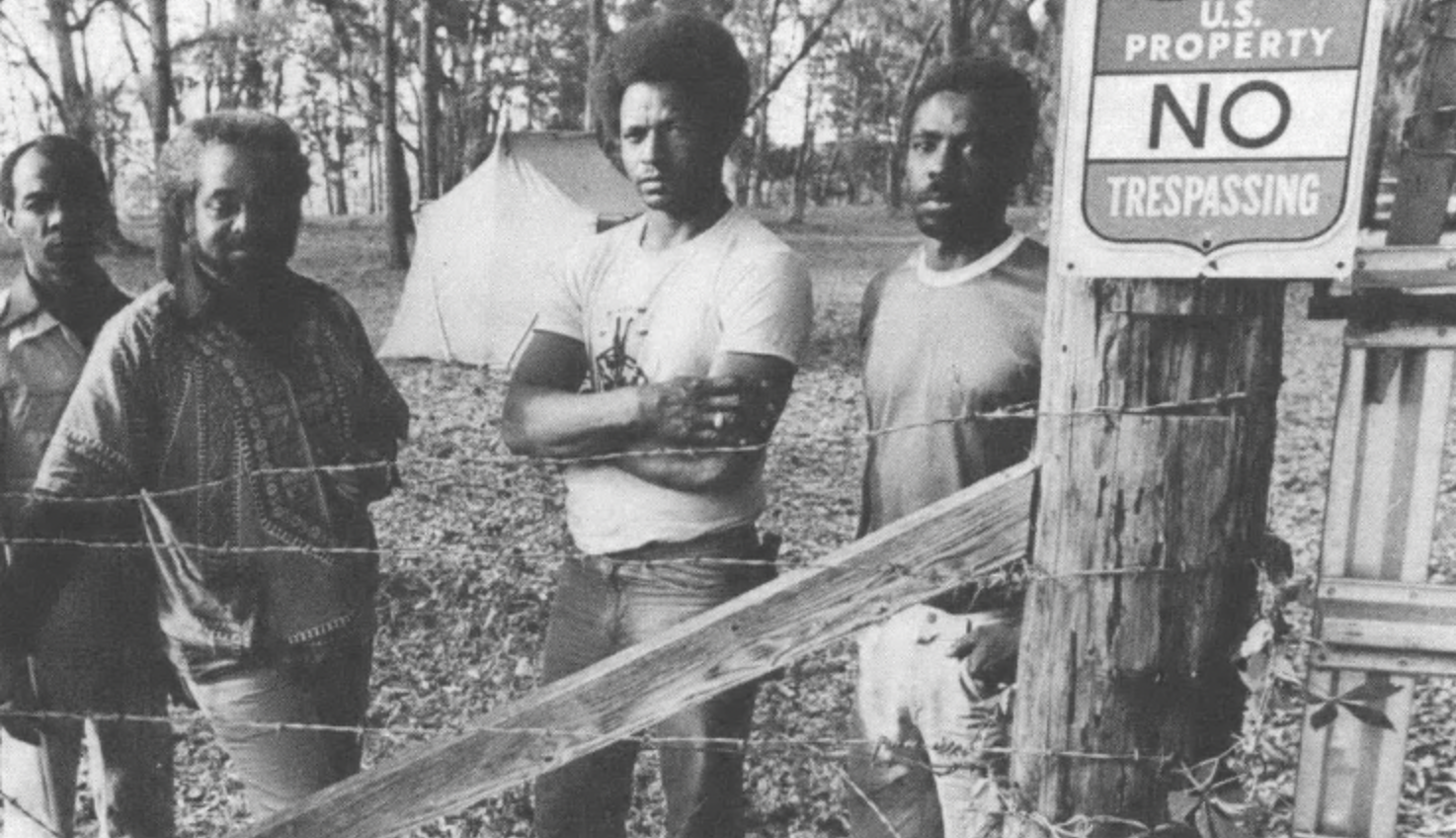

On April 27, 1979, a group of POER members moved back onto Harris Neck and erected a small tent city. Five days later, when they began trying to rebuild the old church on the property, the U.S. government brought suit in federal court in Savannah demanding their ejection from the land. They were evicted and arrested, and Judge Avant Edenfield took the case, as well as a countersuit filed by the former residents, under advisement. On May 4, 1979, he also ordered the wildlife refuge closed to the public, apparently to prevent any more of the former residents from entering the land.

In their countersuit, the former residents claimed, citing many documents and many legal precedents, that their land had been stolen from them and that they ought to be allowed to have it back. But on June 23, 1980, Judge Edenfield ruled that regardless of the value of the former residents’ legal arguments, the statute of limitations on the reversion of such lands had run out; he also ordered the land reopened to the public.

Conservation groups, particularly the well-endowed Georgia Conservancy, have also lined up against the Harris Neck residents. Hans Neuhauser, a Conservancy official from Savannah, has testified against each bill in Congress, arguing that Harris Neck is simply too valuable a wildlife refuge to lose. The organization also fears that the precedent of returning land to former residents would jeopardize other important wildlife refuges.

The rights of the members of POER and the need to retain a viable ecology are not irreconcilable, however. The Conservancy, in fact, has raised the possibility that an accommodation might be reached whereby the residents and their descendants would have special access rights at Harris Neck without destroying its usefulness as a wildlife refuge. But based on previous experience, the former residents are distrustful of all compromise proposals; they contend they have no leverage in discussions about the future use of Harris Neck until their legal right to the land is established.

And so the battle continues. A new bill, this one designed to set aside the statute of limitations in the Harris Neck case, now languishes in Congress, its fate uncertain at best. POER’s attorney, Clarence Martin of Savannah, has also appealed Judge Edenfield’s ruling to the Eleventh Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta, claiming the case ought to be argued on its merits rather than be ruled inadmissible because of the statute of limitations.

No decision has been made in the court case, but the determination of the Harris Neck survivors and heirs to reclaim their land is unshaken. “If the courts or the Congress go against us,” says Reverend Edgar Timmons of POER, “we will move back onto our land, fight for it and die on it.”

Tags

Jon Jacobs

Jon Jacobs has been active as a political organizer and journalist in the South since 1964. He has been city editor of The Great Speckled Bird, Southern Bureau chief of In These Times and is now assistant editor of Brown’s Guide to Georgia magazine. (1982)