This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 3, "Coastal Affair." Find more from that issue here.

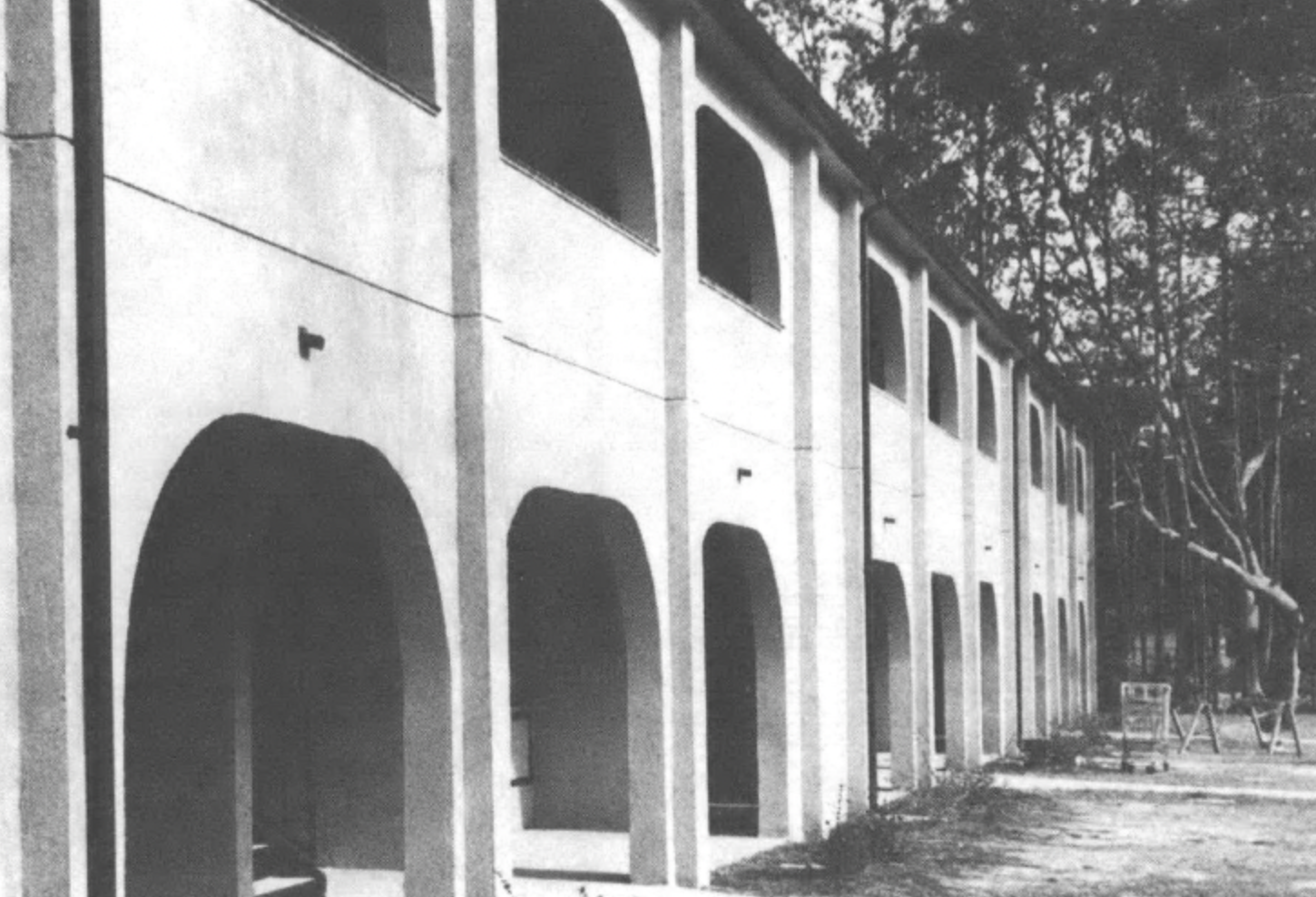

Hilton Head Island, SC - Sandalwood Terrace, the newest residential community in this sun-drenched luxury resort island, is located just across the tennis courts from The Oaks condominiums and up the road from the famous Hilton Head Plantation. An 80-unit development built in an attractive Spanish motif and carefully landscaped, Sandalwood Terrace is unique, even for an area renowned for innovation in architecture and lifestyle: it is Hilton Head Island’s first public housing project.

“There was no strong outcry against it,” says Ed Boyd, executive director of the Beaufort County housing authority. “That’s what has surprised me, that so few people have voiced their concern.”

The project’s reception was not entirely warm, however. The Oaks declined to share its access road with Sandalwood Terrace, requiring construction of an otherwise superfluous winding drive that enters U.S. 278 almost directly across from the entrance to Hilton Head Plantation. And while construction of Sandalwood Terrace was going on, the letters “KKK” were painted on a wall of the nearby Spanish Oaks villas.

This unincorporated island — 12 miles long, five miles wide and shaped like a jogging shoe — is dominated by a chain of company towns, each called a “plantation.” Sea Pines Plantation was the first, and now there are eight privileged preserves, occupying from 60 to 65 percent of the land, with names like Port Royal, Palmetto Dunes, Spanish Wells and Moss Creek. Telephone and power lines are buried underground, so as not to interfere with the canopy of live oaks, hung with Spanish moss, that cover many of the roads, lanes and paved bike and jogging paths.

In addition to the plantations, there are numerous clubs, inns, villas and condominium establishments that cater to short-term visitors. Some developments come complete with private security forces and highway access gates. The plantations are especially opulent, beautiful and at the same time a bit surreal, their artificiality creating an ambiance somewhere between Fantasy Island and a Disneyland for wealthy Wasps.

Even as Sandalwood Terrace was being completed at a cost of $3,162,772 in money from the Department of Housing and Urban Development, plans were announced for a $1 million renovation of the Harbor Town Golf Links Clubhouse and, several miles to the north, the Kuwaiti-owned development company on Kiawah Island was selling oceanfront villas for $200,000 each.

According to the Beaufort County Chamber of Commerce, about 700,000 tourists visit Hilton Head Island each year, spending from $125 to $200 per day, for a total of $170 million per year, based on an average stay of seven to 10 days. When not eating and drinking at one of the 100 restaurants, residents of the plantations and visitors to the hotels located between them spend most of their time playing golf (there are a dozen courses on the island) or tennis, fishing or just lying in the sun. Sometimes they shop at chic boutiques for designer sportswear, while company jets idle at the private airport.

Most visitors to this island would never imagine — and perhaps not want to know — that just two decades ago nearly all the residents and the majority of landowners on Hilton Head Island were black. Today, only 1,800 of the 12,500 permanent residents are black, and they own less than one fourth of the island’s land. The population turns even whiter in the peak periods — December, early spring and mid-summer — as the number of visitors swells to 40,000.

According to Emory Campbell, director of Penn Community Services, a private nonprofit education and community development organization that has been monitoring black land loss in the Sea Islands area, about 1,000 acres of black-owned land have gone over to white development in the last 15 years, “with the real crunch yet to come.”

Public housing projects like Sandalwood Terrace, Campbell says, “provide a very negative alternative. They offer cheap, convenient and attractive housing, especially for young blacks, which makes it easier for them to sell their land, rather than develop it.” The lure of quick money, he says, “enslaves a young person so they forget their community, their land, the essentials of life. They forget that a job is only a means to an end.” (See interview with Campbell on page 37.)

The comparison between the old and new plantations on Hilton Head is also apt, Campbell says, because Sandalwood Terrace “provides quarters for domestic servants” close by the condominiums and plantations.

Charles Fraser, Jr., developer of the Sea Pines and Hilton Head Plantations and the person given most credit (or blame) for opening the island to development, says, “I think the people who planned Sandalwood Terrace should be applauded. Everyone on Hilton Head is in favor of housing for people of all incomes who work here.”

Nearly all the residents of the racially mixed project work on the island, but the predominance of low-paying jobs means that even the average monthly payment of $113 for rent and utilities takes a sizable slice of their budgets.

“I’m not high on that housing project,” says Perry White, chair of the Hilton Head NAACP and a fifth-generation resident of the island. “It has the potential of creating an unprecedented ‘household class’ of black people on this island. It’s a step backwards toward greater dependency.

“Frankly,” White continues, “I’m distressed over how rapidly the lifestyle of a people has been changed in just the short span of my lifetime. From an economic standpoint, the development has been good for some black residents. But for others, it has had a relatively negative impact. And there are so many gates now.”

Tags

Mark Pinsky

Mark Pinsky is a freelance writer based in Durham, North Carolina. (1982)