This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 3, "Coastal Affair." Find more from that issue here.

Perhaps no other state depends more on its beaches as an economic lifeline than Florida, the land of surf and sun.

The state is blessed with the longest coastline in the lower 48 states. Along the 1,300 miles of coast are 750 miles of beaches, a resource which has made many a developer’s fortune and attracted untold millions of visitors and new residents. Its abundance of beaches should put Florida in good shape, considering that beaches are second only to climate as a tourist attraction.

But there’s trouble along the Florida coast. The state has not properly protected its beaches. In developed areas such as Miami Beach, St. Petersburg Beach and Panama City Beach, the natural beaches are eroding away, their disappearance hastened by buildings planted in the sand.

The beaches are victims of their own popularity. For many years, as hotels, motels and condominium buildings went up along the beach, each new structure was placed closer to the water than the one before. Waves rolling in found concrete bulkheads instead of sand dunes in their path. Gradually, wave action ate away sand from the buildings’ foundations.

When dunes are cleared away and buildings go up on the sand, the whole process of natural beach renourishment is disturbed. Just offshore, sand moves in a thin gritty stream that parallels the shore, in what is known as a littoral drift. Sand borne by this current is continually thrown ashore by waves. At the same time, wave action carries sand from the beach back to the shoreline current, to be tossed ashore again by waves further down the beach.

This shifting supply of sand is diminished by development on the beaches. When storms or rough seas wash huge quantities of sand offshore, the dunes are no longer there to provide a new supply for beach rebuilding. (Florida is more hurricane-prone than any other state. Since 1900 at least 45 hurricanes have assaulted the state’s coastline. In 1926 a storm sent waves rolling completely over the barrier island that is Miami Beach.)

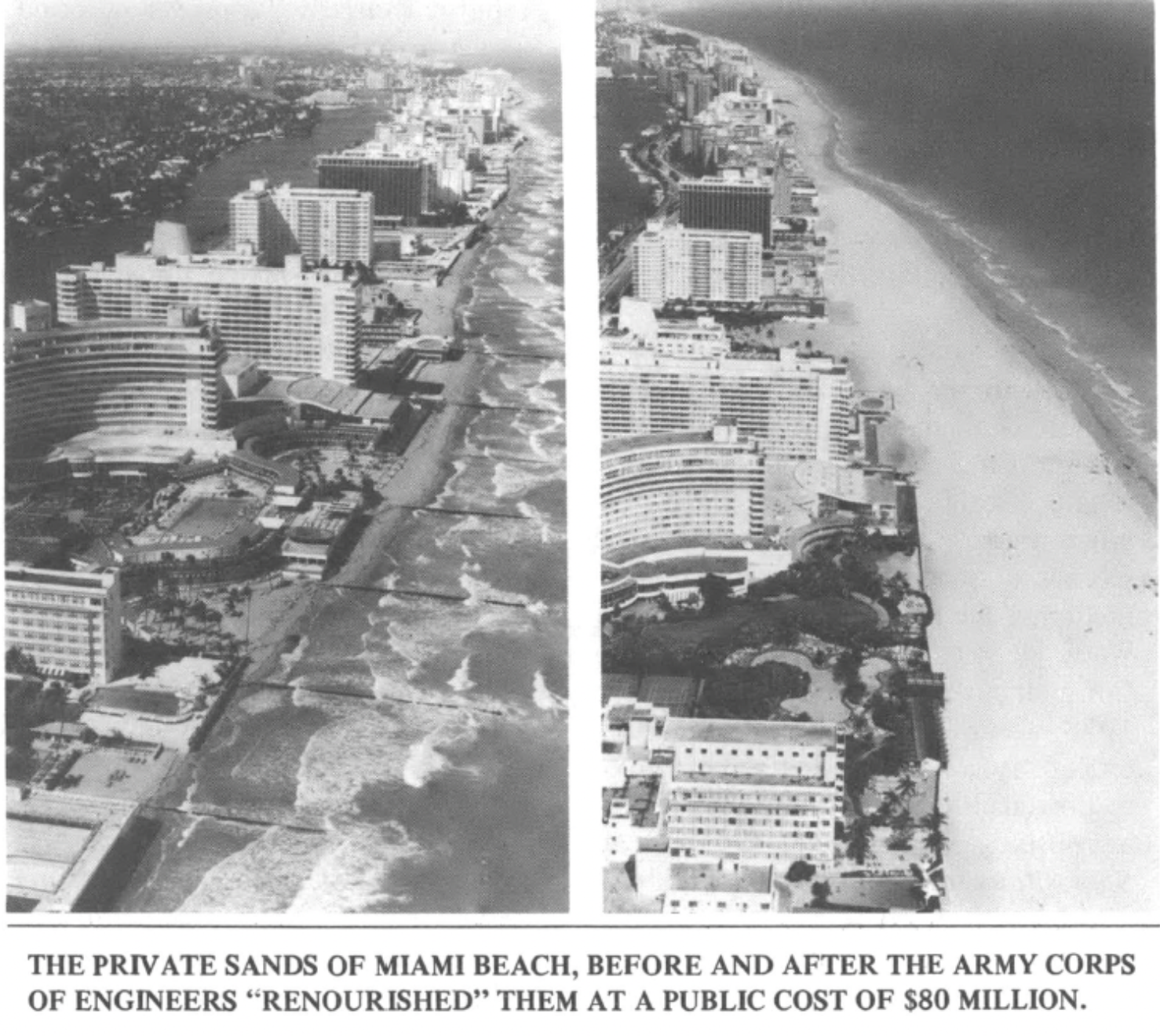

After decades of increasing oceanfront development, the cost of lost beaches became keenly apparent in the 1970s when people in the tourist industry and in beachfront communities began appealing to their elected leaders for expensive new artificial beaches. All 340 miles of Florida’s developed beaches are eroding critically. In 1982 the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is scheduled to complete the world’s largest beach renourishment project at Miami Beach, at a cost of about $80 million. Of this the federal government is paying 55 percent and state and local governments 45 percent. Yet the beach is expected to wash away in the next hurricane. Army Corps engineer Pablo Aguilera calls the new beach a “sacrificial device.”

“Better the beach wash away than the buildings wash away,” he says.

To renourish all critically eroded beaches in Florida would cost from $250 million to a billion dollars, according to Army Corps estimates. Most experts say renourishment merely buys time — at a cost of more than $1 million a mile.

“People are starting to question whether these projects are worth the cost,” says Jacob Varn, former director of the Florida Department of Environmental Regulation. “You can fight Mother Nature, but it is a very expensive battle. And who is paying for it? The taxpayers.”

Agreeing with Varn to a great extent are 95 coastal geologists who published a position paper in 1981 on engineering efforts to save beaches. They said replacing sand or building seawalls, groins and jetties is prohibitively expensive and proves futile in the end. Instead, the scientists recommended moving threatened buildings back from the shoreline and creating setback lines and conservation easements to keep structures out of areas subject to erosion. (See “Saving the American Beach: A Position Paper by Concerned Coastal Geologists,” March 27, 1981. Conveners: Dr. Orrin H. Pilkey, Jr., Duke University, and Dr. James D. Howard, Skidaway Institute of Oceanography, et al.)

Meanwhile, as buildings rise like an endless picket fence along the waterfront, both residents and tourists are finding it increasingly difficult to get to the beaches. In all the Southern coastal states except Virginia, the wet-sand beach is considered part of the public domain. Lack of public accessways and public parking areas make it impossible for the public to get to their part of the beach in developed areas where the dry sand beach is privately owned.

“The public owns the beach between high and low tide, but the catch-22 is they can’t get to it,” says Baya Harrison, Jr., a former state attorney general on environmental affairs.

When taxpayers’ money is spent to build new artificial beaches, the Army Corps is supposed to require access points every half mile. Even this rule is sometimes ignored. Along one stretch of Miami Beach where new condominium highrises run for more than a mile, there is no access to the new artificial beach. In some of the upper-income communities north of Miami Beach, few outsiders stroll the wet sand because there are no parking places within easy reach.

Where the public owns the dry sand area there is no access problem, of course. But as early as 1971, the Army Corps’ National Shoreline Study found only 166 miles of public recreation areas along Florida’s shores. By 1981, only 120 miles of Florida’s beaches were publicly owned. An additional 55 miles are in federal military installations.

Obviously the public as well as the beaches have been losing in Florida. The public’s right to the beach between low-tide and high-tide marks has been long established in Florida. One landmark court ruling (State of Florida ex rel Harry Plissner vs. Harry Simberg, Circuit Court No. 122167-D) came in 1953 in a case brought by then Miami Beach Mayor Melvin Richard and others against a hotel that had encroached on the wet sand area. Miami Circuit Judge Charles A. Carroll ruled that Miami Beach’s construction setback line was illegal because it allowed private buildings to intrude on the public domain.

The ruling was subsequently ignored and by 1968 the Parker Dorado, a new condominium building north of Miami Beach in neighboring Broward County, was able to reach 30 feet out into the surf with a bulkhead and parking garage. By 1970, the protruding bulkhead triggered such dramatic erosion to the south of it that mansions in the town of Golden Beach began to fall into the sea.

That was too much even for Florida’s pro-development legislature to take. In 1971 it passed a law requiring the cabinet to establish construction setback lines along all of Florida’s beaches. Nothing was to be built seaward of the line. But by 1978 the setback rule had been riddled by more than 600 variances. The governors and the state department heads who form the cabinet, with the power to grant setback line exceptions, routinely gave up more of the beaches to development, granting variances for projects ranging from a recreational complex including an indoor swimming pool on one beach to a miniature golf course on another.

In 1978 the embattled setback line was changed to allow for more flexibility in deciding how far back from the waves construction would be allowed. The change was based on the fact that the 50-foot setback requirement meant vastly different things on geologically differing beaches.

On the books the change seemed an improvement to some: the state Department of Natural Resources would administer the law instead of the governor and his cabinet. And DNR was given authority to grant permits for construction seaward of the line only if the project was deemed “safe” and followed certain building standards criteria. In reality, though, the change meant building on the beaches became “permittable,” because DNR had been reluctant to deny permits. Denying a permit means facing the possibility of being hauled into court and accused of “taking” private property rights from righteous, law-abiding developers.

“This is absurd,” says Dinesh Sharma, southeastern states representative for the protectionist Barrier Islands Coalition, about the permit system. “The basic legislation was to preserve and protect public beaches and to minimize losses from erosion. To allow buildings in front of the line violates both these intentions.”

Until recently, the state never made any attempt to fine anyone for illegally building on the beach. It has never pressed criminal charges or imprisoned a violator of its beach-protection laws. The state has rarely forced violators to remove structures from the beach. No official tally is kept, but the best count by the attorney general’s office is 10 times in the past 10 years.

The state has also refused to learn from its mistakes. In 1975 when Hurricane Eloise hit the Panama City Beach area in the northwest Florida panhandle, a 10-foot wall of water smashed against and damaged or destroyed more than 100 buildings, all of them seaward of the construction setback line. Most of those on the landward side of the line were not damaged. The state could have required that all new and replacement construction go behind the line. But, in almost every case, the cabinet allowed rebuilding on the original site.

As one long-time battler for beach protection, Panama City’s U.S. Representative Earl Hutto, comments, “It makes no sense to me for people to level the sand dunes which are the natural barrier against erosion, and to build these skyscrapers right next to the water, and then call on the taxpayers to pump them up some beach.”

It is politically easier to fight erosion by creating new artificial beaches than to force buildings to back up. Reluctant officials of the Florida Department of Natural Resources raise legal questions when asked why they continue to allow buildings to go up on the beach. DNR director Elton Gissendanner claims the state would have to buy the beaches if it prohibited construction on them. Not everyone agrees with Gissendanner’s position.

Barry Richard, who practiced environmental law in the state attorney general’s office before going into private practice in Tallahassee, says the law as now written “establishes a legal presumption you cannot build seaward of the line. I don’t know of any law sustaining what Gissendanner is saying.”

Back in the early 1970s, when Robert Graham was one of the conservationists’ champions in the state senate, Florida rode a brief wave of environmental protection fervor to the passage of some ambitious programs, including the Environmental Land and Water Management Act and the State Comprehensive Planning Act. But by 1978, when Graham became governor, critics say he turned his attention to powerful new allies in industry and agribusiness. In February, 1981, when Sports Illustrated published its widely quoted article, “There’s Trouble in Paradise,” which paraded the state’s environmental ills before the nation, Governor Graham was caught off guard, some say even embarrassed. With his re-election campaign underway, he was also, perhaps, worried. Still an environmentalist at heart, Graham plunged back into that arena. By the fall of 1981, he was just putting the finishing touches on a program for buying up marshlands adjacent to rivers to protect water quality when he turned his attention to the state’s troubled beaches.

“Floridians deserve to enjoy their beaches and we must move now before the coastline is obstructed by an impenetrable wall of construction,” said the governor in a much-publicized announcement of his new “Save Our Coast” program in September, 1981.

Briefly, Graham’s proposal has two thrusts: a $200 million bond issue for purchase of as much of Florida’s remaining undeveloped beaches as the money would cover (in a state where beachfront property runs about $100,000 an acre or higher), and improved legislative and administrative oversight of development practices on the coast. Outside observers and some within the state legislature are hopeful, but fear political processes already at work could undermine the best aspects of the program.

Though only court approval of the bond issue is required, the state legislature was scurrying in the spring of 1982 to pass a bill which would require legislative approval of bond issues to buy conservation and recreation lands. Underlying hostility and competition between the legislature and the governor explains this move in part; the legislators have also criticized Graham’s administration of the state’s land acquisition office which, though reasonably wealthy from oil, gas and phosphate severance taxes, has not invested its trust in new public lands and is miserably understaffed.

If indeed the legislature obtains authority over the beach bond issue, predictions about its passage are difficult to make. Many of the senators and representatives would not mind having the state purchase beaches for the public in their districts. But taking valuable land out of private hands is anathema to many of the legislators and their constituents.

In the other half of his Save Our Coast proposal, the governor has urged key state agencies to direct state and federal funds for such things as roads, bridges and sewage plants only to coastal areas that can accommodate growth. But deciding which areas cannot accommodate growth is a difficult and politically unpopular call to make.

Of the various reform bills introduced as part of the governor’s package in the 1982 session, only a few even made it out of subcommittee. The legislature’s attention was instead dominated by reapportionment — with 20 of the state’s 40 senators serving on that one committee. The only Save Our Coast bill to make headway was one cutting red tape on the use of Army Corps of Engineers’ dredged material (from harbors and inlets) to renourish eroding beaches.

Even better than anything Graham proposed was a bill drawn up by Tampa-area Representative George Sheldon, which Graham quickly embraced. It specifies numerous undeveloped islands and undeveloped parts of islands as state resources, to be protected with a stiff set of development criteria that have developers calling up their legislators and putting on the heat. Now languishing in a house subcommittee, the bill has slim chance of passage.

Generally, the legislative portion of the governor’s Save Our Coast program holds little promise until a strong coastal construction setback line is enforced by both localities and the state. A lesson in the economic facts of life might help counter the pro-development sentiment in the legislature. Florida’s beaches play a large part in luring the 35 million tourists who spend about $17 billion a year in the state. Presently there are signs that tourism may be on the decline in Florida, having slipped one percent in 1981. And Miami Beach’s oceanfront restoration was only one in what may be a series of expensive efforts to draw vacationers back again. For their own self-interest, Floridians and their lawmakers could do few better things than demand protection of their beaches.

Tags

Juanita Greene

For 26 years, Juanita Greene has reported on South Florida affairs for The Miami Herald. Three years ago she became the newspaper’s official environment writer. (1982)