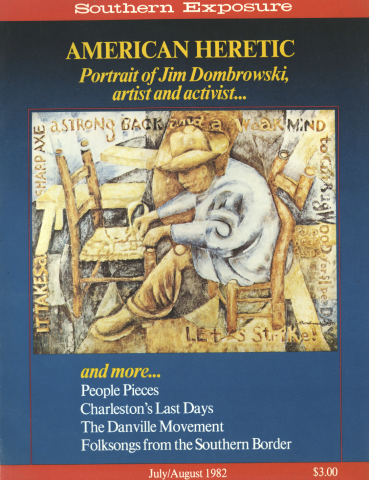

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 4, "American Heretic: Portrait of Jim Dombrowski, artist and activist." Find more from that issue here.

CHARLESTON, SOUTH CAROLINA, November 2, 1982: As a result of an accident at Charleston Naval Base today, the entire city is being evacuated to escape the effects of a radioactive cloud 28 miles long and two-and-one-half miles wide. The accident occurred when a Poseidon missile, holding 10 nuclear warheads, was being winched between the mother-ship Los Alamos and the submarine USS Holland. The winch ran free and the missile plunged 17 feet and smashed into the mother ship's side, detonating chemical explosives in the warhead.

The explosion described above has of course not occurred; and government officials claim it can't. Yet an identical accident almost happened in Holy Loch, Scotland, on November 2, 1981. According to The New Statesman, a British publication:

"The winch ran free, and the missile plunged 17 feet. Automatic brakes caught it just above the Hol land's hull. Swinging wildly, the Poseidon smashed into the mother ship's side.

"Everyone froze. 'We all thought we'd be blown away,' said an eyewitness."

The risk at Holy Loch was not so much that half of Scotland would "be blown away" in a thermonuclear explosion. The more likely catastrophe comes from the accidental detonation of LX-09, an unpredictable chemical explosive which is part of the complex triggering mechanism for warheads on many Poseidon missiles.

Unless other triggering components were also set off, the explosion of LX-09 within a Poseidon warhead would not necessarily result in a thermonuclear blast. Were the LX-09 to detonate, the radioactive material in the warhead — and in the other warheads on the ship — might not explode but would be spewed into the atmosphere in a plutonium-laden cloud which could "extend up to 28 miles," according to a 1979 U.S. Government Accounting Office estimate.

Workers or submarine crew members close to an LX-09-induced Poseidon blast would probably be killed immediately by the explosion, fire or intense radiation burns. If the detonation occurred while the submarine was in port — say, Holy Loch or Charleston — residents might be evacuated as the radioactive cloud lifted, but the land, water, plants and animals in the area where the cloud later settled would be contaminated for centuries to come. Plutonium is the most toxic substance in existence. According to Dr. Edward Radford, chair of the National Academy of Science's committee on radiation effects, the long-term effects of a plutonium-laden cloud "could be a quite serious problem from a public health standpoint."

No one knows exactly how large a risk LX-09 poses. In 1977, when the government banned the explosive from further use, it promised that all war heads would be retrofitted with a safer substance. Yet information about the progress of retrofitting is cloaked in secrecy; documents that would reveal the names and numbers of submarines with LX-09 are considered classified, and hence not available to the public.

This much is known: in 1970, 2,000 pounds of the explosive, enough to equip 400 warheads, was purchased by the U.S. government. Major General William Hoover, director of military applications for the Department of Energy, admits that "several hundred" nuclear warheads presently deployed in Poseidon submarines still contain the explosive. Poseidon subs routinely dock in Charleston, South Carolina.

AMARILLO, TEXAS, March 30, 1977 — The three Pantex Corporation assembly plant workers may never have seen a naval base, smelled sea water mixed with lube oil, or felt the cold steel of a nuclear submarine. To these laborers in bay 11-14A at the nation's only nuclear bomb factory, Charleston Naval Base was 1,000 miles and a lifetime of differences away. But inadvertently, they showed the Navy just how dangerous LX-09 could be. When one of them, following standard procedures, struck the explosive with a rubber mallet, the room exploded. He was "atomized." The other two workers died from shock.

Although all work on LX-09 stopped and the Navy soon began returning all LX-09 equipped war heads to the Pantex plant, the reason for the move was kept secret. "The truth only came to light," according to The New Statesman, "when compensation lawsuits from the Pantex victims' dependents came to trial, with disclosure of large quantities of scientific data."

"My experience in this case has made me deeply concerned about the non-safety in the production and maintenance of nuclear weapons," says Dr. Melvin Morgan, lawyer for the dead workers' families. "If the government exercises the same degree of care on board their submarines as they did in this case, then our nuclear weapons are a bigger threat to us than they are to the Russians," he says.

What if an explosion occurred in one of this submarine's nuclear weapons? It could happen in Charleston harbor.

Despite the Pantex accident, the replacement of LX-09 warheads proceeds slowly. Ironically, when a 1967 report found that 75 percent of the warheads on Polaris (pre-Poseidon) missiles would fail to detonate in combat, it took the Navy only a year to replace all the warheads.

U.S. Representative Ron Dellums has now called for a full investigation by the House Armed Services Committee into the potential health hazards posed by LX-09 in missiles located in this country and abroad. But U.S. Navy officials insist that the danger has been greatly exaggerated. According to Naval spokesperson Lt. Commander Tom Jurkowsky, the missile at Holy Loch "could not have exploded even on impact. . . . The weapon was not damaged. No one was injured, nor was there any danger of injury. There was never any possibility of explosion."

Like Dellums, many members of the British House of Commons remain unconvinced: following the accident, they demanded that the U.S. submarine fleet be withdrawn from Britain.

Few people in Charleston admit to being concerned. The assurances of safety come from the top: the admirals and generals in starched khakis and golf-course tans, whose military forebears made Charleston the nation's fourth largest Naval base. "The Navy plays a vital role in the economy of our city," says South Carolina State Representative Robert Woods. "And we play a vital role in the nation's defense."

If and when a nuclear attack comes, part of Charleston's fleet — the James Madison (SSBM 627), the John Adams (SSBM 620) and 15 other vessels — will be deep underwater, probably somewhere north of Scot land. Within eight minutes of the signal to fire, the missiles will have arched across the stratosphere and landed on their target 2,800 miles away. The LX-09 will explode in the warhead, compressing an inner core of Plutonium-239 and setting off an explosion that starts fission in the warhead's outer case of Uranium-238. Pentagon officials believe these retaliatory submarines will deter even the most ambitious Soviet leader.

Deterrents must be swift and sure to be effective. Thus, weapons makers in the early 1960s created light and fast-firing solid-fueled rockets with small, high-yield warheads. These new warheads could land within a few hundred feet of their target — a bull's eye by anybody's standards. But to be feasible, they needed a chemical explosive that had a lot of power but little bulk. LX-09 fit the bill.

Tests soon showed that in LX-09, chemists got a little more than they bargained for: plenty of power but also plenty of risk. A 1974 evaluation in which LX-09 was dropped from varying heights concluded that a dent of only half an inch in the nosecap — "consistent with a very low threshold velocity" — could produce an explosion. Full-scale detonation occurred on

one occasion when the LX-09 was dropped from only 15 inches. Following this study, the investigators listed LX-09 as one of the most dangerous plastic-bonded substances in service in 1977, warning that the compound should be handled with extreme caution.

In the actual manufacturing process, LX-09 continued to create problems. No sooner were the first Poseidon missiles off the production line than LX-09 was found to have "erratic behavior when fabricated into parts for nuclear weapons." The composition of the explosive often varied, creating a situation described by one of its developers as "drastically un stable." Alex DeVolpi, a physicist at the Argonne National Laboratory, said, "The accidental detonation of one warhead [with LX-09] will very likely propagate the non-nuclear detonation of all warheads."

Naval General William Hoover still insists that the ban of LX-09 on the heels of the Pantex explosion is "coincidence" and that those warheads that still contain LX-09 are no less safe than those that have been retrofitted with a different explosive. Adds Charleston Naval Base Captain Jim Green: "All this talk of problems is just speculation. It's like any other explosive. You don't go tossing it around."

"Good gracious, a nuclear accident could happen anywhere," says state senator B.N. Holt, Jr., who joins the chorus of Charleston officials who accept military answers almost by instinct. "The Navy is the best thing that ever happened to Charleston," Holt explains.

He has a point. After decades of a sagging economy, the rush of Pentagon dollars — especially during the 30-year tenure of U.S. Representative Mendel Rivers — earned the Navy its reputation as Charleston's savior. Its 10 facilities now employ 35,000 workers and pump $712 million into the local economy each year.

"As far as the city of Charleston and surrounding communities are concerned," says Dr. Charles Wallace, chairperson of the Charleston County Council, "the Naval Base is an integral part of the community. We're absolutely delighted to have them here. The base commander himself couldn't be a finer person. Naval people put time and effort and actual manpower into civic affairs. They're just super people."

"I've been sort of brainwashed myself," admits Jim French, a former Navy journalist who now publishes the black weekly newspaper, The Charleston Chronicle. "You never hear any public outcry. And the dangers are never discussed on television or in the papers."

Says Barbara Killigard, assistant director of federal programs for the Charleston County School District, "If we feel safe, it's because the dangers aren't brought to the attention of the public in an alarming way."

"It's a part of our daily living," adds Raymond Gadsden, chairperson of Concerned Citizens of Charleston.

"I feel pretty confident about it. They were the first industry to offer opportunities to blacks. Of course, at first, blacks were just helpers and laborers. Now they're skilled workers, doing a little bit of everything."

Charleston's love affair with the Navy is famous. The carrier Yorktown in the harbor is now a public museum of U.S. naval history.

The Reverend Samuel Price, minister at Salem Baptist Church, is less confident. "I must say, I personally wouldn't know what to do [in the event of an explosion]. There are no plans for evacuation that I know of, and it would be wise if we knew what to do before it happens." According to Ray McClain, a military and civil-rights lawyer in Charleston, "In case of an accident, there would be a terrible problem with respect to traffic congestion. There are only two bridges out of town. Every Friday afternoon, traffic gets blocked up for as long as an hour."

"People try to avoid the thought of explosion," says Bill Saunders, owner of a Charleston radio station. "It's so ugly. And in general, no one believes that there's anything they can do. But I'll tell you something. We've got to take a look, or we're doomed."

Tags

Lisa M. Krieger

Lisa Krieger is a science writer living in Washington, DC. Special thanks to Norman Solomon, who investigated the hazards of the LX-09 explosive with support from the Center for Investigative Reporting in Oakland, California, and to Thomas K. Longstreth of the Center for Defense Information. (1982)