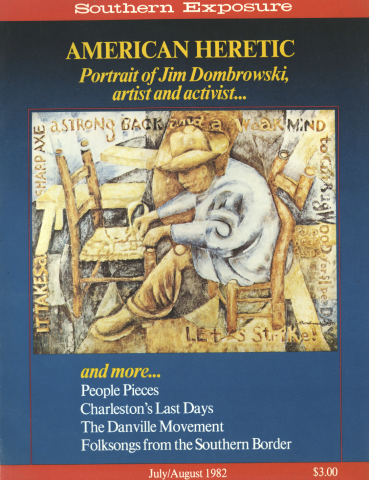

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 4, "American Heretic: Portrait of Jim Dombrowski, artist and activist." Find more from that issue here.

During the summer of 1963, the world's attention was captured by the persistent demands of black Americans for justice and equality. Throughout the South the power structure was using the laws of the Old Confederacy as well as economic coercion and brutal violence against blacks who refused to end their sit-ins, marches and demonstrations against legalized segregation.

The seeds of the Danville Movement were sown in 1960 when an NAACP youth group was expelled from the main public library by the police after staging a sit-in and using the segregated facilities. In support of the students, the NAACP brought suit and won the right for blacks to use the library.

But local elected officials and other white citizens of Danville waged a long, hard battle to keep the library closed or have it reopened on the same segregated basis. They refused to comply with the judge's order, resorting to such tactics as spreading rumors about the black attorneys to break the spirit of the black community; and reopening the library after removing all the chairs. The attorney who opposed the NAACP suit expressed the prevailing sentiment of the white community in Danville when he said, "The library is housed in the residence of Colonel Sutherlin, and served as the last capitol of the Confederacy. With these niggers in it, why, it's blasphemous!"

Although the library was eventually reopened on a desegregated basis, the "incident " involving the black students had unified the white community in opposition to blacks seeking an end to racial discrimination. Students did stage further demonstrations leading to the desegregation of the park, Woolworth's and a few other public places. But it became increasingly clear that only a massive, unified movement would have the power to overthrow the nearly 100-year reign of Jim Crow.

As the activism of the Freedom Movement grew in the '60s, many lawyers began to see the growth of a different role for their profession: to create legal buffers for and overcome legal obstacles blocking the people who were confronting long-established policies that kept blacks from participating in the economic and political life of their communities. These attorneys came to believe that, instead of winning reforms through court initiatives, they should give legal assistance to the freedom being won by the mass participation of blacks in direct action.

In Danville, a group of nationally known lawyers –- including Arthur Kinoy, William Kunstler and Len Holt — along with five local attorneys who had been active in desegregation efforts – Ruth Harvey, Harry Wood, Jerry Williams, Andrew Muse and George Woody – experienced "that fundamental shift in the role of lawyers in the area of civil rights."

In this excerpt from his forthcoming book on his years as a Movement lawyer, Arthur Kinoy describes how the legal team used the federal courts to take the weight of the Virginia legal system off the backs of Danville activists, allowing them to exercise their constitutional right to protest through public demonstrations.

And in an interview conducted by Christina Davis in Danville in 1982, Ruth Harvey Charity shares her memories of the Movement. She talks about her own involvement and about the strength and the sacrifices of the people who fought for justice in Danville. Her observations and comments are interspersed in italics throughout the text.

Arthur Kinoy:

Danville was a city of 50,000 people, at least a third of whom were black. It lies deep in southwestern Virginia, about 10 miles from the North Carolina border. The city was built along the Dan River, and its largest industry was the Dan River Mills, employing over 12,000 people, one of the largest textile mills in the South.

By 1963 the segregated society of Danville remained virtually unshaken by either the federal court orders or the beginning of protest activities. All the hotels, motels, restaurants, movie houses, hospitals, state housing projects, public schools and churches remained totally segregated. Black people were wholly relegated to menial cleaning jobs at the Dan River Mills plant. No black representative sat on a single town board or commission. Nine years after the Brown decision of the U.S. Supreme Court outlawing school segregation, Danville continued to enforce the system of white supremacy inherited from the slave society of the Old Confederacy.

Late in May the black community of Danville — inspired in part by the example of their sisters and brothers in Birmingham, Alabama, whose resistance to the fire hoses of Chief of Police Bull Connor became front page news throughout the country — made an historic leap. Under the initiative of the Danville Christian Progressive Association, a broad cross-section of the black community of Danville met and, on May 31, marched through the streets to the steps of the Municipal Building. There was overwhelming unity within the black community, and the demands their spokespeople so eloquently expressed on the city hall steps reflected the thinking of the full community regardless of past organizational differences: desegregation of public facilities; desegregation of all privately owned facilities open to the general public; equal job opportunities in public and private employment; the establishment of an official bi-racial commission; and the appointment of black representatives to all boards and commissions of the city government.

Ruth Harvey Charity:

At an Executive Board meeting of the NAACP in the spring of 1963, the discussion came up that people of Danville should be doing more to get their rights. The board meeting was being chaired by the then and present president, Dr. Doyle J. Thomas. The board discussed whether the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) or the NAACP should be contacted for guidance and direction in the Danville Movement. People decided they would make these contacts.

Reverend Alexander Dunlap became impatient with the slowness of pace, and in May of 1963 he got a number of young people and they walked down Main Street. The people laughed at them and said nothing was going to happen from that rag-a-tag bunch. Well, the next march picked up momentum.

And I tell you, when we moved, it forced the community to move. There was such unity as you have never seen before. People were putting up their homes. My parents put up everything they had to get people out of jail. And then we started to work as one to get some dignity for black folk in Danville.

Arthur Kinoy:

The May 31 march, with the united demands it presented, marked the moment of maturity in the development of what began to be known as the Movement in Danville. This concept, the Movement, was to become important to all of us in the intensive process of coming to grips with the dimensions of the role of a people's lawyer in the hectic days that followed. The Movement, as it assembled that afternoon in May on the steps of the Danville Municipal Building, belonged to no single organization, political, cultural or religious; nor was it the property of any single person, as charismatic or eloquent as she or he might be. It was a coming together of all those who were beginning to understand that only through their united strength and direct action could the long-promised objectives of equality and freedom be achieved.

The potential strength of the Danville Movement was best sensed by the power structure itself. Its reaction was swift. Ruth Harvey and Jerry Williams, two local black lawyers, sketched out what they bitterly termed the "Danville formula" for smashing the Movement. In an obviously planned and coordinated fashion, every instrument of power available to the entrenched ruling structure was used to create an atmosphere designed to intimidate and terrorize the black community.

Ruth Harvey Charity:

Let me tell you the story. A large number of young people were already involved and a few adults. The adults involved were prominent citizens and ministers. On May 31, a group assembled on the steps of City Hall and Reverend Lawrence Campbell was approached by Judge Archibald Aiken and asked to leave. When Campbell refused the Judge had him arrested for "riotous disturbing the peace and contributing to the delinquency of a minor."

Right after the march, the Commonwealth attorney drew up an injunction against Reverend Lawrence G. Campbell, Mr. Julius Adams, Arthur Pinchback, Sr., Arthur Pinchback, Jr., and Ernest Smith. What they did was make massive copies of the injunction after serving it to these principals and any other names they could get of the people involved in the marches, and all of those people were served with the injunction. In fact, before the end there were more than 600 people charged with more than 1,200 offenses.

I might add that the night Reverend Campbell was arrested, Mrs. Ida Pannil called me to ask if there was something I could do. She said, "They've arrested Elder Campbell and have put him in jail. They won't give him bond. Can't you do something?" I got on the phone and called Judge Aiken and he said, "He was just making such a disturbance that it is good for the city that he is jailed and no bail is allowed."

So that is when I really became involved in the Danville Movement. In fact, that was the real beginning. People that had been arrested were calling me to represent them and I had to be involved.

Arthur Kinoy:

Len Holt put it very bluntly when he handed us a copy of the injunction: "It has the effect of making it illegal to breathe in Danville." By the time we arrived there almost 200 people had been arrested for "violating" the injunction; the first trials were to start that Monday afternoon.

The injunction was just one prong of the legal attack on the Danville Movement. No one knew that at the very time of a meeting with Movement leaders in the mayor's office, a special grand jury had been convened a few flights above to consider possible violations of Virginia's pre-Civil War "John Brown" statute which punished "any person conspiring to incite the colored population to insurrection against the white population." When the Movement leadership met with the mayor once again the next morning, they were greeted with the astounding news that Alexander Dunlap, Lawrence Campbell and Julius Adams, three of the most respected leaders of the Danville Movement, had just been indicted under the John Brown statute. Reverend Dunlap's reaction to this news was to explode angrily, "One more meeting with those white folks and we would have been electrocuted!"

Fully armed with these sanctions of legality, on Monday, June 10 — the day that was to go down as the "Day of Infamy" — the white leaders of Danville let loose in every direction. After the failure of the negotiations with the mayor, the Movement had decided to resume demonstrations. A meeting of about 60 high school students assembled on Monday morning and marched singing and chanting down the streets toward the Municipal Building. They were led by a high school honors student, Thurmond Echols, an expert at leading cheers and group singing. When they reached the top of the steps at City Hall, they were suddenly surrounded. Waving copies of the injunction in their faces, the police grabbed Echols and two other leaders of the march and dragged them off under arrest. The others in the demonstration, frightened at this development, turned and ran down the steps into an alley which lies between City Hall and the jail where Echols and the two others had been taken.

Within minutes the police had the fire hoses out and opened them up full force. They had learned their lesson well from the Birmingham police a month before. The students, hurled to the street by the force of the water, picked themselves up and ran frantically for protection towards the black business area. The police followed them, threw them to the ground and kicked and beat them. As black people emerged from the small stores to comfort or talk to the frightened youngsters the police started to arrest them too. Over 50 people were pulled in that morning and booked for violation of the injunction.

The police had a special trap set for Thurmond Echols and his family. He was urged by the police to call his mother from the jail, and when she arrived they promptly arrested her on the charge of contributing to the delinquency of a minor. She called her husband and asked him to come and bail them both out. When he came rushing down to the jail he, too, was promptly arrested on the same charge — contributing to the delinquency of a minor.

The wholesale arrests continued all day. That evening at a mass meeting held at the Bibleway Holiness Church, people who had been beaten but had escaped arrest came to the pulpit and told what had happened. Towards the end of the meeting, Reverend Hildreth McGhee called for volunteers to go with him to take part in a prayer vigil for those in the jail. Fifty people from the church, almost all women, stood up and left the church with the minister.

Ruth Harvey Charity:

May 31 was the prelude to the June 10 march, which was the most brutal attack on the people of Danville and actually brought other people, lawyers and the eyes of the world into Danville. Reverend McGhee led a group down to the jail "to pray for our brothers and sisters." As he stood up, the order was given to "Let them have it. ''And the "Night of Infamy" happened.

You see, there was an alley between the jail and the Municipal Building [this alley has long since been closed off]. The state troopers had been called in, and they lined up to block the alley so there was no exit. The fire trucks and hoses were pulled up to the entrance, thus trapping the persons

who were there for the prayer service. When the order was given, city police, deputized garbage collectors and, I'm sure, state troopers as well, moved in against the demonstrators, beating them and turning on the hoses, washing the people down the street, like so much trash. Gloria Campbell [Reverend Campbell's wife] received such a high-intensity stream of water, it tore her dress off, and I'm sure she still suffers from the injuries sustained that night.

There were 50 demonstrators. Forty-eight of them went to the then-segregated Winslow Hospital with broken bones, fractured skulls and lacerations of every kind.

Only one white physician, Dr. Henry Borne, went to help those people. There was only one black physician, Dr. Herbert W. Harvey, and he worked all night treating these multiple injuries. I will tell you that a client of mine, when the nightsticks began to fly, hid under a car for refuge. Every time he would try to get out they would beat him with their sticks. He was severely beaten about the head.

The police denied the incident happened. They swore they knew nothing about it. There were records made at the attending hospital that somehow got lost when Winslow was closed and the records went to City Hall.

A major spin-off of the Movement was a suit filed against Memorial Hospital to integrate. I negotiated the settlement of the opening of Memorial in 1964. Winslow closed at that time.

Arthur Kinoy:

The next morning the mayor announced that 30 state troopers armed with tear gas guns and a tank had moved into Danville to assist in "maintaining order." Arrests continued throughout the black community during that day. To facilitate quick arrests, the police had mimeographed forms charging violation of the injunction.

The day after the brutal attacks in the alley, the black community responded with the largest march yet, led by well-known black minister Reverend Landell Chase. Southern black organizations committed to the civil-rights struggle — the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), SCLC and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) — responded to urgent calls by sending organizers and staff with desperately needed assistance. The major TV networks sent camera crews into town. The eyes of the country were suddenly on Danville.

Overwhelmed by the prospect of almost 200 criminal trials, the leadership of the Danville Movement called an emergency meeting between their local lawyers and the leadership of the Virginia NAACP to discover what help that organization, with its access to substantial national funds, would be in meeting the expenses of the litigation which lay ahead.

At the meeting were Reverend Campbell and Reverend Dunlap representing the Danville Movement and the five local Danville lawyers: Ruth Harvey, Harry Wood, Jerry Williams, Andrew Muse and George Woody. The delegation from the Virginia NAACP leadership included executive secretary Lester Banks and Sam Tucker, a lawyer from Norfolk, acting both in his capacity as chairman of the Virginia NAACP Legal Redress Committee and as the Virginia Representative of the powerful and wealthy NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. (The Fund, a separate entity from the NAACP, was known throughout the Civil Rights Movement as the "Inc Fund.").

Len Holt was also at the meeting together with Leo Branton, a well-known black lawyer from Los Angeles, who had just come into Danville that day with Jim Forman, one of the SNCC leaders.

When Reverend Campbell asked what help was possible, Sam Tucker answered that while he had not yet discussed the matter fully with Jack Greenberg, the head of the Inc Fund, he felt that they would underwrite all the legal expenses, whatever they would be. This seemed to be wonderfully generous and the much hoped-for offer of help. And then the underlying tensions began to show.

Reverend Campbell asked first whether the Danville Movement would have to consult with NAACP lawyers before engaging in demonstrations. Tucker's response was restrained: well, since the NAACP would be footing the bill, we would want to caution against anything unwise. Then Campbell put his finger on the most sensitive question. "What about Len?" he said. "Will he be one of the lawyers? Will the NAACP team of lawyers work with him?" Tucker's answer was simple and direct: "NAACP money can only go to NAACP lawyers and Holt is not an NAACP lawyer." The Movement leaders' response, as Len told us, and then recorded for all to see in his own account of the Danville summer, An Act of Conscience, was also simple and direct: "Len Holt, ol' Snaky [Len was affectionately called "the snake doctor" by Movement people], is the Movement lawyer. If you want to put some people here to work with him, good. Otherwise, we're sorry."

This response of the Danville leadership, faced with the enormous immediate expenses of the next week's legal proceedings, was courageous and deeply principled. The constant efforts of the NAACP leadership, both nationally and on a state level, to play down, if not discourage, mass demonstrations had led Reverend Campbell and Reverend Dunlap to leave the local NAACP branch in Danville several years before and form the Danville Christian Progressive Association, which became affiliated with SCLC. The confidence they had in Len was based not only on Len's outstanding abilities but on his deeply rooted conviction that legal talents exist to facilitate, not deter, the direct action of people in the course of struggle.

While these factors influenced the Movement leaders, fundamentally their response flowed from the need to reaffirm that the Movement was not the property of any one organization or the tool of any individual. Its policies and methods of struggle were not to be conditioned on the approval of controlling financial supporters. It was a movement of all who stood together to take effective action against the entrenched power structure. The sharp words of Reverend Campbell and Reverend Dunlap that afternoon in Danville relayed this message loud and clear. It was a message to be repeated at different critical moments by leaders of the black movement in Mississippi, in Louisiana and throughout the South whenever any group offered help with strings attached.

Ruth Harvey Charity:

There was no problem with the attorneys. All of us were associated with the NAACP. There was an attempt on the part of some people to create a problem when Len Holt came on. SCLC brought Len Holt in. In the end we would work together anyway. The greatest point of question was raised as to who was for whom, but that didn't last too long, for we all were for people.

The white power structure tried to impact on that by really trying to get something started. We were too smart for that. We knew what the Movement meant, so there was no question about power. We were together, we'd sit around the desk, on the floor, and pool our thoughts. We knew we had to beat them at their own game. And emotion was not going to beat it.

Len Holt was instrumental in feeling these situations out. He also assisted in bringing in others like Conyers, Kunstler and Kinoy.

Arthur Kinoy:

So here we all were together in Danville at Ruth Harvey and Harry Wood's office: Ruth and Harry, Jerry Williams, Len Holt, Bill Kunstler and myself and Dean Robb and Nate Conyers of the Detroit Lawyers Guild. We had all been filled in on the accelerating dynamics of the Danville formula. This last Friday the power structure had struck again to respond to the increasing militancy and unity of the Danville Movement, particularly stimulated by the leadership shown by the SNCC and CORE staffpeople who had arrived after the Day of Infamy. The city council had unanimously passed a new ordinance. All picketing, all demonstrations, all marching were illegal without a permit from the city. To make it clear that no one was exempt, as the ordinance was being announced, Len — the Movement lawyer — was arrested at City Hall for violating the injunction.

What could we do? What could we as lawyers do to help the Movement survive, to help it breathe and not choke to death, strangled by the net of legal proceedings the power structure had thrown on top of it? How would we help to counter the atmosphere of fear and intimidation which the Danville formula was designed to create?

One thing quickly emerged. No one wanted to let the city continue its offensive or for us to play out a conventional defensive role. The Movement had to fight back, and we had to find ways to assist in that objective. Before we knew it, we agreed upon the necessity for a head-on attack on Aiken's injunction, the new ordinance and the John Brown statute as illegal under the U.S. Constitution. Whether we succeeded or not, we all sensed how important it would be to the fighting morale of the Movement for us to say loudly and clearly that the Danville formula in its totality was unconstitutional, illegal and un-American.

We still had to handle the now almost 200 trials facing us, all for violation of the injunction and the new ordinance. This process alone could paralyze the Movement and generate an overwhelming atmosphere of fear throughout the whole community.

As this note was hit, I looked at Bill Kunstler. I knew what he was going to do. He reached into his briefcase and pulled out a sheet of paper, saying, "I just happen to have a draft petition to remove these cases from the state court into the federal court. It's an old Reconstruction statute we rediscovered down in Mississippi a couple of months ago. Why don't we try it here? It will stop Aiken dead."

Bill Higgs, the only white lawyer in Mississippi who had dared to become involved in the Freedom Rider cases, had literally unearthed from the dead past a federal statute which had been passed by the Reconstruction Congress back in 1866 for the purpose of protecting the newly emancipated black people. The statute was simple. Whenever anyone was threatened with a state criminal proceeding in which their equal rights would not be protected, or where anyone was being prosecuted for asserting equal rights under the federal constitution, the defendant could instantly and automatically take that case out of the state court and move it into the federal courts by the simple act of filing a piece of paper in both courts announcing the act of removal.

The removal statute had been literally buried for almost 100 years. We were going to battle to resurrect the old remedies fashioned by the Reconstruction Congress to protect the efforts of the freed black people to enforce the promise of freedom which had been made to them.

As we drafted the removal petitions that afternoon, we were responding to this urgently felt need to grasp for a legal approach which would, if only for a moment, take the weight off the backs of the Movement so that the people could resume their marches and demonstrations. We were beginning to experience a fundamental shift in the role of lawyers in the area of civil rights. Our primary responsibility was not to figure out how to create a legal mechanism to desegregate all institutions in Danville nor how to fashion a lawsuit which would fulfill the constitutional promise of freedom and equality. The black people in Danville, as all over the South, were saying that the enforcement of the legal constitutional promises would be achieved through their own direct and massive intervention in the life of their community, their city, their state and their nation. Lawyers were no longer the central agents fighting to resist the efforts of those in power to halt the forward surge of black people.

Some lawyers resisted this shift in role because it meant a rejection of the proposition that everyone, including black people, should rely primarily on the liberal sections of the business, professional and academic communities, so predominant in the Kennedy administration, to deliver on their old promises of freedom and equality. Time and again, the traditional attitude led to efforts to limit, if not discourage, the direct action methods of the Movement.

After Judge Aiken's railroading and jailing of the first Movement defendant — Ezell Barksdale, a 17-year-old high school senior who was one of the leaders of the June 10 march — the five local Danville lawyers talked with a number of the Movement leaders, including representatives of the local NAACP, and informed us all that evening that they had decided to work together with us to remove all the remaining cases to the federal court. This was an act of deepest courage on their parts. As local lawyers, they were required to appear daily before Judge Aiken in every aspect of their law practice. And tomorrow morning they were going to tell that judge that black people in Danville couldn't get a fair trial in his court.

Thus began the growth of a united team of Movement lawyers who, during the tensions and agonies of the summer, came closer and closer together. Out of this experience I once again felt the impact of that most basic lesson: the driving necessity of people's lawyers to struggle to overcome the divisive egotism of the legal profession in order to fashion a truly collective way of work. In a very rare way we began to achieve that in Danville.

To no one's surprise, Judge Aiken acted as if the federal removal law simply did not exist. When Len told him at the beginning of the Barksdale trial that he, Judge Aiken, had no power to continue the trial and that all the cases listed in the petition were now removed to federal court, the judge simply stared at him, fingered the gun he kept on his desk and said, "Let's proceed with the cases."

After the perfunctory trial, Aiken sentenced young Barksdale to 45 days in jail, denied bail and refused to stay the sentence pending any appeal. He then picked up from his desk a piece of typed paper, obviously prepared before the afternoon trial, and read an astounding statement indicating why he intended to jail all the defendants without allowing the conventional bail pending appeal. "It was," he announced, "the duty of this court to bring this riot and insurrection to a peaceful termination as quickly as possible."

After the second trial the next day, with the same results, it became strikingly clear that the only immediate hope lay in pressing hard the removal question in the federal courts. We had to press our federal actions fast or else the Danville formula, now enforced by the spectre of immediate jail for any demonstrator, might well kill the Movement.

Word came in that federal judge Thomas Jefferson Michie of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Virginia had set a date for hearing our federal motions in Danville in the federal courthouse, on the next Monday, June 24. After talking with Len and Ruth, we agreed that Bill Kunstler and I would head back to New York for two days to take care of accumulated urgent work there. We also agreed that I would start to dig into the background of the removal statute in order to develop an argument as to why its burial had been premature.

We were due to return to Danville early Sunday morning. Late Friday night Bill Kunstler called me. He said he had just gotten a call from Ruth Harvey in Danville. "You won't believe this," he said. "They've just indicted Len under the John Brown statute together with 10 more leaders of the Movement. The folks sent Len to New York when the rumors of the pending indictments began to circulate Friday morning so that they can't jail him before Monday morning. They want us back in Danville fast."

The news of the new indictments hit the Danville Movement hard. In addition to Len, leaders of SNCC — Jim Forman, Aaron Rollins and Bob Zellner — together with leaders of SCLC — Reverend Chase and Reverend Milton Reid — were indicted. This, together with the jailings under the injunction on Monday and Tuesday, was beginning to have its effect, as people in the community held back from coming to the meetings and marches. The Danville formula was taking hold of the city.

When Bill and I suggested that a good response to Len's indictment would be the formation of a formal lawyers' committee to handle all legal matters jointly, there was total, enthusiastic agreement. We set up the Danville Joint Legal Defense Committee, with Jerry Williams as director of the Committee. As our first act, we sent a telegram, signed by all of us, to U.S. Attorney General Robert Kennedy demanding immediate federal intervention to stop the prosecutions of the Danville demonstrators and their lawyers. Then we got down to work preparing for the Monday hearing.

The team, as we began to call ourselves, was expanded with a powerful contingent of lawyers from Washington, including Professor Chet Antieu of the Georgetown Law School, Shelley Bowers of the DC Bar and Phil Hirschkopf, then a third-year law student at Georgetown. Phil went out to interview the almost 50 participants in the June 10 prayer vigil to help find the most effective witnesses, and Chet and Shelley jumped into the legal preparations with the rest of us. I remember Chet picking up a copy of the town ordinance, glancing at it, and informing us all, with great dignity, that even a first-year law student could tell that this was wholly unconstitutional! "My God," I said to Bill, "who would ever dream of finding a law professor in the middle of this kind of fight?" That meeting, and working with Chet Antieu that summer in Danville, convinced me that functioning as a people's lawyer need not be wholly irreconcilable with teaching.

On Monday morning the federal courtroom was jammed with hundreds of black people. Police lined the walls. We watched carefully as Judge Michie walked into the courtroom and sat down behind the raised dais. Michie was an aristocrat and probably a millionaire. His past decisions had always been careful, always legal to the utmost, and always on the establishment side.

We knew as we prepared the hearing that our central objective had to be to use that courtroom to lay out fully and completely, for all to see, the truth about the Danville formula. The hearing in the federal court had to be a learning experience for the people of the Danville Movement themselves. It might possibly have some impact on the federal judge. But within our-

selves we knew, and we prepared the leadership of the Movement for this in the frankest way, that the chances of ultimate relief from this representative of the power structure were slim.

One of the effects of the frightening events during the past week had been to bring Sam Tucker, the chief Virginia NAACP lawyer, much closer to the Danville Movement. In a forceful presentation, he opened the case for the Movement, placing the events of the past month in a dramatic framework which set the stage for the day's proceedings. For the rest of the hearing, we carefully divided the responsibilities among the entire team. Under Harry Wood's questioning, Reverend Campbell described the entire course of fruitless negotiations with the city leading to the decision to demonstrate on May 31; the peaceful, nonviolent nature of all of the following marches and parades; the violence unleashed on the peaceful marchers by the city police.

Andrew Muse handled the testimony of Reverend Doyle Thomas, who had been the president of the local NAACP branch for the past four years. Thomas described, in full, the horrendous atmosphere of the June 17 and 18 trials. When he said quietly, "The judge was wearing a gun," you could have heard a pin drop in that courtroom. Bill took Reverend McGhee through the story of the Day of Infamy prayer vigil and Ruth Harvey conducted the questioning of Gloria Campbell, who told about the beating she had received that evening in the alley. And then, as the major witness, Len himself took the stand and brilliantly laid out the whole picture of the nature of the state court trials.

The city's case was pitiful. They produced Judge Aiken, to our astonishment, and Chief of Police McCain. They only succeeded in strengthening the picture of arrogant brutality.

At the end of the city's argument Jude Michie said, quietly, without any explanation, that he was going to "reserve decision" on the city's motion to remand the cases.

I quickly consulted with Jerry and Ruth and Len and Bill. They nodded agreement; Len's whispered comment was, "What do we have to lose?" I jumped to my feet, pointing out to Judge Michie that two of our clients, Barksdale and Smith, were being illegally held in a state jail since their cases had been properly removed to federal court before their state court trials had actually started. "We have here a federal writ of habeas corpus. We would like your honor to sign it right now, ordering our clients immediately released into your custody so that you can free them on reasonable bail."

Michie seemed a little taken aback by this request for immediate action. "But I have just told everyone I am going to reserve decisions on all the motions," he said with some annoyance. "You can't reserve this," I responded, trying hard to sound respectful. "The statute says you shall sign a federal writ of habeas corpus if a person remains in state custody after a petition for removal is filed." Quickly I looked down at the opened page of the federal statute lying on the table to reassure myself that the key word, "shall," was really there. I felt better.

Judge Michie was quiet for a moment. Then he said abruptly, "I'll talk to counsel in my chambers." In his chambers, I went over the argument again. The other Movement lawyers chimed in. All the city lawyers could say was that it was absurd, that for a federal judge to free these convicted criminals at this moment of race tension in the city would be the grossest interference with state's rights.

In making the argument as to the mandatory nature of the statute, I suppose I touched upon the deep-rooted conflict within Michie between his commitment to his own personal role as an enforcer of the federal law and the equally strong commitment to the Southern power establishment into which he was born.

The recognition of this conflict led me, without weighing any of the consequences of what might have been considered unlawyerlike conduct, to jump up, walk around the desk and, so Bill Kunstler has delightedly told people over the years, take Judge Michie's finger in my hand and place it directly on the word "shall." I said, "There it is, judge, you shall sign the writ. That's the law." We all sat quietly for a moment and then the judge lifted his pen and signed the writs of habeas corpus lying before him which would free Barksdale and Smith.

Almost too stunned to believe what had happened, we picked up the signed writs and walked quickly into the half-empty courtroom. The word spread like electricity among those Movement people who had remained waiting for news. "Barksdale and Smith are going to be freed!" You could feel the excitement in the air as people came up to us with joy in their eyes and then rushed out to spread the unbelievable news throughout the city. By the time we got to the Danville City Farm where Barksdale and Smith had been transferred as convicted prisoners, almost 50 people awaited us outside the gate. Then came the moment I never really believed would occur during the long hours of preparation and courtroom struggles. The gates opened and two men, one very young, obviously Barksdale, and one middle-aged, Smith, walked out. The broad smiles of relief on their faces as they saw us all standing waiting for them touched off a response of jubilation which was unlike anything I had experienced for many years.

That evening at the High Street Baptist Church this spirit took over as Barksdale and Smith walked into the crowded gathering. The excited responses from the audience grew as Reverend Campbell and Len Holt reported from the pulpit on the events of the day. Once again I sensed the driving necessity never to forget the critical importance of even the most limited legal victory to the fighting morale of a movement of people deep in struggle with an entrenched and powerful enemy. In that spirit the exuberant audience planned new marches and demonstrations for the days ahead in Danville.

Ruth Harvey Charity:

Arthur Kinoy is a brilliant man. He is a lawyer's lawyer when it comes to constitutional law. He was able to bring his expertise to bear at a time when we desperately needed it. We affectionately called him the "Little Professor. " He commanded great respect from all the lawyers.

Directly attributable to Kinoy's capacity to maneuver was the case when he forced the release of Ezell Barksdale, a 17-year-old involved in the June 10 march, and Harvey Smith. Both had been given active 45-day sentences by Judge Aiken after their cases had been removed to federal court. Kinoy's eloquent argument before Judge Thomas Jefferson Michie won their immediate release on June 24.

Another victory was the August 8 decision which stopped further state court trials in Danville until the question of their constitutionality could be settled. The Movement had come to a virtual standstill while people fought to stay out of jail. Even though very few of the convictions Aiken handed out were ever overturned, this decision gave mobility back to the citizens of Danville.

Marches and demonstrations continued in Danville throughout the summer of 1963 and culminated with the participation of more than 200 Danville citizens in the historic March on Washington on August 28,1963. This mass march was instrumental in the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Tags

Christina Davis

Ruth Harvey Chanty

Ruth Harvey Chanty practices law in Danville. She served on the city council from 1970 to 1974 and later ran for the senate; worked with the National Organization for Women for the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment; served as Virginia chair of the American Association of University Women and as a delegate to the International Women's Year in Houston, Texas, in 1977; and has recently organized a chapter of Black Women for Political Action. (1982)