Grandma's Divorce

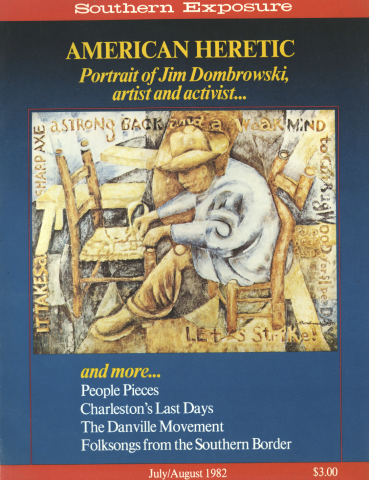

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 4, "American Heretic: Portrait of Jim Dombrowski, artist and activist." Find more from that issue here.

MIMS, FL — Grandmothers usually hold a special place in our hearts. I have three children, and I delight in holding them and telling them funny stories about their great-grandmother. They always listen with rapt attention, and often want to know, "How old were you when your grandma told you that?"

I always answer, "Well, I think I was about your age."

One story was about her childhood cotton-picking days on her family's small north Florida farm. Each child in the family was given a sack to fill during the day. But Grandma hated cotton picking, so she spent as much of the day as she could at a nearby well drinking water, until she thought her stomach would burst. Her cotton sack was never full because of these frequent "water breaks."

Grandma had a hard life, but she met her many misfortunes with courage and charity. The worst of these misfortunes was a bad marriage. Like many rural marriages back in the early part of the century, hers was more or less arranged. She knew little about my grandfather except that his wife had died a year earlier, but one Sunday afternoon in 1913, decked out in her wedding dress and flanked by her family, Chrissie May Nobles rode down the road in a wagon to be married. She was 18 years old, and beautiful, with large blue eyes and a mane of chestnut hair.

Grandma often remarked in later years on her shock at meeting her husband's family. She knew he had children, but she didn't know he had seven of them!

The couple was clearly incompatible, right from the beginning. Grandma was an easy-going woman who refused to be rushed, especially with house-keeping. She might make the beds, but neglect to sweep underneath; piles of dust on the windowsills bothered her not at all.

But Grandpa was a perfectionist, a taut, wiry, energetic man who hated disorder in any form. He was also stingy; although he had plenty of money coming in from his orange groves, Grandma had to beg for every penny and render a strict accounting of all her expenses. She received a new dress twice a year, one on her birthday and one at Christmas.

The seven stepchildren made a difficult situation even harder. They missed their mother, and deeply resented Grandpa's young, attractive wife. Any attempt on her part to discipline them resulted in complaints to their father.

My father's birth in 1916 was some comfort. Another son was born a few years later.

The pitiful marriage went from bad to worse. Grandpa demanded to know why the meals weren't grander, the house cleaner, the children more disciplined. Grandma rared back: how could the meals be grander when he was so tight with money? As for the house, she had nine children to clean up after; and by this time she had given up on trying to control the stepchildren.

Finally, in 1922, after a hair-raising fight over money, Grandma threw in the towel. Taking her younger son by the hand, she started down the road towards her mother's house. Grandpa ran after her, begging her to come back.

"Chrissie," he pleaded, "I'll put a thousand dollars in the bank in your name."

Grandma hesitated. She turned and gave him a long soul-searching look. Finally she answered, "No, damn it. I've had it."

And so she had. She returned once, to collect my father and her few belongings. She moved in with her parents until the long, bitter divorce was over. Then, with the money granted by the settlement, Grandma bought a small white frame house just off the highway in Mims, Florida.

Back in those days, a divorce was as rare and as scandalous as a hanging. In that small, Southern Baptist community, divorced women were treated as little better than prostitutes. Former women friends crossed the street to avoid speaking to Grandma — despite the fact that she led a scrupulously upright life, banning hard liquor from her house and allowing no men inside except for close relatives.

The Depression hit Grandma and her two sons hard. By this time her settlement money was spent and she received no child support payments or alimony. Thanks to ingenuity and a small garden, she managed to keep plenty of food on the table, but clothing posed a real challenge. My father tells of standing in the corner of a room watching Grandma cut up one of their few remaining sheets to make a dress. Eventually Grandma got a job making prison uniforms; later she went into nursing and companion work for elderly people.

As the years passed, Grandma lived down the stigma of having been divorced, but she never forgot what she had been through. Several times she took in divorced women and their children, and helped them rebuild their lives. But she seemed to hold no grudges, and when she died most of the town turned out for her funeral — including the stepchildren who had opposed her so bitterly.

Grandma was a woman ahead of her time. She had the guts to get out of a bad marriage, when divorce was almost unheard of. She bore up under all the gossip and abuse, when many other women would have gone insane or committed suicide. I'm proud to be able to tell my children about such a remarkable ancestor.

Tags

Carolyn Hanna

Freelance, Summerville, SC (1982)