This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 5, "Prevailing Voices: Stories of Triumph and Survival." Find more from that issue here.

Highlander Center, the residential school that cultivates the special power of adults learning from each other, is 50 years old this October. Now located in New Market, Tennessee, the school worked with the young CIO unions in the 1930s and ’40s, with the nascent Civil Rights Movement in the 195.0s and ’60s and with the blossoming of Appalachian activism in the ’70s and into the present.

To help celebrate its fiftieth birthday, Highlander board member and Foxfire editor Eliot Wigginton joined Sue Thrasher of the Highlander staff in preparing a book which Doubleday agreed to publish, sight unseen, with the royalties to help in some small way Highlander’s work over the next 50 years. The book, to appear in the fall of 1983, is composed of lengthy interviews — most of which were done specifically for this book — with some 30 individuals who, at some point in their lives, had some contact with the school. Interviews with the cofounders, Myles Horton and Don West, were included, of course. So were interviews with early staff members and friends like Ralph Tefferteller and Zilla Hawes Daniel and May Justus. And so were interviews with labor, civil-rights and Appalachian activists like Ralph Helstein, Lucille Thornburg, Studs Terkel, Pete Seeger, Julian Bond, Andrew Young, Rosa Parks, Marion Berry, E.D. Nixon, Edith Easterling, Sue Kobak and Hazel Dickens.

“They are all people,” says Wigginton, “with their figurative sleeves rolled up who are still trying to make a positive difference in a confusing and often threatening world.”

Asked to characterize the book, Wigginton wrote: “I’m too close to the project at this moment to be able to judge objectively. I think it’s a good book, though. Good and solid and decent and basically hopeful. Like the school whose work it celebrates.”

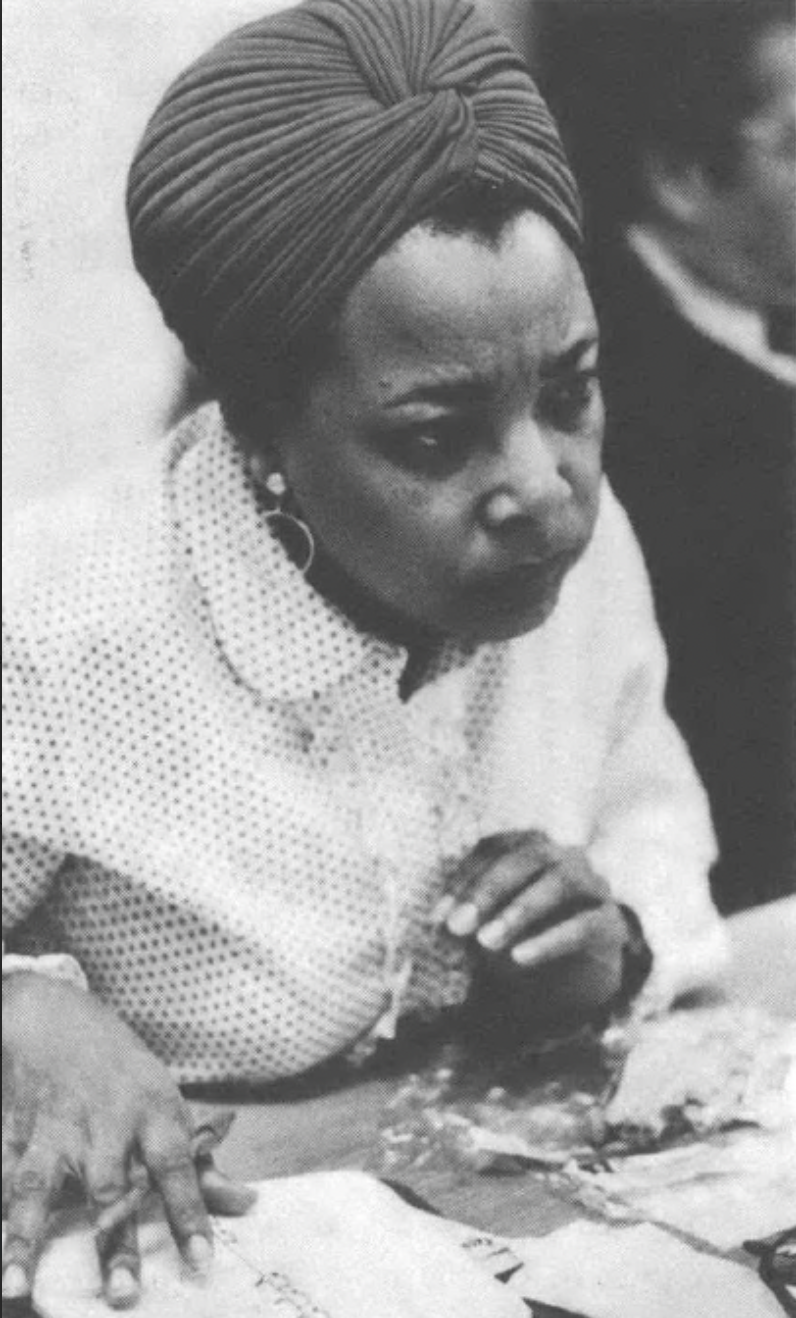

Dorothy Cotton is one of those with her sleeves still rolled up. She was among a handful of people who plunged into work with Martin Luther King, Jr., in the earliest days of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). And she continues to give many of us guidance through her work at the Martin Luther King Center for Social Change in Atlanta.

Cotton grew up in Goldsboro, North Carolina, where her father worked in a tobacco warehouse. After high school, she went off to college in Petersburg, Virginia, and was quickly drawn into the Civil Rights Movement. She has been involved ever since — between her days with SCLC and the present, she directed a Headstart program in Birmingham, managed social services for the city of Atlanta in the mid-’70s and was regional director of ACTION from 1978 to ’81. She recently sat down with Eliot Wigginton and Sue Thrasher to record her memories of the ’60s and her hopes for the future.

Dorothy Cotton: There was a preacher in our town, his name was Wyatt Tee Walker. Wyatt was the Baptist preacher at the Gilfield Baptist Church in Petersburg, Virginia, and I was a member of his church. I was in college there at Virginia State College, and a lot of us flocked to his church. He was this young, handsome, dynamic preacher; and in those days everybody got all dressed up to go to church, you know, hats and gloves. You know how we used to do.

We went to hear him preach and really got involved in the church. He was one of those preachers who dared to take the gospel to the streets. In other words, to live it. Well, black folk could not use the public library — if you can believe that — because the public library was housed in some building that had been given by some family, and the excuse the town fathers gave (and it probably literally was the town fathers in that day) was that in the will it was left for the white folks.

So Wyatt looked at this library situation and said, “We cannot have that.” He asked the national NAACP to help us make a case and take it through the courts, but they had too many cases at the time. So Wyatt, being the renegade or whatever he was, said, “We will protest here locally.” He formed the Petersburg Improvement Association, which was a take-off on the Montgomery Improvement Association. This was in the late ’50s, and Wyatt used to say I was kind of his right arm, since I was secretary to the association.

Anyway, we began trying to integrate the public library. Then we moved from the library to the dimestore where they had a lunch counter for whites only. I don’t think I knew consciously what I was getting into; I remember walking with a picket sign one day at the dimestore, and this elderly black man said, “Why don’t you stop all this mess out here in the street?” You know, we were six or seven folks picketing, and the folk up on the hill were wishing we would stop all that “foolishness in the street.” And then this man said to me, “Lady, ain’t you got a table at home?” I remember putting my picket sign down and going to talk to this man: “Look, mister, if your wife were down 26 here shopping and she wanted to have a cup of coffee at this lunch counter, do you realize she would have to go all the way home? Don’t you feel she has a right to have a cup of coffee here also?” So I’m convincing this black man on the sidewalk, but I was really convincing myself that the cause was right.

So we were doing some interesting things in Petersburg. Then Reverend Walker met Dr. King somewhere in his travels and invited Dr. King to come to Petersburg to speak. Dr. King liked what Wyatt was doing with us in the Movement, and he asked Wyatt to come to Atlanta to help him formulate the Southern Christian Leadership Conference [SCLC].

Wyatt said, “I will come if I can bring the two folk who helped me most here.” And that was a fellow named Jim Wood, who is dead now, and myself. I was working during the summers to finish my master’s degree in speech therapy at Boston University, but I said to Wyatt, “Well, I’ll go down for about six months” — and that was 20 years ago!

So I came to Atlanta to work with Dr. King and Wyatt Walker. At that time we were about five folk; of course we grew into the hundreds as the various campaigns happened, but when we came in 1960 to Atlanta, we certainly didn’t know the Movement would take the turn that it took. There was no way we could have known then of its eventual scope, size, importance.

Even those of us who were so intimately involved with Dr. King, I think, didn’t realize what we were in. If we had, we would have had tape recorders. When we were driving along with Dr. King in the car he would have these great and fun philosophical discussions, arguing with Andy Young on some theological point. If I had only had sense enough, I could have had 10 books filled with just fantastic discussions. His humor in all of it, and the way he could recall all of the philosophers and theologians and how they counterpointed. I was just really enthralled by it all.

In those early days of SCLC, we heard about a Citizenship Training Program at Highlander, and early in 1961 I went to a Highlander workshop at Monteagle, Tennessee — my first visit. Myles Horton knew Highlander’s “demise” — at least in Monteagle — was imminent,* but the Field Foundation was still willing to fund the Citizenship Schools, so another place for that program was needed. So SCLC got the program from Highlander, and we spread it around all of the Southern and border states.

Luckily we were able to get the people who were with it initially at Highlander — Septima Clark and Bernice Robinson. Andy Young was the director, and I was called the educational consultant, and Septima was a teaching specialist. I heard Andy say one time that the Citizenship Schools really were the base upon which the whole Civil Rights Movement was built, and that’s probably very much true. I can hardly think of an area of the South from which we did not bring a group of folk — I mean busloads of folk, sometimes 70 people — who would live together for five days, and we did it! We had fantastic sessions!

For five days we’d work with people we had recruited, some of whom were just off the farms. like Fannie Lou Hamer, who stood up and said, “I live on Mr. Marlowe’s plantation.” And talked about how Pap, her husband, had to take her to the next county because they were going to beat up Pap and her if she didn’t stop that voter registration talk. She stood up and talked about that and taught us the old songs they sang in the meetings to keep their spirits up. You know, we sang a lot in the workshops then.

Was the main thrust of the Citizenship Schools, after they went to SCLC, still teaching people reading and voter registration and basic skills of that sort?

Dorothy Cotton: Oh yes. The very basic stuff. And, of course, we learned that from Septima and Bernice, and the Highlander folk. We kept the same model and probably expanded it some. I remember a session that I did on “How to Teach,” because we were trying to make teachers out of these people who could barely read and write. But they could teach, you know. They could teach. If they could read at all, we could teach them that c-o-n-s-t-i-t-u-t-i-o-n spells constitution. And we’d have a grand discussion all morning about what the constitution was. We used a very non-directive approach. You know: “What is it?” And after an hour’s discussion, we would finally come to a consensus that it was the supreme law of the land.

Then we’d start talking about parts of that document. And, of course, we’d get very quickly to the “Fourteenth A-m-e-n-d-m-e-n-t spells amendment, and the Fourteenth one says what? And what makes you a citizen?” People would say, “You are a child of God” — because we come from the Bible Belt, right? Or people would say things like, “If you register to vote, you are a citizen.” But before the session was over, we would know that all persons born or naturalized in the United States are citizens, and they would learn that, and we’d write that.

That’s what they were learning to read and write — and the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and the fact that no state can take away your privileges. And then we would translate that into this grand discussion about the fact that Governor Wallace cannot tell you that you cannot march down Highway 80, or whatever. And we would say, “Well, you see when you go home, rather than just throw out answers or speeches to people, how much better it is to discuss with them what they need to know.”

So then the folks went home and worked in voter registration drives and went down to demonstrate. You know, it was Miss Topsy Eubanks — I quote her all the time — who said in a workshop in Dorchester,* “I feel like I’ve been born again!” And she was probably 60 years old then. She went back to Macon and was seen sitting in the courthouse as a poll watcher. She’d never thought of herself as being that before. But demonstrations grew up around people. The enlightenment that happened for them there in Dorchester became a flowing out from that experience.

One woman told me she had argued with her son, who was involved in the demonstrations, trying to get him out of that “mess in the street.” And he started asking her questions, like, “Do you feel it’s right for you to be treated the way you’re treated, and for black DOROTHY COTTON folk to only get jobs pushing brooms?” And, “Do you feel it’s right just to be a second-class citizen and have to sit in the back of the bus?” And she said, “And the cobwebs commenced a-movin from my brain!”

So the cobwebs “commenced a-movin” from a whole lot of folk’s brains. And they went home on Friday, and they didn’t take it anymore. They started their little citizenship classes discussing the issues and problems in their own towns. “How come the pavement stops where the black folk section begins?” Asking questions like that, and knowing whom to go to talk to about that, or where to protest it.

Eventually, in later years, the so-called black militants — you know, the guys who were black power with the fists and the berets and the jackets and the boots — they started coming to Dorchester also. They came in cussin us out, telling us we were against the f—g revolution, and if you want a new school system burn down the f—g building and “off’ the superintendent.

We somehow — thank you, Father — had the sense to say things like, “Well, if you gonna burn down a school, do you know how to build one?” And, of course, they didn’t have any answer to that. “If you gonna blow up the bridge, which one of you is an engineer? Do you know how to build one back? If you gonna burn down that factory, you better first talk to Miss Lucy over there. Her husband works there, and that income is their livelihood. Now if you burn down the factory, Miss Lucy will kill you.”

We finally got them to do some of the activities, like the trust walks. We said, “You take Miss Lucy on a walk through the grounds out here, and when you come back, you tell us what she said.” Of course, we had to do that more than once cause they came back not telling us what she said, but what they said to her. “But did you listen to what she said and what she wanted?” If you want to have change, of course, the bottom line is that the folk for whom the change is meant must be involved in it.

How were decisions made at the staff level in SCLC?

Dorothy Cotton: It was interesting how Dr. King worked with his staff; he relied on them a great deal. I’ve never known another situation where people worked with someone who was at one time the “boss” and who was also their “friend” and someone they genuinely loved being with. We were relaxed and casual, and yet we could go into some serious, heavy sessions.

Like the Good Friday that Dr. King went to jail. I’ll never forget. We were sitting in Room 30 at the A.G. Gaston Motel in Birmingham, Alabama. We sat in that room for what seemed like 24 hours debating what we should do next. The demonstrations were at their height with the dogs and the fire hoses in Kelly Ingram Park and all of the marches, and we were all strategizing. And some of the little middle-class ladies were hiding away in a corner making picket signs for us and driving us in their fancy cars through back ways to get us downtown onto the main streets.

The whole town was really kind of at a standstill, and the momentum was just great. And so many people had been arrested. There must have been 3,000 students in jail. I’m not sure of the numbers, but the schools were virtually closed down because so many students were locked up.

The leaders, of course, were the first to go to jail. And we sat in that room debating whether Dr. King should now lead the next march, because surely he would be arrested. We debated notions like, “Dr. King should stay out of jail because we need him to travel around the country now to raise bail money for the other folk who are in jail.” Dr. King eventually stood up and put on his overall jacket and didn’t say a word. But we knew that the decision was made and that he was going to go. We made a circle in the room and sang, “We Shall Overcome,” and he just went upstairs, and he didn’t say anything. That’s how decisions got made, I guess. He listened to all the deliberations, you know. He listened to all the deliberations.

Is that the kind of quality that makes a leader? Someone who really listens to what you have to say, who isn’t really separated from you in terms of status, someone who’s inspiring?

Dorothy Cotton: It’s so elusive. Was it the times? Was it the situation? Was it the fact that he inspired hope in people who had no hope, and he knew that they needed that most at that time? Was it that he defined the issues so clearly for people? Was it that he articulated so well the issues and the goals?

Deep down in ourselves we knew that we needed to change things, but Dr. King said it — he articulated it. You know, when Rosa Parks wouldn’t get up from her seat, he could interpret that for people, and then people quietly within themselves could say, “Oh, yes. I ain’t gonna take this no more,” and start to feel that they wouldn’t take it and therefore would walk instead of riding the buses.

And he projected where we could go with the Movement. He kept saying, “My people will get there.” And we felt that he had a vision of where “there” was. “I may not get there with you, but my people will get there.”

[A large portion of our interview was devoted to Dorothy Cotton’s feelings about young people and about education for future action - where do we go from here?]

Dorothy Cotton: People should not be separated by color. Color is an artificial barrier. My brown skin is not what makes me. It’s the totality of my experience that makes me. Ideally, I would never refer to you as white and me as black. Ideally. I believe ultimately, when the Kingdom comes, we will all have learned how to live together and work together on common problems and issues that we see. The superficial divisions will disappear. I think color just divides people, and ultimately that is what wars are fought over. Even movements will have to learn that we are all made in the same image.

I had a conversation with a 13- year-old boy who lives next door to me about two weeks ago. He dropped out of school, and it took him about two weeks before he could admit it to me. I had been challenging him since his mother died: “Hey, John, you might be the next mayor of this town.” I just felt he needed some encouragement. But he said something that made me feel so sad: “Well, you can’t be nobody if you ain’t already somebody.” When he said that to me I really kind of stood there. I gave him a spiel, and yet I walked on up my driveway feeling really helpless.

I started asking myself, “What happens in the classroom?” And that caused me to reflect on what happened to me. I lived in what we called a shotgun house - a shack, you know — where you looked in the front door right out the back with the outhouse in back and all of that. I don’t remember any books in my house or even a newspaper, and there was nobody in my family or on my block that I knew about that had gone to college, but somehow I knew I was going to college.

There was a teacher that helped motivate and inspire me, and I really will never forget Miss Rosa Gray, who was the high school English teacher and drama coach. One day I had to do something in class — some speech or performance — and she said, as I finished, “There’s your ready-girl.” I still remember when Miss Gray said that. It gave me something to start to live up to. Then, somehow, I got to be the lead person in all of the plays in high school, and I just really felt close to her. I felt like a leader with her and because of her, and I then sort of played that role. Right on through college I got into leadership positions.

I felt close to Rosa Gray. She was very special to me. Who is special to that 13-year-old next to me? What teacher became special to him? I think with both parents and teachers there’s a big cop-out going on. It’s like we’re scared of kids. Parents are scared of their own children. Teachers are afraid of them. Who is close to anybody? We have gotten afraid of it. Children need the touching physically and mentally and emotionally and spiritually. Uplifting them, inspiring them, taking an interest in them. I think there’s a real lack, and we need to learn how to do that again.

Everything’s out of control now! You think of every area of your life, and you feel like somebody else or something else controls it and has the power over it. Not you! Your health care, your education.... That boy who is my neighbor feels helpless. He has no sense of power, himself. He doesn’t feel like he’s anybody. And he feels no ability to change his situation. I think the schools could help him first learn how to observe the situation in which he finds himself, and then to know that he does have some power.

It’s almost like we have to do Citizenship Schools everywhere because that kind of thing is what we learn: who the mayor is, what his duties and powers are, how he got there in the first place, and learning that you have something to say about who he or she is. You have something to say about that, and you have something to say about your livelihood, your lifestyle, public policy. I learned more about civics when I was teaching and running the citizenship schools than I ever did in any civics class in school. Today young people don’t know how all that happened.

We are to blame for that because we didn’t teach them what we did. We didn’t teach them how Dr. King made a decision to take an action. We have not described these actions to them. You know, we didn’t just jump out into the streets and march. I mean a lot of things happened before we marched, sometimes sitting up, not only all night, but for days in retreats agonizing over an issue before we acted.

Now, I have gotten invited to speak on some college campuses. I can go in and do my speech, and I ask myself: “How can I make them feel, feel what we went through?” when they never saw any “white only” signs or lynchings, and I know that some of them can really get with me. I mean, I can sing an old song like, “I’ve been in the storm so long, I’ve been in the storm so long, children, I’ve been in the storm so long, Give me a little time to pray.” And I look up, and they’re crying, and so am I. I tell em what the storm was, that they had to pick the cotton before the sun went down or go back to slavery, and I always intersperse some of the old songs with the talking about it. And I know now I do that to help them feel rather than be intellectual about it — to feel what it was then — which enhances their need to know and experience what we went through.

Now one problem is to help them see what has to be done next. I don’t think they even have clear goals, and I don’t think kids know how to analyze the problems and to see what issues there are. I think we haven’t helped them to see what the next issues are.

Help me to see what the next issues are. During the generation when all this was happening, things were a good deal more clear-cut - I mean, you could only eat at certain kinds of restaurants; you could only stay in certain kinds of motels; you had separate waiting rooms for trains and interstate buses. Is it harder today?

Dorothy Cotton: I think in a way what we need is simple. It may be so simple that we cannot grasp it, because we are so used to complicated issues. First of all, I’d probably help young people focus on what kind of world they want to live in. I don’t think it takes a long time to learn that an over-involvement with material consumption is not fulfilling. I’d like to talk to folk about what material things they want to get, but also to “seek ye first the Kingdom,” because even after you get the things, you will find an emptiness there.

We are not used to looking at what life is all about. We don’t know what life ought to be about or what the good life really is. If we focused on that, then we could start to look at what causes it to happen. I really think that we are searching for something we wouldn’t even recognize if we found it, because we haven’t taken the time to think about it.

To me, it is knowing why I am here in the universe at all. I think I know. Would you believe it? I think I know. I have at this point a feeling and interpretation and understanding of what God is: a spiritual force in the universe. And somehow I am a manifestation of that force — as I think we all are — and we are here to fulfill the purpose of that great spirit. What we have to do is simply relax and be open to the flow of that spirit within us. Does that make sense to you? To be open to it? I think if we are, then we start to feel attuned to all growing things and to life itself. Life is a force that flows and connects us all.

For self-satisfaction and for pleasure? So that you become an agent by which it gets extended to other people? So that your purpose becomes to make the world better?

Dorothy Cotton: Would you believe all these things happen? Number one, it is pleasurable, because one does start to feel peaceful and that’s a pleasurable feeling. Also, one does impact other lives because people feel that kinship and that at-one-ment, if you will. You start to relate to people in a different way, and you impact other people’s lives in a very positive way. I could go back to the Scriptures at this point, and talk about the “peace that passes understanding.” It’s not something that one knows intellectually; you just know that one can be peaceful about life, and then you start to fulfill whatever the divine plan is for your life. You make all kinds of things happen, and if everybody knows this, then the whole world is better.

I heard somebody use the analogy of the caterpillar becoming a butterfly. The caterpillars spin cocoons around themselves, and inside there they start to work on themselves, and the reason they do that is because they flash on the fact that they could be more than little creatures crawling around in the dirt. They could be more. And my friend John can be more.

We all can be more. If we were pulled into our quiet place like that caterpillar into that cocoon, we could start to grow wings. But we’ve got to learn each stage of that lesson, because if we broke open that cocoon and said, “We’re gonna let that creature out of there,” before it was ready, then we’d destroy it. That doesn’t mean that we can’t have some help along the way. That’s what Highlander’s about, and the King Center and some other places. It would be wonderful if the school system were about that: helping people understand that you can be more; that when you’re ready, and your wings are strong, you can fly out and soar to great heights. □

* A United Church of Christ center in McIntosh County, Georgia, 30 miles south of Savannah, used frequently for the Citizenship Training Project workshops.

Tags

Eliot Wigginton

Eliot Wigginton teaches high school in Rabun Gap, Georgia, and edits the Foxfire series for Doubleday/Anchor Books, which are taken from the student magazine by the same name. A longer version of this essay appears in Foxfire 6 and is used here by permission of the author. (1982)

Sue Thrasher

Sue Thrasher is coordinator for residential education at Highlander Center in New Market, Tennessee. She is a co-founder and member of the board of directors of the Institute for Southern Studies. (1984)

Sue Thrasher works for the Highlander Research and Education Center. She is a former staff member of Southern Exposure. (1981)