This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 6, "Waging Peace." Find more from that issue here.

"Someday the demand for peace among the people will be so great that the governments of the world will have to step out of the way and let them have it" —Dwight D. Eisenhower

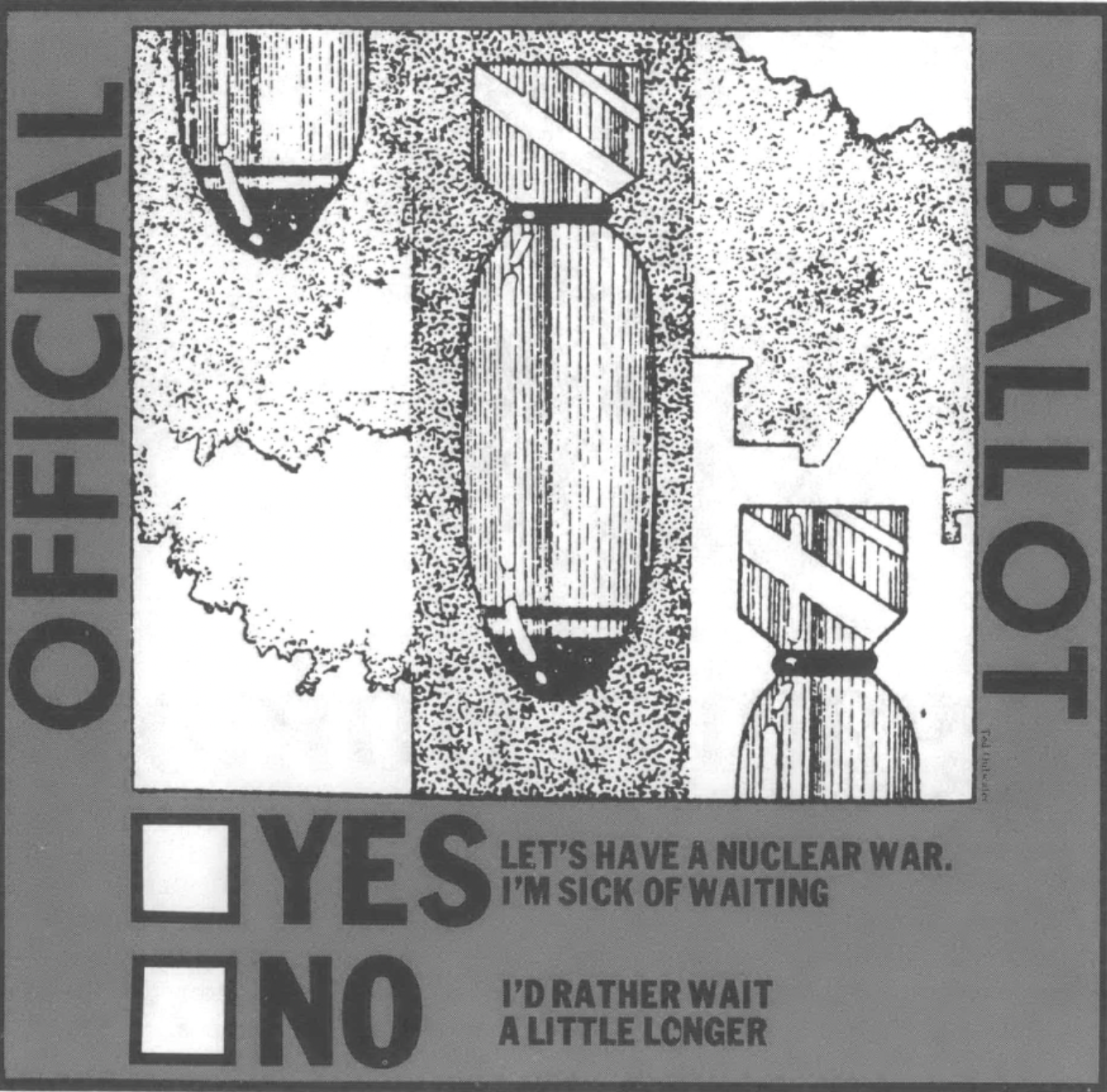

In November of 1982, the voters of the city of Atlanta will have a chance to vote for something that really makes a difference: a proposal to halt the nuclear arms race and transfer spending from the military to support productive jobs and fund human services.

The key to successful organizing is to select issues which are relevant to people and their circumstances, and on which people want to work. Historically, disarmament organizers appeal predominantly to well-educated white middle-class Americans. The Atlanta Nuclear Freeze/Jobs with Peace Campaign will enable organizers to break out of this traditional limitation of the peace movement. The campaign, a coalition effort with participation from labor unions, political parties, peace groups, Third World communities and religious groups, uses elections as the key organizing approach and stresses economic issues in its platform.

Ballot initiatives involve more people in organizing than any other approach. Atlanta has nearly 200,000 registered voters; even if the voter turnout for the election is only 30 percent, 60,000 people will be thinking, deciding and casting their opinion in a concerted fashion. The impact of such a vote on future organizing and on influencing public officials is significant. In addition to affecting voters, the mass-scale advertising, organizing and media coverage reach large numbers of people who won't vote on election day. The election catalyzes many people to cast a vote in their minds. Thus, building support to win an election serves a broader public education purpose.

The Atlanta Nuclear Freeze/Jobs with Peace Campaign parallels similar programs elsewhere. Currently, activists in eight statewide and two dozen city- and countywide campaigns are working toward the 1982 elections in which 25 percent of the U.S. population will cast votes on the nuclear freeze proposal. In addition, Jobs with Peace proposals, dubbed by the New York Times as a plebiscite on Reaganomics, will be voted on in over 50 U.S. cities and towns. The Atlanta campaign combines the attractive elements of each in a unified proposal, and is the only such vote taking place in the heart of the South.

The impact of the freeze movement against the nuclear arms race is having an effect on national policy makers. Successful work in communities is being translated into national public opinion polls and national organizations, which use the combined impact of local work to move national politicians. Many people interpret the initiation of START disarmament talks between the U.S. and U.S.S.R. and recent votes in Congress as an outgrowth of citizen pressure to reverse the arms race.

There is no question that low-income, Third World and blue-collar constituencies are just as concerned about the threat of nuclear war as any other segment of society. However, these constituencies have been less visible in the anti-nuclear weapon movement. To counter this trend, the Atlanta campaign adopted the approach of the national Jobs with Peace campaign, which keeps the issue of jobs and the economy front and center and linked to disarmament issues. This approach gets a strongly positive response from a broad cross-section of the populace. For example, the 1981 Jobs with Peace initiative in Boston won in every single district, from conservative, white working-class South Boston to predominantly black Roxbury. In all, 72 percent of the voters in Boston voted for Jobs with Peace.

The Atlanta Nuclear Freeze/Jobs with Peace Campaign grew out of a visit by Frank Clemente, an organizer of the successful Boston Jobs with Peace drive. At a workshop sponsored by the Southern Project on Women's Economic Rights, Clemente outlined the strategy used in Boston. "We realized that support from the inner city was necessary to win. The way we got inner-city support was by dealing with issues that relate to inner-city people."

Moving into electoral politics requires a big change of approach for peace activists. An electoral campaign calls for advertising and organizing on a mass scale. All efforts are targeted towards turning out sympathetic registered voters in order to win.

The first step to getting a vote on an issue is to get it on the ballot. In Atlanta, this step has constituted the toughest part of our work thus far. It took us half a year, but the issue is now on the ballot for November 30, 1982. In the course of getting onto the ballot, we learned six rules for electoral campaigns such as ours.

Our work began by researching electoral laws in Georgia and Atlanta to determine if it would be possible to place the referendum issue on the ballot. Local political experts said it would be impossible to hold a referendum on the issue. Frances Duncan, Chief of Elections in the Georgia Secretary of State's office, flatly said it would be illegal. This taught us Rule 1: don't blindly accept the opinions and interpretations of others.

We discovered that the Atlanta city charter does provide for initiatives and referenda. Issues can be placed on the ballot by petition of registered voters or by vote of the city council.

Since the referendum process has not been widely used in Atlanta, local officials have little experience in or knowledge of the procedures or rules involved. The legal issues were not clearcut, and we found differing opinions about the legality of our approach, which brings up Rule 2 of working on ballot issues: politics is stronger than law. Or, as stated by Atlanta city council member Debby McCarty, "If city council wants to do something, we can find a legal way to do it."

This rule made our strategy very clear: get the city council to vote to place the Nuclear Freeze/Jobs with Peace proposal on the ballot.

This strategy emerged during the spring, with a working group of about 10 people meeting biweekly to coordinate research and lobbying activities. The first phase of organizing culminated on April 20, when six council members — Bill Campbell, Mary Davis, Myrtle Davis, John Lewis, Debby McCarty and Elaine Balentine — introduced the Nuclear Freeze/Jobs with Peace proposal to the 18-member city council.

Prior to introducing the proposal we had done a complete analysis of the city council to determine the process the proposal would take, which committees would be involved and who would be our potential opponents and allies. We researched past votes, read about the structure and rules of the council and met with sympathetic council members. According to Rule 3, it is crucial to plan the approach to the city council in advance, to know what will happen before it takes place. Certainly, there will be plenty of surprises, but since almost everything a city council does is decided in advance, much can be anticipated and managed.

We knew in advance that our proposal would go to a committee in which we had a majority of supporters, but also in which the chairperson initially opposed our position. The first surprise we encountered was when Barbara Asher introduced an alternative proposal to have the city council endorse the Nuclear Freeze/Jobs with Peace concept rather than place it on the ballot. Since this move would eliminate the educational and publicity value of an election, it was not something we wanted.

The fault was ours for not being better prepared and for not doing better lobbying ahead of time. The main argument raised at the meeting was that the city council should not waste time on a question that is not local. In our defense, council member Mary Davis noted that military spending and the nuclear arms race are of local concern everywhere, since it is taxpayers' money that pays for the arms race and city residents' lives which will be lost if a nuclear war is fought.

Asher's proposal passed anyway on May 17, and in June the original cosponsors introduced a slightly revised referendum proposal, with a better lobbying plan to back it up. Campaign activists coordinated phone calls and letters from key neighborhoods, those whose council members were sitting on the fence.

We encountered tough legal obstacles at this stage as well. The Secretary of State's office claimed it had final say on placing the issue on the November ballot, and told the city council it would oppose the referendum. Marion Smith, associate city attorney, drafted a legal memo supportive of placing a referendum on the ballot; that memo was later overruled by another memo from assistant city attorney Gary Walker. At the next council meeting, the opposition was able to use the legal confusion to out-politic us and cause the proposal to be tabled.

Bill Campbell, one of our cosponsors, pointed out to us that we failed to provide key spokespersons on the council with facts to back up their position. No council member can stand and speak without hard answers to the questions that will be raised. Thus we learned Rule 4: know every angle that can be raised against you and develop solid answers and evidence to back up your position. Fortunately, by quickly redrafting the proposal, we were able to have it reintroduced that same day.

At every step activists had to attend each council and committee meeting, to write and type each proposal before the city council, to meet with all the supportive council members and brief them on the status of the proposal and to prepare all the research and background material. Activists cannot expect council members to do all this work: they have numerous other issues before them and almost always give priority to more pressing city business. Thus comes Rule 5: take the initiative to communicate with council members and be persistent in doing so.

Our last opportunity to have the city council vote on the referendum proposal in time for the 1982 election was in August. The final obstacle was the number of votes we had in the full council. Gary Washington, a campaign activist and veteran of several local labor strikes, set the pace for our community outreach by contacting black ministers, neighborhood leaders and union members to get them to contact undecided or wavering council members.

The day of the council meeting, we were still touch-and-go with the votes. The last doubt was removed when James Howard, who would have voted against us, voluntarily left the meeting to avoid voting, and Barbara Asher changed from voting against to voting for us.

Council members take a political risk when they actively support controversial issues. Activists need to understand this point and follow Rule 6: give credit where credit is due and arrange for positive media coverage for political supporters.

It was difficult to develop our campaign apparatus while working on ballot access. During late August and early September, we took the first steps in this direction, and the structure of our work for the coming two months is being set in place. Tim Johnson, who had managed Billy Lovett's gubernatorial campaign, has taken on the job of campaign manager, and we have established an office in the American Friends Service Committee building. Numerous volunteers commit one or two days each week to work in the office.

The next steps of the Atlanta campaign will be to reach the media and to determine which of the city's 180 precincts should be targeted for canvassing, outreach and placement of yard signs and posters.

We have ranked Atlanta precincts according to seven characteristics to determine the top 100 precincts which tend towards a favorable vote. "In this way the door-to-door canvassing and telephone banking will be targeted to areas in which we can expect support, rather than wasting our time in areas which won't support us," according to Margaret Roach, canvassing manager for the campaign.

We are also holding events designed to attract media coverage. When Jonathan King, a biologist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and an activist in the national Jobs with Peace campaign, stopped in Atlanta, we arranged a fundraising reception and a series of news conferences. Another press conference, highlighted by a statement from council member John Lewis, grew out of a survey of voters in an earlier election. That survey found that four out of five voters wanted to see the Nuclear Freeze/Jobs with Peace issue on the ballot.

Volunteers who had worked for Georgia progressive candidates in the past are now providing invaluable help in this campaign, continuing to raise progressive issues and build a solid campaign that will benefit the entire progressive movement in Atlanta. We all envision work on the Nuclear Freeze/Jobs with Peace campaign as helping build strength for future cooperation on other community issues in the city.

Sheer determination and hard work have brought us success thus far. We have laid a solid base for our campaign and fully expect to win in November.

Tags

William Reynolds

William Reynolds is disarmament coordinator for the AFSC-Southeast office in Atlanta. (1982)

William Reynolds is the director of the American Friends Service Committee’s Nuclear Cargo Transportation Project. (1979)