Broken Promises, Shattered Dreams

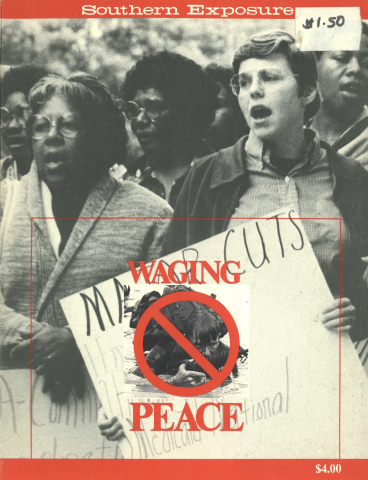

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 6, "Waging Peace." Find more from that issue here.

During the Civil War, thousands of slaves fled from their plantation owners to join forces with the Union soldiers. Initially, the slaves were held in protective custody, but by 1861 field units were authorized to employ the fugitives as workers, although they were not to be armed as soldiers. They planted crops, tended mules and horses, cooked, laundered, repaired bridges and dutifully carried out their role as support workers for the Union forces.

By May, 1862, David Hunter issued a call for Negro soldiers and in a few months had enough recruits to form the South Carolina Voluntary Regiment. However, since there was no authority to support Hunter's actions, the regiment had to be disbanded. The black soldiers were sent home without ever having been paid for their service to the army. Thus began the legacy of discrimination and unfulfilled promises that plagues the United States armed forces to this day.

When Robert was 20 years old in 1941, there was little more opportunity for poor blacks in Shelby, Mississippi, than there had been during the Civil War. The small, segregated town did not even have a high school for black children. Those who could afford it sent their children to an all-black boarding school in Mound Bayou. But Robert's family had no money for tuition, so, like thousands of under-educated blacks, he took the only jobs available: he picked and chopped cotton, cut wood and pulled stumps to earn a living.

A big, strong youth, Robert lived with his mother and sisters. They eked out a meager existence, often depending on credit from a local store. It was a hard life, and like young people everywhere, Robert had dreams. He longed for nice clothes, a car, and to see what the world was like outside of his Mississippi Delta homeland.

The U.S. Army seemed to be the answer to the dreams that sustained Robert: money, travel, education, benefits, security for his old age through pensions, and medical treatments for life at Veterans Administration hospitals anywhere in the United States. Robert signed up.

Anita was born 22 years ago on a small plantation near the same town where Robert grew up. She was introduced to hard work early, and by the time she had finished the eighth grade, she had chopped and picked cotton in some of the same fields that Robert had worked a generation earlier.

After leaving the plantation, she and her family moved to Shelby, where she attended public high school — still segregated, although no longer by law. She graduated from a small private college near Jackson in May, 1982.

Armed with her degree in biology and her resume showing the part-time jobs she'd held, beginning in high school, she set out to find work. She applied to the state's medical school, hospitals, laboratories, private companies, state and federal agencies, and finally to department stores. She has not found a job; and, since everyone talks about experience in the tight job market, she's convinced that she's not going to find work — unless she goes back to the fast-food chain that hired her when she was still in high school.

Anita was accepted to the Radiology Technology Program at the University Medical School in Jackson, but as an alternate. If someone defers entrance, she will be one of the people considered for the position. She's aware that the economic crunch has forced a record number of applicants to seek admission to professional and graduate schools. She's certain that being black and female and not making a perfect score on the Graduate Record Examination will prevent her from being selected for the program. Like Robert, she found her way to the local recruiting office.

The army recruiting officers promised to provide her with the same training that she's seeking at the medical school, to pay her a nice salary and to pay for additional education when she completes her tour of service in three years. And as they promised Robert in 1941, the army offers her the opportunity to travel, to meet new people and to do something worthwhile. She perceives this as her only chance to get the training that she wants.

Five years ago Zebediah dropped out of high school, where he was failing his sophomore classes, to join the army. Zeb says, "I wanted to learn a trade because I had figured out that I wouldn't make it too hot trying to finish school and getting a good job." He was more interested in the training the army offered than the travel. Zeb got training in electronics. He was sure that he'd find work with the telephone company, but two years after discharge he has been unable to find steady employment. None of the part-time, short-term jobs he's found had anything to do with electronics. He has not received any help from the Veterans Administration Center in job placement. He is thinking about re-enlisting because he cannot find a job.

The common denominators in these three case histories are:

• race — all three subjects are black (although poor people of all races experience similar difficulties);

• poverty — all are from low-income families; and

• upward mobility — each seeks to improve his or her station in life. At least one other factor is com mon to the three: faith that the army would fulfill its part of the bargain agreed upon when they joined up.

"I would no more teach children military training than teach them arson, robbery, or assassination" — Eugene V. Debs

Robert enlisted under the Selective Service Act of 1940. In 1944, he was one of 701,678 army personnel and one of nearly a half-million GIs in overseas units. After three-and-one-half years of service, he had attained the rank of sergeant in the military police. But then he became ill and was hospitalized overseas. The diagnosis was asthma. All of his subsequent medical records document the asthma and the treatment. He was declared "unfit for long marches, vigorous physical exertion, working under field conditions. Should be stationed in fixed installation, in zone of interior." So reads an official document from Thayer Hospital in Nashville, Tennessee.

Discharged from the army, Robert returned to his home town and after a brief period rejoined the work force. His asthma kept him from pursuing certain types of work, such as working in the cotton fields or mills where excessive dust kept him from breathing. He worked as a carpenter and at other odd jobs to support his family. Medical records from local doctors, clinics and hospitals show that he has been treated periodically for asthma. Two years ago, when Robert was 62, he filed for medical disability. After a year of examinations and trips to Memphis, to Jackson and to local VA offices, the VA told Robert that he was indeed disabled — 10 percent worth, which equaled $48 per month effective January 28, 1980. Robert feels that he should be given a 50 percent disability, since he is unable to work now because the asthma is so bad.

Robert feels that he has been cheated by the army. He worked, after being discharged, to take care of his family and never attempted to burden the army with his medical problems. At age 64, he expected the army to follow through on the promises it made to him 38 years ago. According to a counselor at the Vets Center, an advisory group primarily for Vietnam veterans, Robert is not likely to win his appeal.

When Robert's plight was recounted to Anita, she was not perturbed. She believes that there will be some exceptions to the army recruitment promise to "teach you a skill that will last a lifetime," but she has also talked to men and women whose professional skills were acquired through their military training and service. And looking squarely at the questioner, she asks the hard question: "Do you have a better suggestion for a way out of unemployment?"

Of course, on the issue of unemployment, America doesn't have a better answer. The latest figures from the Department of Labor show unemployment near 10 percent, the highest rate of joblessness since the Great Depression, with unemployment among black workers at 18.7 percent and expected to go higher. At 49.8 percent unemployment, young blacks are far and away the most severely affected among the jobless in this country.

While the military may offer a quick exit from unemployment lines for young people today, many vets, especially those who served in Vietnam, have found that their service hitch provided them with no long-term solution.

Anita and Zeb are too young to really appreciate the problems of Vietnam-era veterans. Caught up in junior high school activities, they were removed from the bitter disappointments of veterans returning from active battle in Vietnamese jungles to their home towns. They couldn't know how much these soldiers were rejected because of their participation in Vietnam. They didn't know that most of these vets could not find work, even though there were jobs available, because employers didn't trust them. They didn't know that by 1974 an estimated 125,000 Vietnam vets were serving time in American prisons for crimes committed since their discharge from service.

Max Cleland, a decorated and legless Vietnam veteran who was appointed to head the Veterans Administration in 1977, told U.S. News and World Report in 1978 that there were problems: "To the best of our calculation, around one out of five Vietnam-era veterans has some kind of problem that he hasn't been able to deal with, that has kept him from entering the main stream of society. It can be lack of education, unemployment, drugs or alcohol, or a personal problem.

"The bad part of the readjustment was complicated by the negative image of Vietnam veterans. I've heard of enough cases . . . where the employer says: 'Hey, look, I don't want to hire a killer.'"

And the military did little to try to correct the problems. Veterans interviewed by various groups say that, although they came straight from battlefields, they received no debriefing, counseling or even adequate evaluation before going home. In the March, 1979, issue of Corrections Magazine, veterans in prison said they received no help either. Many of them showed bizarre behavior after returning from Vietnam and they wonder why no one, especially the VA, recognized their unique combat-related symptoms and offered assistance. Even after the Vietnam vets' incarceration rates rose to an astonishing high, the VA was of little help. And now there is talk of denying military benefits to any vet who is imprisoned.

The parents of low-income youth, especially, support the military as a way to save a child from the streets, the prison or worse. They see Uncle Sam taking over their sometimes wayward and unmanageable son or daughter and instilling some discipline and responsibility.

"The army will make a man out of him," a widowed mother in Mound Bayou said to herself three years ago when she drove her only son to the recruiting office. Her son would not go to college, nor would he work at the menial jobs available to him. The son, now employed as a police officer, married and "settled," is proof positive, as far as the mother is concerned, that she was right in giving him to Uncle Sam for three years. She is convinced that his stint with the army helped him achieve a sense of responsibility and discipline. Yet she has no answer for other vets in town who went through the same military experience and are now drug addicts, or who are serving time in the state prison for various crimes.

Granted, there are many veterans who've secured skills that have enabled them to get well-paying jobs when they completed their service hitch. And VA benefits have given many vets the opportunity to go to college or to buy a home. But far too many others are cheated out of the training they were promised and the benefits they deserve — especially blacks and other people of color.

According to a Congressional Black Caucus report, "The total effect of a black serviceman's encounter is that when he leaves he is usually in worse condition than when he entered. He has generally received little training . . . has been subject to harassment and discrimination at the hands of his superiors and he too often winds up with a less than honorable discharge which guarantees that his civilian life will be at least as difficult as his former life." In 1979, although blacks were only 32 percent of army personnel, they comprised nearly 51 percent of the army prison population, and they received nearly 40 percent of all less-than-honorable discharges.

Congress is now being asked to appropriate more money to retain the senior, more experienced, better trained military personnel — who also happen to be overwhelmingly white. On the other hand, business experts agree that it is becoming less economical to hire and train unskilled young men and women for highly technical jobs in the private sector; few entry-level jobs exist, and the commitment to create those jobs is not forthcoming. The combined effect of these practices is to ensure a military recruitment pool of young people desperate for jobs and security and willing to work at the lowest possible cost, while offering greater financial rewards to keep high-level, predominantly white personnel from leaving the military for jobs in the private sector.

As the generals polish their brass and count their bonuses, thousands of poor and unemployed young people like Zebediah will continue pouring into the nation's recruiting offices, writing their own dreams into the fine print in their "contracts." And like Zeb, when they get out and can't find a job, they'll admit that the army never really promised them anything. They may conclude, as Zeb has, that the inability to find work is their own fault and that the only way to "be all that you can be" is to re-up and learn another skill in the service. Maybe. If they can trust Uncle Sam to fulfill his end of the bargain.

Still, there is no easy answer to Anita's poignant question: "Do you have a better way out of unemployment?" We can only point out that the student loan money which would have enabled her to pursue her medical career in the school of her choice has been diverted to the military; that medical benefits for people like Robert are being used to beef up our nuclear arsenal; that job placement programs which could have helped Zeb find work in the civilian labor force have been gutted while slick new recruitment ads and brochures promise, "The army can make you feel good about yourself."

No matter what your race or sex or age is, it's hard to feel good about yourself if you can't support yourself. For the young and healthy, the armed forces seem to offer the only way out. For the not-so-young and not-so-healthy, and for the soaring number of unskilled and uneducated young volunteers who are rejected for military service, what is their way out of unemployment? Will sub-minimum wage jobs loom as a beacon of hope to them in the same way military service lures their brothers and sisters? How many will turn to crime? Or suicide?

The overall effect of the diversion of money and personnel from civilian support programs to the military is to stratify our society into a highly trained, highly educated elite; a carefully selected, sophisticated military; and an underclass which is denied access to skills and education in order to provide an eager pool of workers who, like the fugitive slaves in 1861, perform dead-end menial chores for the elite.

So when the army promises Anita and Zeb that it will teach them "a skill that will last a lifetime," they may just find themselves entwined in the military version of Reagan's so-called "safety net" — the one that holds the underclass in its place, out of sight and mind of the elite. And out of hope.

"The pioneers of a warless world are the young people who refuse military service." —Albert Einstein

Tags

L.C. Dorsey

L.C. Dorsey is director of programs for the Delta Ministry and associate director of the Southern Coalition on Jails and Prisons. She is the author of Freedom Came to Mississippi, published in 1978 by the Field Foundation. (1982)