A Fine Old Tradition

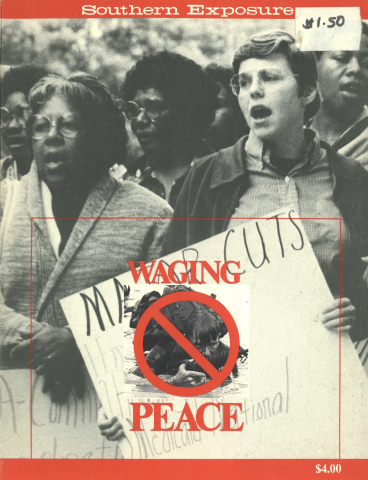

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 6, "Waging Peace." Find more from that issue here.

The author of our Declaration of Independence, the Virginia native Thomas Jefferson, once opined, "Military conscription represents the worst intrusion of a national government into the private lives of its citizens and strikes at the heart of every precept on which our Republic is founded."

Draft dodging and draft resistance have a venerable history in the South, as elsewhere in the nation. The first real stronghold of resistance to military conscription during the Civil War was the Appalachian mountains. Whether in the hill country of Vermont or of North Carolina, the attitudes were much the same. When the draft laws were passed, untold numbers of young men fled to the hills, and beyond, with sympathetic help from mountain natives.

As the Southern forces of secession and government-approved enslavement became more hard-pressed, they beat the bushes for every able-bodied man into whose hand they could thrust a gun, only to be met with, "The Bible says 'Thou shalt not kill,' and I won't." So widespread were such attitudes that the Civil War governor of North Carolina, Zebulon Baird Vance, himself a mountaineer native of the Asheville area, was moved to remark, "The hills of Carolina pose a greater threat to the continuation of the Confederacy than all the armies of the North combined."

The pervasiveness and persistence of such attitudes can be seen in the widespread refusal of young men to register for the draft today. And they are well illustrated by these Vietnam-era vignettes.

BILLY

Billy and I go back a long way together — all the way to junior high school. He was always a lover of nature, spending as much time as possible hiking, exploring woods and fields, camping out. He was never inclined to do much thinking about things like war and drafts and Vietnam and conscientious objection. He mostly just wanted to be left alone to live his life his way.

At age 16, Billy learned of an opportunity to earn a lot of money in a short time, working in a cannery on the West coast. Nature lover that he was, Billy just camped out all the way out West, then came back by a different route, camping out again as he came.

At age 18, Billy had no choice but to do some thinking about the draft and Vietnam. He had entered college, just as his family had expected of him. That choice gave him a student deferment, at first, but there was always the question: what about the draft when you're not in school. Going along with the government's expectations of him was a definite choice — and that choice was not the one that Billy wanted. On the other hand, he found nothing in school that appealed to him. He felt trapped, frustrated. After one year, he dropped out of school.

Selective service immediately pounced, ordering him for a physical. But Billy's summer work lay a-waiting out West. So out West he went, dutifully notifying his local draft board of that fact, and of the reason for it. . . .

. . . Or, at least, of one of the reasons for it. Besides the opportunity for a job, Billy knew that his draft board would have to transfer all of his records to Walla Walla, Washington. Just about the time his records made it to Walla Walla, he would get this itch to climb Mount Rainier, or to get lost in the wilderness of Yellowstone or Yosemite for a couple of weeks. Then it was home-sweet-home to Raleigh, North Carolina, to work in surveying; and then, whenever the draft people were about to close in, to put in another semester at State University.

This rambling lifestyle went on for about five years.

In those five years, Billy had done a lot of thinking about the draft, of course. He knew that no one could have a one-inch-thick draft file like he did without the selective service people having pulled at least one major boner: the sort that would get any case thrown out of any court, if it came to that.

Now, in the course of all his wanderings, Billy had taken up photography. Some of his nature pictures were — and are — simply breathtaking.

One afternoon, he went down to the draft board office in his home town and asked to see his file. He didn't make it obvious at first that his object was to take a picture of everything in it.

He was wise not to make it obvious. The draft people (like government people everywhere?) were intensely jealous of their paperwork. It never seemed to occur to them that any file which they had on hand was, after all, a repository of information with potentially life-shaping, if not life-shattering, importance to the individual whose name appeared on that file. Not that you couldn't get a copy of your file upon request — you could, for a price. I believe Billy told me it was a dollar a page, plus the cost on a per-hour basis of the labor involved in having it transported under the strictest of security measures down a long hallway to the copier.

Into this nest of security consciousness and cost effectiveness strode Billy, 35-millimeter camera with black-and- white film safely tucked away in a nondescript valise. He made some unusual requests: "Could you let me see my file over at that table, by the window? Wonder if you'd mind raising the blinds a little higher — that's better."

Out came the camera and click, he had his first picture — the outer cover of his file. The poor clerk was so startled that, at first, she couldn't even respond . . . just stood there staring in disbelief. Billy opened the file and click, took his next picture. The clerk started yelling at him. "But you can't do that!" Click, and he flipped the page over; click, flip, click. "But this is strictly against the regulations! You just can't do that!"

As a matter of fact, they could do nothing to stop Billy, as a hasty check with the state headquarters of Selective Service bore out. He had a right to see his file, and nothing really forbade his photographing it at his own expense. Billy just ignored the commotion, flipped and clicked.

Finally, his exasperated draft board secretary typed a memo. It read, simply, that on that date, one William Butler Bryan had come into local board whatever-number-it-was and taken a picture of everything in his selective service file. She shoved the memo under Billy's nose. He read it, click, took a picture of it, raised his camera and click, took a picture of the secretary. When Billy, smiling and oh-so-polite, thanked her for her help in positioning the file so as to get the best possible light, she said things the recollection of which turns Billy fiery red with embarrassment.

That was three years before the lottery system was put into place, as part of the overhaul of the old draft law. Billy remained vulnerable to the draft all three years. Maybe it was just a coincidence, but he never heard from them again. When the lottery was drawn, he had something like number 300 — something so high that there was no way he'd ever be in the top priority selection pool. A year later, he turned 26; and under the new law, anyone over 26 was too old to be drafted. His precious file, which had criss-crossed the country with him so many times, was simply burned in a selective service incinerator.

JIMMY J.

There is a myth in our land that anyone who is accused of a crime is presumed innocent until proven guilty. Anyone who has ever been arrested for a major crime knows from painful experience how much a myth — how much a lie — that really is. My experience with Jimmy J. is the best example of that which I know.

I have changed my friend's name, for his sake and his family's. He is from an "old money" Southern family. His daddy was, perhaps still is, a banker. The little church that they all attended bears the family name, as does each of the individual pews and the stained-glass windows (each one having been given by different surviving family members "in loving remembrance").

Jimmy J. grew to maturity at a time when many of his peers were questioning authority. Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X, those most authoritative questioners, had set the example, as had protesters of earlier wars. Midway into the Vietnam era, Jimmy J. found much in those examples which spoke to his condition. When he became 18 years of age, he took the (to his family) radical, unheard-of step of registering for the draft as a conscientious objector. Jimmy J. had a good case for such recognition, but his draft board had never granted such recognition to anyone; and, family standing or no, they weren't about to start doing so with him. Upon being turned down, he lacked the counseling essential to successful appeals to the state or national draft boards. His family had a hard time understanding him and could not or would not come to his aid.

Cut off from all he had ever known and loved, and now impoverished, Jimmy J. turned to some new-found friends who tried to help. But there was little that they could do, except be there. When Jimmy J.'s case came up in court — yes, he had been ordered to report for induction, and had refused — his court-appointed lawyer botched what ought to have been a simple case.

Jimmy asked only for the right to serve his country in a way compatible with his faith, which meant service in some non-military, non-combatant way, but such things as truth and justice, or even legality, didn't matter much to that court. And so he went to prison for 18 months, despite the fact that his draft board had been the first to violate the law by denying him recognition as a conscientious objector.

In February of 1973, I was arrested myself for a very different kind of violation of the draft law. That same week, a good friend named Chuck, the son of a career marine, was tried and convicted of the exact same offense for which I was arrested. My own arrest was, in fact, connected with the government's burning desire to get Chuck. In the early 1970s, he helped to establish a small organization called N.C. Resistance, the goals of which were to promote both draft and war tax resistance throughout North Carolina. He helped to organize several demonstrations at which, among other activities, draft cards were collected to be mailed in to the President of the United States. By February, 1973, he had become enough of a thorn in the government's side that the U.S. Attorney's office badly wanted him put away. They thought that arresting me would help their case against Chuck.

Chuck appealed his conviction, and my case was put on hold until his was resolved. Two months later, Jimmy J. was released from the Petersburg Federal Reformatory in Virginia. I knew that, if convicted, I would be likely to serve my time in the same prison. I learned from a mutual friend where Jimmy J. was living, and for two weeks I tried calling him. Someone else always answered, always took a message, always promised to have him call back. He never did.

Weeks went by, and then I saw Jimmy J. I was on my way into the little Quaker meeting that I attended in those days, when he came out the front door. I greeted him heartily, and he returned my greeting just as heartily. He then grew most solemn, and said that he had something to say to me.

He knew, of course, that I had been trying to reach him, but he had been unable to allow that. He had been released from prison after serving 18 months of a three-year sentence. As a condition of his parole, Jimmy J. had to do certain things, and avoid doing others. He had to do them for the remaining 18 months of his original sentence. If he violated any of those conditions, even if he had only one day remaining of his original three-year sentence, he could be returned to prison to complete the full term; in his case, another 18 months!

One of the conditions of his parole was that he was never to have any contact with two specific individuals — Chuck and me.

I couldn't believe what Jimmy J. was telling me. I gulped, "You mean, we were specifically mentioned, by name?" Nodding, he replied, "By name." My disbelief deepened as Jimmy J. continued his story.

Knowing how persistent I can be, he had had a talk with his parole officer about the problem, and had been granted special permission to have one conversation with me, in person, to explain his distancing himself from me. "And, Jeral, this is that one conversation. Anything you wanted to say to me, or ask of me, do it now."

Presumed innocent? Until proven guilty? Chuck's case was on appeal; and I hadn't even been to court for a pre-trial hearing! I was so thrown off balance by what I had just heard that I became tongue-tied. That situation was not improved by Jimmy J.'s being obviously intent on leaving as soon as possible. Sensing my bewilderment, he thoughtfully volunteered what advice he could about getting along in prison. With that, having explained himself and briefly added what he felt he could, he proceeded down the steps, out of the little meeting and out of my life for the duration of his parole, 16 months away.

Personal liberty, despite a regulatory agency's flagrant violation of its own regulations; freedom of association; a friendship here and there; freedom to worship at the place of f one's choice — these, then, became casualties of Jimmy J.'s act of conscience, his obedience to a higher law and the law's violation of itself. But that's not all the cost. Jimmy J.'s marriage perished while he was in prison. Maybe it would have anyway; but, as many a soldier in far away climes has found, distance and time can sometimes destroy even a good marriage.

It never mattered to the parole officer that Chuck's conviction would be overturned as early as the following October; or that I would never even go to trial, much less be proven guilty of a federal felony. We stood accused, and that was enough. Jimmy J. had to prove his sincere repentance by avoiding even the appearance of any further "wrongdoing."

EPILOGUE

Quite by accident, I saw Jimmy J. one more time. I was working in a library when he came in looking for a book. He stared at me in horror,

as if I were some bizarre alien creature or a known carrier of the plague. Before I could even say good morning, he flew from the room, without, as far as I know, procuring his book. I later learned that he had moved to another town, found another job and place to live. I never saw him or heard from him again.

As for Chuck, his case was overturned on something more substantial than a mere technicality. He had been convicted of failing to possess his draft card, having mailed his to his local board some months prior to his trial. The appeals court decided that that act alone did not constitute a violation of the law — a decision that would still stand in the seven states covered by the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals, if ever a new draft law is enacted. He remains a deeply committed activist, having since worked for both the American Friends Service Committee and an agency aiding migrant workers in North Carolina, just to name two of his "Movement" jobs.

Billy has become a foreman with a surveying crew, somewhere on the northwest coast. He and his wife have one child. I understand from his family that he is still an avid and superb photographer.

I consider my having been willing to send my draft card to my local draft board, and to suffer the resulting risk of imprisonment, one of the true acts of courage of my life. Having the example of Chuck, and the history and traditions of the Quakers, all before me, was deeply inspiring. And, as the seemingly endless war dragged on, I found out that I had to do "something more" than merely write letters, sign petitions, march in demonstrations, or stand in vigils. After all, I had done all of those things for years. I have had a copy of the warrant for my arrest and of the indictment from a grand jury framed. They now hang on my workroom wall, alongside my high school diploma, college degree, membership in an honor society, certificate of registration to be a registered nurse, and marriage license.

Tags

Jeral Mooneyham

Jeral Mooneyham is a critical care nurse in the coronary care unit of the Durham Veterans Administration Medical Center. He is active in Durham Congregations to Reverse the Arms Race. (1982)