Super Soldier

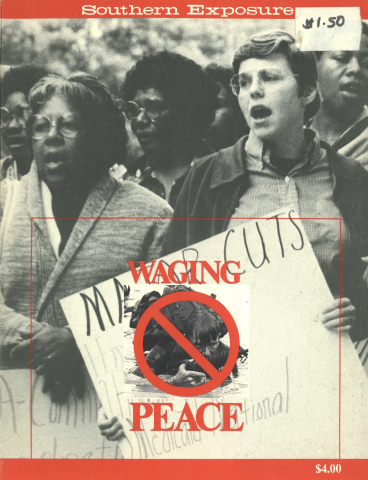

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 6, "Waging Peace." Find more from that issue here.

Imagine the ultimate warrior. A warrior who needs no sleep, no food. A warrior who sees in the dark, kills on command and feels neither heat nor cold. A warrior who does not bleed and feels no pain.

This could describe a Star Wars droid warrior, but if the Department of Defense has its way it may describe the GI of the future: a flesh-and-blood human being stripped of all human needs, all human feeling.

Since 1954 various agencies of the Defense Department have conducted hundreds of experiments designed to create the super soldier.

In that year, a working group headed up by noted psychologist Harry Harlow was established to evaluate army research and development efforts. The group's report recommended the acceptance and integration of psychology, behavioral and social science into the army's research and development activities. It was a beginning. In time it became a pattern.

Just how much of a pattern was made clear in a 1967 address to a group of social scientists given by Donald M. McArthur, deputy director of research and engineering for the Defense Department.

"Twenty-five years ago, perhaps even 15 years ago, a defense R and D [research and development] meeting such as this — devoted to behavioral and social sciences — would have been unlikely. But today it would be unlikely to have any meaningful R and D conference without your participation."

The extent of the participation, from 1954 to today, can only be guessed at. It remains hidden behind clouds of secrecy, tangled in webs of technical jargon and obscured by euphemistic reports. The facts of this article were only obtained by repeated Freedom of Information Act requests over a 10-month period. Much of what the government finally released is minimal or incomplete. What is clear is that the same researchers seeking the ultimate weapon are seeking the ultimate warrior to operate it.

More than two dozen experiments have focused on sleep, with a basic aim in mind, an aim stated in a brief on project ENDURE, conducted by the army's Human Resources Research Office in Alexandria, Virginia. It was, they said, "to establish ways of extending troops' endurance so that the effectiveness of the equipment will not be limited by the user."

For example, a project contracted in 1981 is apparently designed to create soldiers able to operate new extended operation weapons. The newest tanks can operate at a sustained level for days; soldiers, however, need sleep. Doctors W.B. Webb and C.M. Levy of the University of Florida hope to change all that.

Webb and Levy study the effects of sleep deprivation on military performance. They hope to develop what they call "optimum placement of sleep opportunities": how often, when and for how long should tired soldiers doze so they can still perform at peak efficiency. The experiment is one of many aimed at regulating a soldier's need for sleep.

During the Vietnam War certain units, mainly Long Range Reconnaissance Platoons (Lurps) and navy SEAL* teams, often went days without sleep with only dexedrine to "enhance" their performance.

"We called ourselves Uncle Sam's snow-men," James Gilligan, a former Lurp and now a member of Vietnam Veterans Against the War, quipped. "We had the best amphetamines available and they were supplied by the U.S. government."

When I was a SEAL team member in Vietnam, the drugs were routinely consumed. They gave you a sense of bravado as well as keeping you awake. Every sight and sound was heightened. You were wired into it all and at times you felt really invulnerable.

While the Lurps and SEALs were capable of sustained operations, returning to base was often painful.

"They cut you off then," Gilligan said. "So what you had was a lot of guys who had been freaked by intense combat and suddenly they were crashing from a 10- or 14-day speed run."

It was common wisdom in Vietnam for most soldiers to avoid SEAL and Lurp camp areas. They put us into the worst possible combat situations. The screams, the pain, the fear were all heightened by the speed. Then they cut us off and we crashed. We weren't at all rational. If anybody — officer, other soldiers, civilians — got in our way we just walked over them. I stuck a .45 under a commander's nose and threatened to kill him just because he told me to get a haircut. I wasn't even reprimanded. It was just a foregone conclusion we weren't wrapped too tight.

In order to avoid the unpleasant experience of facing dozens of wired, heavily armed, crashing and hostile groups of their own men, the army brass commissioned Dr. M.T. Orne of Pennsylvania Hospital to develop a way to teach soldiers to "therapeutically" nap.

In 1971 Orne began his research. Nine years and half-a-million taxpayer dollars later he concluded, "Unless such control [of sleep] can be taught to individuals not possessing the skill, attempts to teach prophylactic napping would be unsuccessful."

After all that time and money Orne could only conclude that if you can't teach someone to nap it's impossible to teach them to nap when it would do the most good!

Another sleep experiment seems aimed at applying the "chicken-house effect" to the military.

Large-scale egg-producing farms long ago learned they could increase egg-laying by leaving the lights in a chicken house on for 18 or 20 hours. The chickens, seeing the light, would think it was still daytime and go on laying for the entire period.

The army thinks a similar approach might work for them. Under a contract with Human Factors Research, Inc., on the "biomechanical aspects of performance," researcher J.L. McGrath is investigating how "temporal orientation influences human performance." McGrath's research is aimed at "controlling temporal orientation to increase performance."

Although details of the research are classified, one could wonder if future army barracks will be equipped with slow-moving clocks, windows which show only daylight or lights that stay on 20 hours a day. They might even begin to look like chicken coops.

The army also conducts experiments to improve night vision, presumably so soldiers can see better while they stay awake all night.

Early experiments focused on developing night-vision glasses, starlight scopes and the like. These devices were cumbersome, delicate and subject to failure. Current military experiments aim at improving the ability of an individual soldier's own eyes to see at night.

In two experiments on improving night vision, soldiers served as guinea pigs while researchers measured the effect of two dangerous drugs on their night vision. In June, 1978, Optical Sciences Group of San Rafael, California, began administering benactyzine, a powerful central nervous system drug, to soldiers to see if it would improve their night vision. In April, 1980, OSG repeated the experiment using Atropine, a belladonna derivative.

Both drugs dilate the pupil of the eye, which could aid night vision, but both can have serious side effects. Various chemical reference books say the drugs can produce delirium, fever, convulsions, coma and heart stoppage.

A declassified report on one of the two experiments notes that 10 volunteers were used and they reported "mild discomfort."

OSG and its chief researcher, A. Jampolsky, received nearly $700,000 in government funds for the experiments. The military volunteers were not paid for their risk. It was never noted whether the drugs did indeed improve night vision.

Perhaps the most frightening series of experiments are being carried out under the broad banner of "controlling autonomic response."

Autonomic functions are those which are usually automatic but over which we can exercise some control. A good example would be your breathing rate.

One of the most diabolical experiments in this area involves the use of hormones to "change bodily responses to stress and injury." In late 1977, researcher W.F. Hegge terminated an experiment designed to teach soldiers "non-drug management of wound-related pain." In other words — not to feel pain.

Another series of experiments seeks to determine what makes a particular soldier a killer, what will motivate a soldier to fight and what personality traits will influence their performance. Although the military closely guards this aspect of its research, some older reports have been declassified. Their contents are startling and disturbing.

The U.S. Army Personnel Research Office, for example, tried to establish a psychological test for selection of Special Forces officers. Among the items measured were the aggressiveness, energy level and assertiveness of the candidate.

Another ongoing project of the Personnel Research Office seeks to "identify the qualities for effective performance in combat" and to "develop test measures of combat potential."

If the military were attempting to create the "super soldier" for protection of U.S. civilians, these projects might, perhaps, be excused. But in the age of nuclear war, the experiments seem superfluous. The government, however, might have possible applications in mind. One research project, perhaps stirred by the violent upheavals in the nation's cities in the 1960s, was aimed at the role of "minority groups in counter-insurgency," or how to get one Vietnamese ethnic group to fight against another. Although the project was started in 1965, it is still continuing. It is entirely possible that the Miskito Indians of Nicaragua were involved in this program.

Moreover, the projects emphasize "limited warfare situations." Night operations, as well as continuous operations, are more characteristic of guerrilla than conventional warfare. At least one of the army's Human Factors conferences took place at the J.F.K. School for Special Warfare at Fort Bragg in North Carolina — considered by many to be a consulting agency for repressive regimes.

What will be the effect of an army of super soldiers on future wars of liberation? One can only guess, but perhaps, as in the case of the F-15 and the smart bomb, even these technological zombies will be no match for a determined people's struggle. But that is certainly where they will be used.

Vietnam taught our military strategists that technically sophisticated equipment does not necessarily provide the winning advantage. Addressing a Human Factors conference in 1968, General Frank S. Besson, Jr., passed the lesson along: "In a limited warfare situation, man — more than ever — is the weapons system," he said.

* The Navy says that SEAL stands for Sea, Air and Land. When I trained in Vietnam we were told it stood for Small, Efficient, Assault Landing Teams. SEAL missions included "undermining the infrastructure of the enemy" (i.e., assassination). Lurps did intelligence work.

Tags

Elton Manzione

Elton Manzione, a long-time political activist, is the Southern organizer for Vietnam Veterans Against the War. (1982)