This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 6, "Waging Peace." Find more from that issue here.

"It was almost like a dream, going through a dream. I can remember, I always thought that I would never forget the name of the song that was on the stereo at the time, but I have forgotten the name of it. I was getting ready to take my daughter to the doctor and had my hair in curlers. Here I was out to here pregnant and she was sitting in the bathtub. I walked through the living room and saw the staff car sitting out in front of the house. I walked over and I jerked the cord out of the wall to the stereo. Of course I had it on loud because I was back in the bathroom and instead of reaching over and turning it off, I just jerked the cord out and ran back there and grabbed her and put a towel around her.

"They came to the door and asked me, 'Are you Mrs. Breeden?' I said, 'Yes,' and he told me. I said, 'You don't even need to tell me,' I said, 'I know he's dead.'"

Lance Corporal Robert P. Breeden had been fighting in Quang Tri Province, South Vietnam. He was only 22 when he received a fatal gunshot wound on September 18, 1967. Teresa Breeden was then 19 years old and seven months pregnant with their second child.

After 15 years, the consequences of U.S. military involvement in Vietnam still shape her life and the lives of her children. As survivors of a U.S. marine killed in the Vietnam War, the Breedens live not only with the memory and misfortune of his death, but also with the nation's present attitudes towards that conflict and those who took part in it.

Like all citizens, the Breedens have a continuing involvement with the country's military systems and organizations. Their story magnifies the complexities of that relationship, for the confused emotions, loyalties and frustrations are especially acute for members of the '60s generation, like Teresa Breeden — and the children of the war dead.

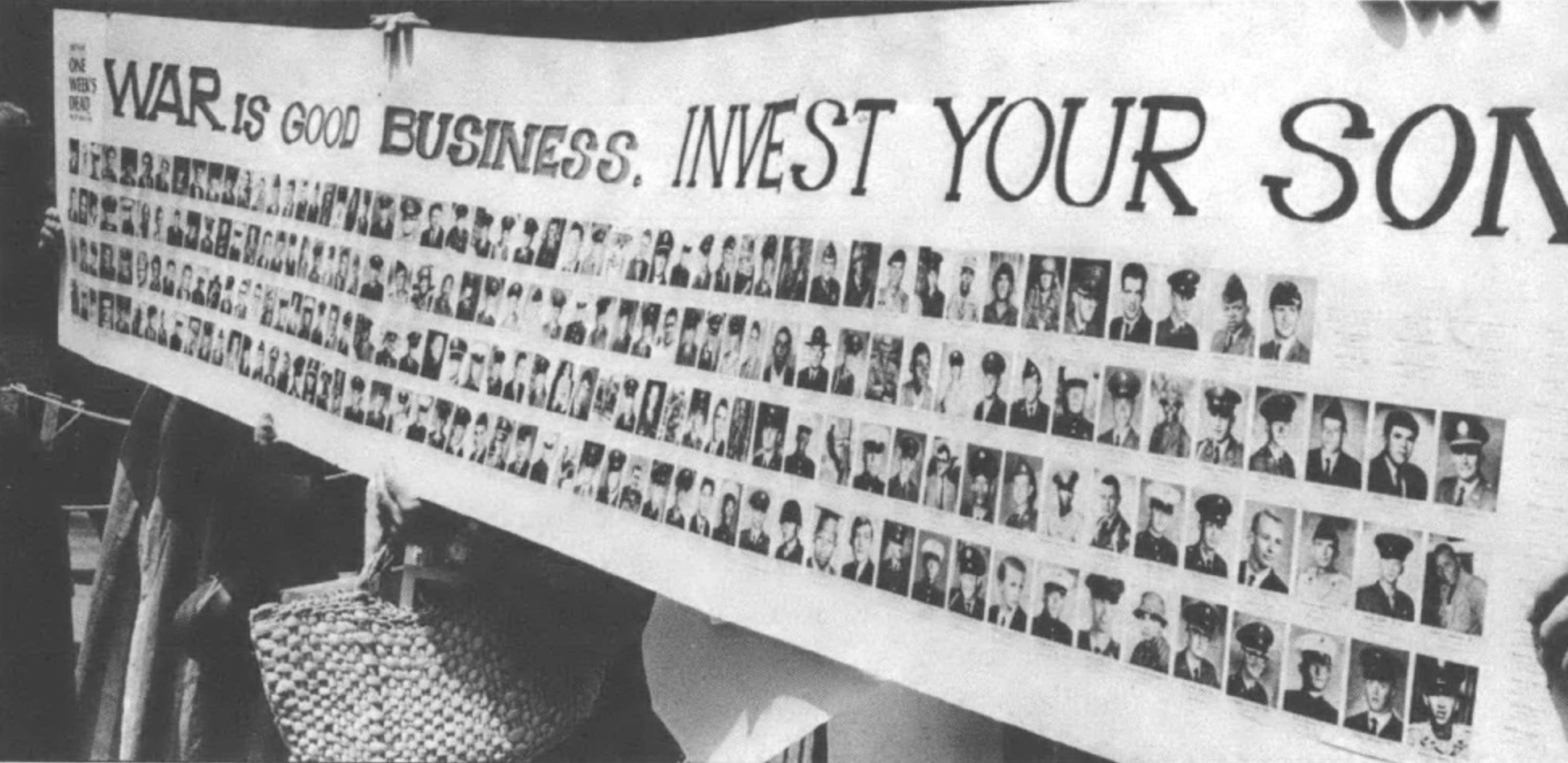

The generation that came to maturity during the 1960s was a divided generation. Images come to mind of a youth-oriented social revolution: the hippie/drug culture, hot summer riots, campus unrest, protest rallies and rock music on the stereo.

Participation of U.S. troops in the Vietnam conflict was a special concern of the young, but not all of them agreed with the war protesters. Bobby Breeden, like many in the South, felt it was unpatriotic to criticize and protest the military's activities.

For a brief time, Breeden had been entitled to a student deferment. Shortly after he dropped out of college, the government informed him that he had two choices: either enlist in military service or be drafted. Although he was married and his wife was pregnant, he enlisted in the marine corps.

Teresa Breeden recalls why he joined the marines and not some other branch of service: "The marines make a few good men. Macho Man image, you know, all that big tough marine stuff. He loved the marine corps. He really did. I'd never talked to anyone that loved basic training; he loved basic training. He was very athletic. He enjoyed hunting so he enjoyed the weapons training that they had. And he enjoyed physical things. When he came home on leave, he had me in the front yard trying to flip me over his back. This was after I'd had the baby, of course. He had played football and track. He loved things like that. So I think the marine corps was just everything that he liked to do."

The first part of his tour of duty in 1966 was spent in Japan. Teresa stayed with her parents to care for her baby daughter. When Bobby came home again on leave in February, 1967, the anti-war movement was receiving more publicity. Emotions on all sides were heated. It was at this time he decided to volunteer for active duty in Vietnam.

"This was during all the draft-card burnings. He was just really uptight about it, and he kept telling me that he was going to go to Vietnam. I can remember sitting in the living room, we were with my parents, sitting in there and seeing the draft-card burnings on TV. He was ready to fight. I kept begging him please not to go there, and he said when he got back to Japan he was going to volunteer to go to Vietnam, which he did." It was also during this time that Teresa Breeden became pregnant with their second child.

After special training for jungle warfare, Bobby was sent to Vietnam in June of 1967. By July, he had already been wounded in combat. He was again wounded in early September and fatally shot later in the month. During his four months in Vietnam, Breeden suffered three wounds. The family now has the three Purple Hearts and a number of other medals awarded him posthumously by the marine corps.

When Bobby Breeden was killed, the bullet also entered the hearts of his family and friends; it takes more than time to heal wounds left by such a loss. There is a need to understand, to find and accept reasons for the death, assign it a purpose and go on. For the survivors of those who died in Vietnam, it is not easy to find acceptable reasons for the sacrifices. The wounds are not clean. Healing isn't certain or easy.

Bobby's personal reason for fighting in Vietnam was simple: he wanted to go. He felt that it was his duty.

"He said that he believed in what the United States was doing, and he felt like he was going over there to fight to preserve freedom for his child. He felt that that was his place, and to keep it out of the United States, that more people, more of the men, ought to be over there fighting for freedom.

"It's all — it sounds ridiculous. When you look back on it, you think: those boys went over there and they thought: 'I'm going to fight for freedom to keep my children and my family and my home free.' You wonder if it was really worth it."

The usual distance between the individual citizen and the business of the military was shattered when Bobby was killed. Teresa now wanted to learn more about the war, talk about it with relatives and friends. When she tried, she discovered a great silence and experienced a subsequent feeling of alienation: "I remember thinking that people weren't talking about the war, and I always thought, well, they're not talking about it because of me. They didn't want to say anything in front of me. Maybe that wasn't so, but it was just the impression that I had.

"Every once in a while, I would try to start a conversation, but then they, somehow or other, would always try to sort of change the subject."

A number of times Teresa felt set apart by silence because of her status as a war widow: "I remember one time in particular when I first went to work where I'm working now for the national guard. We had a national guard general come through. There were only two women in the whole building. The other girl that worked there, her husband had been in Vietnam.

"I remember that it just made me feel really bad that day because he [the man we worked for] introduced her and said something about her husband was in Vietnam. He was in special forces, all that. And then he said, 'This is Teresa Breeden,' and he just kept right on going. Just like he didn't want to mention that my husband had died over there because he was afraid he was going to put a damper on everything."

The impact of Bobby Breeden's death is only part of this family's relationship with the military. Like thousands of Americans, Teresa depends on employment in a branch of military service. Although she and her two children collect a small compensation for Bobby's brief time in the service, the major portion of the family's income is from Teresa's job.

In the early 1970s, Teresa got a civilian job with the national guard. Shortly after she started working, the guard began accepting women as members.

"My sister and I got to talking about it. Of course at the time I needed the money. I needed some extra money because my GS-4 salary wasn't very much. Most of the higher-paying jobs, you have to be in the national guard to hold the jobs. So, I figured, well, this is my way to get a promotion."

She has now been employed by the national guard for 11 years. She has received several promotions and bought a house.

Even though Teresa feels strongly about her responsibilities in military service, her feelings sometimes conflict with her responsibilities as a parent. In these moments, the complex nature of her relationship with the military, its policies and organizations, is evident.

Teresa Breeden is now a single parent supporting two teen-aged children: a 15-year-old daughter, Stacie, and a 14-year-old son, Bobby. Considering the obstacles, Teresa can be extremely proud that she has made a home for her children. But she is disappointed by the recent cuts in the social security benefits of her children.

"It's a real sore subject with me on the social security, it really is. When my children turn 18, they lose their social security, whereas we were promised that until they were out of college, and now they won't get it anymore. They will probably get some help through VA [Veteran's Administration] compensation, but it's not anything like the social security check that was supposed to come every month.

"Obviously, being on my own, I don't have a lot of money saved for them to go to college. All these years we've been counting on social security and VA. I've worked all my life. I've been working ever since I was 16 years old, and I've worked hard to raise my kids. I think it's something that the government owes them.

"And I think it's a shame to do what they're doing: to build all these nuclear weapons. They could do away with one nuclear weapon and probably send half the children in the United States to college with the money from that!"

In addition to their support and education, Teresa is responsible for the guidance of her children. On the subject of military service, it is particularly tough to give her children information and advice. Her own opinions are not clear to her. Her thoughts and notions of patriotism conflict with the desire to keep her children from harm. Bobby, her son, has already expressed an interest in the service. The confusion Teresa feels is evident: "Not too long ago Bobby said something about joining. I told him, 'I wouldn't really want you to go, but it would be your choice.' I said, 'You're the sole surviving son. You're the only one left to carry on your father's name, so you really wouldn't have to, but if you wanted to, I wouldn't stop you.' If it came right down to Bobby, I couldn't make him not go. I got to let him do what he thought was best.

"I can't really tell him what it's like, because there's definitely a difference in being a female in the military and being a male in the military. There's a big difference in being in the national guard and being in the army or the navy or the marines. I don't know that I would recommend that he go into the marines. Course, then again, my father was a marine, my husband was a marine."

It has not been easy for Teresa to raise her children without a father. She knows they are sometimes silent about who their father was and how he died. The implications of their silence disturb her. She would like them to be proud of their father, but it is very difficult when so much controversy continues to surround the conflict in which he lost his life. Most of the U.S. casualties were very young men. There had been little time in their lives to achieve anything else for which to be remembered.

Teresa believes that this confusion of emotions influences the education of her children. "I really think that the kids Bobby's and Stacie's age have had so little involvement other than the fact that Bobby knows that his father was killed and Stacie knows that her father was killed. It's almost like everybody is kind of trying to say, 'Well, maybe if we don't teach them about it, if they don't learn about it, they won't think about it.'"

When Teresa thinks of the sacrifices of that period, her feelings are not clear. On one hand, she is proud of her husband, "the way he took it upon himself to volunteer and not to wait for somebody to come and say, 'It's your time, you're going now.' Instead, he said, 'This is what I think I ought to do, and this is what I think is right, and this is what I'm going to do.'" But she also feels bitter and sad, "Just sad about it all. So many young people lost their lives. Every once in a while. I look back on it and really just don't know what to feel."

''There is nothing, except a tragic death wish, to prevent us from reordering our priorities, so that the pursuit of peace will take precedence over war. " — Martin Luther King, Jr.

Tags

Sarah Wilkerson

Sarah Wilkerson is a free-lance writer living in North Carolina. (1983)

Sarah Wilkerson is a graduate student in American history and is particularly interested in oral history. (1982)