Teaching Behind Bars

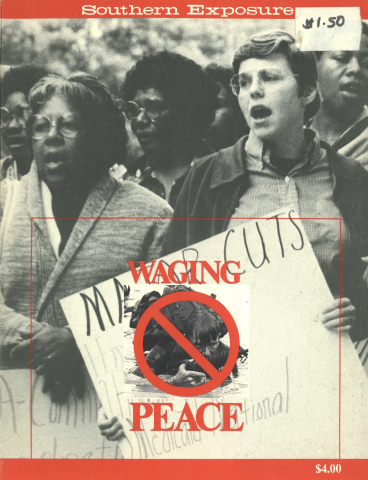

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 10 No. 6, "Waging Peace." Find more from that issue here.

C. Edward Perkins is a writer and editor in Clinton, NY.

COLUMBIA, SC — Crime and its costs — to the victims, to society in general and to the criminals themselves — are a major source of fear and worry for the citizens of this country today. What points certain people towards a deadly cycle of destructive behavior, degrading jail terms and more crime? The theories vary as widely as the background of the experts; but James Cantrell — an inmate at the Watkins Pre-Release Center in Columbia — believes that for himself, at least, one answer is lack of education. And as developer of adult literacy programs at Watkins and at South Carolina's Central Corrections prison, he's been acting on this belief to help himself and other prisoners.

Cantrell dropped out of school in the ninth grade, and after a successful stint in the navy was in and out of prison for several years, never able to keep a job for long. Then his downward spiral bottomed out: he was sentenced to life imprisonment for killing a man in a barroom brawl.

Angry and bitter, Cantrell entered South Carolina's Central Corrections Institute in 1975. Soon afterwards, he began reshaping his life. From inside the prison walls, he fought for and won a high school equivalency diploma in 1976 and went on to take a bachelor's degree from the University of South Carolina.

"There came a point in my life," Cantrell says, "that I realized my lack of suitable employment was connected directly to my lack of education. I decided I had better turn things around."

Cantrell blossomed in his newly discovered academic environment. He became president of the prison's USC student body; he published articles, attended workshops and was elected inmate of the year. But he was shocked by the huge numbers of other prisoners who had never learned to read or write. He began to see them as being imprisoned as much by their lack of communications skills as by the prison walls. Many, he said, needed help simply to write a letter home to their families.

Becoming more and more concerned with adult basic education, Cantrell helped organize Central Correction's first classroom for illiterates. "It made sense," he says, "that I was being given help, and that I should pass this on." The classes met in a basement tunnel where, Cantrell recalls, "We had to work around guys who were sweeping and mopping and turning over buckets of water on our feet. But we managed and we survived."

Soon prisoners interested in improving their language skills lined both sides of the tunnel. Cantrell's group trained more tutors and eventually gained access to better facilities. The prison authorities began to recognize the program's value and slated it to become part of a modern educational complex which was just being built when Cantrell was transferred to the Watkins Pre-Release Center in 1980. (The complex is now complete.)

Because of his background, Cantrell was assigned as assistant administrator to the Watkins education department. Yet he was allowed to teach only four hours a week. "This was very frustrating," he says. He negotiated with the authorities to improve and expand the program and began offering classes five days and four nights a week. He recruited tutors and students and developed contacts with agencies outside the prison — including a volunteer literacy organization which now helps train about 18 prisoner-tutors each year at Watkins.

Thanks largely to Cantrell's leadership, the Watkins program now teaches basic literacy skills to up to 45 prisoners at a time. In addition, staff and inmates hold Adult Basic Education classes geared towards high school equivalency diplomas, and a college extension program is also available. Cantrell and the other inmates — as well as the prison authorities — feel that the literacy program at the pre-probation institution increases the odds for a successful life outside the prison walls.

Cantrell is proud of the programs he helped develop at Central Corrections and Watkins and hopes he can help make further improvements. Already, the idea of prisoners tutoring prisoners is spreading to other South Carolina prisons.

Cantrell plans to continue teaching and developing educational programs even after his release. He is currently completing work towards a master's degree in adult and community education and has already begun teaching college courses outside the prison in a work-release program.

"This is what I want to do the rest of my life," says James Cantrell. "With some help, this is what I will do."

Tags

C. Edward Perkins

C. Edward Perkins is a writer and editor in Clinton, NY. (1982)