This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 2, "Neighbors." Find more from that issue here.

EAST POINT, Fla — Seventy-eight-year-old Joseph Lolley sat in his boat shed reminiscing about his boyhood. Dressed in blue coveralls and white T-shirt, he looked more like a simple farmer than the boatbuilder whose name is legend among local oysterers and whom younger boatbuilders call "the best there is" in the region.

Joseph Lolley started oystering with his father when he was five or six years old. "I became so fast," he said, "I could cull faster than my father could tong!"

In those days oysters were sold by the thousand, and the wagons, driven by mules, oxen or horses, would come down during the winter months to cart them to Atlanta or other northern markets.

Located in Franklin County, on the Gulf Coast between Tallahassee and Panama City, East Point is the hub of the local oyster fishery, which last year produced 92 percent of Florida's oysters. Here the confluence of the Apalachicola River and Apalachicola Bay makes the oysters both plentiful and delicious. "The fresh water makes the oysters fat and the salt water makes them tasty," one oysterer explains.

Today oysters are sold by the bushel or gallon, and refrigerated diesel tractor trailers rumble in and out of the 16 independent shucking houses along East Point's bustling waterfront, transporting oysters year-round to destinations all over the United States.

Though refrigeration and mechanization have modernized the processing of oysters, the harvesting is still done as it was when Joseph Lolley was a boy: the tonger scrapes the oysters up from the bottom using a pair of long wooden-handled tongs, and the cullers sort through them, breaking up the clusters and tossing the undersized oysters overboard.

Of the 3,400 people employed in the East Point oyster fisheries, about 700 are full- or part-time tongers who ply their trade in the unique boat that Joseph Lolley helped develop.

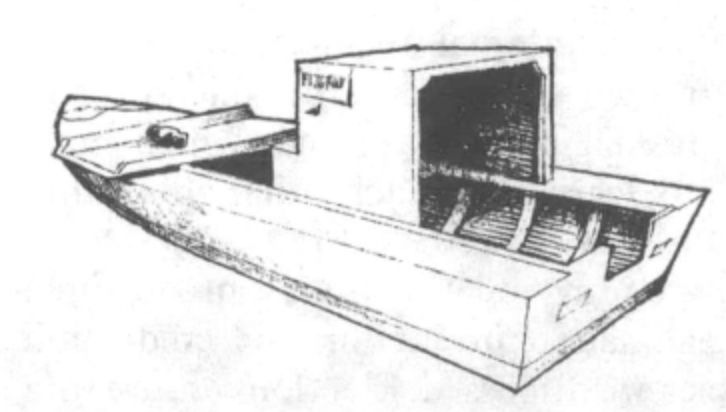

Distinguished by a sharply upturned bow, wide side decks, a box cabin or "dog house" on the stern, and an outboard engine, this type of oyster boat is especially well adapted to its working conditions. It serves as a stable platform for the tonger standing on the side decks, provides shelter for the crew from sudden changes in weather, and carries up to a ton of oysters in sometimes choppy seas.

Like other traditional American working craft, the "Lolley boat" has evolved to suit a region's particular circumstances (weather and water patterns) and cannot be found in other areas.

Lolley has built boats for a livelihood since his youth. He learned his craft from his father, whose sturdy boats were among the few to pass the rigors of government testing and were used by the Coast Guard during World War I.

Joseph Lolley also builds boats to last. "To hit a sea with a load of oysters, a boat has to be tough," he says. He learned much from some of Florida's Greek fishers who befriended him. While others moored their boats during hurricanes, the Greeks reefed their sails and rode the storms out. Expert sailors, they knew how to make the forces of nature work for rather than against them, and as a boy Lolley became aware of that distinction, applying it first to the design and construction of his "play" boats and later to his full-size boats. He says he conceived the hull he builds today when he was a boy, running along shore pulling behind him a toy boat improvised from a barrel stave.

When he moved to Inglis, midway down the Florida peninsula, Lolley learned how to build V-bottom boats, and he's credited with introducing this design to the East Point area when he returned about 25 years ago.

While the materials have changed through the years — marine plywood has replaced cypress planking, for example — the "Lolley boat" remains the model for the 300 oyster boats in the East Point fleet. Surprisingly, not one is a mass-produced fiberglass boat. "With age they don't hold up," Lolley explained.

Today, Joseph Lolley only "dabbles," constructing an occasional boat for his grandchildren and instructing the younger builders who seek his advice. He has supplied hundreds of boats to two generations of oysterers, but he seeks no formal credit for his accomplishments, content with the modest boat that he has built "for the working people."

Tags

Richard Lebovitz

Richard Lebovitz is a freelance writer in Buxton, NC. (1983)