To Do What's Right: Interviews by Dorothy Hall Peddle

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 2, "Neighbors." Find more from that issue here.

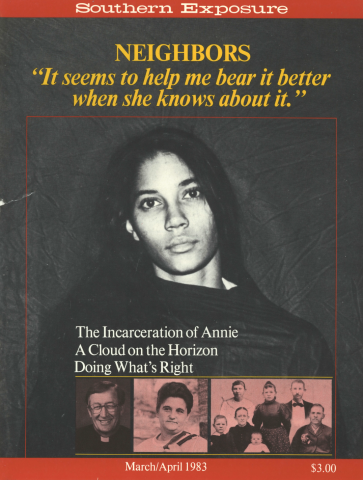

"I've been called a wild woman because of the risks I've taken but never a wonder woman," said Eula Hall of Honaker, Kentucky, founder and supervisor of the Mud Creek Clinic at Grethel. She had been flown to New York City on November 22, 1982, with her husband Bascom to receive one of the 18 cash awards made by the Wonder Woman Foundation to women over 40 from all areas of the country who were judged to possess in an outstanding degree the courage, compassion and independence that characterized the fictional "Wonder Woman" of comic book fame.

In his letter nominating Hall for the Wonder Woman award, Richard Couto, director of Vanderbilt University 's Center for Health Services, praised the work and life of Eula Hall:

"The achievements of Eula Hall are recorded in the lives of thousands of people — men, women and children — who live in the Mud Creek region of Floyd County in Eastern Kentucky. Mud Creek is isolated by horseshoe-shaped mountains and the Big Sandy River and stands out as an area of need, even in Appalachia. Eula was born in neighboring Pike County and has spent her adult life working to meet the needs of the people on Mud Creek. Chief among her achievements is the Mud Creek Health Clinic, which has provided health services previously unavailable to 14,000 patients. [See Southern Exposure, Summer, 1978.]

"Eula began organized efforts to improve conditions in Mud Creek as part of the War on Poverty and was a founding member of the Eastern Kentucky Welfare Rights Organization in the late 1970s. Asa leader of this group she helped acquire hot lunches for children in the Mud Creek schools and gained from state and local government a concrete and steel bridge to serve Mud Creek. This bridge replaced one of Appalachia's most notorious, rickety 'swinging bridges' that school buses had been using to the extreme anxiety of local parents. In addition, she played a major role in acquiring federal and local grants for a water system for the Mud Creek area.

"Most important is Eula's work to provide health care for the needy. She has devoted the last 10 years of her life primarily to the establishment and maintenance of the Mud Creek Clinic. As a social worker and clinic coordinator she provides transportation for those who need it and even delivers medicine to patients when necessary. She insists that everyone be seen regardless of ability to pay. She assists each individual patient with health and legal matters such as acquiring social security or black lung benefits, thus combining the best of paralegal and paramedical roles.

"The significance of Eula's achievements in building the Mud Creek Clinic go far beyond her individual role. Her fire and determination have inspired others. Many of the original staff who founded the clinic in 1971 are still there. Money is certainly not the reason. Salaries are very low, even for Eastern Kentucky. It is determination, the sense that the clinic team is providing something crucial to the lives of people, that keeps them there. Each patient is treated with dignity and respect, and they express a fierce loyalty. The clinic has become a center for community organizing and citizen participation in issues affecting other parts of the mountains.

"Eula has chosen to live where she is considered an adversary of those who have taken from the poor and of those who, while charged with the welfare of others, have lost the sense of injustice. She maintains a sense of outrage. She has no formal training for her work, only the constant abiding principle, 'To do what's right.' Eula often sizes up a situation and concludes, 'Now that ain't right.' Those words are a call to action. She explains more than two decades of confrontation and struggle with a shrug and an almost casual, 'You just get tired of being pushed around. '"

Upon receiving a Wonder Woman cash award of $7,500 at the Ritz-Carlton Hotel in New York City in November, 1982, Hall said: "The best part of it was knowing that women had been recognized for their efforts and that many of them had had the same or similar struggles as I have. "

What follows are transcripts of taped interviews with Hall (with added comments on the health delivery system from a 1981 videotape, "Come Hell or High Water, " by Vanderbilt University's Center for Health Services) and with Mike Sheets, a nurse-practitioner on the Mud Creek Clinic staff.

Eula Hall

I was born and raised in Pike County, Kentucky. I was my dad's first child by his third wife. My father was a healthy, sturdy person, but he couldn't work in the mines any longer because of his age. He farmed and provided timbers for the mines. What we ate was what we raised and generally we had enough for ourselves and enough to give to neighbors when they were in need, like in the spring when supplies would give out and we had extra sacks of peas.

I didn't go to school till 1 was nine, because we lived far out at the head of the holler. When we moved so we could go to school there were three of us starting at once — myself and an older half-brother and half-sister. My first dress was a blouse made from a flour sack and a skirt made out of a yard of chambray shirting goods. I sold herbs to get the material for making the dress. I went to school barefooted and my feet would get so cold by the time I got to school that I just couldn't stand them down on the floor. I remember crossing my legs and sitting on my feet in my seat. I guess I must have looked like a frog. The teacher gave me a whack and told me to put my feet down. We didn't go to school very long that year because all of us got whooping cough.

Things got hard at home and as soon as I could, I wanted to be on my own. By that time there were three brothers under me that were just like my children. I wanted to be able to help them more so they could stay in school. I started working out as a hired girl. I left Pike County and came over to Floyd County where I had a half-brother. While I was taking care of his pregnant wife, I got a reputation for knowing how to care for babies and women and for being a good cook. If I was working where the mother was sick, I would take care of the kids, feed them and do extra things for them.

I met McKinley Hall when I was 17. It was his aunt I was working for. He'd been in World War II and had developed a small disability in the service. In fact, he had had a mental breakdown. He was working the mines before I married him, although after awhile he just quit working. I said I would marry him because I thought it would be easier for me, but it was worse. I found there's worse things than being a hired girl. I had always seen the good side of my husband and never the bad side, but after we had been married for two weeks he started drinking and became very abusive. I think it hurt his pride that he wasn't able to control his wife. He was a man who didn't want you to think for yourself, but I just had to think for myself because I'd been on my own since I was 12 years old.

My first husband was very violent, very abusive both to me and to our children. He would beat me, tear my clothes, set the curtains on fire. He broke my ribs, and my cheekbone three times. Once my eyeball was even out of its socket. The children would try to protect me and then I had to fight him to defend his children. He was hard on my deaf son Danny. When he threatened us, I would go out to the neighbors for help and sometimes we would have to hide under a house through the night.

That's the reason that I feel now that I owe the community my life. If somebody gives me a call in the middle of the night and she says she's into trouble there's no way I can go back to bed and go to sleep. I advise them — get them to a neighbor or sometimes even my own house or, during the day, here to the clinic. I've taught women to drive. We have classes here twice a week where teachers from Mountain Comprehensive Care prepare women to take the G.E.D. test so they can get jobs at nearby shopping centers and become independent.

As the five children were growing up, I was gardening to feed us and I would take in handicapped people and get paid a small fee from the state. When my husband was around — quite often he was away for a couple of months with some other woman — it wasn't much of a home for those handicapped and sick people, but they said that they wanted to stay with me anyway and not move out.

About in the '60s I became aware of how many health problems were going unattended, especially the problems that affect coal miners. We organized several groups — the Kentucky Black Lung Association, the Kentucky Miners Health Care. We worked with the Council of Southern Mountains, that sponsored the first VISTA workers. And we organized around other issues, like getting better roads and schools, or preventing flooding from silt ponds. Mud Creek in Floyd County has a reputation for fighting for the people's rights. Mostly it was the women. Women will be the ones to protest and to stand in front of the bulldozers.

In Knott County, when stripminers were burying family cemeteries with their dozing, we decided to go and support the old people who owned the land that was being molested. We called it "Save our land and people." We were told the bulldozers that were doing the stripping were coming toward a family graveyard. We got up at four in the morning and by five we were heading for a site.

The guards were hard on the men. They tried to take us on, too, but there were just two men against 22 of us women. Some crawled over the barricades and I crawled under. We had Channel 3 there from Huntington, to document what was happening. When we finally got to the site, we really got on those operators good. They told us we would go to jail for trespassing, but we told them they were the ones breaking the law, covering up fields of beans and corn and just raping the fields. A driver said, "If my mother hadn't been a woman, I'd have shot them all!" But we succeeded in stopping them.

But health care was always my baby, because I've seen so much suffering. The clinic started with the Eastern Kentucky Welfare Rights group, after the screening we did in the summer of 1972. We began door-to- door health screening and found there were more than 14,000 people in the hills and hollows that needed serving. At least one out of 10 needed health care and wasn't able to get it. We found quite a few people who had never seen a doctor in their lives. There were complications of pregnancy, disease from contaminated wells. Diseases like black lung, diabetes and hypertension were going untreated. A lot of people had no vehicles to drive to hospitals at Martin, Pikeville and Lexington or they weren't served when they got there (though Our Lady of the Way hospital in Martin has never turned anyone away when they needed help and couldn't pay). We knew we had to have some kind of primary medical care at Mud Creek.

I never let people forget there were problems that weren't getting attended to. Finally, somebody answered my call. Some concerned people got together and raised $1,400 with rummage sales and donations, and we rented a small frame house in 1972. I was surprising myself and starting a clinic! We got two doctors from Our Lady of the Way to come from Martin two days a week to see patients. With what equipment we could pay for, we had a start. I always had it in my mind that if we couldn't provide full-time health coverage, we would at least have a center where everybody could come and people would be made aware of the problems.

Before very long the first clinic was too small. So I moved out of my house and the clinic was put there in 1974. We divided the rooms and closed in the back porch for medical records and lab and the front porch for examining room and lounge. Later we added a unit for respiratory therapy. We had begun to get monthly waivers of $5,000 from the United Mine Workers for testing for black lung disability and for therapy. We were expanding staff and services and doing well by 1977, when the clinics with the UMWA waivers were informed that those funds had run out and that we would need to look for other funding.

So we went to Big Sandy Health Care in Prestonsburg, the funding agency that works out of the Appalachian Regional Commission in Atlanta. They agreed to a merger, so we could keep serving people on a sliding scale, doing our own hiring and getting personnel through Big Sandy as well as their administrative services. It was the best thing that could have happened to Mud Creek Clinic. But it was good for Big Sandy, too. It has to be the people that shows the medical folks and politicians that something can be done.

In the clinic at Craynor on the Mink Branch we had 19 rooms and two beds. We had a dental clinic. We had 20,000 patient records, all in metal file cases. All of that went up in flames on the night of June, 1982, when I got a call that the clinic was on fire. They think it might have been drug thieves trying to cover up a theft. We called the Mud Creek Volunteer Fire Department, but the truck stalled. When we got there, we could see nothing could be saved.

I went back home and thought about the destruction and I just had to cry. I thought and I cried and then I thought some more. I talked it over with my husband Bascom, no relation to the McKinley Hall who had died about eight years back. Bascom and I decided we would have a Mud Creek Clinic, come hell or high water! We got back there early next morning and some of the medical staff were on hand too. The women were crying and asking, "What are we going to do now, Eula?" I said to them, "We're going to see the patients. That's what we're going to do!"

So we told the Harold Phone Company to come out and hook up a phone so we could reach the patients and tell them we were still in business. At first they told us it wouldn't be possible. Then Bascom's cousin Eric, out on a phone company truck, was contacted by CB radio and within a half-hour we had a phone being installed on the willow tree near where the clinic was still burning.

We got a table and some chairs, and some of the women volunteered to stay at the phone. Our staff saw 20 patients that day. Then we made arrangements with Gary Newman, who was the principal of the John M. Stumbo elementary school a mile away, and by five that afternoon we were getting moved into the school and gradually getting the equipment we most needed from hospitals and from our sister clinic in Magoffin County. Mike Sheets can tell you how we got our trailers for the clinic we're in now, and began over again here in Grethel in August after spending the summer in the school building.

My plans are to have more and better services. We're going to have x-ray facilities. Dental is a great need and it's very possible we can get a dental unit and can get a dentist through the National Health Corps. We're going to have a big room for community meetings and education classes. We hope to have evening and weekend hours if we can get more staff. I think these trailers could be used for staff housing.

What I hope and pray for is that we can have an abuse shelter for women located somewhere, maybe not with the clinic, but with police protection. It's a great need. Just recently a disabled woman near here shot her estranged husband, who was battering the door down, because she thought she had no choice. The courts will always stand by the man. You can imagine what it would mean to a woman like that to have a place to go for even temporary protection and to get a good night's sleep.

I've fought hard for a place where patients can be treated as people. It has to be accepted that health care is a right and not a privilege. A third of the people cannot afford the full cost of their health care. I believe that financial incentives should be away from more expensive kinds of care and toward less costly forms, where money can be saved through wise purchasing and a dedicated primary care staff. We need to have federal intervention in remote areas like this.

I've said often that the health care delivery system is a reflection of what we value as a society. Do we really care about people? If we don't, it's society that's going to suffer!

Mike Sheets

I am a family nurse-practitioner, a commissioned officer with the U.S. Public Health Service. The only way I ever got an education was by getting into the armed services. My family was poor, dirt poor. In school they told me I would never get anywhere because I was from the wrong side of the tracks. When I went into the army I found I couldn't qualify for the education to be a gunnery pilot. They said they did have an opening for surgical technician and I took that. I found out that I liked the work. When I got out I entered nursing school. My grades were high, but I ran into prejudice from the faculty because I happened to be male. Then I went on and got my master's degree as nurse-practitioner from the University of Tennessee in Knoxville.

Mud Creek Clinic is a good place to work, because we work together. I'd rather be out here in the country than be in the city where you have a pecking order and everyone is stepping on each other's toes. What we do in a primary health care clinic is to treat things that are easily treated and manage chronic disease to keep it from getting worse, besides making referrals. What I do as a mid-level medical professional is to suture wounds, deal with infections, treat bronchitis and pneumonia, things like that. I have a good trust-relation with Dr. Ellen Joyce, the doctor in family medicine who's been here since 1978. We also have Dr. Gordon Young, a dermatologist who comes two days a week. Sister Sarah Ragalyi is an R.N. and we have Juanita Compton as L.P.N. Mike Brooks is pharmacist. Eula is supervisor, public relations person, counselor and transporter of patients. For maintenance, we couldn't get along without Bascom Hall, who holds the place together.

We do a tremendous number of examinations to see if people qualify for disability compensation. The system is so screwy. If you're disabled or have got chronic disease and you're poor, you can't even see a doctor to get into the system. There has to be an entry point and that's where Mud Creek Clinic comes in. We do the examination. If somebody isn't really disabled, we'll tell them they're wasting their time and not go any further. And Social Security knows this. They know that when they get something from us, it's the truth.

The poverty is just rampant around here. We have a phenomenal parasite problem because the wells are real low. There's a water system here now but because of the cost, people are reluctant to hook into it. Until a year ago, we had no organized trash collection at all, people just threw their refuse over the embankment and into the creek. After we've given the patients medicine for parasites, usually they're all right for awhile but then it comes back.

We do a lot of counseling and education to try to teach people how to take care of themselves, but sometimes it's a matter of not having any water at all. I had a patient that had an infection in his foot and he was getting blood poisoning. I told him to soak his foot in hot water with borax and he said his well had dried up and so were the neighbors' wells. He hitchhiked eight miles to come to the clinic so we could soak his foot.

Last June with the fire destroying our other building we were real anxious because it looked for awhile like we might not even have a clinic. When I came to the clinic the day after it burned down, there was just the chimney and hunks of metal left. We lost $300,000 worth of equipment accumulated over 10 years' time. One day we had it and the next day we had nothing.

We grieved for a half-hour and then we started making out lists of what we needed. We hardly had more than our personal stethoscopes and ophthalmoscopes, but we saw the people who came. You can't turn people away and say you're sorry. We prescribed medicines, did first aid and saw about 20 patients that day. The administrator from Prestonsburg came out the day after the clinic burned down and said it would take at least three or four weeks before we could be in business again. We told him, "Here's a list of the equipment we need. Get working on it!"

The same day, we went to the John M. Stumbo elementary school at Grethel and talked to the principal about moving over there for the summer. He agreed to the arrangement. We cleaned up the place and we were seeing patients in the school within the next 24 hours. The local hospitals and the Magoffin County clinic were real helpful. They loaned us equipment and we got outdated equipment from the nuclear disaster hospital in the area. There were 75 volunteers who went out to pick up the stuff. They just came out of the woodwork, many of them our own patients.

We don't just have poor patients. We have people from millionaires to those who are broke and don't have anything, because it's the only thing around here, and it's a community clinic.

They discussed fundraising needs at a community meeting held at the school over the weekend. About 400 people from the area were at the meeting, mostly patients and supporters. Over $4,000 was raised and pledged in $5, $10, $20 donations from people who couldn't afford to give it. We were on the air with the station from Pikeville 12 hours a day, two days, in a radio telethon which helped us raise $17,000. District 304 of the UMWA pledged $2,000. Once people could see that we had local support, it gave us help getting other monies. The Catholic bishop at Covington gave us $10,000. The Dominican Sisters from Racine, Wisconsin, raised $5,000 for us. A lot of coal operators and businesses contributed, too.

The other thing that speeded us up with getting donations was that federal funding in all the clinics was changing on October 1 from 20 percent local to match 80 percent federal, to a 50-50 percentage basis. There's no way we could have raised $200,000. We just slid in, we barely made it, so we could get a $320,000 Appalachian Regional Commission grant by matching it with our $80,000. The ARC got us a double-width trailer all the way from Irvine, Kentucky, one that two pediatricians had been using. We had to get another HUD trailer ready for pharmacy occupancy by August 15, when we would have to vacate the school building. To get the pharmacy trailer ready in time for the move, we worked day and night. There was Bascom Hall, Mike Brooks, myself and volunteers who helped with the floor, carpeting, wiring and insulation and lighting. All the lumber was donated.

I think the main reason that this clinic is still in business while they closed two others in the Big Sandy system is that the need here is so great and we have such good support in the whole community. Our business here has picked up from seeing 25 patients in a day to seeing 75, just with the change of location to Highway 979. At Mink Branch, roads were broken down from trucks and it was always muddy. There was no decent place to park. The buildings were old and leaked. Here at Grethel on the Mitchell Branch we have good level ground and it's convenient for people to reach us. We're extremely happy with what we've got. People who come in from the outside and are used to chrome and leather chairs are appalled with our old furniture. But it's so much better than what we had.

I'm proud that Eula was selected to win one of the 18 Wonder Woman awards from so many hundreds recommended in the nation. I think it's one of the few times somebody got an award that was justified.

Tags

Dorothy Hall Peddle

Dorothy Hall Peddle is a communications person and freelance writer. She resides at the Siena Center of the Sisters of Saint Dominic in Racine, Wisconsin, where she is Sister Helen Peddle. (1983)