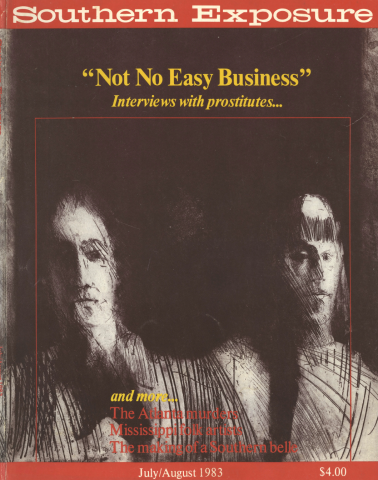

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 4, "'Not No Easy Business:' Interviews with prostitutes." Find more from that issue here.

MONTEZUMA, Ga. — Southerners don't just casually enjoy their vegetables. They love them dearly and defend them passionately. They would approve adding a fifth verse to "America, the Beautiful" in which the black-eyed pea, the collard, and the butter bean received their due share of choral praise. And . . . maybe . . . with reservations . . . okra.

Okra is at once the most relished and most despised of the vegetables called Southern. By no means a "new" vegetable, it arrived with the first Africans to land on our shores. As they struggled to recreate on their rough new hearths something of the taste of home, okra became a favorite (with some) in cabin and big house, lending variety to the corn, potato, bean, and turnip cuisine of the farming frontiers.

Okra is now working its way North. I have reports from spies who say that in Chicago they have eaten young okra pods battered, deep-fried and dipped in mayonnaise. In Wisconsin you can get it dilled (as in pickle) — and in New York City, much to the surprise of a Greek-American Boy Scout visiting from Atlanta, it was built into a moussaka. "Jeeze, Mom," he protested, "eggplant and okra!"

Like the egg and the avocado, okra comes in attractive little packages. In France according to LaRousse Gastronomique, the pods are sometimes called "ladies fingers." The word "gumbo," used for a sort of stew that incorporates seafood, ham, chicken, tomatoes, onions, and peppers, is actually just another West African name for okra. The plant belongs to the mallow family and grows all over Africa and India, where, since earliest times, it has been cultivated as a garden vegetable.

It is the mucilaginous quality of okra that, for some choosy eaters, puts it beyond the pale. If boiled only a minute too long it disintegrates into a slippery mess. In gumbo this is a desired quality; it makes a thin stew into fork food. But by far the most popular way of preparing okra is to slice the pods into half-inch rounds, shake them in a bag with salt, pepper, and Southern cornmeal, and fry them in bacon fat.

What fast food chains have done for the potato and the cabbage, through offering French fries and slaw, they may yet do for fried okra. In the Macon area several truck stops near the Farmer's Market sell "Fried Okra Snacks" by the paper scoopful.

Retired Southern executives tend to go in for kitchen gardening, and invariably include a half-dozen okra plants. Accompany such a hobbyist on a pea-picking tour and he will always stop by the okra patch, take out his pocket knife and carefully cut off a few tender young pods.

He will reminisce, "Mama always cooked a little okra along with black-eyed peas — she said it gave them flavor. Then she would lift the pods out and put them down on Papa's plate, along with his peas and rice and his chopped onions and pepper sauce." Now he is Papa, and his wife indulgently lays the okra over the peas when she cooks them. So, in small ways, we reconstruct our personal pasts.

It has always been a puzzle to me that some vegetables are funnier than others. Take corn. Wheat and rye and barley are never comic, but corn is hilarious. Cucumbers are sober vegetables while squashes bring chuckles. Rutabagas and parsnips are amusing. But, as an ingredient of Southern ribaldry, okra takes the prize: "Play that okra song — 'Slip, Slidin' Away!"' Or, to a child whose socks have fallen over his shoe tops, "What's the matter, kid? Been eatin' too much okra?"

One thing can be said for sure about this eccentric vegetable.

No one will ever dump a can of cream of mushroom soup over it and call it "lady finger casserole."

Tags

Violet Moore

Violet Moore is a writer and librarian in Montezuma, Ga. (1983)