What's Happening in Atlanta

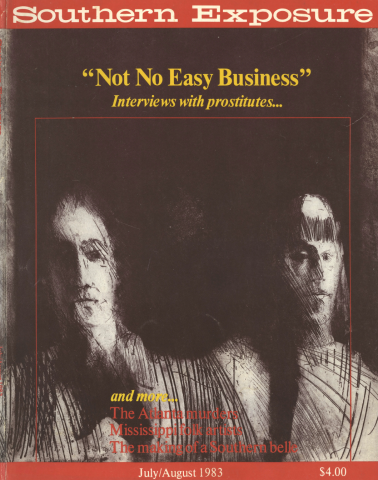

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 4, "'Not No Easy Business:' Interviews with prostitutes." Find more from that issue here.

Atlanta earned the affectionate nickname ''little New York" from blacks who bought the image of it as "a city too busy to hate, " a mecca for black millionaires and a model for the New South. But a series of murders and abductions of black children, which first drew public attention in the summer of 1979, transformed Atlanta into a city of terror.

A year after the first body was discovered, an official Atlanta Police Department Task Force was finally set up in response to growing public outrage at the police indifference and the apparent class bias of Atlanta's black leadership toward the murder of children from poor, inner-city neighborhoods. Official figures claim that 29 young people, mostly boys between the ages of nine and 14, were murdered in the July, 1979, to June, 1981, time period. Wayne Williams, a black photographer, was arrested in June, 1981, and charged with two of the murders. He was convicted in February, 1982.

The Task Force was disbanded after Williams ' conviction and authorities were reportedly satisfied that Williams was guilty of at least 24 more of the murders. The verdict is being appealed and the defense is expected to use information about the other murders that took place throughout the three-year period, particularly those that took place while Williams was in custody. Before, during and after the trial, a number of community forums focused on the discrepancies between "official" and "actual" versions of events surrounding the abductions and murders. There were community protests around the arrest, trial and verdict in the Williams case and the disbanding of the Task Force.

The black parents of Atlanta, who were primarily responsible for bringing the murders to public attention, organized their own campaign to stop the killings. Despite enormous public and personal pressure, the black community has continued to keep count of the dead. Many other girls, young women and young men have also been murdered, but excluded from the official death toll as not fitting the arbitrary "pattern" established by public officials. A number of families have petitioned the Attorney General for an investigation of the murders. The chief of police, in response to continued community and national pressure, invited a citizen's task force to assist in investigating the murder of seven women. Community forces hope to use this opportunity to reopen the entire case.

This article is taken from the prologue to Toni Cade Bambara's forthcoming book on the Atlanta murders (to be published by Random House).

You're on the porch with the broom sweeping the same spot, getting the same sound — dry straw against dry leaf caught in the loose-dirt crevice of the cement tiles. No phone, no footfalls, no welcome variation. It's 3:15. Your ears strain, stretching down the block searching through school child chatter for that one voice that will give you ease. Your eyes sting with the effort to see over bushes, look through buildings, cut through everything that separates you from your child's starting point — the junior high school.

The little kids you keep telling not to cut through your yard are cutting through your yard again. Not boisterous-bold and loose-limbed as they used to in first and second grades. But not huddled and spooked as they did last year when those low hanging branches swayed and creaked, throwing shadows of alarm on the walkway. You had to saw off the dogwood limbs then and dig a trench to upend the lawnleaf bags into. They looked, those heaps of leaves, like bagged bodies. You hum now and get noisy with the broom as you come down the steps so no child taking the short cut from the elementary school should get hysterical coming upon your own self in your own back yard. No need. Like adults, the children are acting as though everything is fine now, the terror over, the horror past.

One suspect charged with two murders. Case hanging literally by a thread — dog hairs and carpet fibers. But the terror is over.

It's 3:18. The group across the street that sometimes walks home with your child waves to you. You holler over, trying not to sound batty. They say they waited, shrug, then move on. A bus chuffs by, masking the view and drowning you out. You lean the broom against the hedges and play magic. If the next three cars that stream by sport one, just one, bumper sticker saying, "Help Keep Our Children Safe," then all is well, you figure irrationally. You wait out five cars, a mail truck, and a moving van before you spy a tattered sticker on an out-of- state camper saying "Help . . . Chil" in a weather-worn way. You run to the curb to hail a cab, though that makes no sense. A cab can't travel the route your child takes from school, can't cut through the projects or jump the ditch back of the fish joint. Plus, you're in your slippers and your hair looks like a rat's nest.

You run inside to phone the school. The woman tells you that there is no one in the building. You point out the illogic of that, an edge to your voice, and ask her to please please check, it's an absolute emergency. You can tell by the way she sucks her teeth that your name is known in that office. You've been up there often with your mouth on fire about certain incidents they call "discipline," you call "battering." You stalked the coach around the gym one sunny afternoon, a basketball in one hand, a frying pan in the other — visual aids for your clenched-teeth recitation: See now, Coach, this ball is what you're supposed to be about and this kitchen pan is supposedly what I'm all about, and if you don't quit beating up on these children. . . . He backed off in that sickening way that told you why his colleagues appointed him the Beast-in-Residence and why he went for it. Things weren't bad enough in Atlanta — the children, the community, the city in a panic — teachers were setting up hit lists, or "lick lists," as the Beast kept saying, backing into the ping-pong table asking, since it wasn't your child sent to him for paddling, what the hell is the matter with you?

What's your problem, the principal wanted to know when you broke up PTA last fall to demand some security measures. Not enough books to go around, the children stay after school to play catch-up in the library or lend-me on the stairwells vulnerable to a kidnap attack. The men elected to organize defense squads. But the principal said, "There will be no vigilante groups in my school!" City under siege. Bullhorns bellowing, "Stay inside!" Armed helicopters beating overhead. Young curfew defiers rounded up and hauled down to the Task Force office and badgered to confess to murder. Atlanta a magnet for every amateur sleuth, bounty hunter, right-wing provocateur, left-wing adventurer, do-gooder, soothsayer, porno film maker, crack-shot supercop, crackpot social analyst, scoop journalist, paramilitary thug and freelance fool. But there will be no bats and sticks in his school. So you went right off to nut city, cause the children have a right to some safety, good dreams. They've a right to childhood. They've a right to their lives. "Unladylike," the librarian whispered to the hygiene teacher. But how do you conduct a polite discussion about murder?

The woman, back on the phone and surly, tells you once more that no one is in the building. You tell her your name again, say you're calling from home, mention the time, insist she write it down. You hang up and interrogate yourself: Why did you do all that? Establishing an alibi in case something is dreadfully wrong?

The families of the missing and murdered children were subjected to interrogation, lie-detector tests, to media's sly innuendo at first, then blatant and libelous accusation. In December, 1980, parents were called in again to face the polygraph. Mr. Bell, father of Yusef, and a friend of Latonya Wilson's family were suspects for more than a year. Vera Carter, mother of Anthony Bernard Carter, was arrested, then released but grilled for two months. A young, poor black woman with only one child, one child? Highly suspect. And every so often the authorities leak little poison-pen messages — the parents are not above suspicion. Usually the FBI. Usually about the more outspoken critics of the investigation. You've noticed the pattern. You've kept journals for over two years. Whenever members of the Committee to Stop Children's Murders (STOP) speak around the country, marshalling support from groups ready to launch a mass movement for children's rights, the FBI goes into the parents-did-it number. Murderous parents, street-hustling hoodlums, and the gentle killer — the official version of things. In spring, 1980, just weeks before STOP's May 25 rally in DC, FBI agent Twidwell said to a civic group in Macon, Georgia, that in several cases the parents offed their kids because "they were such little nuisances."

You'd hoped that the parents would follow through with the defamation suit. You'd hoped that the DC rally would lay the groundwork for a National Black Anti-Defamation League with muscle. That the idea of a National Black Commission of Inquiry, discussed after King's assassination, would be put into effect. Were sure a National Children's Rights Movement would be mounted. You've been searching since for meaningful signs.

So. You're standing there with one hand on the phone, trying not to squander precious energy thinking about all those speeches, pep talks, booths, buttons, green ribbons, posters, bumper stickers, profiling, missed opportunities. You need that energy to figure out what to do, who to call. Where the hell is your child?

It's 3:27 on your Mother's Day watch, and you can't go on standing there feeling helpless, scattered, enraged and crazy. Because next thing you know, you too will be longing for "normalcy." And you trust "crazy" way before that. So you snatch up the runner from the dining room table and wrap up your head, kick off your scuffs by the door and step into your clogs, dump your bag on the floor and scramble for key ring and change purse, and take off, running down the avenue like a crazy woman. You are a crazy woman. But you'd rather embrace madness than amnesia. A six million dollar investigation, and after one year — one man is arrested. And all over the city the sermons urge, "Let the Community Heal Itself." Amnesia rolls in like fog to blanket the city. Down come the reward signs. Off the stickers. Eight hundred police withdrawn from the neighborhoods. One hundred state patrolmen returned to highway duty. Road blocks discontinued. Community Watch Networks disbanded. Task Force personnel reduced from 170 to six. The State Consumer Affairs Office goes after the STOP committee to muzzle and disperse them. Judge Clarence Cooper puts a "gag" order on the suspect, the defense team, his family, witnesses, then literally goes out to lunch with D.A. Slaton.

One man charged with two murders. Two out of 28 on the Task Force list. Two out of the 72 on the community's list. Let the community breathe again and return to normal.

You swing around the corner looking for someone to bite. It's 3:34 in the afternoon and a mad mother is running down the streets of southwest Atlanta, and no one is paying her any mind. Less than five months ago, in May, before Wayne Williams drove across the Jackson Bridge and a stakeout officer thought he heard a splash in the Chattahoochie, you would not have been running alone. Your alarm would have sounded throughout the neighborhood. One phone call would have triggered the block-to-block relay. Neighbors, bus drivers, store owners, on-the-corner hardheads would have sprung into action to find your child, a child, our child — even at the risk of being detained or arrested as many had, foiling abductions — but would have dropped all to risk anything — cause when death's been replaced by murder, it's no longer a family affair.

You race past the taxi shed, noisy in your clogs. An old-timer taps on the window and salutes you with a bottle of Coke. You flash him your face, a mask of distress, and point to the clock. It's 3:40. You've no time to see what he makes of this. That you don't hear him coming up behind you is the telling thing. So, he too is asleep on his feet. The infection has spread. Med fly in California. A tsetse fly epidemic raging in Atlanta. But you understand his craving for closure, resolution. He's a cabby.

In spring, 1981, when Roy Innis of or not of CORE held a press conference on the steps of City Hall, Innis claimed he had a witness who positively knew someone involved in the murders. A cab driver; a member of a sex-drug cult of devil worshippers involving some blacks and whites of prominent Atlanta families; a crazed cult engaged in narcotic-running and ritual murder. Once again the police canvassed the neighborhoods. Timothy Hill's folks met with the authorities; they recognized the picture: a cabby seen around their way on occasion. So cabbies, like karate adepts, Vietnam vets, owners of vans with carpeting, photographers who hang around playgrounds, little old ladies who maunder about in school yards, weirdos dressed like clergy and clergy, blind people tapping along the pavement signalling need, odd religious types, and cops — anybody who can lure or snatch a child to her or his death — start shrinking in size, playing invisible, until the Task Force issues an all-clear bulletin — Innis not credible, witness not reliable, information unrelated, cabby not a suspect. But several "independent" investigators persist in exploring that lead. But the monster's been seized says the media. Cabbies relax.

You jump the ditch back of the fish joint, squinching up your nose against re-fried lard, squinching up your toes to keep your clogs on. And you're wondering, just to keep your mind off the stitch in your side, what effect the pressure to get back to normal had on the families who identified the bodies. "It didn't look like Angel," Ms. Venus Taylor said. "So old, like she'd aged a hundred years in those six days." But the experts said the strangled, mutilated body was Angel Lanier, 12-year-old daughter of Venus Taylor.

"Experts my foot!" said the barber on Gordon Street, one of the customers arguing that anthropologists with just one stray bone can reconstruct a whole dinosaur, reconstruct a whole culture, tell you whether the women of that time wore drawers made of fur, or drawers out of hide. But no one else in the barber shop that day was convinced that there are experts of that ilk down at the county medical examiners. They get a body or some bones, a few teeth, a dental chart or medical record, some ground covering if they're lucky — that is if they arrive on the scene before the APD [Atlanta Police Department], GBI [Georgia Bureau of Investigation], FBI have trampled the site and tampered with the findings — and what do they do, these experts? They talk, drink coffee, jiggle the teeth around in the jaw, take photos, eat tuna on white, watch the clock, look over the Task Force list, and take a vote.

"So old," moaned Ms. Venus Taylor in March, 1980. "It's not my Alfred," said Ms. Lois Evans when the body found in July, 1979, was identified 15 months later as "Alfred Evans," described as having no pierced ear as her son had. "Can't be Timothy," said Ms. Annie Hill in March, 1981, when a body was fished from the Chattahoochie River, for Timothy had been spotted less than 24 hours ago. Mayor Jackson had echoed the report on TV, just hours before Police Chief Napper, head bowed, had to knock on the door with the terrible news. The experts had tagged the water-logged, decomposed body "Timothy Hill," the 13-year-old who'd not been put on the Missing and Murdered list until 19 days after his disappearance. He'd been dead, the examiners said, for at least two weeks.

Some bodies were so severely decomposed, the parents did not view them. They were given pouch burials: embalming powder sprinkled over the remains in a plastic bag. Other parents, on hearing that dogs in the woods had gotten to the bodies, could not bring themselves to make the trip downtown. A skull, a bone — Ms. Willie Mae Mathis sent her eldest son in her stead. Many in the community felt that the discouragement of body-viewing was calculated and had less to do with decay and dog-mauling and more to do with mutilation. A rumored Law Enforcement Assistance Administration [LEAA] memo, dated March 8, 1981, described castration in several cases, ritual carvings in others. A mortician's assistant reported in late 1980, odd needle marks on the genitalia of several. In the absence of any sense of public accountability on the part of the authorities, the community grapevine sizzled with possibilities. After Dick Gregory came to town, presenting his theory of interferon-collecting as a paramount motive, Venus Taylor made a point of yanking the sheets back and mincing no words: the head of the penis cut off in several cases, hypodermic needle marks on the penis of others. "No mutilation," the authorities insisted.

You veer around a dog lying on the sidewalk, asleep or dead you've no time to find out. You dare not look at your watch in your haste. Several boys from the high school are already shooting baskets in the projects. You wish you could hang around for a dunk or two. Wish you could think about something other than what grips you.

"Those bones are not my child." You feel for that mother shivering in the cold basement room of the county morgue, a bundle of bones in a steel drawer, a tag on the toe bearing a name that used to resonate in the park, soar over rooftops on summer nights of kickball, a name that used to ring out staccato-like to bam-bam accompaniment on the bathroom door for hogging all the hot water. The family urging Mother in hushed tones, teeth chattering, to stop holding out for a miracle now squashed. The social worker back at the house explaining that Mother is practicing denial, one stage in a heart-rending process from fear to shock to rage, guilt, denial, grief, release and healing. A friend of Mother's folding the laundry argues knowingly that the silent phone caller can't be the boy, just some crank getting his jollies. The mayor, commissioner, police chief come by to offer condolences, assuring Mother that the city will pay for the burial. The minister says no matter how Mother feels, it's somebody's child down there on a slab and there must be a funeral. The media with lenses and pencils and tapes hold a light meter up to Mother's face and ask what she'll wear to the event. Friends and kin come by to drop money in the plate and no one asks to see the books or the accountant or the license from the Georgia Consumer Affairs Office permitting the family to accept the offering. Neighbors set dishes of food on the table and pay their respects. All have lived through the horror with Mother, but now they want relief, release, a return to routine. So claim the bones, Mother. Have the funeral, Mother. Close the lid, Mother. Let the community breathe again.

One suspect, jailed. Two counts of murder, denied. Cameras barred from the courtroom, there've been enough skeletons on view. Let the community sleep again.

You're stepping through the high grass in the vacant lot one block from the school. You're on the lookout for dog shit, rats, snakes, and broken glass. You are systematically ignoring the pain in your side, the hysteria swarming like nausea, not to mention the bags of junket jiggling in your upper arms and thighs. You're out of condition. You miss yoga sessions, dance class, bike rides, walks. For more than a year, your child would not go out after school, even with you, even with you armed to the teeth with pistol, mace, and the Swiss Army knife she bought for camp last summer. You certainly could not leave her home alone where even the TV waged war — Be Careful! Watch Out! Trust No One! Killer on the Loose! Mental hygienists lamenting loudly — "A whole generation will grow up distrustful, withdrawn, permanently damaged." The media having a field day with reports on black pathology — past, present, future, imagined. "It's 10 o'clock!" blares the TV, "Do you know where your children are?" Hell, it's been 19 months, do they know where the murderers are?

Nineteen months. Scores of boys, girls, young men and women slaughtered. The Task Force office, the Mayor's office, and the media saying over and over the terror is past, the murders have stopped now that Wayne Williams has been jailed. But the word on the block is that at least four boys have been killed since the arrest, the STOP committee's estimate higher. Killed, found, and quietly buried. Down at the morgue, one worker recites policy for inquirers — "We hold an unidentified body for 30 days. If it's not claimed in that time, the city buries the body and that's it." Another worker says only three bodies of youngsters are known to her, then five minutes later, after a huddle with coworkers, disclaims any knowledge of anything, including her own name. You've seen sketches of white women in the papers with the query, "If anyone knows this woman, please call this number?" But the media's been suspiciously silent about black children found lately. And neither the in-charge- for-the-day worker at the morgue nor the officer down at Homicide will acknowledge the case of nine-year- old Amy Willis, strangled to death weeks ago. "There've been no killings that fit the pattern," is the official word. But pattern, connection, links were the very things denied by the authorities for so long.

You turn the corner, falling out of one clog and twisting your ankle. No sound comes out of your mouth though you pain, for there's a crowd in the street by the schoolyard, a blood puddle, and a book bag you know asprawl by the sewer. It stops your heart. Your lungs squeeze shut. Between you and the crowd of children is a woman you recognize from a Block Parent meeting last spring. She's escorting two cops from their car on the curb to an old Pontiac further on where three very loud, very angry Bloods — cords bursting from neck and temples, gums fiery red — bend a man in a suit back over the hood of the Pontiac. You look. He could be Latin, Middle Eastern, you don't really give a damn. You're busy trying to work the bellows in your lungs.

"Don't touch me," the man is saying, weaving this way and that to keep clear of the fists.

"You didn't even stop to see what you hit," one of the angry men hollers. His voice shoots up into falsetto, then breaks.

Down on the ground, one knee against concrete, your daughter is crouched, just now looking through a fence of legs. The school kids give way and you're rapidly there. She's bloody. You scream. All turn to support you, to assure you she's fine. She's cradling a cat who squirms in her arms. It tries hard to lick loose a makeshift bandage. So. All this time you've been frantic, they've been gathering twigs for a splint, cutting gauze from a Kotex, winding sticky, black electrical tape around a tabby's paw.

"Can't you see it's a school zone, chump?"

"This ain't the Atlanta 500." A punch is thrown.

"Take it easy," one cop says in no hurry.

"Calm down. Calm down."

You're calm. That is, you're on your feet, though your ankle throbs and you're ready to collapse. You rearrange your face and try to act like a grownup while your daughter, talking in gasps, tells it all hurriedly. Hit and run, poor kitty cat, brothers stop mean man at the light, force car back in reverse, Block Parent calls Humane Society, they don't do vet service, mean man fusses at her for diving into street to save a damn cat, children gather and fuss back, angry brothers jump mean man, friends help mend cat, cops finally come, and how come Mommy you forgot to meet me for swim class? The Block Parent jingles keys in her pocket to get your attention, then raises eyebrows at you. Some mother, she mutters, leaving your child alone on the corner waiting to go to the pool. This is Atlanta, woman, where've you been? She talks out of the side of her mouth, her eyebrows doing most of the scolding. You drop your head. The cops write a ticket. One of the Bloods takes the cat. Another reaches round the cops to swipe at the driver.

It catches you in the back of the knees. November 16, Monday, first swim session, free too, parent's signature required, and your child's a fish. The Block Parent is right, where've you been? Your daughter hands you her book bag and helps you up the steps to the pool, teasing you for being so absent-minded, cracking on the table runner wrapped round your head, laughing at your overall tacky appearance. Has a grand time laughing at you. You let her, you help her. She's 11 years old and entitled. You are a mess.

For longer than you want to think about, stumbling to the desk to register, it's been hard to laugh freely. Though at your house there've been no nightmares, bed-wetting, fits of rage, uncontrollable tears, anxiety attacks, onset of asthma, depression, withdrawal, or any other symptoms mental health workers keep discussing in the media, there's been a definite decrease in the kind of clowning around that used to rock your household. At community meetings, child psychologists have been cautioning parents, teachers, youngsters alike to stay alert to changes in behavior, for the Atlanta holocaust has taken its toll. You've observed and you've marvelled at the resiliency of the young, their ability to maintain a firm but not clenched-fist grip on their senses. Your nephew one night let his macho mask slip to show you a scared little boy trying hard to be brave for the sake of his parents. Life is hard enough for grownups, he said, with all of their problems without worrying them further with a scarified him. In relating his feelings to your daughter, however, he camouflaged it all in the language of brag.

You jog around the pool as your daughter comes from the locker area, stuffing braids under her swim cap. It's time, you're telling yourself, to resume body work and get back to. . . . You can't finish the thought. You're wasted. You drop yourself down on the bench, greet parents, joke with older kids you know come to watch younger brothers and sisters splash about in the pool. You rummage around in your daughter's book satchel and smile. Once again she's mistaken your journal for her math notebook, same color. You wonder how she fared in fifth period with your Missing and Murdered notes.

You began the journal in September, 1979, when a few folks began asking, "What is going on?" The entries got lengthy in June, 1980, when the outraged parents, having organized STOP, camped out at media and law enforcement offices demanding a special investigation of the "epidemic of child murders" that had gone on unchecked for a year. The journal ends in fall, 1980, after the explosion at the Gate City-Bowen Homes Day Nursery on October 13 that brought the case to national attention and provoked widespread speculation about the killers and their motives:

white cops taking license in black neighborhoods again?

the Klan and other Nazi thugs on the rampage again?

diabolical scientists experimenting on Third World people again?

white avengers of Dewey Baugus, a white child beaten to death in spring, 1979, by, allegedly, black youths (D.A. Slaton's theory at the time) going berserk?

demonic cultists using human sacrifices?

a child prodigy grown mediocre adult killing her/his childhood over and over?

a craved Vietnam vet who couldn't make the transition?

UFO aliens doing exploratory surgery?

parents of a raped girl running amok with "justice?"

porno film makers producing "snuff flicks" for export?

a band of child molesters covering their tracks?

new drug forces wiping out the young, unwitting couriers of the old forces in a bid for territorial rights?

unreconstructed peckerwoods trying to topple the black city administration?

plantation kidnappers of slave labor issuing the ultimate pink slip?

Journal No. 2 you selected carefully from an arts supply store, a perfect-bound sketch book totally unlike your daughter's spiral notebook. The focus shifts from What's Going On? to Why Is So Little Being Done? The parents charged that the authorities dragged their feet and kept the lid on the case tight to soothe the nerves of the Chamber of Commerce and other business interests in Atlanta, the nation's third busiest convention city. Others, who shouted "ineptitude" one day, later argued collusion, coverup, conspiracy — particularly after a look-alike of a sketched suspect observed at the site of a dumping, one of the few white suspects given media play, was found dead in a car with rope in the trunk signifying "fibers" and "strangulation" and was promptly labeled a suicide; particularly after authorities refused to air a phone call that accurately predicted the site of the next dumping — surely someone could have identified the caller; particularly after medical examiners charged that investigators had tampered with evidence; particularly after citizen search team members accused the investigators with failure to follow through on leads they unearthed; particularly after the hasty discrediting of the overwhelming body of evidence pointing to the cult. No investigation team, folks argued, augmented by numbers of flown-in supercops, assisted by so much souped-up technology and state and federal expertise, could be that incompetent except by design.

Chet Detlinger, ex-APD cop and current police academy instructor, offered the Rumpelstiltskin Complex as an explanation of the morass. Like the medieval dwarf with alchemist leanings who would transmute flax into gold, we all are under the spell of Hollywood/TV scenarists and academic criminologists who spin theories miles away from the beat, who convince us that police work is scientific, sophisticated, technological. The Los Angeles Police Department [LAPD], for example, has impressive paraphernalia — helicopters, sleek weaponry, computers, well-equipped crime labs, James Bond-type gadgetry. Yearly they produce a great deal of flax. The APD, in comparison, to paraphrase Detlinger, is a bunch of double amputees fiddling about with junk from the pre-wheel era, producing yearly very little flax. But neither, the point is, produces any gold.

In the latter half of Journal No. 2, you try to capture the Dodge City face-offs as gleaned from the media versions, as reported by the players, as interpreted on the block: jurisdictional disputes between officers and agencies of the various counties, between city and state and federal bureaus; bad-mouthing between the police and the community, between the Task Force, private investigators and community workers, between STOP and organizations fund raising, between the parents and city officials, between the media and the community. The cast of characters growing daily — psychics, suspects, bat squads, witnesses, hypnotists, dog trainers, forensic experts, cult specialists, supersleuths, visiting celebrities. Funds being raised for reward, for tracking-dogs, for burials, for computers, for armed helicopters. A lot of flax is woven. But no one produces any gold.

By the time you cracked the spine on Journal No. 3, mail, money, camera crews, and letters of support and solidarity were pouring into Atlanta from all over the country, from all over the world. Reports came in too of escalated attacks on blacks that prompted you to shift emphasis from Whodunnit to What Does It Mean In Light Of What Is Happening To Us? The missing and murdered children of Atlanta, the butchered cabbies of Buffalo, their hearts hacked out. The slashed of New York, the stomped of Boston, the children of Trenton, disappeared. Black joggers felled by snipers in Utah, Oklahoma, Cincinnati, Indianapolis. White hunters in Springfield with no deer in sight shoot black men instead. In Chattanooga, Klansmen pick off five black women and flee. Michael Donald lynched in Mobile, a decomposed body found in Tuscaloosa, in South Carolina a five-year-old black boy on trial for his life, in San Francisco a white woman explains that she lured a nine-year-old black boy to her car and choked him, then stabbed him and cannibalized him too because it was her duty as a white mother. Armed training camps of Klan-type groups reported all over the country. The Algiers-Fisher projects under siege in New Orleans after cops break into the wrong apartment to execute drug dealers, the community charges they double-crossed them. Brutal cops being acquitted with regularity by all-white juries; civilian review boards systematically dismantled. Voting Rights Act under attack, the Freedom of Information Act being eroded, an executive order to give CIA license for domestic spying signed, community-based action groups and their sponsors harassed by the IRS and FBI. The Pickens County 2, the Chattanooga 5, the Greensboro 5, the Tchula 7, the Wrightsville 2. And while diplomats of the Klan visit fascists in the Pyrenees, break bread with forces in Italy, France, West Germany, Britain, rallying the psychopaths to annex the whole globe — and while fightback troops taking a courageous stand against imperialism/racism/etc. are being burned out — black students on Atlanta campuses debate whether to invite the Grand Dragon to speak for an $800 fee. The Reverend Abernathy breaks the deadlock by offering his church as venue and an ex-SNCC veteran sets up the lights to film the event. Madness.

Your new journal sits open at home ready for notes on the Williams trial and the trials of the Techwood Bat Squad, definitely not the final chapters, says that segment of the community that will not go to sleep. "Scapegoat," says one grandmother, regarding Wayne Williams, "an excuse to close down the Task Force and scram." One father maintains, "Whatever the verdict, it won't close the books for me. I'm not that stupid." Camille Bell of STOP will work on the defense team. An odd mix of citizens are making common cause to raise funds for the Williams defense. "If we allow them to get away with this legal lynching," says community workers, "they'll clamp the lid down so tight, there'll never be a resolution." Since June all official investigative energies have converged on Wayne Williams. The authorities and the media encourage the spread of the sleeping-sickness epidemic. It is quiet in Atlanta. Just an exhale, you're hoping, folks taking time out for a recharge is all. Too many questions are still unanswered. Too many stories not yet told. Too many cases never got to the Task Force. And there's too huge a discrepancy between the official version of things and the community's.

Official: Between summer, 1979, and summer, 1981, 29 cases loosely linked by race, geography and/or fibers include: one still missing boy, two kidnapped and murdered girls, six abducted and murdered young men, 20 kidnapped and murdered boys. Abductions ceased in June, 1981, with the arrest of Wayne Williams.

Community: Between spring, 1979, and fall, 1981, more than double the official count of cases are linked by race, class, geography and five apparent motive-method patterns: one missing boy, eight girls kidnapped and murdered, more than eight young men abducted and murdered, at least 24 boys between nine and 18 kidnapped and murdered, and at least 35 women abducted and murdered. Four of the boys, one of the girls and five of the women were killed while Wayne Williams was under arrest.

The grapevine report is that both Police Chief Napper and No-Rap Brown, as folks have tagged the Commissioner of Public Safety, have been responsive to out-of-town job offers. What then will happen to the Task Force, the investigation, if they pull out? And where are our armies and navies, now that war has once again been declared? Where are our soldiers on 24-hour, red alert combat duty — mobilizing, organizing, building coalitions with other downpressed communities, investigating, documenting, analyzing, defending, remembering, daring to see and understand?

Last summer, the Senate subcommittee on terrorism and security held its hearings to which we, who experience every brand of terror daily and experience no security of any kind at any time, were cordially not invited to give testimony about the war. The war waged on the highways and local streets of upper New York State as the FBI & Co. unleashed a reign of terror on the populace in an all-out attack on the BLA, the RNA, the Weather Underground and other "outlaws" who raise critical questions about the state's right to declare war against the people physically, politically, economically, socially, culturally. Legal lawlessness intensifying as the hunt for Assata Shakur and any other disturbers of the bogus peace, the insane order, moves south along the Eastern seaboard. A rural district in Mississippi is terrorized by helicopters thick in formation, crowding the sky, roads jammed for miles with tanks, patrol cars, vans of overkill-outfitted troops: an army of occupation come to arrest an RNA officer not on the scene. They shackle instead another RNA officer, the wife, Cynthia Boston, on evidence that would make an earnest law student drop out of school. They handcuff her knee-high infants called "desperadoes" by those who wage war.

FBI Director William Webster moves center stage to croon his theme song "Not Racially Motivated," the lyric composed when Vernon Jordan got hit, the song making the charts during the Atlanta holocaust — "Not Racially Motivated" — definitely no connection between acts of violence in one place and acts of violence in another, goes the refrain. Black leaders not born of the Fires of struggle are trotted out downstage left to doo-wop the cool-out chorus, becool bequiet, eight to the bar. From the wings comes a punk rock group who call themselves white radical feminists, from the orchestra pit rise instrumentalists in tails who claim to be radical black sociologists; their routine the same, designed to inform us of the increasing insignificance of race in the current scheme of things. They go on the road with the Race Has Nothing To Do With It Show. We've heard it before from the apologists of the Tuskeegee Study when, from 1932 to 1972, 600 guinea pigs, all of whom happened to be black men, uh huh, were studied by government-funded scientists, but not treated for syphilis that ravaged them and their families. The doctors took notes while their subject chancred, festered, bled, passed on the disease, went blind, went nuts, then died. Six hundred black men chosen by government-funded scientists.

"It could just as well be a preference for blacks as a prejudice against them," said FBI Webster, speaking of the Atlanta children snatched, murdered, dumped. You're thinking about that mother in that cold basement room, the sheet being pulled back, the tag on the toe. You roll your daughter's notebook into a bat, eyes closed, telling yourself it's the chlorine fumes from the pool getting to you.

A cheer goes up from the back benches. A youngster is making his debut in the nine-foot depths, diving from the rim of the pool, coached by the lifeguard who now makes the most of this moment — sucks in, flexes his biceps, eight separate segments of abdominal muscles gleam in bas relief. You're appreciative. From the other end of the pool, the kiddies splash chasing a big red ball. You tune in again to the talk around you, grateful it's not about murder and not about normalcy. Your daughter calls you from the pool. You stash the notebook. You rise and look. She's doing an arms-spread, face-down float. As if practicing being dead. Should you applaud?

Tags

Toni Cade Bambara

Toni Cade Bambara is a writer and activist, whose most recent book is The Salt Eaters (New York, Random House, and London, The Women's Press, 1982). She was co-editor of Southern Exposure's special issue, "Southern Black Utterances Today" (1975). (1983)