This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 5, "The Meaning of the McSurely Case: A Seventeen Year Inquisition." Find more from that issue here.

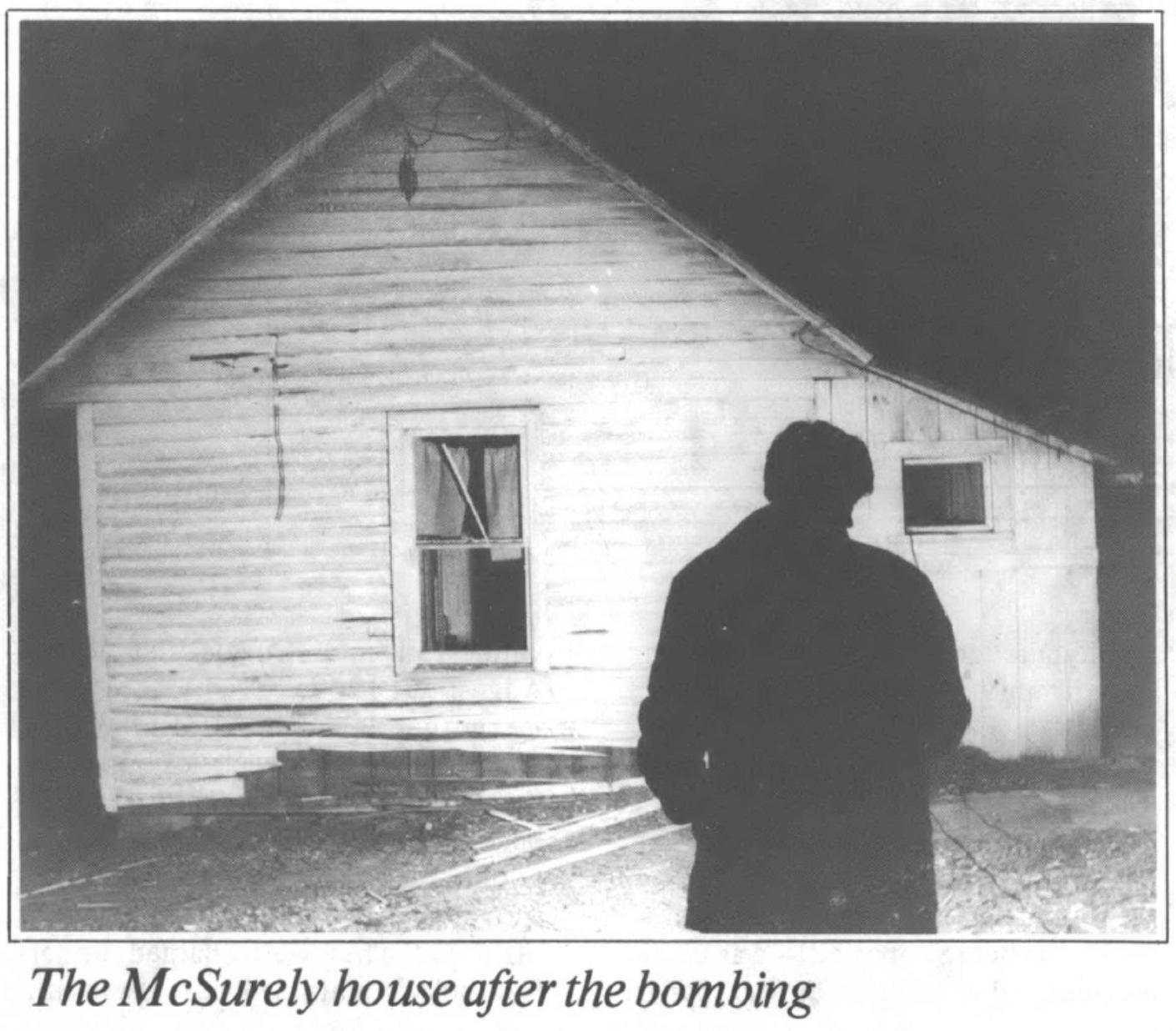

The blast came at about one in the morning. Dynamite blew the boards off the side of the mountain shack just below the bedroom window. Inside, Alan and Margaret McSurely were thrown from their bed. They found themselves on the floor, on their knees, gasping for breath. Margaret remembers the odor of sulphur. Alan remembers the dust.

"I was having trouble getting my breath," Alan said. "My lungs hurt. I couldn't tell whether it was concussion or whether it was because the air was so full of dust."

While Alan scrambled into his clothes in the darkness, Margaret rushed to the crib of their year-old son, Victor. There was no sound now except for the hollow echo of the explosion ringing in their ears.

"Then Victor stood up in his crib and started screaming," Margaret recalls. "When I picked him up I felt broken glass all over him. He was covered with dirt and debris.

"We were lucky it was so cold. It was about seven degrees outside, and not much warmer in that old house. We were sleeping under heavy blankets and Victor was in an infant sleeping bag. I think that was what saved us."

Alan thought a gas line had burst, causing the explosion. He started outside to check. Margaret stopped him.

"I told him it wasn't the gas line," Margaret said. "We'd been bombed. I just knew it. Al couldn't believe it. He couldn't believe anybody would do anything like that to him."

Moving to an adjoining room, Alan looked out the windows into the darkness to see if there was anyone nearby Margaret quieted Victor, then after a moment they heard a car start and drive away.

"I knew she was right then," Alan said. "It couldn't have been anything else. Somebody had been out there, maybe just waiting to see if we came out."

After a period of time — neither can estimate how long — they began gathering their wits and planning their next move. If the bombers didn't hit them again right away they might have a chance to escape.

They hurried across the road to a neighbor's house and called the state police to report the bombing. After the officer arrived and surveyed the damage, Alan and Margaret hastily piled a few of their belongings into their van. It was about three o'clock in the morning.

"It was time to get out of there," Margaret said.

They headed to Lexington, about a hundred miles away, where they had friends.

A complaint was filed with the U.S. Attorney's office in Kentucky asking the FBI to investigate. The McSurelys then headed east, to Arlington, Virginia, Alan's boyhood home.

Fifteen years later, seated on the couch in her living room in Brookmont, Maryland, Margaret talks about the episode with deceptive calm. Her speech is slow and measured, interspersed with frequent pauses. There is a dream-like quality in her recounting of events that cold December night in the Kentucky mountains. She emits an occasional short burst of nervous laughter as she tells the story, as if to ease the tension.

When Alan talks about the bombing he is a bit more intense. "The rotten bastards might have killed us," he said. "They sure intended to. You don't throw a bundle of dynamite at somebody's bedroom window unless you plan to blow them away."

When Margaret and Alan McSurely arrived in Pike County in the spring of 1967 as anti-poverty workers they knew little about the nature of their surroundings. They knew that it was one of the most severely poverty-stricken areas of the country, but that was about all. Not until they had been there a while did they learn that in the face of all that poverty, Pike County was the heart of the nation's leading coal producing region, providing enormous profits for mine owners and operators. The county seat, Pikeville, a town of about 5,000, boasted of having more than 60 millionaires among its residents. At the same time, nearly half of the families living in the county were officially designated as poor, with many others just above the poverty line. These were the coal miners and farmers, descendants of generations of mountain families who had known poverty and deprivation as intimately as they knew the level of credit at the company store.

Within a month after their arrival, Alan ran afoul of some of the officials in the bureaucratic structure of the anti-poverty program. As training director for the Appalachian Volunteer [AV] program, an agency under the federal Office of Economic Opportunity [OEO], Alan had considerable influence over the methods and programs instituted on behalf of the local residents. Prior to his arrival he had been working on an organizational plan entitled "A New Political Union," which he hoped would be adopted on the national level as the framework for an independent political movement outside the two major parties. Essentially, the plan called for the establishment of regional councils for governmental rule, to replace the traditional city, county, and state administrative units.

"My idea," Alan recounts, "was that if we divided the United States into, say, 10 geographic regions governed by regional councils the people would have a much greater voice in government decision-making. But of course that meant doing away with the existing power blocs, and it was looked upon as an openly socialistic technique."

On one social occasion at the McSurelys' house, Alan showed a draft of his plan to one of the other members of the anti-poverty workforce. "I probably wouldn't have shown it to him, but living the way we were, pretty much isolated from any sort of intellectual stimulation, you feel like you have to latch onto anybody you can to have somebody to talk to about things you're thinking about. But he got all excited about it, and first thing I knew he'd made several copies and passed them around to other people. A consultant to the OEO who was a friend of Sargent Shriver (head of the OEO at the time) got wind of it and it blew his mind. He called my boss, the director of the AV program, and told him what he thought I was up to, and if he didn't fire me the AVs wouldn't get any more federal money.

"The firing by the AVs probably radicalized me more than I was before," Alan recalls. "We'd been pretty effective in getting people molded together into an active group, but in the federal programs you had to be careful not to antagonize the local power structure. I guess I had violated that rule. But the people I was working with — the locals — seemed to like what I was doing and we were having fun getting things done."

Perhaps they were, but the local political leaders were not enjoying the efforts at all. To them, it was nothing but trouble.

On the evening of August 11, 1967, one year before their house was bombed, Alan and Margaret were at home in the little rented mountain shack on Harold's Branch when, at about 8 p.m., they heard a commotion outside. Their dog began barking, and when Alan got up from his reading table to determine the cause of the disturbance he was surprised to see 15 county officials and sheriff's deputies descending on their house from the twisting dirt road that ran nearby. Leading them was Thomas Ratliff, the commonwealth attorney for Pike County.

"I thought they were looking for an escaped convict or something," Alan recalls. "I started to open the door but then it just came crashing in on us. They forced their way in. I looked around and they were coming through the back door too. They started trashing all our stuff, dumping all our papers and books and things, clothes too, all over the floor."

Meanwhile, as Alan tried to get the officers to tell him what the trouble was, Margaret slipped into the bathroom, taking the telephone with her.

The telephone — as Margaret sees it — is the one crucial piece of equipment for any civil rights workers, as the link from unfriendly territory to the outside world.

"It was instinctive to pick it up," she said. "I just naturally headed for the bathroom. It was the only place where I might be safe."

As it turned out, she was in the bathroom for about an hour during the time the officers were boxing up their papers and hauling them out to a waiting truck. She called people they knew, anyone who might be able to help.

"I just wanted people to know what was going on," she said, "so if anything happened to us they'd know." One of the people she called was a local lawyer who had been friendly toward them.

"I think I knew what was happening," Margaret said. "I guess I had expected something like that. Al had been going around the county a lot just before that, talking to people at night in little groups, visiting people way back up in the hollows at their houses, getting home late, and I had been getting worried about it. Being by myself a lot at night, and being about five months pregnant, I was getting a lot more security conscious. We'd had threats before, and they'd been getting meaner. I was afraid they might kill Al some night out on one of the mountain roads. Nobody would've ever known who did it or how it happened.

"There were plenty of people there who didn't like us," she concedes. "And not just the wealthy and powerful. Some of the poor people accused us of being communists too. I asked one man what he thought a communist was and he said it was anyone who didn't agree with his way of life.

"Some of them said we didn't believe in God, we didn't believe in the Bible. But when they raided us and took all our papers and books with them, about all they left was the Bible we had. I guess they didn't figure they needed that to prove we were bad people."

What they did get was a collection of personal papers and documents, including books and pamphlets, among which were writings by Lenin, Marx, Che Guevara, and Fidel Castro. The collection was later referred to by County Prosecutor Ratliff as "a communist library out of this world."

"It was a matter of opinion," Alan relates. "I'm a socialist. I've never hidden that. We had all sorts of things. We'd been working in civil rights organizations and we used anything we could to build collective units."

The McSurelys were charged with attempting to overthrow the government and jailed in Pikeville. The local lawyer whom Margaret had called warned jail officials about allowing harm to come to them.

"I was really scared," Alan says. "Guys had been pushing me around, telling me to hold my head up so they could see what I'd look like when I was hanged. I didn't know what might happen. It looked like a lynch party to me."

Alan was locked up in a dormitory-type room with about 15 other prisoners. He remembers that they all woke up when he was brought in and began asking questions about him. A jailer told them he was a communist.

"I didn't know what they might do to me," he says. "So I just lay down on an empty bunk and tried to go to sleep, figuring that if they killed me I'd be dead when I woke up. Crazy, huh?"

He fell asleep, and awoke the next morning unharmed.

Meanwhile, Margaret had been put in a cell with two other female prisoners. "When I told them I was charged with attempting to overthrow the government they both said that's what should be done," Margaret said.

The McSurelys languished in jail for about a week while their lawyer tried to arrange for their release on bail.

Subsequently, a federal panel of three judges was convened in Lexington to review the charge. The decision was blunt and to the point. The sedition law was declared unconstitutional and the charge was ordered dropped. In part, the panel's decision read: ". . . it unduly prohibits freedom of speech, freedom of the press and the right of assembly. . . ." Further, it stated: "It is difficult to believe that capable lawyers could seriously contend that this statute is constitutional."

The seizure of the McSurelys' personal papers and documents became the focal point of a series of legal maneuvers over the next year. Eventually, all the material was ordered returned. But not before over 200 of the McSurelys' documents had been copied and delivered to the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, headed by Senator John McClellan of Arkansas, which had been engaged in a probe of the urban disorders of the 1960s.

"We [together with their lawyers] decided that McClellan was trying to use the race-riot thing as a camouflage to get at our personal stuff to use for his own ends," Margaret said.

McClellan subpoenaed the McSurelys to appear before his subcommittee and to produce all the previously returned documents. The McSurelys refused to cooperate, contending that their Fourth Amendment rights had been violated in the initial seizure — a point of argument upheld by the courts when the material had been ordered returned.

This point, however, did not prevent McClellan from citing the McSurelys for contempt of Congress, and at the same time branding them as part of a worldwide communist conspiracy. When asked for a response, Alan McSurely replied that yes, they were engaged in a conspiracy — to unite the unemployed, the working poor, and blacks into a coalition that could demand, and get, their rights as citizens of the United States.

The McSurelys were tried and convicted on the contempt charge and sentenced to prison — Alan for a year and Margaret for three months.

In a statement to U.S. District Judge John Lewis Smith, Jr., Margaret said, in part: "Judge Smith, I hope you don't mind if I talk plain to you. You knew when we were arrested in Kentucky in 1967 and our personal papers apprehended there was a fierce struggle going on between coal operators and the people. . . . You knew our home was raided and our papers were seized under an unconstitutional state law. These papers were given to McClellan, and yet our rights were not protected in your courtroom. You knew that McClellan lied to the United States Senate when he said the subpoenas were based on outside information about our involvement in the national disorders . . . and again our rights were not protected in your courtroom. You agreed to a set of rules . . . designed to thoroughly confuse the jury and to violate due process, and still our rights were not protected. You graduated at the top of your class at Georgetown Law School. You're a smart and experienced judge . . . you have an understanding of the Constitution . . . you know the law and the facts in this case. It all boils down to whose interests you serve. . . . Each time you ruled against fair play, you taught more than a hundred of our speeches could. So when they speak of contempt or disrespect for the judicial process, remember what you taught them."

Another protracted legal battle then ensued. For two and a half years the McSurelys lived with the uncertainty of whether they would be going to prison. They made arrangements for the care of their son Victor — now four years old — in the event that their appeal failed. On one weekend they drove from Washington to the federal women's prison at Alderson, West Virginia, where they thought Margaret would be incarcerated if they lost the case. When she saw the place, Margaret recalls, "I was terrified."

In December, 1972, the U.S. Court of Appeals handed down its decision. The contempt conviction was reversed. The court ruled that the search warrant used in the raid on the McSurelys' house was invalid and that it violated the Fourth Amendment, and that the Senate subpoenas were based on illegally seized evidence.

The McSurelys were both gratified and embittered by the outcome. Margaret said at the time, "I couldn't believe it at first. Finally we were vindicated. And, of course, I was real glad we weren't going to prison. But then I realized that they could never pay us back for all the time and energy we had spent. . . . What could make up for our pain and frustration and fear and helplessness? It was true that the law had ultimately worked for us, and we could believe in the Bill of Rights again. But we had paid a terrible price."

A civil suit for damages was the next step in the long-running judicial saga. Defendants were McClellan, two of his subcommittee aides, and Thomas Ratliff, the Pike County prosecuting attorney.

Over the next 10 years the McSurelys and their lawyers were in and out of court as they fought to overcome the defendants' delaying tactics, principally those of the U.S. Justice Department which was representing McClellan and his aides as officers of the government. Paramount in the defendants' argument was that a member of Congress could not be sued for damages for activities conducted in the normal pursuit of his governmental duties. When the Supreme Court ruled that this protection did not provide absolute immunity, the suit proceeded to trial.

It was November of 1982. For the McSurelys, the end was in sight. All the points of law had been argued. Now, all they had to do was present the facts of the case to a jury, and let its members determine how much money the defendants should pay for their misdeeds.

Testimony stretched out over a period of six weeks. The judge in the case, William B. Bryant of the U.S. District Court in Washington, permitted both sides wide latitude in the presentation of their case. The McSurelys were finally able to tell in detail about the events that had dominated their lives over the past 15 years.

One bit of evidence, however, was not allowed — the account of the bombing at the McSurelys' house. The judge ruled that such testimony would be too inflammatory and therefore prejudicial.

On January 7, 1983, the six-person jury ruled for the McSurelys, awarding them $1.6 million in damages. A breakdown of the damages included $218,000 charged against the estate of the late Senator McClellan; $1.2 million against Thomas Ratliff, the Pike County prosecutor and coal company owner whose personal wealth was estimated at $3.9 million; and lesser amounts against the two Senate aides who worked for McClellan.

The decision of the jury that Ratliff — as the principal wrong-doer in the case — owes the McSurelys $1.2 million, does not lighten Alan's feeling of enmity toward him.

"He was a public official," Alan said. "He had higher political ambitions and he was using us to promote his career. He was running for lieutenant governor of Kentucky at the time of the raid on our house and he thought he could get some political mileage out of it. He went around telling people how bad we were, that we were communists and that we had all kinds of evil plans in the works. He even suggested that we were planning to bring Russian tanks into the streets of Pikeville to overthrow the government. He hurt us. But he didn't win the election.

"Then a year later we were bombed. There wasn't much of an investigation, as far as I could tell. Ratliff even suggested that maybe we had bombed ourselves to get sympathy. I hate the bastard."

Following the reversal of their contempt-of-Congress conviction, Alan was quoted as saying: "It's not justice that we are finally proved right. . . . Justice would be that we were never arrested, or, if mistakes do happen, justice would be that the mistake was corrected fairly and quickly." He later added, "They made a real mistake in persecuting me. Before all this I was just a liberal reformer. Now I'm a real revolutionary."

Does he see the outcome of their case as encouragement for latter-day civil rights proponents?

"There are some big 'ifs' connected with that," he said. "If it hadn't been for the Freedom of Information Act, we wouldn't have been able to get the documents we needed to build our case. If we hadn't had the best constitutional lawyers in the country working for us, for free, we wouldn't have had a chance. And if we hadn't drawn a judge who was willing to sit back and let both sides have their say — something we haven't always had over the past 15 years — we might not have won it. Those are some pretty big 'ifs.'"

Do they feel vindicated by the district court jury's decision? Do they feel compensated by the $1.6 million award for damages? "Vindicated? Yes," says Margaret. "Compensated? No. Money helps though.

"But the important thing is we made a point," she adds. "They [police and governmental officials] will think twice before doing something like this to somebody else. They'll know they can't step all over you just because they don't like you, or because they're afraid of you or of what you're trying to do."

"What we did is worth it because of our kids," was Alan's response. (He and Margaret had two children each by former marriages.) "The official public indictment was that we were trying to violently overthrow the government. Then, when we refused to turn over our personal papers to the Senate, it looked like we had something to hide. To have it [the case] heard in a calm setting, like a court of law, it's easier for the children to understand what we were trying to do.

"They're all old enough to know now," he said. "We talk about it. I think they understand."

Tags

Charles Young

Charles Young is a free-lance writer based in Greensboro, North Carolina, and Richmond, Virginia. (1983)