This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 5, "The Meaning of the McSurely Case: A Seventeen Year Inquisition." Find more from that issue here.

A federal court jury in Washington, D.C., in January, 1983, awarded $1.6 million in damages to two private citizens, Al and Margaret McSurely, who claimed their constitutional rights had been violated 15 years previously in Pike County, Kentucky. The damages were assessed against the estate of the late Senator John McClellan, two of his aides, and Thomas Ratliff, millionaire coal operator who was Pike County prosecutor in 1967.

For anyone ever abused by public officials, the verdict said that two Davids had wounded Goliath, and that the U.S. Bill of Rights could prevail. For Al and Margaret, the jury decison — although not the end, because the verdict is being appealed — was an important milestone and at least partial vindication in a struggle that started August 11, 1967.

On that day at sunset, Ratliff and 15 armed sheriff's deputies burst into their mountain cabin, ransacked their belongings, took away a truckload of books, records, and personal correspondence, and hauled both McSurelys off to jail. They were charged, under Kentucky's state sedition law, with conspiring to overthrow the governments of Pike County and Kentucky. Along the 15-year road to the Washington courtroom, Al and Margaret McSurely saw their belongings confiscated by McClellan, resisted subpoenas of his Senate committee, and were convicted of contempt of Congress. Al was sentenced to a year in prison and Margaret to three months.

Those sentences were set aside in 1972, but by that time the McSurelys had long since left Pike County — at 4 a.m. December 13, 1968, after dynamite thrown from a passing car exploded under their bedroom window, raining shattered glass into the crib of their year-old son, Victor, and narrowly missing killing the three of them. No one has ever been prosecuted for that crime.

The McSurely case is a testament to the legal skill of lawyers at the Center for Constitutional Rights in New York, who represented them without fee through myriad criminal and civil actions — and to the tenacity of Al and Margaret who were determined to prove that public officials cannot trample on rights of citizens with impunity.

They had a lot going for them. They were young (both 31 in 1967), healthy, physically attractive, intelligent, and highly articulate. Through that era's social-justice movements, they had friends throughout the country and the support of the Southern Conference Educational Fund [SCEF], on whose staff they and I worked and whose public-information machinery had been finely tuned through many battles against repression. The public heard about the case, and the McSurelys struggled not only in courts of law but in the court of public opinion. Al said in 1973:

"If we don't fight back in every arena open to us — the courts, the marble halls of the Senate, the press, the streets, the ballot box — we are letting ourselves down and all our brothers and sisters in the human family."

The real story of the McSurely case goes beyond their personal struggle. Its deeper significance lies in the slender ray of light it sheds on a period that has not yet been properly recorded by historians, the late 1960s and early '70s.

When the McSurelys went to the coal-producing country of Pike County in early 1967, they became part of a growing movement of poor white people in Appalachia that had begun in the early '60s. It was one of the many movements of that decade, inspired by the Civil Rights Movement, that shook the country to its roots and terrified people in power.

The McSurelys themselves as young white people were part of a small army whose lives had been turned around by the black freedom movement. By the mid-'60s, they like many others were on fire to help poor and working white people build a movement that could develop an alliance with the burgeoning black movement to turn the nation around.

When they came under attack, the McSurelys were just two among many victims of intense repression that descended on the nation's movement for social justice. That period of repression is little understood. In a way, it was worse than the McCarthyite repression of the 1950s — and I lived through both. In the '50s, many people suffered, went to jail, or lost jobs and saw careers ruined. But Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were the only ones killed by the government for their political beliefs. By contrast, in the late '60s, not only was Martin Luther King, Jr., murdered in a case that strongly suggests government collusion and has yet to be solved — but many younger skilled organizers working in the black liberation struggle were murdered all over the country; black organizers in scores of communities were shot at with impunity by police, and activists were sent to jail with long sentences on a variety of criminal charges, most of which were later proved false. The repression of the late '60s may not be as well known as that of earlier periods because most of the victims were black and so much history is still written from a white viewpoint.

I was traveling the South then as a staff member of SCEF, which was an interracial organization dedicated to civil rights and social justice. I remember well that one could hardly visit any community without finding that its key black organizers were either in jail, on their way, or just out after much struggle. I was also helping to edit SCEF's publication, The Southern Patriot, a newspaper covering events in people's movements. Recently, I went through those files to refresh my recollections of that period. Month after month, page after page, between 1967 and 1973, headlines and articles told the grim story.

For example: Armed police attack black student protesters in Houston, five students jailed on spurious murder charges; press and police attack a black liberation school in Nashville that was later forced to close, leaders of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee [SNCC] in that city jailed on conspiracy charges; black organizers in Gainesville, Florida, held all summer under high bonds; six black organizers in Louisville jailed for conspiracy to bomb oil refineries — charges dropped three years later because there was no evidence; police shoot student protesters in Orangeburg, South Carolina, killing three people and wounding 50, the police later acquitted and SNCC leader Cleve Sellers going to prison.

Or: Armed force against high school and college students in Greensboro, North Carolina, with one student killed and 35 wounded; police invade Knoxville College campus, students held nine weeks without bond, one finally sentenced to 10 years; black organizers jailed on long terms in St. Petersburg; organizers of Black and Proud School in Jackson, Mississippi, under attack by local police and the FBI; SNCC organizer in Texas sentenced to 30 years for selling one marijuana cigarette; police attacks on Jackson State College in Mississippi — one student killed in 1967, two more in 1970; raids on Black Panther offices in New Orleans and North Carolina communities.

Or: Blacks filing for office in Mississippi suddenly called by draft boards; leaders of welfare-rights group in Jacksonville, Florida, charged with extortion after attending a ministers' meeting to ask for money; armed police and FBI attack on house of Republic of New Africa leaders in Jackson, Mississippi, a policeman killed in self-defense, 11 RNA leaders sent to jail in 1971; 20 sheriff's deputies breaking down a door in a working-class Birmingham suburb, shooting, wounding, and arresting two leaders of Alabama Black Liberation Front, because police "believed they were planning" violence to prevent eviction of a poor woman; Black Muslims in Baton Rouge charged with inciting to riot after police attacked a street meeting with guns and clubs.

This is just a sampling. Ghettos were erupting across the country, and in 1968 the President's Commission on Civil Disorders (the Kerner Commission) issued a report citing the cause as social and economic conditions and saying that "almost invariably the incident that ignites disorder arises from police action." But local officials, with federal support, acted from a different premise. They saw every black gathering as a potential revolution and used this as an excuse to jail organizers. The most usual targets in the South were SNCC members, and those with long records of community activism.

The sharpest attack was on two SNCC leaders — Stokely Carmichael, whose presence in a community terrified officials, and Rap Brown, whose troubles started when he made a fiery speech in Cambridge, Maryland, and left town — after which a dilapidated school building burned down. Soon thereafter, Brown was under $100,000 bond and the subject of 14 court actions.

In North Carolina, at one point, there were 40 black activists in jail on a variety of criminal charges. One of these cases, the Wilmington 10, sparked a decade-long fight-back that generated a new movement. But most victims of repression languished long in jail, and by the time they emerged local movements they had organized had long ago been destroyed.

The Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and '60s had met violent repression by local officials from its beginning. In the early days there was wide support for activists facing police dogs and fire hoses, and the Movement used the attacks as organizing tools. But the attacks of the late '60s were different. The charges weren't for demonstrating; they were usually criminal charges. Most of these later proved to be frame-ups, but because the nature of the charges confused many previous supporters, victims were often isolated. And the federal government, which had appeared to be on the Movement's side in the early '60s, openly attacked the Movement under the law-and-order Nixon administration, which saw the black movement as a threat to the nation's security.

Although Freedom of Information Act releases and congressional investigations have revealed much information on government repression, the massive attack on the black freedom movement in that period is not widely known. This is partly a reflection of white domination in our mass media. Stories of FBI undercover actions against white activists have been much more highly publicized than those against black groups. Also, there have not been many court suits seeking to uncover more information. SNCC veterans have talked of such a suit, but it has not happened yet. One problem is that when groups are totally destroyed, as SNCC and some other black organizations were, it is difficult to pull together plaintiffs to pursue court action.

Thus, the story of the attack on the Civil Rights Movement has come out only in pieces. Some people think the federal repression started as early as 1964 — after Lyndon Johnson was terrified by the challenge of black Mississippians in the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party at the Democratic National Convention that year. Certainly by 1967, the attack plan was in full operation. The FBI Counter Intelligence Program [Cointelpro] actions against Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., are now well known. We also know that on August 25, 1967, (about the same time the McSurely case was beginning), FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover issued a major Cointelpro directive ordering "experienced and imaginative" special agents to "expose, disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize" what he called "Black nationalist hate-type organizations." Among the targets listed were SNCC, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference [SCLC], CORE, Nation of Islam, Carmichael, Brown, and Elijah Muhammad. And we know that a subsequent Cointelpro memo issued March 4, 1968, expanded the scope of the August directive and added Dr. King as a target. This was the famous memo that ordered FBI agents to "prevent the rise of a Black Messiah." Exactly one month later, Dr. King was murdered.

We also know that a secret memo sent to the FBI by President Johnson's attorney general, Ramsey Clark, September 14, 1967, gave the green light to attacks on SNCC. The FBI, Clark wrote, should use all possible resources to find out whether there was a conspiracy to plan riots and said sources and informants in "Black nationalist organizations like SNCC" should be "developed and expanded." (Clark in more recent years has been on the other side of social struggle, and now represents former Mayor Eddie Carthan of Mississippi in his fight against current repression.)

We who were active in the late '60s did not know about the Cointelpro memos, but we saw what was happening. Some of us were disturbed by the silence of many whites. White protesters were being jailed too — but usually for short periods. With a few exceptions — like the students murdered at Kent State — they were not being shot at, bombed, or imprisoned on criminal charges that carried long sentences. By and large, white radicals weren't doing too badly then.

I commented on this in a 1968 editorial in the Patriot — noting that a federal court had just enjoined a legislative attack on the white-led Highlander Center in Tennessee, at the very moment when Nashville police were conducting mass invasions of homes of black militants in that city. "You preserved freedom," I wrote, "by fighting back at the first signs of attack on it. Today the attack is on militant black leaders. That is where the barricades are, and that is where we who are white had better be, if we value our own freedom."

The McSurelys, who are white, were an exception to the prevailing pattern. They were not in jail long, but they could have been among the martyrs of that period. The dynamite thrown at their house was clearly meant to kill them.

Al thinks they were targets because, although they had actually had time to do very little organizing in Pike County, they represented several things that those in power, both locally and nationally, feared.

"Most of all they feared the black liberation movement," he said recently. "But in addition they feared the possibility of an alliance of blacks with white poor and working people; they feared cadre-type organizations of activists like SNCC had built; and they feared independent political action, outside the two old parties. We were advocating all those things."

The new mountain movement, of which the McSurelys became a part, started in 1963. It began with the activities of unemployed miners who, inspired by the Civil Rights Movement, organized a "roving picket movement" when their health benefits were cut off. About that time, SNCC and other civil rights groups were turning from the symbols of segregation to talk of attacking economic injustice. At a November, 1963, SNCC conference Bayard Rustin noted the need to organize the white unemployed to work with the black movement.

Some young whites took that seriously. The Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) held a conference on Easter weekend, 1964, in Hazard, Kentucky, along with the Committee for Miners, a support group for the roving pickets. Some students stayed in Kentucky all that summer.

That year also, SCEF set up a Southern Mountain Project [SMP] to continue such organizing. Poverty was rampant in Appalachia and unemployment was astronomical while machines did the mining. SCEF had long stood for black-white alliances and felt that now they could be built. In 1965, several groups — including SCLC, SNCC, Highlander Center, the Southern Student Organizing Committee [SSOC], and SCEF — set up the Appalachian Education and Political Action Committee [AEPAC] to coordinate such work. From then on, a succession of white organizers went to the mountains.

Repression was heavy from the beginning. One of the earliest activists was charged with criminal libel after he wrote an article criticizing local officials. In Knoxville, in 1966, a house used as headquarters by AEPAC was burned. That same year, SMP organizers were arrested for vagrancy and disorderly conduct. Soon after SMP staff moved into Sevier County, a rural area near Knoxville, headlines in the local press proclaimed "SCEF and SNCC in Sevier County," and organizers leaving a meeting were arrested with fanfare on traffic charges.

With the constant attacks, no solid organizing was accomplished by the SMP. But ferment was spreading. In 1964, a veteran of SNCC's Mississippi work convinced the Council of the Southern Mountains, a widely respected organization headquartered in Berea, Kentucky, to recruit young people to work in the mountains. The result was the Appalachian Volunteers [AVs], funded by the federal antipoverty program.

The AVs started out by painting old school houses and trying to help the poor get a voice on local poverty program agencies. Within a few years, many had concluded that they must take on the area's power structure, the coal operators. A cross-fertilization of ideas developed between AVs and Volunteers in Service to America [VISTA] and the more radical organizers on SCEF's Mountain Project, most of whom were veterans of the Civil Rights Movement. The McSurelys' arrival in the mountains in April, 1967, cemented these relationships. Al went there as AV training director; Margaret was on the SCEF staff.

Al's employment with the AVs lasted only a month. The AV administrators soon decided he was too radical, and he was fired. Al and Margaret were both very open in their radicalism. Margaret had worked for SNCC in Mississippi; Al had become active through northern Virginia poverty programs. They took their extensive library to the mountains with them, including works by Marx and other revolutionary writers, and displayed it openly. And they talked freely about the need for poor people to organize and take over the reins of government. They also insisted on talking about things like racism and the Vietnam War — issues that the AV hierarchy considered taboo for discussion. All of this made them easy targets, through which the entire growing mountain movement could be attacked.

After he was fired, Al joined Margaret on the SCEF staff and continued his close relationship with many AVs. One of these was Joe Mulloy, who had grown up in a working-class family in Louisville and joined the AVs from college. In summer 1967, Mulloy persuaded the AVs to support mountain people who were standing in front of bulldozers to stop destruction of their land by strip mining. When one such incident caused a mining permit to be cancelled, there was apparently growing fear within the power structure.

Thomas Ratliff, the Pike County prosecutor and coal operator, was running for lieutenant governor on the Republican ticket. On the evening he led the raiders to the McSurely home, he also raided the Mulloy home and jailed him on sedition charges, too. Ratliff announced that his victims had a "communistic library out of this world,'' and were trying to stir up "our poor," and that McSurely planned to organize Chinese-like "Red Guards" in the mountains. Hysteria spread in the community.

Joe's wife Karen, also a mountain activist, was able to raise his $2,000 bond rather quickly. But Al and Margaret stayed in jail a week. No Pike County bondsman would make bond for Al; Margaret refused to leave jail without him, and it took us that long to arrange to post SCEF property in Louisville to cover the $5,000 bond for each of them.

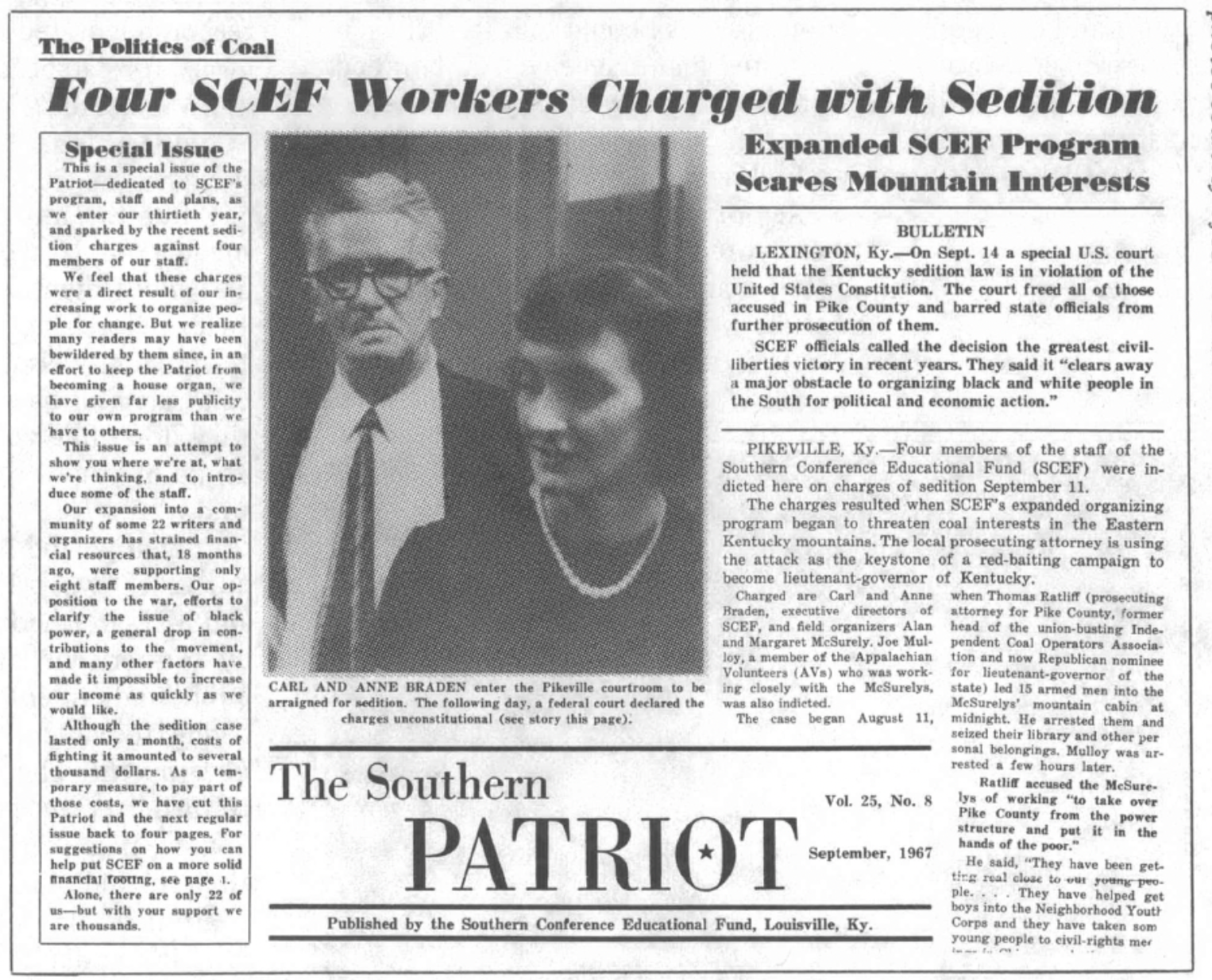

Soon thereafter, my husband Carl and I, as directors of SCEF, were added as defendants under the sedition charges and were also jailed in Pike County when we refused to post $10,000 bond. We had not been working in Pike County, which is over 200 miles from Louisville, where we lived and where the SCEF headquarters were. But we had been jailed under this same sedition law 13 years earlier and had long been labeled as subversives in the state. Thus, our names were useful to Ratliff in his campaign to convince voters that a plot was afoot in Pike County. Also, the Republican candidate for governor that year was already running on a platform that promised to "run the Bradens and SCEF out of Kentucky."

Meantime, SCEF had contacted the Center for Constitutional Rights in New York, and its lawyers had immediately asked a federal court in Kentucky to declare the state sedition law unconstitutional and stop the prosecutions because they were "chilling" free speech. To our amazement, a three-judge federal court did exactly that on September 14, 1967.*

Those opposed to the mountain movement were not giving up. Soon a Kentucky Un-American Activities Committee [KUAC] — we called it Quack — was set up to investigate in Pike County and elsewhere. And it never seemed a coincidence that on the very day after the sedition law was invalidated, Joe Mulloy was sent an induction notice by his Louisville draft board. The board kept a clipping file on his activities, he had lost his occupational deferment, and was applying for conscientious objector status.

Joe resisted the draft on grounds of conscience (the Vietnam War was at its height), and was later sentenced to five years in prison. That conviction was reversed by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1970, but in the meantime Joe was fired by the AVs (at which point he joined the SCEF staff), left the mountains, and spent much of the intervening years either in jail while we raised bond or organizing around his draft case. We had noticed a pattern of controversial organizers, both white and black, being singled out for induction notices. We published a pamphlet on that, focusing on Joe's case and that of another SCEF staff organizer, Walter Collins in Louisiana. We won the case of Mulloy, who is white, but not that of Collins, who is black.

The sedition charges and Joe's draft resistance rocked the Appalachian Volunteers and eventually led to their demise. Joe's stand was especially traumatic. Edith Easterling, a retired miner's wife in Pike County who was on the AV staff and who loved Joe like a son, said to him: "Joe, how can you do this to us? We're against the war too, but in the mountains, when you're called you go."

The decision to fire Joe was made by vote of the AV Kentucky staff, 20 to 19. The issue provoked deep soul-searching. Until then, the unspoken AV position had been that they must not talk about issues beyond local ones, as most Appalachian people weren't "ready" to hear about such things as racism and the antiwar movement. Many AVs decided that was wrong, and some resigned to protest Joe's firing. Tom Bethell, a journalist on the AV staff, wrote a parable that was widely circulated. It was about a mythical group called the Bavarian Volunteers in the German mountains in the 1930s. They took the position they should not talk about German war preparations or what was happening to Jews — because people weren't ready. They thought that by about 1942 such discussion might be possible. By that time, the parable pointed out, World War II was in progress and "nobody ever heard of the Bavarian Volunteers again."

While Joe's draft case was developing, the McClellan Committee went after the McSurelys. By coincidence on August 11, 1967, the day of the sedition arrests, the U.S. Senate agreed to McClellan's demand that he be given authority to investigate the black rebellions that jolted scores of American cities that summer. McClellan, an unreconstructed opponent of civil rights from Arkansas, set out to prove the exact opposite of what the Kerner Commission later said; he believed the rebellions were the product of outside agitators and a communist conspiracy.

The three-judge federal court in Kentucky, when it invalidated the sedition law, ordered Ratliff to hold papers taken in the McSurely raid in safekeeping until the time expired during which the state could appeal. The state never appealed — but in the interim Ratliff notified McClellan of the existence of the McSurely papers. Unbeknownst to the McSurelys and their lawyers until later, one of McClellan's staff flew to Pikeville, went through the papers, and took copies of 234 documents back to Washington.

Thus, McClellan found out — among other things — that the McSurelys attended a SCEF board meeting in Nashville in April, 1967, just two days before what he called a riot broke out in Nashville's black community. Actually, the disturbance was rather minor, and was clearly provoked by nervous police. But McClellan was already interested in it, because Nashville police said it had been planned by Stokely Carmichael and the SCEF board. Stokely had been in town that week to speak at Vanderbilt University, and SCEF invited him to speak on the meaning of the Black Power movement then sweeping the country. He did so, presenting a reasoned analysis; he, the McSurelys and all other SCEF people left town 24 hours before the disturbance.

To McClellan, the papers from Pikeville provided the connecting link needed to portray the black freedom movement as a violent subversive plot. There followed the McSurelys' long fight for their papers, their return through tedious court action, and then subpoenas ordering them to turn them over to McClellan. Those subpoenas demanded documents not only related to their own activities but to those of SCEF, SNCC, the Southern Student Organizing Committee, the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party, Vietnam Summer, SDS, the National Conference for a New Politics (the abortive effort to run Martin Luther King and Ben Spock in the 1968 presidential race, which was already being labeled subversive by Senator Eastland), and other groups. In other words, the McSurely subpoenas were aimed at organizations that represented the very heart of the social justice movements of the '60s.

The political implications of that sometimes got overshadowed later in McSurely case publicity — after it was discovered that the papers also included love letters to Margaret from nationally known columnist Drew Pearson. Margaret had an affair with Pearson while working as his private secretary long before she joined the Civil Rights Movement and met Al. The McSurelys revealed the existence of the letters during their contempt trial. By that time, Pearson was dead, and they and their lawyers believed one motive, in addition to political ones, for McClellan's relentless pursuit of them may have been an effort to silence Pearson, who was fiercely critical of the senator in his syndicated column.

Revelation of the letters made sensational newspaper copy — and was painful to Al and Margaret. There were reports that McClellan had passed the letters and Margaret's private diary around for other senators to snicker over. The episode shocked the sensibilities of many people, including jurors in the civil suit won last January.

The civil suit was filed on the morning the McSurelys appeared before the McClellan Committee in March, 1969, and refused to turn over their papers. It took the intervening 14 years to get it through a reluctant court system and win their right to sue and the final verdict. During those years, Al and Margaret moved to the Washington area, where Al now works as a mail carrier and Margaret as a secretary in a hospital. They were divorced in the early '80s, and their son Victor, born in Pike County and almost murdered there, is now 15; he is very supportive of the battle his parents waged.

The victory came 15 years too late to save the organizing Al and Margaret and others hoped to do in eastern Kentucky. SCEF's Mountain Project continued about six years but in other parts of Kentucky and West Virginia. The AV program went on, in weakened condition, for a few years and then disappeared. Control of the antipoverty program was taken over by old-line courthouse politicians.

The pattern of devastation is similar to what happened to black movements that bore the main brunt of this period's repression. SNCC and multiple local movements were crushed. The civil rights thrust was blunted in that period, and the history of the last 15 years in this country might have been very different if it had not been. For one thing, Ronald Reagan might not be in the White House.

To paraphrase the old union saying that "no strike is ever lost," those black struggles of the '60s were not in vain. Beyond the immediate gains of that decade, the ripples started then continued to spread. Although many people were destroyed, others managed to survive and live to fight another day — while younger people influenced by those days went on to build new movements in black communities across the South and the country.

In the same manner, the ripples started in the mountains also spread. There followed the movement for justice by disabled miners and widows, the black lung movement, the effort to reform the United Mine Workers, and continuing work to control strip mining and put severance taxes on coal and other minerals. Although many AVs and VISTA volunteers left the area, some stayed and continued working in other ways. Joe Mulloy, for example, worked for a number of years in the mines of West Virginia, and Karen Mulloy worked in a black lung hospital. They were active in people's movements in that state all during the '70s and are still active today.

In Pike County itself, although many programs were crushed, things will never be quite the same. Edith Easterling, the woman who was at first dismayed by Mulloy's draft resistance, shortly thereafter decided he was right. Easterling was soon fired by the AVs herself for supporting Joe, but continued active in Pike County and now works with senior citizens there. She said recently:

"Joe refusing the draft scared me, but it shook us up, made us think. We needed that. If there had been more people like Joe, maybe fewer people would have been killed in Vietnam. Someday, maybe the people who make the wars will just have to fight them themselves.

"It was hard when Al and Margaret were arrested, but lots of people got educated. Many of us had just accepted it that the courthouse gangs were going to run things. Lots of local people like me wouldn't have ventured out and done anything without people like the McSurelys and the Mulloys. They didn't come tell us how ignorant or dirty we were — like some people who came to the mountains. They talked to us about how we could really help ourselves and change who ran things. Because of those times, now we have black lung benefits, a tax on coal even though it's not enough, the strip mining is slowed down. The main thing is that more people know they can stand up to the politicians and the coal operators."

Sue Kobak, Easterling's daughter, is one of those whose life was changed by the '60s. Sue grew up deeply influenced by the teachings of Jesus through her parents' fundamentalist religion and later by watching civil rights actions on TV. "It was learning about the Civil Rights Movement that made me understand the poverty I grew up in — and the fact that something could be done about it," she said recently.

Sue joined VISTA in the mid-'60s and later married John Kobak, another VISTA volunteer. He died at 24 of cancer his friends believe was triggered by a blow from police during the Poor People's Campaign in Washington in 1968. Later Sue finished college and went to law school. She now practices law back in Pikeville, in a firm that lets her concentrate on helping poor people.

"We were isolated growing up in the mountains," she said. "It was like living in a monarchy that people did not question. It was meeting people like the McSurelys and the Mulloys that made it possible for me to know the rest of the world.

"I remember one of the first times I saw Al. He was talking about some wild scheme he had thought up — something about a national transportation system, using tubes. Al was always coming up with wild ideas. I think he did it to draw attention to problems. But I was impressed — just knowing that somebody had the nerve to think that way and say it out loud. It was the first example of creative thought I'd ever encountered."

It was people like the McSurelys and Mulloys, Sue says, that enabled her to get out — out of the mountains and old ways of thinking. And it was the battle the McSurelys put up that enabled her to come back, to practice law. Could what happened in 1967 happen again?

"Not in the same way," Sue says. "The publicity focused on Pike County really embarrassed people here. But it could happen — it would just be more subtle now. I still don't know whether I'll be able to stay. But I want to; I'm back by choice now."

As for Al and Margaret, they both believe the long fight they made was worth all they went through.

"They succeeded in stopping us from organizing in Pike County," Margaret said, "but I believe this fight opened the way for others to organize and do political work. I hope many people will take advantage of our victory."

For Al, time and the struggle have only reinforced the ideas that took him to Pike County in the first place. He says:

"The vision we and others had in the '60s of poor and working white people organizing to form coalitions with the black movement was a revolutionary idea. Ratliff knew that, the people who ran Kentucky knew it, the FBI knew it, McClellan knew it. That's the bottom line. I hope that people on our side know it too, because it's just as valid an idea now as it was then, and now may finally be the time when it can be done."

* Among the lawyers who worked on the varied criminal and civil aspects of the long Pike County struggle were Pikeville attorney Dan Jack Combs; Center for Constitutional Rights lawyers Bill Kuntsler, Morton Stavis, Arthur Kinoy, Nancy Stearns, Randolph Scott-McLaughlin, and Victor McTeer; Kentucky Civil Liberties Union general counsel Robert Sedler; and many other volunteer lawyers and law students who helped along the way.

Tags

Anne Braden

Anne Braden is a long-time activist and frequent contributor to Southern Exposure in Louisville, Kentucky. She was active in the anti-Klan movement before and after Greensboro as a member of the Southern Organizing Committee. Her 1958 book, The Wall Between — the runner-up for the National Book Award — was re-issued by the University of Tennessee Press this fall. (1999)