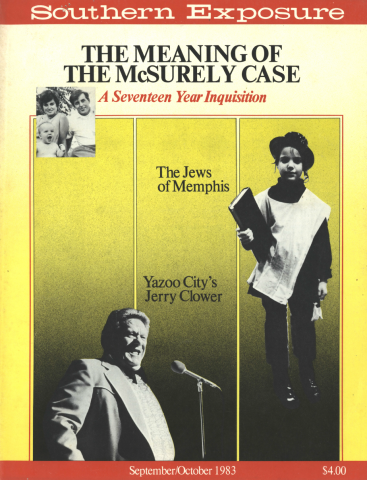

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 5, "The Meaning of the McSurely Case: A Seventeen Year Inquisition." Find more from that issue here.

During the post-emancipation era, many black Southerners fled the increasing racial restrictions and violence that accompanied and eventually ushered out Reconstruction efforts. But even in the strife-torn days of 1888, the Hawkins family found the decision to leave difficult. They had lived in relative comfort on and near the North Carolina plantation of John D. Hawkins, a famous English navigator. Economic and social aspirations overrode emotional attachments, however, and six-year-old Lottie Hawkins moved with her family to Cambridge, Massachusetts, where opportunities were more accessible to blacks.

With the generous support of Alice Freeman Palmer, the first woman president of Wellesley College, Charlotte Eugenia Hawkins (she changed her name in high school), was able to attend the State Normal School at Salem, Massachusetts. But at the end of the first year of the two-year course of study, she interrupted her college education at the invitation of the American Missionary Association [AMA] to teach at its Bethany School in Sedalia, North Carolina.

The AMA's tradition of teaching free black Southerners, dating back to 1861, had shifted by the end of Reconstruction from providing white teachers to supporting blacks to teach and administer schools. This record made the opportunity seem promising and induced Hawkins to return to the state of her birth. But upon her arrival in 1901, her romantic notions about teaching were dispelled by the responsibilities of running a dilapidated, ill-supported country schoolhouse. Moreover, less than a year after her appointment, the AMA withdrew its financial support, leaving the 19-yearold teacher to face the challenge alone.

In response to the urgings of community members, as well as to the promptings of her own ambition, Hawkins remained in North Carolina and began a solo fundraising campaign to open an independent school. The doors of the Alice Freeman Palmer Memorial Institute, named for her benefactor, were opened in 1902 to "conduct and maintain an institution for the colored race . . . to teach improved methods of agriculture." By the early 1940s, the educator had changed the school's emphasis from agricultural and industrial training to liberal arts — hardly an easy task to accomplish in an age openly hostile to black education.

As an educator and social reformer, Hawkins, who became known as Charlotte Hawkins Brown after her short-lived marriage to Edward Sumner Brown in 1911, was dedicated to improving both the status and the image of black women. She helped organize the North Carolina Federation of Negro Women's Clubs in 1909, and served as its president from 1915 to 1936. The reformist group's mission was to educate and "uplift" the black race.

Brown was also active in the Southern interracial movement from 1920 to 1946, serving as an "ambassador" for her people and attempting to dispel the pervasive notion of the moral and intellectual inferiority of blacks. She believed — and taught — that if Negro women would learn to act like ladies, they would be treated as such. Addressing the "young girl who wishes to make her wheels of life run smoothly," Brown described the "earmarks of a lady" in her book, The Correct Thing To Do To Say To Wear. According to Brown, a lady must be "considerate, not overbearing or dictatorial. She must give the boy plenty of room to be gracious, chivalrous. . . . So many of the rungs of the ladder of old time chivalry [have been destroyed by the] cultivated familiarity on the part of the average girl or woman, with men nowadays."

Brown's own life stands in contradiction to the Victorian sexual and social mores she extolled in The Correct Thing. Though her definitions of "normal" womanhood included marriage, she was single during all but two years of her life. She founded Palmer Memorial at the age of 19, and by 1941 when The Correct Thing was published, she had developed the school to the heights of national prestige. The nature of her work in education and social reform required that she manifest many of the "masculine" qualities she denounced as inappropriate for proper ladies. Moreover, "old time chivalry" had never existed for Brown nor for any other black woman in America. The complexities of her times, the ambiguities evident in her life and work, can be traced through the record of Charlotte Hawkins Brown's efforts to sustain her' school and serve her people.

"In my efforts to get money now I don't want my friends to tie my hands so that I can't speak out when I'm being crushed. Just what are they going to ask me to submit to as a Negro woman to get their interests?"

Brown wrote these words as she faced a dilemma common to all black educators: how to obtain money from white resources, maintain self-respect, and build a school more attuned to black needs and preferences than to those of white supporters. She could have pumped jugs of water from an arid field more quickly than she could have attracted white supporters in North Carolina at the turn of the century. Expressing the state's sentiments, Governor Charles B. Aycock said, "Education for the whites will provide education for the Negroes." Even the progressives who intervened to upgrade the lagging public school system supported Aycock's osmosis theory. They formed the Southern Educational Board in 1901 to ensure an efficient flow of Northern and Southern philanthropic capital to education in the South. But the board accomplished fiscal savings by directing funds away from Negro schools toward schools for whites.

Brown's most immediate challenge in attracting funds from philanthropists was to present Palmer Memorial as a place where the minimal dollar would go far, but not further than a black child's prescribed lot. An early school brochure pictures a young boy dressed in overalls, a tattered shirt, and a knapsack, standing on a dusty, barren road. "The students are poor but ambitious," the caption explained. Another shows an older boy repairing a motor vehicle: "The students graduate with a practical education." These brochures were designed to convince potential donors that Palmer Memorial was a worthy cause and to allay white fears that education would spoil blacks as service workers.

Persistent pleading and self-effacement characterized much of Brown's role as fundraiser. Her mother had warned her that whites "can make you or break you." They sometimes did both. The thin line between racism and liberalism surfaced often in Brown's attempts to juggle personal and business relationships with white women. A letter from Francis A. Guthrie, an early white supporter and long-time friend, reflects Brown's predicament. Do not teach "your boys and girls more than at present their natures are ready to receive," Guthrie advised Brown. "Your pupils are not like you, have not had your bringing up." She warned Brown that the students' parents, who were "nearly all very ignorant people," would resent their children being offered academic subjects.

Besides revealing a frequently expressed fear that blacks would rise above racially imposed limitations and no longer "work at the hard drudgery of everyday work," Guthrie's admonitions demonstrate her ignorance about black attitudes toward education. (She was apparently unaware of the sacrifices and hard labor that "ignorant" blacks were willing to endure for the education of their children.) She advised Brown to teach morality instead: "Make it impossible for the young girls of your race to be so weak and hold their virtue so cheap. Christ would prefer this." Christianity was often used to justify racist policies when whites gave and blacks received.

Helen F. Kimball, another white donor and friend, had warned Brown to slow her efforts and concentrate on more "practical" plans. Brown apparently did not take her advice and needed money to pay debts. When Brown approached her for a $ 1,000 donation, Kimball reprimanded her for constant begging and bad business methods. Furthermore, she asked, "Do you get help from your own race?"

Getting more help from her own race, and thus cutting down on the humiliation of seeking funds from patronizing and often dictatorial donors, was Brown's ultimate goal. But she was hindered by the constant need for immediate funds to keep the institution afloat and by the lack of resources in the black community, barely a generation out of slavery when she opened her school in 1901. In 1924, the AMA agreed to renew its support at the end of five years only if Brown could raise a total of $150,000, plus matching funds for current expenses. Brown managed to keep her part of the deal. But in 1932, it became evident that the AMA objected to the shifting nature of Palmer Memorial's development. Liberal arts had become an increasingly important part of the school's curriculum, and Brown had seriously considered adding a junior college. The AMA politely but emphatically bowed out. This lack of sponsorship forced Brown to reorganize the board of trustees, paying particular attention to the details that would again attract Northern philanthropists.

Once reestablished, with a prominent white male Southerner at its head, the board accepted many of the financial responsibilities that Brown had shouldered alone. Yet the school continued to suffer from financial instability. In 1939 Brown reported with dismay, "We have lost 500 contributors in the period of three years — people whose finances have been reduced to the place that they feel they cannot even spare one dollar."

In an apparently desperate attempt to gain state support, Brown proposed to train "refined, intelligent leadership from [women among] the Negro group" as domestic workers to "release the busy [white] woman for civic affairs." Brown asked that North Carolina acquire Palmer Memorial to serve as the "women's department" for freshmen and sophomores at North Carolina College for Negroes (NCCN) in Durham. She sought favor for the plan on behalf of uplifting the declining morality of black women and their status in domestic employment.

According to Brown, rural Southern black women had not received the correct cultural training for developing "wholesome" characters or the "right attitudes toward life." And since men outnumbered women substantially on black college campuses, the uncultured women were exposed to the "natural evils resulting from such conditions." If the state acquired Palmer Memorial, she argued, more blacks could learn to become "fine, clean mothers" and "good homemakers for themselves and for others." As busy white women entered public arenas, professional black women would manage their homes, "oversee the unskilled," and receive salaries comparable to those of teachers. The proposal aimed to assure whites that black women would continue to be confined to domestic service, and to make such employment appear glamorous enough to appeal to blacks.

Although Brown had persistently defied whites' attempts to limit her school's curriculum, she was now sacrificing her ideals of black education for the school's financial survival. But state officials must have looked askance at this offer to "release" white women, for they rejected the proposal to merge Palmer Memorial and NCCN, claiming that the distance between Sedalia and Durham made the proposition too expensive. (A similar plan was vetoed a year later in 1940, substituting Bennett College in Greensboro, Palmer Memorial's neighbor institution.)

The state attempted instead to create a new agenda for the black institution. It would gladly make Palmer Memorial a home for "delinquent colored girls." Brown herself had helped perpetuate the negative stigmas attached to black women through her emphasis on their so-called immorality. Yet she frowned on the state's plan, explaining her response this way:

To tell the truth, after forty years of trying to help boys and girls with a desire to do something to go forward . . . to turn my whole attention to incorrigibles was more than I could do. I have neither the strength nor the ability to cope with the situation.

Nor the desire, one might add. At this point in Palmer Memorial's development, certain kinds of youth were clearly unwelcomed. Admissions applications, in fact, italicized the stipulation that "incorrigibles need not apply."

Brown's rejection of the state's proposal to incarcerate "incorrigibles" signalled the beginning of a new Palmer Memorial, quite unlike the image presented in the earlier brochures. Despite Brown's attempts to mollify white patrons, she still maintained her own dreams for black education. After all, her own education had not been shaped by Jim Crow. At the Cambridge English High School back in Massachusetts, she had acquired the same academic and social rudiments that prepared her white peers for mainstream American life. Her New England background provided a vision upon which she was to build Palmer Memorial into a college preparatory school for the fledgling black elite.

Missionary support had failed, philanthropy had subsided, and state support had been denied. Brown turned to "her own people for support," as she had been advised to do. But the number of blacks with resources to support the school were few and their resources scant compared to the more established whites on whom she had previously counted for sponsorship. Funds from blacks came to Palmer Memorial in the form of tuition. In "A Brief Annual Report (1940-1941)," Brown reported that Palmer Memorial had "made a record here unparalleled by any Negro school in the South in the percentage of [tuition] collections from the student body." The number of North Carolinians in attendance decreased as the character of the student body became more urban and national than rural and local. Open admissions became competitive as hundreds of applications poured in to fill the few yearly vacancies.

The ability to pay tuition was a major criterion for selection, for without that income the school could not survive. Selection standards also included such euphemisms as "aristocracy of character" and "Christian background" which could readily be utilized to exclude the poor, the majority. This elite constituency of black students did not travel across the country to learn "improved methods of agriculture." The publication of The Correct Thing in 1941 reflected the fact that Palmer Memorial had become a co-ed finishing school which emphasized "smoothing the rough edges of social behavior."

However triumphant these changes may have seemed, they had larger implications for black education. The new Palmer Memorial was certainly not what white supporters had in mind as "practical" education for blacks. Instead, the school imitated what whites considered the best for their own children, offering students a wide range of academic courses plus extracurricular activities which included European study trips and participation in the acclaimed Sedalia Singers. But molding character remained foremost in the mind of the founder and principal. Brown instilled the kinds of postures and attitudes that would promote socio-economic mobility into the American mainstream. Black students were encouraged to look, talk, and act according to standards of behavior most pleasing and least repulsive to white society.

Palmer Memorial's new agenda was more attuned to early twentieth century thought than to the growing democratic consciousness of the World War II era. In the earlier era, black educators, regardless of seemingly conflicting views on "practical" versus "classical" education, agreed that the talented and educated few must bear the responsibility of changing the lot of the many. The political thrust for universal education had been crushed under the heels of Jim Crow, along with other progressive social reform measures enacted under the brief Reconstruction era governments. Educated and uneducated blacks alike expected the privileged few to utilize their influence, knowledge, and resources to bring justice and prosperity to the race.

The failure of the "talented tenth" to bring about the expected changes led to dissension. Though Brown must have felt that she was contributing to the redemption of her race by providing her select group of students with opportunities generally reserved for whites, she actually helped lay the foundation for class schisms which continue to plague the black community in these latter days of the twentieth century.

"If I can only render services to both races and if I can have the confidence of both races there may be accomplished some things that we all desire to see accomplished. "

Using the podiums of women's clubs and interracial organizations, Brown tried to annihilate the myths that intelligence, morality, and femininity were racially predetermined. Certain black women were just as good as white women, she would argue. But in this very attempt to attack racial and sexual stereotypes, she furthered their continuance. Certain blacks could become just as good as whites, she said, if taught the canons of "proper" behavior as defined by white society. The ambiguous role Brown played in early twentieth century reformism is suggested by conflicting views of that role expressed by two of her male contemporaries. Will Alexander, the white founder of the Commission on Interracial Cooperation [CIC], found her "full of fire and resentment, and eloquence," while W.E.B. DuBois, black educator and a founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People [NAACP], declared that "Charlotte Hawkins Brown represents the white South."

Brown had inherited the Victorian sexual values adopted from whites by middle-class black women who pioneered a movement to organize local, regional, and national organizations in the late nineteenth century. The club women selected "Lifting As We Climb" as the motto of their campaign to correct the moral "deficiencies" of the black masses in order to ensure the entrance of a "better class" of blacks into mainstream American culture. Brown articulated these same ideals as she herself came to political maturity as an interracial mediator in the troubled post-World War I South.

Periodically, however, when stunned by the frequently brutal reality of being black and female, Brown spoke out with candor and courage against sexism and racism. One such occasion was the first women's interracial conference sponsored by the CIC in Memphis, Tennessee, in October, 1920. On the train trip to the conference, Brown experienced what she often called one of the most humiliating incidents of her life. Before leaving the Greensboro station, she made arrangements to occupy a car with sleeping facilities. "I had just opened school that day and had been working hard all day," she remembered. "I wasn't going into that sleeper because I wanted to be with white people." White male passengers objected to her presence, nonetheless, demanding that she transfer to the Jim Crow car. She angrily obeyed. Walking behind her humiliators, she became even more furious when she spotted complacency on the faces of the white women who sat by unmoved.

Brown arrived at the conference bitter, angry, and hurt. When invited to take the speaker's podium, she related the incident in a straightforward speech that left the predominantly white group of women spellbound. To give them an idea of the helplessness she had felt she challenged her audience to entertain the idea of being colored and paralyzed. From her own immediate experience, she moved directly to the issue of lynching — the most often avoided topic in interracial groups. "The Negro woman lays everything that has happened to the members of her race at the door of the Southern white women. You can control your men," she said, and stop lynchings.

As if reminding white women of their responsibility to curb racial violence was not sufficiently unnerving, Brown went on audaciously to exhume one of the most deeply buried ironies of Southern tradition: "When you read in the paper where a colored man has insulted a white woman, just multiply that by one thousand and you have some idea of the number of colored women insulted by white men." Brown's anti-lynching message attacked the region's persistent blindness to the historically forced sexual relationships between white men and black women, contrasting this with the prevalent exaggeration of the threat that black men posed to white women. Sex, or the mere thought of sexual relations, between black men and white women was culturally defined as "rape," and was used to justify mob violence. Brown concluded, "Won't you help us, friends, to bring to justice the criminal of your race . . . when he tramps on the womanhood of my race?"

Though few white "friends" were prepared to challenge tradition. Brown was still determined to test Southern justice, and filed suit against the Pullman Company for the painful insult she experienced on the train. In retrospect, she never described the indignities she suffered in the suit. As she recounted the incident, "My Southern lawyer, taking no percent of the recovery, sued and won."

Actually, Brown's memory of the incident was somewhat faulty. Whether because of the pain of the memory or out of respect for her lawyer and trustee, Frank P. Hobgood, she made no mention of the racist and sexist implications of his attitude. He approached the Pullman Company for $3,000, but the company refused to pay more than a paltry $200. The request must have seemed ludicrous to them, for black women were so severely stigmatized that white men who "insulted" black women did so within their historical rights. While Hobgood rejected the company's concessions, he questioned the validity and "wisdom" of Brown's decision to file suit. Was it worth the risk of provoking "vexacious questions" about the morality of black womanhood, he asked? The attorney advised Brown to reduce her demand to $1,000 in hope of receiving $500: "If this sum is offered you had better accept it. . . . I think it is fair, in the event of any amount . . . my fee should be 50 percent."

No thought of chivalry entered the minds of the men who refused to allow Brown to rest in the sleeping quarters, though she was facing a 650 mile trip and had worked all day. Nor did thoughts of chivalry motivate her lawyer or any other man. Anna J. Cooper, another black Southern educator, articulated the need for feminist consciousness among black women when she wrote in 1892, "Confronted by both a woman question and a race problem, [the black woman] is as yet an unknown or unacknowledged factor in both."

If the Pullman incident and legal suit did not prove this to Brown, painful encounters within the black community should have. Black men who lived near her school voiced suspicions about Brown's relationship with her white male trustees. Attitudes in the black community tended to blame the past victims of rape and concubinage for their own victimization. Not only whites, but blacks too failed to question the validity of the stigma of immorality that branded the women. The suspicions expressed about Brown attest to the endurance of that stereotype and represent but one of the many obstacles she had to overcome in order to keep her school afloat.

In Brown's attempts to steer the public away from the image of the "loose woman" and the "bad" Negro, she adopted condescending attitudes of her own. "Until women in our group on the lowest rung of the ladder economically and morally are unshackled from fear and unfettered in their attempts to breathe in an atmosphere of freedom," said Brown, "all Negro women are slaves." But class bias undergirded this apparent recognition of the powerlessness of all black women and their inevitable connection with each other. By implying that black women were morally inferior, Brown failed to challenge the validity of white accusations. Instead, like other reform-minded people of her generation, Brown attributed the negative racial and sexual stereotypes to immorality among the "lower" classes, rather than to white biases and abuse. No black female could be free from humiliating insults, she argued, until those at the bottom had been cured of their social and cultural retardation.

In the meantime, Brown demanded the distinction she considered her due, as one of the morally and culturally "advanced" Negro women. Having lifted herself "through 50 years of training and service from that class . . . prostituted years ago to save the women of the white race," Brown sought to be "separated somehow or other from the other type of colored women." These sentiments were expressed so often by Brown and other black women during their involvement with the Southern interracial movements of the 1920s, '30s, and '40s, that white women began to regurgitate the message. Carrie Parks Johnson, a Methodist women's leader in this period put it this way: "We know the worst there is to know — but the masses of the best of my race do not know the best of the Negro." Getting to know the best of the Negro race became the limited basis of interracial work with the approval of many blacks as well as whites, a tradition which hinders interracial work even in the 1980s.

Believing that in the white mind, the image of the "best" Negro woman could be characterized only by a vivid and glorified memory of the plantation "mammy," Brown tried to evoke this image to gain white recognition of the virtues of black women. In Mammy: An Appeal to the Heart of the South (published in 1919), Brown wrote:

If there is any word that arouses emotion in the heart of a true Southerner, it is the word, "Mammy. " His mind goes back to the tender embraces, the watchful eyes, the crooning melodies which lulled him to rest, the sweet old black face.

Few white Southerners actually had black mammies, but they became a composite, imaginary figure for whites who desired to identify with the aristocracy of the antebellum South. An actual member of Southern aristocracy, Fannie Y. Bickett, wife of the governor of North Carolina, introduced Brown at the CIC Continuation Committee of the Women's Interracial Conference in 1921. Establishing the importance of her memories of plantation life, Bickett stated, "My old Negro mammy . . . was to me a mother . . . [I am grateful to find a likeness of] the virtue, the truth, the loyalty, and the fineness of purpose in another generation of Negro women." She commended Brown for her work in clubs, churches, and communities. But, Bickett continued, more important was "the work she is doing for the young girls of today." Then she added affectionately, "I cannot say more, Mrs. Brown, for your race today than I say in saying that you are as fine as my Negro mammy."

To call a twentieth-century black woman "mammy" was an outrageous insult. Yet Brown graciously, or expediently, accepted the condescending gesture as a compliment. She responded, "I want to thank my good friend . . . for the splendid things she has said about me. . . . I hope and trust too that I am measuring up in every way to what the white people . . . think of me." And then she quickly added, "In doing so I am by no means betraying the confidence of my people." Incidents like these, however, marred Brown's reputation among her people, often prompting outraged verbal attacks against her.

When Brown wrote Mammy two years before the Bickett incident, her purpose was to encourage whites to recognize and show appreciation for their faithful black servants. Brown's story is about an Aunt Susan, who dedicated her life to serving a white family in slavery and in freedom. When she became "old and no count," the whites allowed her to die destitute. One can easily draw important parallels between Brown and Aunt Susan: the mammy embodied qualities similar to Brown's, which made her an honorable black woman on the plantation. The mammy symbolized faithfulness, persistence, strength, and endurance. Having acquired the deportment and been allotted some of the dignity of the master class, she served as a buffer between the races. Since she represented the interests of whites, she helped to stabilize the slave system by enforcing the social behavior that whites preferred, thereby protecting the slaves from the wrath of the whites and sometimes gaining special favors for herself and for the other slaves.

Such was the nature of the ambivalence that characterized Brown's participation in Southern social reform. Yet one thing remains clear: by participating in the ritualistic interracial gatherings, Brown hoped to win social legitimacy and financial security for her school. In these goals she succeeded, although the successful application of the principles she set forth in The Correct Thing eluded her all her life. Ladies were supposed to be modest in expressing "negative" emotions, if they expressed them at all. Brown's strength, endurance, and ambition caused her contemporaries to question how a proper lady could manifest such "masculine" attributes without threatening her own femininity or someone else's masculinity.

Brown's unpopular qualities certainly conflicted with the image of the lady she tried so vigorously to create; yet these qualities were political necessities. No black institutions could be built, no racist barriers could be overcome without them. Success and survival demanded that she not subdue her personality. The actual life of Charlotte Hawkins Brown, rather than the one she attempted to portray, often bore the marks of a person struggling to be a freer and more complete human being. If there is a tragedy in Brown's life, it is not that she lived a reality different from the image she projected, but rather that she failed to recognize and understand this dichotomy and its positive racial and feminist implications.

Tags

Tera Hunter

Tera Hunter, a native of Florida, graduated from Duke and will be attending Yale. Photos were collected by Studio Five Productions, which produced a video history of Palmer Memorial Institute. The history is free for short-term use from the NC Humanities Committee, UNC-Greensboro, or call Studio Five at (919)272-3149 for rental or purchase information. (1983)