Freedom or Affluence

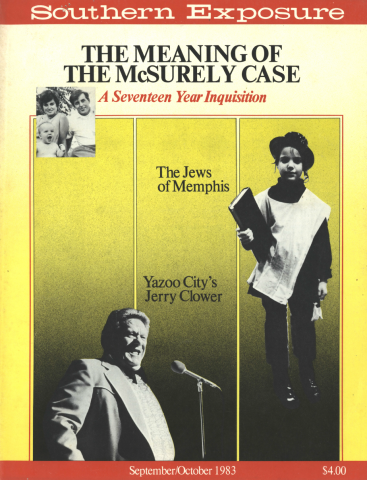

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 5, "The Meaning of the McSurely Case: A Seventeen Year Inquisition." Find more from that issue here.

When Thomas Hamilton founded the Anglo-African Magazine in New York in January, 1859, the battle between pro- and anti-slavery forces was at its height. Free blacks agitated and petitioned on many fronts to bring about the demise of slavery and were becoming increasingly militant in the face of the Supreme Court's Dred Scott decision, Fugitive Slave laws, Compromise bills, and the continued denial of citizenship on the part of federal and state governments. In addition to exposing the condition of blacks in the United States, Hamilton hoped to "encourage the now depressed hopes'' of those who "for twenty years and more have been active in conventions, in public meetings, in societies, in the pulpit, through the press, cheering on and laboring on to promote emancipation, affranchisement and education." In the midst of escalating legal sanctions against blacks, both slave and free, some professional and middle-class blacks still ascribed to the goals and values of the ruling class. Frances Ellen Watkins used the pages of the Anglo-African in May, 1859, to speak out against this phenomenon and to warn blacks against the futility of individual enrichment at the expense of fellow blacks still held in slavery. We find her message particularly timely as the election season approaches and certain segments of current black leadership prepare to sell the black vote to the highest bidder.

When we have a race . . . whom this blood-stained government cannot tempt or flatter, who would sternly refuse every office in the nation's gift, from a president down to a tide-waiter, until she shook her hands from complicity in the guilt of cradle plundering and man stealing, then for us the foundations of an historic character will have been laid. We need men and women whose hearts are the homes of a high and lofty enthusiasm, and a noble devotion to the cause of emancipation, who are ready and willing to lay time, talent and money on the altar of universal freedom. We have money among us, but how much of it is spent to bring deliverance to our captive brethren? Are our wealthiest men the most liberal sustainers of the Anti-slavery enterprise? Or does the bare fact of their having money really help mould public opinion and reverse its sentiments? We need what money cannot buy and what affluence is too beggarly to purchase. Earnest, self sacrificing souls that will stamp themselves not only on the present but the future. Let us not then defer all our noble opportunities till we get rich. And here I am, not aiming to enlist a fanatical crusade against the desire for riches, but I do protest against chaining down the soul . . . to the one idea of getting money as stepping into power or even gaining our rights in common with others. The respect that is only bought by gold is not worth much. It is no honor to shake hands politically with men who whip women and steal babies. We have the greater need for . . . [our children] . . . to build up a true manhood and womanhood for ourselves. The important lesson we should learn and be able to teach, is how to make every gift, whether gold or talent, fortune or genius, subserve the cause of crushed humanity . . . and carry out the greatest idea of the present age, the glorious idea of human brotherhood.