This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 5, "The Meaning of the McSurely Case: A Seventeen Year Inquisition." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

The following article contains references to sexual assault.

Rachelle Saltzman was director of an Ethnic Heritage Project at the Center for Southern Folklore in Memphis, Tennessee. All interviews cited here were completed as a part of this project during 1982 and are the property of the Center for Southern Folklore. The research for this article was made possible by grants from the Department of Education, Title IX, the Ethnic Heritage Studies Project; the Hohenberg Foundation; and the National Council of Jewish Women, Memphis section.

Memphis, Tennessee, is not a place where one would expect to find a thriving Yeshiva (Hebrew high school), a Jewish community center that hosted the 1982 International Jewish Junior Olympics, or a restaurant with a name so redolent of mixed cultures as "Johann Sebastian Bagel." But the city with "more churches than gas stations," home of Elvis Presley and Beale Street, as well as the site of Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination, is also home to over 8,000 Jewish families.

Formal Jewish identification is typically higher in the South than elsewhere in the United States. According to a 1981 "Memphis Jewish Family Life Survey" by the local chapter of the American Jewish Committee, more than 90 percent of Southern Jews are synagogue members, compared to fewer than 80 percent in other parts of the country. Moreover, Southern Jews share ties with Jews elsewhere. Several social and fraternal organizations encourage visiting among cities, states, and even regions of the country. B'nai B'rith (for men, women, and children), AZA (a boy's social organization), Hadassah (for women), Hillel (a college youth group), Jewish community centers, and synagogue auxiliaries all provide outlets for social life, charitable obligations, and ethnic awareness.

In Memphis, and in other Southern cities, the Jewish community includes fifth-generation Jews whose ancestors came to the city before the Civil War; second- and third-generation Eastern European Jews; new immigrants from the Soviet Union; and many from other diverse backgrounds. Their religious practices vary, too, from the ultra- Orthodox (the most strictly traditional) to the more modern Reform tradition. Four congregations cover this spectrum.

A good example of their religious diversity is the way Memphis Jews celebrate Purim — a sort of Jewish Mardi Gras — during which men dress up as women and vice versa; drunkenness (until one cannot tell the difference between the hero and the villain of the Purim story) is prescribed; and carnivals, games, and a general good time are enjoyed by young and old. Purim commemorates the escape of the ancient Persian Jews from genocide, thanks to the victory of the Jewish Queen Esther and her uncle, Mordecai, over the wicked prime minister, Haman.

The holiday begins at sundown, as do all Jewish festivals. Congregations listen to the reading of the Megillah, the scroll of Esther. Whenever Haman's name is mentioned, children and adults alike twirl noisemakers to drown out the sound of his wickedness. After the service, refreshments are served. Carnivals and parties take place the following day (or on the nearest Sunday for most modern congregations).

At Memphis's Orthodox synagogue, Baron Hirsch, men and women sit separately, as they do for all services, divided from each other by a wooden screen. The rabbi and cantor unravel the scroll and read the Purim story in Hebrew, while small children wander about, twirling their noisemakers. At Temple Israel, the home of the Reform and oldest congregation in Memphis, the two rabbis and the cantor prance in costume about the bima (raised platform at the sanctuary's front) and act out the story in English. Families sit together; adults as well as children are often in costume. The atmosphere is that of an informal play — of participatory theater — rather than of a sombre religious occasion.

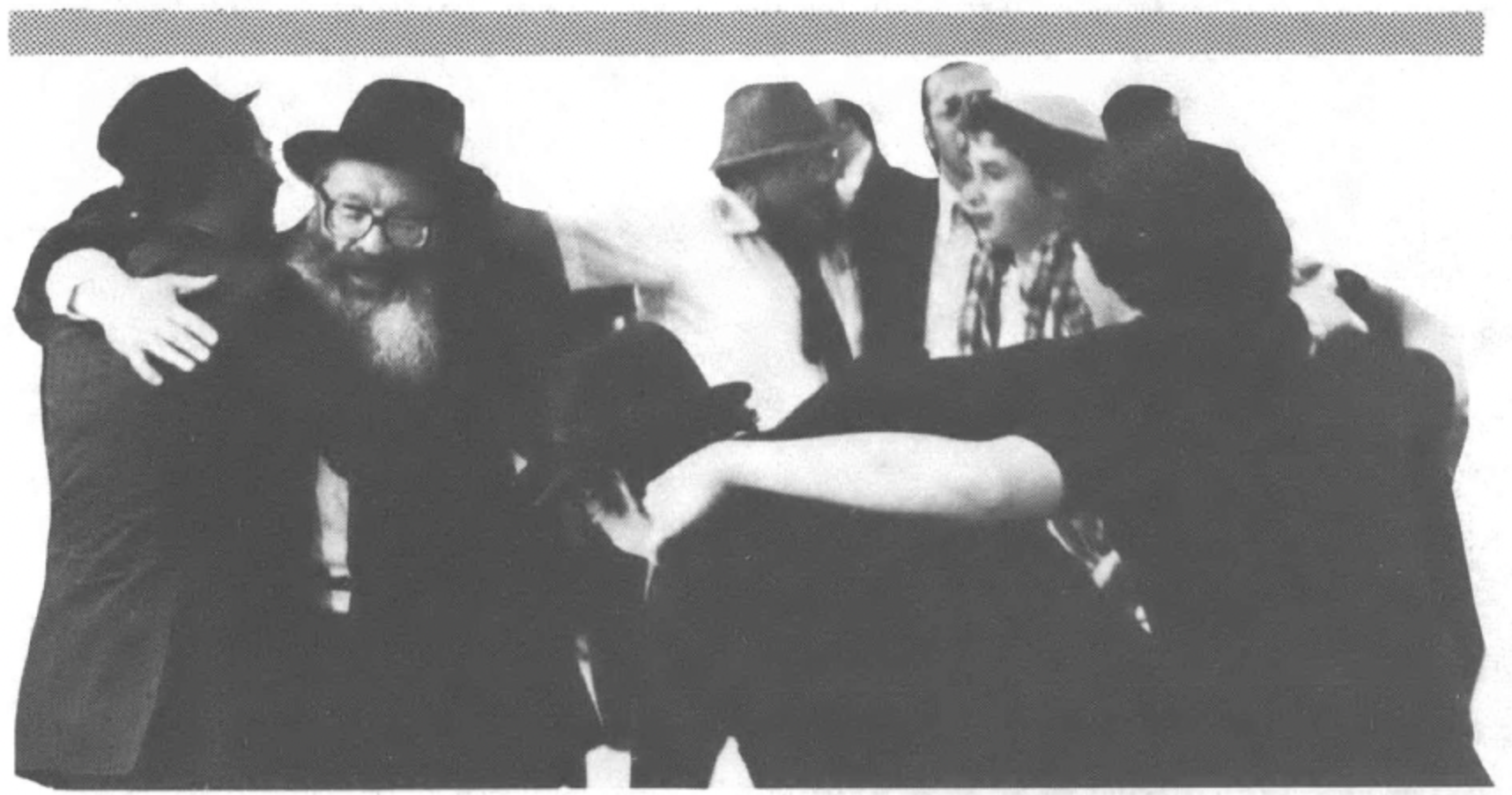

The following day more raucous behavior occurs at the Yeshiva of the South, where the ultra-Orthodox Jewish community of Memphis takes literally the injunction to drink until one cannot tell the difference between Mordecai and Haman. Between courses of the holiday meal, men and a few children dance with abandon to traditional Jewish music. Wives sit and tolerantly observe their menfolk. When asked why they are not drinking too, they say that someone must stay sober in order to get the rest of the family home that night.

At the Jewish Community Center on the Saturday night following Purim, a more sedate group of adults representing several congregations celebrates the occasion with a costume party and dinner-dance to pop tunes. Interestingly, the band there is the same group that played for the party at the Yeshiva. But at that institution they had performed traditional Jewish folk songs. The two events demonstrate the contrast between the more assimilated Jews of Memphis, most of whose families have lived in the South for three or more generations, and the far more traditional members of the Yeshiva, many of whom have come to Memphis fairly recently.

The variety of costumes displayed at the different Purim carnivals highlights the diversity within Memphis's Jewish community. At Anshei Sphard-Beth El Emeth synagogue, a young girl dresses up as a chasidic boy (a sect of very religiously observant Jews) in his traditional outfit — complete with tzit-tzit (prayer undergarment), payess (side curls), and siddur (prayer book). The child represents not only the contradictions in this particular Southern Jewish community, but those within American Judaism: a girl acting as a boy, a less religiously observant Jew dressed as an ultra-orthodox one, and all on a holiday that emphasizes disorderly, "upside-down" behavior. Like this child, Memphis Jewry is a mixture of traits from over 5,000 years of tradition, of Western and Eastern European customs, of Reform, Orthodox, and Conservative theology, and of the influences of American culture on an ethnic community in the rapidly changing South.

Jews first came to the South before the American Revolution. Most were of Sephardic (Spanish, Southern European, or Middle Eastern) background, and they often settled in port cities such as Atlanta, Charleston, and New Orleans. Jews first came to Tennessee in the 1790s and to Memphis in the 1830s, '40s, '50s, and '60s. They were a part of the Western European wave of immigration to the United States caused by political and economic upheavals in Europe during the mid-nineteenth century. Since, for several hundred years, Jews had rarely been permitted to own land in much of Europe, many became adept in the only occupations left open to them — commerce, moneylending, and intellectual endeavors. These skills were readily adaptable to their new homes in America.

Although some trade and residency restrictions existed for Jews in American colonial days, by the mid-nineteenth century, such restrictions had been largely removed. As a result, many Western European Jewish immigrants joined other newcomers who followed trade routes and set up businesses in the Midwest and South. Some began as small-time peddlers, who increased their wares and incomes by selling much-needed goods to settlers in what were then frontier outposts.

In Memphis and nearby rural areas, most Jewish settlers came from middle-class business families, who were able to set themselves up as merchants, tinners, clerks, sawyers, clothiers, bankers, cotton brokers, tailors, and painters. According to Herschel Feibelman, a prominent Memphis lawyer, members of his family, who came to the mid-South in the nineteenth century, "were primarily engaged in mercantile business. I can't say that there was anything of the traditional start where they were peddlers. I rather believe that they were people who had some means and quickly acquired the status of a merchant doing business in a locale, out of a store." Gilbert Delugach, a Memphis businessman, says:

The German Jewish population, which had such well-known names as Lowenstein, Goldsmith, Bry, Block, Halle, Summerfield, Oppenheimer, [and] Dinkelspeil . . . were associated with mercantile establishments. Seessels were in the food business. Boshwits were in the real estate business. . . . The Peres family in the food brokerage business helped start the early synagogue which became Temple Israel.

Religious matters as well as business affairs were of concern to the first Jewish settlers in Memphis. As in other places, one of the first institutions they established was a burial society — a necessity, for Jews could not be interred in Christian cemeteries. These new settlers also took care of the living members of the community and, by 1850, had founded a Hebrew Benevolent Society so that needy Memphis Jews would not be a burden or an annoyance to the city. The creation of both these institutions demonstrated a sense of group solidarity evidenced by many immigrant and black communities throughout the U.S.

Jewish community identity further manifested itself with the organization of a synagogue, B'nai Israel, or the Congregation of the Children of Israel, in 1854. Although an actual building is not a requirement for Jewish congregational worship, the formal establishment of a house of worship expressed a certain material success, as well as a desire for a more visible display of identity in this new homeland. Further proof of the Memphis Jewish community's growth came in 1865 with the formation of a second congregation, Beth El Emeth, by people who wanted to preserve more traditional practices as B'nai Israel became more "Americanized."

The last quarter of the nineteenth century brought change to the Jews of Memphis. Three waves of yellow fever epidemic in the 1870s devastated their numbers; many either left the city for healthier areas or died. But an influx of new immigrants from Eastern Europe between 1881 and 1921 helped to prevent the city's Jewish community from dying out.

Jews left Eastern Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries for a variety of reasons. Many fled as a result of pogroms (officially sanctioned and organized persecutions), military conscription, and poor economic conditions. Gilbert Delugach recalls:

My grandfather, who was unsuccessful in general business, became a smuggler of people because a great many wanted to leave and were unable to leave Russia. It was Russian Poland then, legally, so they would be smuggled out — and that is how my father came out — he was almost 16 years old and they thought that he being the oldest in the family, he would have to go into the Russian army, which no Jewish person ever wanted to do, because the life was miserable for a Jewish person in the Russian army. So, one night he climbed in the wagon, under the straw, and was smuggled out by his father.

Ben Sacharin, another Memphis businessman, relates a similar account of his father's escape from Russia in the first decade of this century:

My father came over without my mother. He was being conscripted into the service in Russia. Of course he didn't want to go; to avoid being drafted, he poured some acid in his ear. But they were going to take him anyway, so he ran away. And he left my mother with two girls. They had sort of an underground system. He remembered swimming across the river to get to the other side. When he got over there, somebody took him in and hid him. They helped him along the way, and somehow or other he got on the ship. I guess he must have had a few dollars — enough to get on the ship. He came over here and he docked at Galveston, Texas. And there was a Jewish federation that asked him what type of work he did in Russia. Well, he used to make barrels. So they sent him over to Memphis. He got a job working at the railroad, I think, putting ties on tracks. I think he was making about two or three dollars a week. So he saved enough money in time, possibly a year or a year and a half, to enable my mother to come over here with my two sisters.

Shipboard conditions for most immigrants during that era were hardly luxurious, but the advent of relatively cheap steamship travel in the late nineteenth century made it possible for many middle- and lower-income people to come to the United States. Cattleboats and freight ships were pressed into service to carry not only Jews, but other Southern and Eastern Europeans. Fanny Scheinberg remembers that journey quite vividly:

When I was 14, Mama, my daddy, and myself left for the United States. We traveled on that boat for 11 days, from Hamburg to New York. At first we got sea-sick — me and my daddy. And my mama got so sick we thought we were going to lose her. We were in the third class. Food on the boat was meat and potatoes, and bread. Water, tea maybe, I don't remember. I think there were maybe a couple of thousand on the boat. Big boat. They had first, second, and third class. We had bunks. It wasn't soft to sleep there. We had some covers and a pillow, but not much of a mattress. My mama didn't have a samovar [a tea urn which was a common possession of many Eastern European immigrants]. We had three big packages; one weighed about 200 pounds, one about 150, and another about 100. I was able to take that and carry it on and off the train and boat. I was strong; I carried it on on [my] back.

The sea journey was often only the beginning of the troubles newcomers faced in this country. In Europe, Jews had experienced prejudice from Gentiles — in America they found it among other Jews as well. As ever-increasing waves of Eastern European immigrants poured into the U.S. the already assimilated and established Western European Jews in the Northeast began to fear anti-Semitic reactions from their Gentile neighbors. They did not want to be associated with those they considered to be lower-class, dirty, foreign-speaking Eastern European Jews. Jack Abraham, who runs Abraham's Deli in Memphis today, relates:

The German Jews, most of them came over with a little money. The Russians, Hungarians, Prussians, Austrian Jews were lucky just to get over here. It was a social separation. Even if some of the Orthodox Jews developed a lot of money, they still were not accepted. They just didn't like each other I guess. Different lifestyles. The Germans came out of clean cities, educated at good schools, and everything else. The other European Jews came out of hell-holes, ghettos — how are you going to associate with each other? There was nothing to associate, no reason.

Nonetheless, many well-to-do Western Europeans did feel an obligation to help newer Jewish immigrants. They established welfare societies and placement agencies to disperse the strange-looking newcomers to the South and West.

This planned dispersement, along with letters sent home to relatives and friends still in Europe, led many to Memphis. Some families settled in south Memphis, while others came to an area known as "Pinch," near the riverfront in north Memphis, where the first Jews in the city had lived. Evelyn Weiss says her father came to Pinch because, "He could only speak Yiddish, so he had to go where there were Jewish people that could understand."

Fagie Schaffer explains how the Jewish community helped the newcomers get started in Memphis:

When a family came over from Europe, we would call them greeners, because they were new. Some needed help. They had to become acclimated to the conditions. All of our parents were greeners at one time. They all had to come and learn the language and earn a livelihood. Most of the people that came over were peddlers. They just went to Jacob Goldsmith's and he would give them merchandise and they would peddle it in little country towns or in Memphis until they earned enough to open up a store and buy merchandise. In fact he was instrumental in giving my father-in-law his name. When he got here from Poland, he said his name was Yehetzkal. And Mr. Goldsmith said, "You can't go around with that name; we'll call you Harry I." And that became H. I. Schaffer.

Once they had acquired sufficient savings, the new immigrants brought their relatives over from Europe and set up small storefront operations such as dry goods shops, delicatessens, fish stores, kosher meat markets, and furniture shops, as well as synagogues and social institutions. In the meantime, Gilbert Delugach reports, "The German Jewish families were already moving east [where the city was expanding].' Although the Western European Jews had the financial security to help out the newcomers, they had no desire to associate with them socially; in 1916 they even moved their temple closer to their new homes and away from Pinch. Still, one person recalls that the Reform Rabbi Sanfield "was very kind to the Orthodox Jews from Eastern Europe."

Further evidence of the established Jews' desire to help out, yet remain separate, came in 1901. By the turn of the century there were so many Eastern European immigrants in Memphis that the Western European Jews founded a Neighborhood House, where these "foreigners" could go to learn how to become Americans. Fagie Schaffer, whose family ran one of the kosher meat markets, remembers this house from the 1920s and 1930s:

We had a house called the Jewish Neighborhood House. And there was a very lovely lady, Mrs. Miriam Goldbaum, a spinster, a sweet smile, most helpful and very understanding toward children. She taught us the niceties of daily living, like brushing our teeth and "this is the way we comb our hair"; we used to sing a little ditty. And she would show us the proper techniques, and, I guess, the fundamental bits of hygiene that were necessary. Taught us embroidery and crocheting and to read. The main purpose was to teach us how to be Americans so we could help our parents with English. You didn't need to speak too much English; everyone spoke Yiddish.

Yiddish (often called "Jewish") is a German dialect — with elements of Hebrew, Russian, Polish, and other languages — spoken by Jews from many countries. It thus acts as a tie among Jews from diverse backgrounds and also forms the basis of "Yiddish" culture. According to Henry Samuels, a Memphis furniture store owner, and several other members of the Jewish community, adults used Yiddish as a sort of "secret code." When Jewish storekeepers didn't want their customers or employees to understand what they were saying, they would speak Yiddish. Of course, they had to be careful. Fagie Schaffer remembers that her mother's maid "picked up all these Yiddish expressions. You couldn't speak Yiddish in front of Rosie; she knew what you were talking about. She would speak to my children a little in Yiddish."

The use of Yiddish also occurs today. Adults still sometimes speak in Yiddish or use certain words to convey a private message. Endearments, too, are expressed in this "special" language, which is also used to signal Jewish identity with the use of phrases or jokes. Today, because of the decline of the language among many second- and third-generation American Jews, Rabbi David Skopp of Baron Hirsch synagogue gives special classes in Yiddish — another demonstration of the strong current interest in reviving and preserving Jewish culture in Memphis.

Even in the early part of this century, Jews believed it necessary to preserve Yiddish culture. At the Arbeiter Ring, or Workmen's Circle, adults and children attended classes and functions for this purpose. Lewis Kramer, an active member, says:

It was a secular Jewish fraternal order. It had Yiddish schools. We had a Workmen's Circle, had all kinds of people. Some of the most religious people still belonged to the Workmen's Circle. [It] projected a better and a more just and righteous world, and they believed in that. After all, the Torah and the Yiddish law is all about justice and righteousness and brotherhood, and that's what the Workmen's Circle stood for.

Although it was called the "Workmen's Circle," this group does not seem to have been primarily a political organization in Memphis, especially in a class-conscious sense. Ben Sacharin recalls, "They weren't socialists, but it was a national organization and maybe some of them leaned toward being socialists. But no, most of the people went there, I guess, just to be with other people." (Gilbert Delugach disagrees, however; "They were socialists, although some of them later became wealthy — and ceased to be socialists afterwards.")

Rosalee Abraham remembers mostly the social rather than the political aspects of the Arbeiter Ring:

It was a real social thing; everybody would go and several mothers would cook one Sunday and several mothers some other Sunday. And they cooked a big lunch and big dinner, and they'd take the children and spend the whole day there. And they'd show movies, and play in the yard, and have a wonderful time. We'd have more fun on Sundays than doing anything else in the world. And there was lasting friendships. We were all friends for years and years. And we went on hayrides, swimming parties out on the lake. They'd get a truck and we'd all go out on a hay ride. They [also] had Yiddish theaters; they still have them once a year.

Social life, such as that provided by the Arbeiter Ring, was and is important for Memphis Jews. Besides the Workmen's Circle, several institutions still in existence provided that outlet: Hadassah, AZA, B'nai B'rith, and Masonic societies were only a few active in the first third of this century. Evelyn Weiss recalls the Menorah Institute, a one-time education wing of Baron Hirsch synagogue, with particular fondness:

I think that during those days [the Menorah] was the highlight of Memphis. Any Jewish children in the city were always welcome. It was a four-story building and on the fourth floor was a tremendous dance hall, and it was the only Jewish place large enough to accommodate such dances. The different groups would rent out the facilities and would throw a party. And there was a dance with a band every Sunday night.

There were blue laws where the Jewish people were allowed to [have social gatherings] on Sunday, but the Christians were not. Different groups would sponsor a different week, and they would be responsible for refreshments — hot dogs and drinks — and sell it and make money for their particular organization. Yom Kippur [the holiest day of the Jewish year, the day of atonement] was usually the AZA night, after Yom Kippur was over. That was the highlight. If a girl didn't have a date that night she really was just not very popular. That was the only big thing that everyone wanted to go to. Once everyone got there, it was like one big happy family.

That family atmosphere extended to the business world of the north Memphis neighborhood. After the Jewish Sabbath, (Friday sunset to Saturday sunset), when many of the stores catering to Jewish needs were closed, the area came alive for Saturday night shopping and socializing. Rosalee Abraham remembers:

Saturday nights was the night in the Pinch because all the children that were raised in the Pinch looked forward to their people coming on Saturday night to pick up their delicatessen and their meat from the butcher shops and everything. And we would all be playing hopscotch and jump rope. On Saturday nights, we got to play with some other children who came from the outlying areas, south Memphis where my husband's family came from. That was a long way from here, but he had a car and he would drive on Saturday nights and he would bring the kids.

Saturday night was not the only busy time for the shopkeepers of north Memphis. Fagie Schaffer recalls:

Most of the immigrants were really poor and they struggled to make a living. It wasn't easy for them. Only the ultra-religious, like Papa, stayed closed on Shabbos [the Sabbath]; the rest stayed open. For the merchants who kept their stores open on Sabbath, the country trade came in. And the colored folks in their wagons drawn by mules would come early in the morning, spend the day, and leave by dark.

It was through the exchange of goods and services that the Memphis black and Jewish communities most often interacted. Ben Sacharin recalls:

Oh yes, we were open on Saturday — a little on Friday. If you didn't do business on Saturday you just didn't do any business. You know, a lot of colored people would come in. They liked fish. They used to come in the wagons. Then they started coming in automobiles. They'd come in and buy maybe three or four dollars' worth of fish, cut in small pieces, which they would fry, and have little things to go along with it. And they would sell it to their own people and raise a few dollars there. We had sort of regular customers coming by.

Many of the Jewish store owners catered to this black trade, both from Memphis and from the surrounding rural areas. But the relationship between Jews and blacks was not as uniformly and mutually benevolent as some Jews remember. It also reflected the varying degrees to which Jews participated in the racism that dominated the broader community. Herschel Feibelman says:

I think they deluded themselves that blacks loved them and wanted them; they probably contributed to some suffering of blacks because they never sought to ameliorate it. They would lend money, but they would also charge more than the larger groceries would charge. They would provide some help to blacks who were unemployed or ill, but at the same time, I think that they took advantage of the whole pattern of society that was designed to keep the black where he was and give the Jew and any other person similarly situated an opportunity to advance. It's quite interesting to see how many of these [Jewish] families produced doctors, lawyers, educators, people who advanced in every avenue of life. They afforded their children lessons in music, dancing, appreciation of culture, and gave little thought whatever to the fact that this was denied the very people around whom they were living. I can 't recall a time when anyone speculated on whether or not it was a wholesome way for a community to function. If they thought about it, they quickly did something that made those thoughts go away. There was nothing they could have done about it; they did not occupy positions of influence in government; they weren't movers and shakers.

Despite the usually lopsided relationship with their black neighbors, some Jewish residents of Pinch occasionally had more reciprocal dealings with them. Oscar Makowsky relates that several black doctors lived above his father's shop:

On one side there were two black doctors and on the other side there was a black dentist. When I was a youngster, I had a toothache and I went up there and this black dentist, he did it. I didn't really think anything of it. I guess Jewish people don't really feel that way — there's only a few.

When I got here, I had never seen a black person in my life, and as I began to understand a little bit of the atmosphere of living here, I could not understand why the black people were separated from the white people, and why they were not given the same privileges to use the same facilities or eating in the same place.

Fanny Goldstein remembers an incident that gives a clue as to why tolerance did not prevail. Once, she and her mother found her grandmother in an unusual situation:

My mother and I came in one day and she was sitting down with a colored person. They were both drinking tea. My mother said to her in Jewish, "In America, you don't sit down with people that work for you, people that were beneath you or whatever." And my grandmother said, "This person is sending two children through school and do you think anybody is better than a person that makes such and such and sends two children through school?"

Not all Jews regarded blacks merely as servants, but many Memphis Jews did rely on black maids to run their households. Since these first generation families rarely had large extended families to help with domestic duties, many chose to hire a maid to enable both husband and wife to work outside the home. Wives worked alongside their husbands, many present-day Memphis Jews remember. Fanny Goldstein recalls, "I always said I never saw my mother sleeping, because she worked in the store all day and she baked all night. She ran the store and she was a very aggressive and hard-working woman, my mother." Oscar Makowsky remembers: "My mother, she was very aggressive in business, smart as a whip. She was a mover. She got things done. She wasn't much as far as a housekeeper. She really belonged to the women's rights movement."

Along with involvement in the business world, a Jewish woman usually retained her traditional role as cook; keeping kosher (observing Jewish dietary laws) was considered too important a matter to surrender to non-Jews. Yet Southern customs would occasionally creep into Jewish homes, even in this key area of Jewish culture. Such changes were often due to the influence of the black domestic workers. Fagie Schaffer remembers her maid

would make greens for my kids — couldn't use bacon stock but she would substitute because I didn't know how. She would use brisket or a little schmaltz [chicken fat]. She taught me how to fix good green beans. What I do is take a little oil and put it into my water with salt and pepper, and a little onion and cook it down. Many a dish she showed [me].

Joe and Mildred Krasner explain how their family reacted to Southern food:

You know, the Jewish people were raised different than the gentile people. They were all with the grits and the greens and all that, whereas the Jewish families — we keep with the Jewish way of eating — the way they learned in the old country. Meat and potatoes was the main dish. We'd never heard of salad until we came to Memphis. We never had salad. I can remember my mother putting a salad in front of my father and he said, "What am I, a cow?"

Despite the fact that pork is not kosher, eating pork barbecue is another Southern food tradition that some Memphis Jews have acquired. Jack Abraham, whose family once ran a meat-packing plant, says that as a teenager — although his family would have no pork in the house — he went out to local cafes and ate it there:

Whenever we went out [for a date], we'd never go home without going by the "Pig and Whistle." I don't remember the old people going there; I was young. You had to go by the "Pig and Whistle" or the "Jungle Garden" and let the people see you. My parents knew I was going to the "Pig and Whistle"; they didn't know I was eating barbecue. I'd tell them I had an order of french-fried potatoes, forget to mention the barbecue.

This exchange of Southern and Jewish foodways also worked in reverse. Evelyn Weiss remembers that her mother's maid "would take all these kosher recipes like strudel and gefilte fish to her church, and they loved it."

White Southerners were also affected on occasion. One rule of keeping kosher is the strict separation of meat and milk products. Fannie Goldstein relates an incident that occurred during the Depression in her grandmother's delicatessen:

The NRA [a New Deal relief agency] gave you stamps to buy things and they gave you directions about a lot of things. We were a strictly kosher business and a man came in — a non-Jewish man — and he ordered a corned beef sandwich. When the waitress brought it to him, he wanted a glass of milk, and she said to him, "I'm sorry, we're not allowed to serve milk with the corned beef sandwich." And he got up and slammed his napkin down and said, "Damn the NRA! Now they're going to tell me what I can eat!"

Jewish and African-American traditions were not the only cultures that mixed in the areas of Memphis where Eastern European Jews settled. The Memphis city directories show that Germans, Irish, Greeks, and Italians also lived in Pinch during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, although their numbers decreased as time went on. Mildred Krasner recalls:

We had Italians, and we had Greeks. The Italians had a grocery store across the street from our store — two or three Italian families lived in our area. We got along fine; in fact, we are still friends with the families that lived along there. We see them, we talk to them, we're still friends. We never did fight or have any fights with the kids.

Fagie Schaffer also remembers little animosity among the children of differing ethnic backgrounds who lived in the neighborhood:

We all played together, [but] mostly the boys — the Greeks, Italians, and Jews. There is a story, one of the old-timers was looking for a minyan [10 males over the age of 13 necessary for a service] in the park. He rounded up a bunch of boys from the park and it was one or two Greeks and he didn't know the difference. He just put a yarmulke [skull cap] on him and let him be part of the minyan.

And according to Fanny Goldstein: "I never remember as a child ever having any kind of phrases slung at me that might make me feel inferior as in 'Jew.' I don't even remember hearing an Italian being called a 'Wop' or anything derogatory toward the Irish people. I think we assimilated beautifully."

But assimilation only went so far; as Fagie Schaffer remembers "a Jewish girl did not date a gentile. It just wasn't done."

Yet Mrs. Schaffer also recalls:

My mother sent me to the Catholic convent to learn to play the piano. At this time it strikes me as odd; at that time I didn't pay any attention to it. I would go into this Catholic convent and receive my instructions from Sister Sophina, who used to rap my knuckles with a long knitting needle if I struck a wrong note. And I recall that during Passover she would give me a big Easter egg and I could never bring it in the house or eat it because it was always at the time of Passover. But she did not corrupt us or give us any of her religious background. She taught me music and that was all.

Despite such evidence of friendly relations between ethnic groups, it was not always easy being a Southern Jew. According to Herschel Feibelman, many were isolated and forced to deal with attitudes foreign to their own. The Jew in the South, says Feibelman,

had to adjust himself quickly to Southern attitudes. He might find differences between prophetic ideal and community practice as regards blacks, but he had to be very careful and make sure that he accepted the mores of that community or that milieu. No one, certainly not a Jewish merchant, wanted to be called a "nigger lover, " which is an odious expression, but which of course would mean that he was more inclined to favor blacks than someone else who lived in the community.

I think the Southern Jew had one other condition which affected his acceptance, and it is not a happy one to discuss, but it existed and exists to some extent right now. The Jew was isolated from the lowest level of community acceptance, because that dubious distinction was reserved for the black. In a stratified society, there was always someone to be below the Jew. In the Northern community, there was a succession of immigrants who suffered this. In Boston it was the Irish. In New York, first the Irish, then the Jews, then the Italians — now the Puerto Ricans perhaps — and then the blacks. So the Southern Jew, very quickly, within one generation, perhaps within in decade or two, began to feel like he belonged.

The feeling of belonging was not always present. Although many Memphis Jews claim to have been unaware of its existence when they were growing up, anti-Semitism did flourish in certain areas of the South. In the early twentieth century, Atlanta was seen as a focal point of anti-Semitism because of the case of Leo Frank. Frank, a Jewish businessman, was convicted in 1913 of the rape murder of a 14-year-old girl. Two years later Georgia Governor John Slaton commuted the death sentence to life imprisonment (Frank's innocence has since been established), but vigilantes stormed the prison and lynched Frank. The incident gave rise to a resurgence of the Ku Klux Klan and the first KKK crossburning, which occurred at Stone Mountain. In addition, B'nai B'rith, a Jewish fraternal organization founded in 1843, established the Anti-Defamation League ("to work for equality of opportunity for all Americans in our time") in reaction to the wave of anti-Semitic incidents that occurred throughout the South as a result of the Frank case.

Lewis Kramer recalls:

It happened in the year I was born, in 1915. The Jews of Atlanta were terrorized and boycotted and my folks had a store in the neighborhood where Mary Phagan lived, the girl that was killed, and they were boycotted because they were accused of giving $500 to Leo Frank's defense fund. It was the only lynching of a Jew in the United States. And such a crime and such injustice that was brought to a man that was innocent. The governor was almost lynched himself because he commuted his sentence from death to life so he could gather more evidence because he was not satisfied with the evidence that was presented at the trial.

When I first got married and we were going to a place called Stone Mountain to a wiener roast, there was a Ku Klux Klan demonstration with all the white hoods [men] and sitting on the fenders of their cars. And it scared my wife and she hid under the dashboard. And I told her if you 're going to live in Atlanta, you might as well get used to this, because it's an everyday occurrence. We don't pay no attention to it.

Such blatant anti-Semitism was not evident in Memphis, but one local newspaper, The Commercial Appeal, did print the following item from an Atlanta paper on June 3, 1915, in the midst of the Frank trial:

It was soon evident [once the trial began] that the Atlanta Jews were making a race issue of the matter as they rallied about Frank with unanimity, and the trial had not proceeded far before one of Frank's attorneys injected the race question by declaring Frank was being persecuted because he was a Jew. . . . Thousands of Georgians think that whatever prejudice marks the Frank case has been caused by the manner in which his co-religionists in Atlanta and elsewhere rallied to him.

Interestingly, during the same time that the Leo Frank case was being widely reported, the paper also carried reports of blacks being lynched nearly every day. The Commercial Appeal's, coverage emphasized the illegal nature of the lynching of Leo Frank, condemned anyone who favored it, and conveyed horror at the mob's action. No regret for the lynching of black people was expressed, however.

Some anti-Semitism, regardless of the reactions to the Frank case, did exist in Memphis. Henry Samuels recalls:

Sometimes in business, when you were waiting on a customer, a lot of country people [mostly blacks] come in. You would be making a sale and of course on North Main Street then, out of say nine furniture stores, say five of them were owned by Jewish people. And you'd be writing up a sale — "I'm sure glad I came back to you, because I almost bought it from that Jew store up the street. " I had red hair — they didn't think I was Jewish. That's when you had to keep quiet and take their money and tell them good-bye, you know.

Fagie Schaffer remembers that once "Papa was walking home from the store late one night and some little boys jumped him. He wore a beard and there was some name-calling. They threw stones at him, but these were little colored boys that did that, around the wartime in the early 1940s."

Anti-Semitic incidents were us ually isolated. Many Jews were prominent in the Memphis business community and few Gentiles were likely to risk public disclosures of anti-Semitism, which was not as socially acceptable as antiblack sentiment. Certainly the Klan does not embrace Judaism or Jews, but neither are its anti-Semitic activities anything like the Russian pogroms, which Jews fled in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, or the Holocaust. Most Jews living in Memphis today do indeed feel that they belong there. Being Southern has become a major part of their lives. Fanny Scheinberg remembers:

When I first came here, I wanted to go back [to New York], but after I was married and I had my children here, my friends in New York came to visit. They said, "Oh, Fanny, I'll bet if you had the chance you'd like to come back." And I said, "You couldn't give me New York on a silver platter!"

And according to Lewis Kramer: "I think we are more hospitable [down here], more warm, more close. [In the North] everybody is cold and curt, just for theirself. I wouldn't say everybody, but a great percentage of the people."

For the most part, the Jews who live in Memphis consider themselves as Southern as their Gentile neighbors, but they also regard their community as being as Jewish as any in the Northeast. Race relations, the nation of Israel, intermarriage, and the fear of anti-Semitism are on-going concerns in Memphis — as they are for most American Jews. Support for Israel is mixed, but at the same time, Jewish identity is being exhibited more and more in Memphis today. The existence of Jewish meat markets, kosher bakeries, and even a ritual bath testify to the endurance of these centuries-old traditions, which have been strengthened through continuing contact with Jewish communities in other cities, as well as through national Jewish organizations.

Life in the Southern U.S. has been far from perfect, yet it has fulfilled the dreams of many Jewish immigrants and their children. Says Oscar Makowsky, "I know I've said this before, but the youngsters that grew up in that area, a lot of them became very famous people. What I mean famous, I mean professionally. A lot of them became attorneys, doctors, and Ph.D.'s." They and their families have achieved material success, but, more importantly, they have found religious and social freedoms incompatible to anything they knew in Europe. And their ambition has been to pass on a deep regard for these liberties to their children. As Oscar Makowsky says, "In Judaism the priority is the teaching of the children. You've got to teach the children. That's the only way Judaism can exist," in the South or anywhere else.

Tags

Rachelle Saltzman

Rachelle Saltzman was director of an Ethnic Heritage Project at the Center for Southern Folklore in Memphis, Tennessee. All interviews cited here were completed as a part of this project during 1982 and are the property of the Center for Southern Folklore. The research for this article was made possible by grants from the Department of Education, Title IX, the Ethnic Heritage Studies Project; the Hohenberg Foundation; and the National Council of Jewish Women, Memphis section. (1983)