Co-Ops/Hilton Head Island Fishing Co-Op

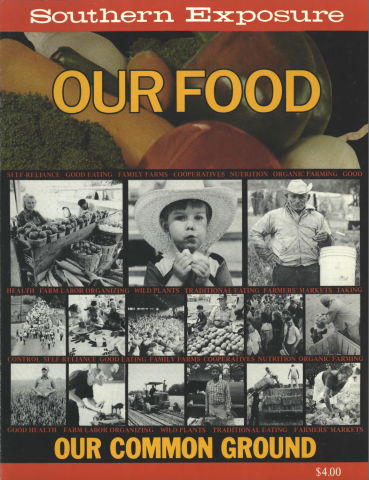

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 6, "Our Food." Find more from that issue here.

Catching food from the sea has always been integral to black life on Hilton Head Island, South Carolina. After the Civil War, blacks sought self-sufficiency through crabbing, shrimping, fishing, oystering, and farming, taking their catch and produce to the Savannah docks by sailboat to be sold.

Today that life is largely a thing of the past; most residents depend on the resort industry for their livelihood and fish only for personal consumption. But one group of black islanders continues the tradition of shrimping and, since 1968, has eked out a living by pooling resources in the Hilton Head Island Fishing Cooperative. The shrimpers’ success has ebbed and flowed with their catch, and there are many stories to be told and lessons to be learned from their experiences.

Thinking it was time for black shrimpers to own a dock of their own, Hilton Head native Freddie Chisolm initiated the call for the co-op in the mid-’60s. The black shrimpers faced discrimination in unloading and selling their catch at the existing docks and had the lowest purchasing priority for the fuel and ice essential to their trade. As often as not they were barred from repairs of their boats and nets on the white-owned docks. And, most importantly, the market price they were offered for their shrimp was lower than what the white shrimpers got.

Chisolm called together a group of 12 men who shared these grievances against white dock owners. Although not all were boat owners, all committed themselves to developing a black-owned and -operated enterprise that would get them a fair price for their shrimp as well as provide the means for maintaining their trawlers.

After almost a year of meeting BY VERNIE SINGLETON together to discuss how best to go about starting the co-op, each member agreed to contribute $500 and 15 percent of his catch. They used this pool of money to pay for docking space, net repairs, fuel, and ice. One of their number had some experience with fund-raising, and under his guidance they wrote proposals and grant applications. An Office of Economic Opportunity feasibility study led to a loan from the Farmers Home Administration for $66,290. Other money came from the Ford Foundation and the Lutheran Church.

With this seed money, the group opened up a fishing cooperative along Pope Road on the north shore of the island. Relying solely on shrimp, the co-op was quite successful in the early years when shrimp were plentiful. Membership grew to 16, and in 1975 20 boats were regularly serviced at the co-op’s dock, some of which belonged to non-members who docked with co-op permission. Relations between black and white shrimpers improved, and some white shrimpers regularly unloaded at the co-op dock.

In the early ’70s the co-op attracted a lot of attention — not for its shrimping success, but for its strong stand on an environmental issue. Local estuaries were threatened by the plans of BASF, a German-owned chemical corporation, to locate a plant at Victoria Bluff not far from Hilton Head. The shrimpers gathered 45,000 signatures protesting the plan and took the Captain Dave, a local trawler, to Washington to hand-deliver the petition to the Secretary of the Interior. This act was crucial in keeping the plant out of the area, and the publicity brought people from as far away as China to learn about the co-op and how it worked.

But this success did not help the co-op resolve its most pressing problems: undercapitalization and the need for better management.

“We had some bad years,” says David Jones, who was the co-op’s founding president. “For about three years there weren’t any shrimp to catch.” Jones had to sell one of his boats in 1977 and the other in 1979, when shrimp were too scarce and the cost of fuel too high for him to continue shrimping. The best year was 1976 when the co-op’s 234,795 pounds of shrimp sold for $481,247. The worst year, by contrast, was 1981, when the catch dropped to 51,615 pounds, which sold for $160,011. The catch was up again in 1982 — to 91,090 pounds — but the bad years predominated. Poor record-keeping and some misuse of funds meant the co-op lost money in the bad years. Members sometimes defaulted on their loans from the co-op, and the business went in debt for supplies shrimpers bought but failed to pay for on schedule.

Today the co-op still owns the facilities, but the members have relinquished control over managerial decisions and operations by leasing them to a former co-op vice president. Even if survival is not in the cards, though, the Hilton Head co-op served its members well for a time — and served also as a subject for study and an inspiration to other cooperative ventures at home and abroad.

Former president Jones blames members’ lack of management skills for the failure to cope with the hardships of bad years. But he also says: “It depends on working together. That’s the co-op as a whole — working together. When we first started out, we were working very close together. As the years went on we started getting this division among the members. When you start getting those divisions you began to get bad attitudes. Then the business began to fail. So that’s why I say work hard and work together.”

Tags

Vernie Singleton

Vernie Singleton is a free-lance writer and a native of Hilton Head Island. (1983)