This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 11 No. 6, "Our Food." Find more from that issue here.

The oranges are tree-ripened. They haven’t been primed by chemical fertilizers or protected by pesticides. Without dye to brighten them or wax to polish them, they don’t look like “TV oranges.” Because of their mottled appearance, the Florida Citrus Commission says they aren’t U.S. No. 1 Grade and can’t be sold in supermarkets. But to the chemically sensitive, these oranges are essential. To those who have tasted them, they’re delicious. To those who grow them, they are the tangible product of a philosophy that has at its heart a concern for the land and people.

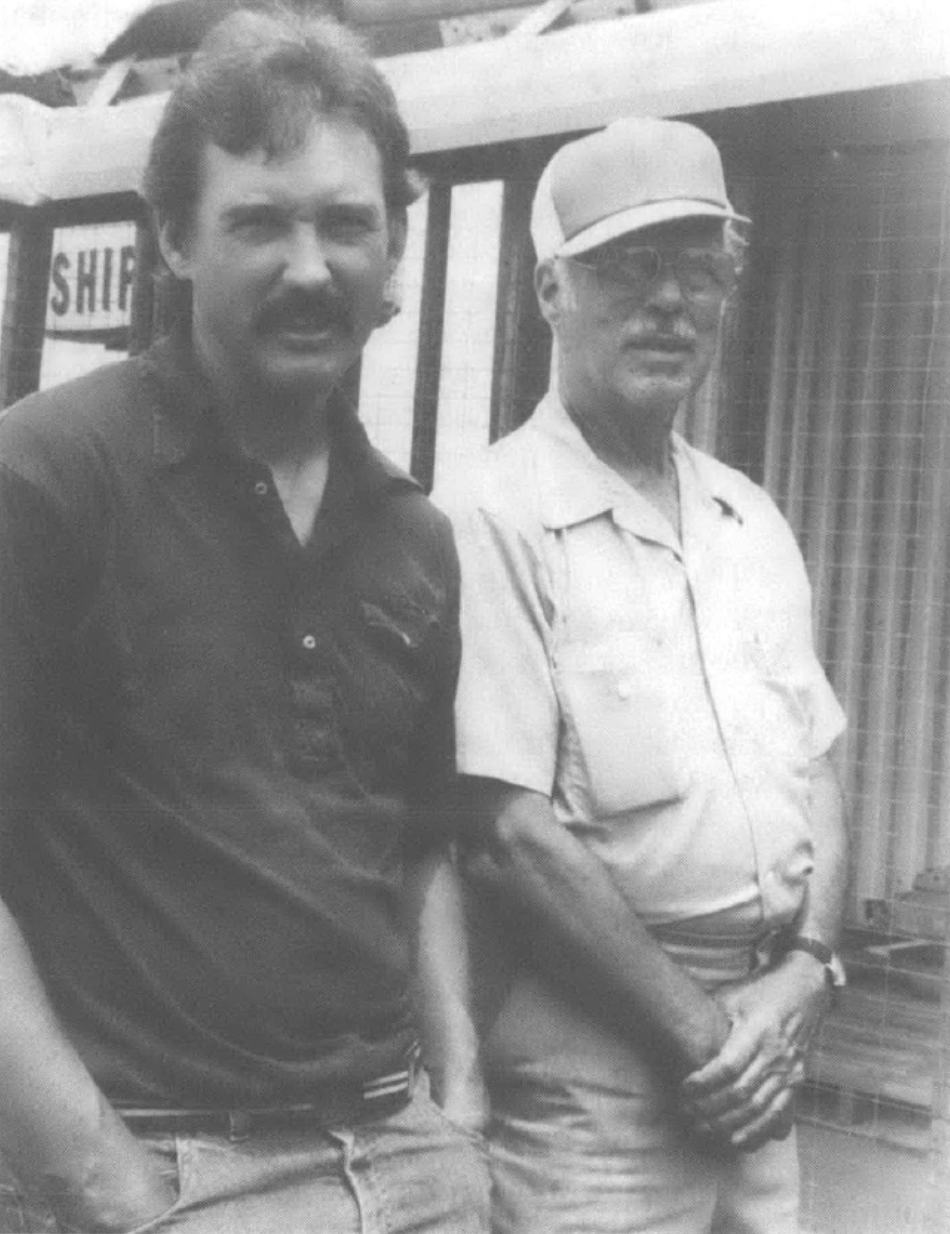

Lee and Virginia McComb are among the pioneers of organic citrus. They haven’t g revolutionized the citrus in- a? dustry, but they are proud of their work. Owners of 65 ^ acres of orange and grapefruit groves around Leesburg, Florida, they have survived three decades as growers, built up a compostmanufacturing plant, won a few battles with the Citrus Commission, and welcomed their son David into the business. Their experiment seems to be working.

“Growing food is just a means to an end — people are the end,” Lee McComb says. At 76, he is a tall, tanned man who is eager to discuss why he is committed to ecologically sensitive farming. “If you have a concern for people — for their health,” he says, “you’re going to have to have a concern for everything all the way up the line, from the soil up.” In agricultural terms, Lee’s concern translates into a program that involves applying compost and natural controls to his groves. He is quick to say he has nothing against chemicals in themselves: “The problem is that chemical fertilizers are so highly concentrated with so few elements — usually only nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium — that they upset the balance of the soil. Over the years they deplete the natural nutrients in the ground.”

His experience as an assistant production manager of a large Pennsylvania farm convinced him that chemical fertilizers gradually destroy the very soil they are “enriching.” “I saw we were making sick soil that made sick plants that attracted insects and disease,” he says. “If we were doing that to the plants, what were we doing to the people and animals that ate those plants? I figured there had to be a better way to farm.”

Looking for a better way, Lee and Virginia left Pennsylvania and moved to Florida in 1945 to start a composting business. Although they were received with less than wild enthusiasm by the local Leesburg farmers — especially since at the time there were no machines designed for spreading compost — the McCombs stuck with their business.

By the early ’50s, Lee says, “I had bought a 10-acre orange grove and I was ready to try my compost and my methods on my own land. Trouble was the grove I bought was dying. An average grove in Florida is on the way out by the time it’s 25 to 30 years old. If the soil wasn’t leached of its nutrients year after year, the trees could last four times longer. Anyway, I started my program on this dying grove: no pesticides, no chemical fertilizers, no clean cultivation.”

Thirty years later, Lee walks the dirt road beside that same grove, proudly showing me the tall, healthy trees. “They’re still producing,” he says, pointing to the green fruit shining in the July sun. According to his 31-year-old son David, the groves not only produce, they produce well. On the average, the McCombs harvest 400 boxes per acre — at the upper end of the state average of 350 to 400 boxes per acre.

As a second-generation citrus grower, David echoes the concerns of his father. “We concentrate on growing from the soil up,” he says. “I call it ‘inoculating the soil.’ The fact that my soil’s alive gives the trees more potential to pick up nutrients and ward off disease. I’d rather have the soil good so I won’t have to spray the leaves.”

In growing their citrus, the McCombs try to understand and work with the natural environment. Virginia, a pleasant, white-haired woman who gives an impression of quiet competence, explains how terrain may determine if orange trees suffer damage in a winter freeze. “If there’s a hill in the grove,” she says, “cold air will move down into a pocket and the trees higher up will be saved. That’s called ‘air drainage’ and you need to look for that when you’re buying a grove.” Lakes, also, according to Virginia, are natural protection against freezes since cold air is warmed as it passes over water.

When Lee takes me on a tour of his groves, I see how even weeds are granted a place in the McCombs’s respect for nature. An exotic tangle of undergrowth shoots up high and thick around the orange trees. It seems a tempting haven for rattlesnakes and I wonder aloud how the pickers feel about venturing into such a thicket. Lee assures me that the weeds are plowed under in the fall before the harvest; he doesn’t plow regularly like most growers, who, says Lee, “are afraid of weeds.” He believes the weeds act as a living mulch, keeping moisture and nutrients in the ground. The citrus trees themselves are thriving, full of fruit.

A range of problems — from the humorous to the serious — has come up over the years. Lee smiles as he recounts how he once decided to go into the snail business. A natural friend of orange trees, snails work like tiny vacuum cleaners moving slowly over the leaves cleaning them. Lee invested $600 in enough snails to start colonies on his trees. Visions of a snail empire were crushed, however, when raccoons raided the sacks he kept the snails in during cold spells.

What about other problems? “I haven’t had problems, I’ve had challenges,” says Lee. “One of the challenges has been the Florida Citrus Commission. They didn’t take us seriously at first. They thought it was a joke and that we would fold in a year or two.” When the McCombs persisted in growing fruit without chemicals or sprays, the commission prohibited fruit from being shipped out of Florida that wasn’t U.S. No. 1 Grade.

“That means how pretty it looks, not how good it is,” according to Lee. The regulation prevented the McCombs from selling their citrus anywhere but juice plants and roadside stands. Eventually, after a vigorous letter-writing campaign waged by the McCombs and their customers, the commission modified the rule to allow “organic citrus” to be shipped out-of-state. The McCombs are now limited mainly to what is called the “gift-fruit” market — mail-order home deliveries — and to wholesalers who supply health food stores and cooperatives.

Without the U.S. No. 1 Grade, the McComb fruit is excluded from one of the largest parts of the commercial market - the chain grocery stores. Lee speaks long and passionately about the need to open up that market for organically grown food. “We have got to give up the idea of basing food grade on cosmetics,” he says. “We shouldn’t buy food for prettiness, but for nutrition and taste. We need to re-educate the public.” Active members of the Carolina Farm Stewardship Association, the McCombs are part of a network of Southern farmers who are working together to promote the methods and markets for "healthful, sustainable agriculture.'

While David firmly supports his father’s approach to farming, he is skeptical about trying to re-educate the public on food issues. “It’s their business what they eat,” he says. “They have to make their own decisions.” He speculates that 20 or 30 years from now, people will have made the connection between how food is grown and the health effects — either because of scientific evidence or because they have figured it out for themselves. Until then, David believes there is no reason not to try to produce what people want — “as long as you don’t sacrifice the integrity of the fruit.”

The criteria by which the McCombs measure the “integrity” of their oranges and grapefruit is by no means absolute and complete. Put simply, they want to produce “the best food” they can. A test analysis Lee has commissioned indicates that his citrus contains significantly less acid and more vitamin C and minerals than the same variety of oranges grown on chemical fertilizers. For chemically sensitive people who cannot eat most commercial citrus, the McCombs’ fruit fulfills a vital requirement. “I think we produce as nutritious a piece of fruit as we can,” David says, “but I think we can do better.”

The future poses many agricultural and economic challenges for the McCombs. Not only are they still excluded from chain grocery stores, but another of the largest markets for citrus — the frozen juice companies — is really just a last resort for the McCombs. “Our goal is to get the most nutritious fruit into the individual stomach and not the juice can,” David says. When it is mixed with chemically grown oranges and boiled down into concentrate, the value of organic citrus is largely lost. To offset these commercial limitations, David hopes to expand their groves to include popular varieties like navels and red grapefruit. “Basically,” he says, “this business means keeping your heart right, but being logical with your pocketbook.”

Through all their years of planning and work, the McComb family has shown a remarkable knack for combining good intentions with practical results. Their success is encouragement for all those who would like to see a flourishing agriculture that has at its core a concern for the land and people.

Tags

Cheryl Hiers

Cheryl Hiers is a writer who lives in Ormond Beach, Florida. (1983)

Born in North Carolina and raised in Florida, Cheryl Hiers is currently doing graduate work in English at Vanderbilt University. “A Citizen of Florida” is the title story of the collection which forms her master’s thesis. (1981)