This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 1, "Elections: Grassroots Strategies for Change." Find more from that issue here.

All over the country, low-income people generally, and people of color in particular, are being accosted by the advocates of the New Movement Strategy. We are organized on the food stamp lines, agitated as we try to get our unemployment checks, and hustled as we trek down to the welfare department to try to qualify for emergency assistance and processed cheese. The strategy? Assault the White House? Rip off the big chain supermarket? Eat the rich? No — register to vote!

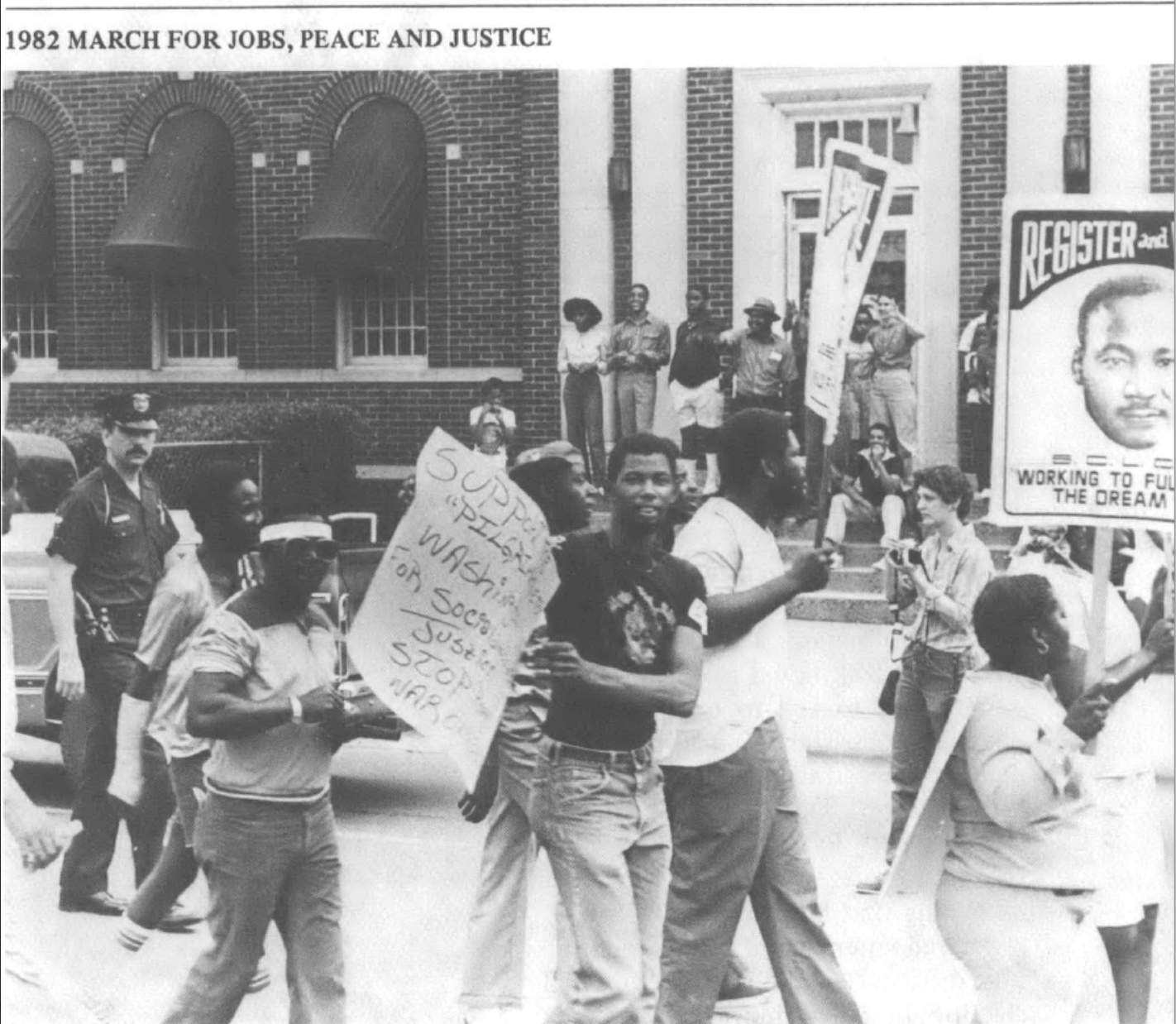

Noting that huge numbers of unregistered voters could make a significant difference in the 1984 presidential election, literally hundreds of student groups and community organizations, as well as the whole welfare establishment, have taken up the banner of voter registration as a major progressive counterthrust to the New Right's control over federal and state government.

The notion of registering voters to ensure accountability from the state is not new. Many groups, including the Voter Education Project, the Urban League, NAACP, Southwest Voter Registration and Education Project, and League of United Latin American Citizens, to name a few, have been registering thousands of voters for years. The most consistent advocate of this tactic in the black community was Bayard Rustin, whose 1964 article "From Protest to Politics" argued that the primary strategy for consolidating the gains of the Civil Rights Movement was through the election of black candidates. Voter registration became a major thrust in the political organizing which elected black mayors in Gary, Newark, Detroit, New Orleans, Atlanta, and Los Angeles. Similarly, the Latino community, particularly in the Southwest, has been registering voters and pressing for the bilingual ballot.

So why the big splash in 1983 over voter registration?

First, the Right has done what no progressive organization or charismatic leader of the Left has been able to do: provide a unifying focus. The massive redistribution (read cutbacks) of the budget from human needs to the military, failure to initiate a jobs program, intervention in Latin America, continued support for repressive regimes around the world, and the escalated possibility of nuclear war have forged a broad-based constituency whose common aim is to oust Reagan.

Massive voter registration as a progressive strategy received intellectual and political legitimacy from another quarter when scholar-activists Frances Fox Piven and Richard Cloward published a key article in Social Policy entitled "Toward a Class Based Realignment of American Politics: A Movement Strategy." Bolstered by the Piven and Cloward analysis, voter registration has become not simply "a way to get Reagan," but a politically correct action as well. The Piven and Cloward strategy, which relies on student and social welfare agency employees as voter registrars, demonstrates that the left/liberal infrastructure can be mobilized, and that low-income people of color will, in fact, register.

So what could be wrong with a voter registration campaign focusing on low-income third world people?

First, there is the question of options — for whom or what will people be able to vote? A choice between Mondale and Glenn is not particularly exciting. Nor do these candidates represent political positions that are in concert with the interest of low-income people of color. On the contrary, it could be argued that Mondale and Glenn represent corporate interests that demand increased tax breaks, lower labor costs, and decreased regulation of plant mobility, occupational health and safety, and environmental safety. Both, in general, support American economic and military international interventions.

Then there is the question of realignment. In looking at the rule changes within the Democratic Party, it appears that the party has already been realigned — toward the party regulars. While the Democratic Party opposed Reagan on some issues, there has been no significant Democratic opposition to workfare or Simpson-Mazzoli or subminimum wage. So as we embrace the "strategic opportunity" afforded us by our friends in the Democratic Party, we ought not to be surprised if they act like they knew we had no place else to go and they don't have to make us any concessions.

If there are concessions, who'll cut the deal for low-income people of color? Aside from the Democratic Party heavies, the most likely person to be in a position to cut deals will be Jesse Jackson. Yet no other aspect of the issue of running a black presidential candidate has caused such an uproar and split in the black leadership as the prospect of Jesse Jackson as that candidate.

Voter registration experts note that Jackson's candidacy will spur black voter registration and that the support generated for Jackson's candidacy will certainly give him some deal-making ability after the primaries. But questions arise concerning whom and what Jackson represents. As a recent article in The New Republic points out, "[Although] praised for his dynamics and his electricity, Jackson is chided for being arrogant, shallow and a one-man show whose programs are long on style and short on content and execution. Jackson is no revolutionary; he seldom takes a position that might alienate his supporters. His beliefs are still basically Baptist and fundamentalist, including his (now muted) anti-abortion stand." So the question remains whether registering to vote gives low-income people of color any real choice.

While it is true that registering low-income people to vote may be an important tactic in pressuring the Democratic Party (the spigots of social spending will definitely open wider), it is without question not a strategy for party realignment, let alone for fundamental change.

In order to move a disfranchised low-income constituency into a position where we can effectively manipulate the state, it is necessary to demonstrate electoral clout. Voter registration alone, however, does not constitute a strategy, for a strategy would include a process of organization to develop grassroots analysis and action on issues; a tactical repertoire of direct action as well as electoral activity; and the development of an alternative social and economic program, so that, regardless of the personalities involved, we could understand not only what we are against, but also what we are for.

While voter registration does have tactical importance, it is clear that the current campaign may not reach the strategic level of projected political significance unless political education, direct action, and policy development become an integral part of the organizing.

Tags

Gary Delgado

Gary Delgado is the Director of the Applied Research Center in Oakland, California. (1996)

Gary Delgado is director of the Center for Third World Organizing. This article is reprinted from Third Force, the newsletter of the Center for Third World Organizing. (1984)