This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 1, "Elections: Grassroots Strategies for Change." Find more from that issue here.

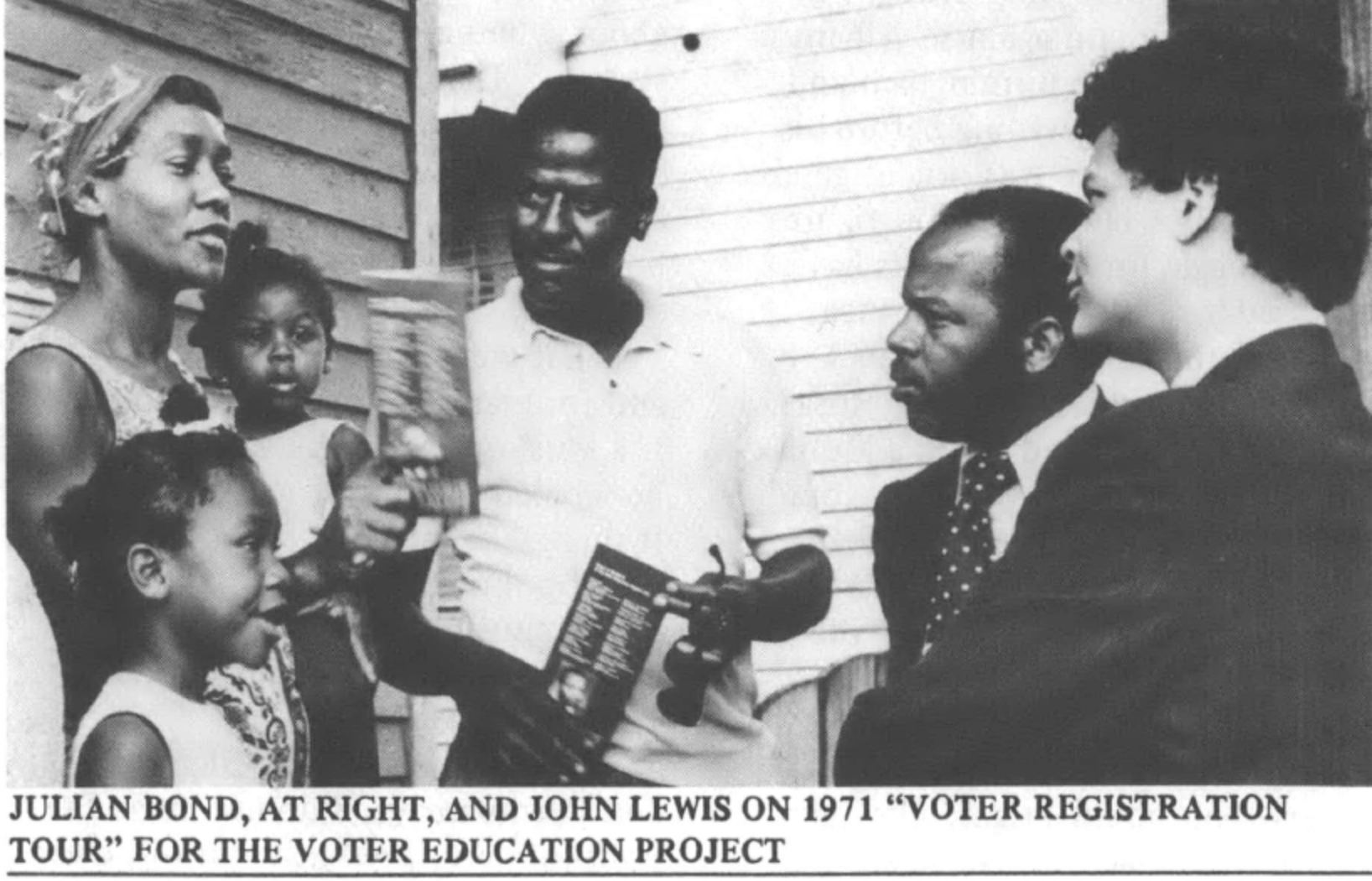

Georgia state senator Julian Bond is president of the Institute for Southern Studies, which publishes Southern Exposure. Copyright © 1984 by Julian Bond

If you ever wondered what difference it makes who sits in the White House or whether electoral politics matters in your life, consider the sweeping consequences of Ronald Reagan's narrow victory in 1980 For three years, we've lived under an administration run by the amiable architect of avarice as social policy.

Over 8 percent of the nation remains unemployed. The unemployment rate for black adults is 20 percent, and for black teens it is over 50 percent.

Fifty-seven cents of every federal tax dollar are committed to military-related expenses.

Our government opposes abortion, and supports the death penalty — apparently believing life begins at conception and ends at birth.

They intend to rearrange America to fit their sterile vision, to force conformity with their small minds and smaller dreams. Riding the crest of a wave of antagonism against those Americans who cannot do for themselves, they intend to impose an awful austerity on us all.

At home — and abroad — they have surrendered the general good to the corporate will. They intend to radically alter the relationship between America and Africa, to substitute mineral rights for human rights, and they continue to embrace and endorse South Africa, the most horrific government on the face of the planet earth. America's position as the richest society on the planet too often identifies us with an old order that is passive and against a new order struggling to be born.

For the first time since the Nixon years, the actions of the Justice Department are subject to the review and approval of the White House, and to political intervention from powerful Republican politicians.

For example:

• The Justice Department — at the request of Alabama Senator Jeremiah Denton — removed the term "White Supremacy" from a suit against white supremacy in Mobile, Alabama.

• After House Republican Whip, Trent Lott of Mississippi, objected to a suit against jail conditions in his state, the attorney general's office announced that no longer would the Justice Department bring such suits.

• At the insistence of Senator Jesse Helms, the Justice Department agreed to an integration plan for North Carolina's public colleges that violated the standards set by the Department of Education.

• In school integration cases in Seattle, Nashville, and Chicago, the Reagan Justice Department reversed the position taken by its predecessors, and supported school desegregation plans that would reinforce segregated schools.

• The assistant attorney general has restricted enforcement of federally-mandated plans for equal employment opportunity, and has retracted the requirement that federal agencies obey federal law, in hiring and promotions.

As the destruction of civil rights has moved forward, the greedy appetite of the military machine grows more voracious every day. This administration is beating our plowshares into swords and our pruning hooks into spears. The choice they put before us is greater than guns versus butter; it is soup kitchens and surplus cheese versus expensive airplanes and malfunctioning tanks.

On October 28, 1980, candidate Reagan asked the voters of America to ask themselves if they were better off than they had been four years before when Jimmy Carter was elected president of the United States.

After three years of the Reagan presidency, that question must be asked again.

If you earn more than $100,000 a year, the answer must be yes. You'll haul in an extra $2,000 a year from the Reagan tax give-away, and even at that level, $2,000 can't hurt.

If you dump poisonous wastes in a river or a lake, it's smooth sailing ahead; the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has cut back its enforcement forces.

If you manufacture products that could be dangerous to the public, you're in good shape. The Consumer Products Safety Commission has dropped investigations of products linked to 60,000 injuries and 500 deaths each year.

If you own a factory that's dangerous to your employees, you're home free. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) inspections were down 17 percent in 1982.

A new kind of social Darwinism has been foisted upon us — the survival of the richest.

Despite the oppressive forces around us, despite the heavy weight of the self-satisfied, the cold-heartedness of the neo-conservative confederacy, a great deal of the solution to our current condition lies within our hands.

The power of the ballot box is an undeveloped resource in much of America.

Only 61 percent of eligible blacks were registered on November 4, 1980.

Only 55 percent of them had the energy and initiative to actually vote.

Only one-third of those blacks between 18 and 25 were registered to vote.

Almost nowhere do black and white Americans vote in equal percentages of their registered populations.

Almost nowhere do progressive voters specify the demands we make on those who represent us. Almost nowhere do Americans of different races work in effective coalition.

Almost nowhere are we able to punish enemies as easily as we reward friends.

We seem to have forgotten a message Martin Luther King brought us in Montgomery and again in Albany, and in Selma and in Birmingham and in Memphis on the evening before his death. That message was not original with King, but few leadership figures in the struggle for human rights have expressed it so well before or since.

In our times, it began when a department store seamstress, Rosa Parks, refused to stand up on a Montgomery city bus so a white man could sit down. Until that day in 1955, most black Americans were little more than eager bystanders at the side of the stage upon which was acted their liberation.

The actors were those few black lawyers who could litigate the race problem, or black social scientists who could codify and chart and graph the dimensions of the terror of racial injustice. The average men and women who were black found their participation limited to voting — where blacks were permitted to vote — or to making a meager contribution in cash or kind to the works of that small band of civil rights professionals.

But when Rosa Parks refused to stand up, and when Martin King stood up to preach, mass participation came to the movement for civil rights.

For nearly 20 years, a progressive national movement, fueled by the fire from the Southern civil rights struggle and the national anti-war drive, armed by legions of youth from college campuses and corner pool halls, grew and prospered in the United States.

That movement passed two successive civil rights bills guaranteeing black Americans the right to public accommodations and the precious right to vote. Its lobbies and marches convinced 50 percent of the American population that the war in Vietnam was wrong, and that American adventurism ought to be abandoned. It nearly won important reforms in the nation's oldest political party. It aided — often unwillingly — the rebirth of the movement for equality for women. It saw a concern grow for the quality of our air and water. It set college campuses aflame, and indirectly, raised public anger to set some cities on fire, too.

What is required now is a recreation of the vision and drive that wrote the 1960s Civil Rights Acts in the streets of Birmingham and on the highway between Selma and Montgomery.

One important prerequisite for action is the discarding of the debate about whether or not to be in "the system." That is like telling a drowning man he shouldn't be in the water; he is, and so are we. We had better learn how to tread water, swim, or build boats, for the water rises higher every day.

What we need to be about now — and for many, many years to come — is a version of politics which cannot be labeled by any of the old terms. If there is an opening for an American era of politics different from the past, then it must be a citizens' democracy, insurgent, with its focus seriously aimed at power.

When I speak here of "democratic" and "democracy," I do not mean the political party presently out of power, or the system of selecting government leaders as presently practiced in America; I mean the system of equally distributing wealth and power in an organized society, through institutions based on the premise that we all have equal ability — and equal right — to make decisions about our lives and our future.

This will require the creation of a large cadre with the strategy, skill and vision to build a democratic movement in the mainstream — a reassertion of the plain truth that ordinary women and men have the common sense and ability to control their lives, given the knowledge and the means.

The instruments involved in building such a movement are more than electoral races, as important as they can be. The lesson we ought to have learned from the sixties is this: A mass movement must have an organizational base. Without organizations that are stable, continuous, and mass-based, the movements that do emerge eventually flounder and decay; the sixties — in retrospect — were merely a series of mass mobilizations, winning impressive victories and inspiring great expectations, but ultimately unable to sustain a living democracy at the base of society.

We must develop a political program broad enough to attract a large section of the population, real enough to have some expectation of implementation, and human enough to solve the problems which blacks have in abundance and which most Americans have in some measure.

As a beginning, let us agree that we want:

• To guarantee all Americans an equal opportunity to participate in this society, and in the shaping of public and private decisions which affect their lives;

• To guarantee that no one goes without the basic necessities — food, shelter, health care, a healthy environment, personal safety, and an adequate income;

• To meet our obligations to assist in the peaceful development of the world's less developed nations and to desist from aggressive interference in their affairs.

To meet these goals, we must move radically away from an economy where the top one percent of the population receives more income than the bottom 20 percent, and where the richest 10 percent of the population receives the same income as the bottom 50 percent put together.

This redirection is a monumental task — its conclusion, after 200 years of struggle, is far from just around the corner.

Our goal is the elimination of privilege based on race or sex or class.

Our tools are our voices, our votes, our bodies, and our minds.

Fortunately, there are many Americans whose vision of their future does not match the view from the Oval Office. There is a sizeable body of opinion in America which refuses to surrender yesterday's goals to the occupants of power and the princes of privilege. But these — our countrymen and women, young and old, of all races, creeds, and colors — mistakenly believe themselves to be impotent, unable to influence the society in which they live.

Twenty years ago, black young people in the South sat down in order to stand up for their rights. They marched and picketed and protested against state-sanctioned segregation, and brought that system crashing to its knees.

Today's times require no less, and, in fact, insist on more. There is a large space created by the lack of effective political opposition to the selfishness that surrounds us — that space can and must be filled and the forceful opposition mobilized.

New voters must be registered and organized and educated and energized. The scattered and fractured constituency of progress — racial and language minorities, labor, the sexually oppressed, those for whom the American dream has become a nightmare — must mobilize their troops and lead them once again into the streets, against the barricades of apathy and indifference.

Less than 20 years ago, a sitting president, secure in his power, was forced to abandon plans for re-election as an angry nation shouted no to his plans for war financed at the expense of America's poor.

That shout should be heard again throughout America, at every ballot box, and every forum and every street corner where people gather and meet.

To accommodation with apartheid, we must say no.

To the reversal of racial equality, and defeat of the ERA, we must say no.

To the elimination of those programs that sustain life, we must say no.

To those who foul our air and water, we must say no.

To the planners of nuclear holocaust, we must say no.

To the forward march of militarism, we must say no.

We must say no to our self-imposed political impotence, to our seeming inability to organize and finance our own liberation.

We can prevail, and we shall endure, and we will overcome!

Tags

Julian Bond

Julian Bond was a founder of the Institute for Southern Studies and served as its president for several years. He was the communications director of SNCC, served in the Georgia state legislature, and was a professor at the University of Virginia.