Clinch River Breeder Reactor Bagged

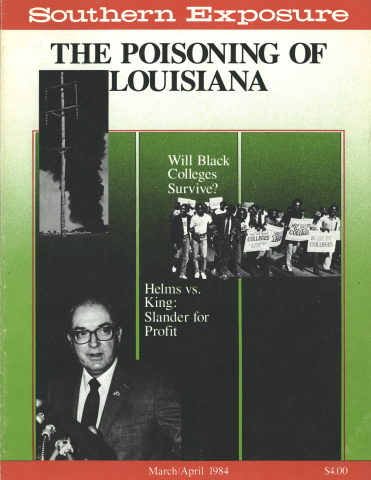

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 2, "The Poisoning of Louisiana." Find more from that issue here.

It was an unlikely marriage of interests: the right-wing Heritage Foundation and Ralph Nader's Congress Watch, the conservative National Taxpayers Union and the Machinists Union, the Council for a Competitive Economy and the Sierra Club. But this unusual coalition scored a remarkable victory in the Senate in October 1983, by defeating Senate majority leader Howard Baker's $8.8 billion "technological turkey," the Clinch River Breeder Reactor at Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

The victory was brewed from a lively blend of skillful organizing and exploitation of the shaky ground on which the breeder reactor plan stood. When the breeder was first proposed 13 years ago, its supporters offered skeptics the dream of unlimited energy. The nuclear plant, they argued, would demonstrate the feasibility of a process of producing electricity while breeding more radioactive fuel than consumed. Critics of the plant, however, pointed to a host of problems accompanying the development of this technology. The reactor, they said, increased the threat of nuclear proliferation by producing plutonium, the stuff of which nuclear weapons are made. Opponents of nuclear power maintained the plant was technologically unsound, while others saw the reactor as an ill-advised boondoggle conceived during a bygone era when electrical demand was skyrocketing.

Ultimately, however, the exorbitant cost of the reactor provided the focus for the anti-breeder campaign. "You could talk about the environmental and health and safety arguments until you were blue in the face," says Jill Lancelot of the National Taxpayers Union, one of the original anti-breeder organizers. "The economic arguments served as a bridge between liberals and conservatives," she says. Recognizing this fact, 15 environmental, peace, church, and research organizations from different points on the political spectrum forged the Taxpayers Coalition Against Clinch River in the spring of 1982.

The coalition adopted a two-front battle plan: a Washington-based blitzkrieg of lobbying, public education, and media work, and local organizing campaigns to build coalitions in 30 key communities throughout the country. The local coalitions mirrored the national effort, drawing together affiliates of groups such as the U.S. Farmers Association, the Audubon Society, the National Organization for Women, the United Mine Workers of America, the Steelworkers Union, Clergy and Laity Concerned, Friends of the Earth, Physicians for Social Responsibility, and the League of Women Voters. Catholic bishops in most of these communities lent critical support, as did many city and county officials. "The key thing was to put the breeder into terms people would understand . . . something people could easily relate to and become outraged by," says Craig McDonald, field director for Congress Watch and coordinator of the local organizing campaign. Organizers like McDonald made the economics of Clinch River hit home by translating the cost of the breeder reactor into what that money could buy for a community.

The local groups also proved adept at making the breeder a campaign issue during the 1982 congressional elections. In at least six Senate races opposition candidates brought the incumbents' voting records on the reactor into the forefront of debate. Three Senate candidates opposed to Clinch River — Paul Trible (R-VA), Frank Lautenberg (D-NJ), and Jeff Bingaman (D-NM) — won their races. And two challengers for seats in the House of Representatives, Rick Boucher of Virginia and Robert Toricelli of New Jersey, were elected after making opposition to the breeder reactor part of their platforms.

"Boucher's stand on the breeder made for a clear difference between us and our opponent," says his assistant, Andy Wright. "The breeder was one of the best examples we could give of foolish federal spending. We just went and showed how all those freed-up billions could be used to improve the lives of people in our district."

With the breeder's opponents dubbing it "turkey of the year," organizers had a chance to have some fun and get their point across in a unique way. As cameras clicked, Senator Lowell Weicker (R-CT), a Clinch supporter who ran for reelection in 1982, found himself caught in a revolving door with one of challenger Toby Moffet's campaign workers, dressed as a giant turkey. Steelworkers in Pittsburgh sent Senator John Heinz (R-PA) 12 frozen turkeys with the message "Freeze this Turkey." Senators Paula Hawkins (R- FL) and Arlen Specter (R-PA) received similar Thanksgiving gifts.

The Taxpayers Coalition nearly defeated the breeder in 1982 when, on two separate occasions, the project squeaked through the Senate by just one vote. The Senate, however, directed the Department of Energy (DOE) to devise a new funding plan that would reduce federal expenditures and increase participation by the private sector. That plan, proposed in August 1983, was spurned by many in Congress because it required taxpayers to shoulder the cost of building the breeder. According to the Congressional Budget Office, DOE's "cost-sharing" plan would be more expensive than if the government bore the entire cost of the breeder itself.

In September, coalition organizers launched a phone-tree campaign to undo DOE's proposed financing scheme. Working every night for six weeks, volunteers from Washington-based public interest organizations encouraged thousands of people in key states to send lunch bags to their representatives and senators inscribed with such slogans as "Bag the Breeder," "Don't Let the Breeder Breed," and "No More Pork at the Public Trough."

That same month the House voted against appropriating any more money for Clinch River. In the Senate, a much tougher fight was needed to counter the efforts of Senator Howard Baker, the project's chief supporter. Clinging to the breeder as a symbol of its faith in the future of nuclear power, the industry dispatched legions of lobbyists in preparation for the October Senate vote. President Reagan personally lobbied members of Congress, heavily courting the Congressional Black Caucus with the promise that a share of the project's contracts would go to minority businesses. But the coalition continued to hammer away with the facts, consolidating support among members of Congress and a very unlikely new bedfellow, the Moral Majority.

The Senate floor fight against the breeder was led by Senators Gordon Humphrey (R-NH) and Dale Bumpers (D-AR). Humphrey, a fiscal conservative who supports nuclear power, set the tone for the four-hour debate in his opening remarks when he said, "You do not have to support everything radioactive to be conservative. It is attentive conservatism to oppose waste, and this project is wasteful according to many experts." Bumpers provided comic relief by exposing the flaws of the DOE cost-sharing plan. "If you called up Mike Wallace and said 'Have I got a scam for you!' he'd hang up on you because it's so unbelievable," Bumpers said.

On October 26 the coalition's work paid off with a 56-to-40 Senate vote against further funding of Clinch River. Eight senators who voted to support the breeder in 1982 were persuaded to change their vote in 1983.

In the end, only the nuclear industry was left supporting Clinch River. "The idea of bringing the left and the right together in a coalition spelled the breeder's doom," says Scott Denman, a veteran organizer against Clinch River.

Tags

Jan Pilarski

Jan Pilarski is an energy activist and writer living in Washington, D.C. (1984)