This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 2, "The Poisoning of Louisiana." Find more from that issue here.

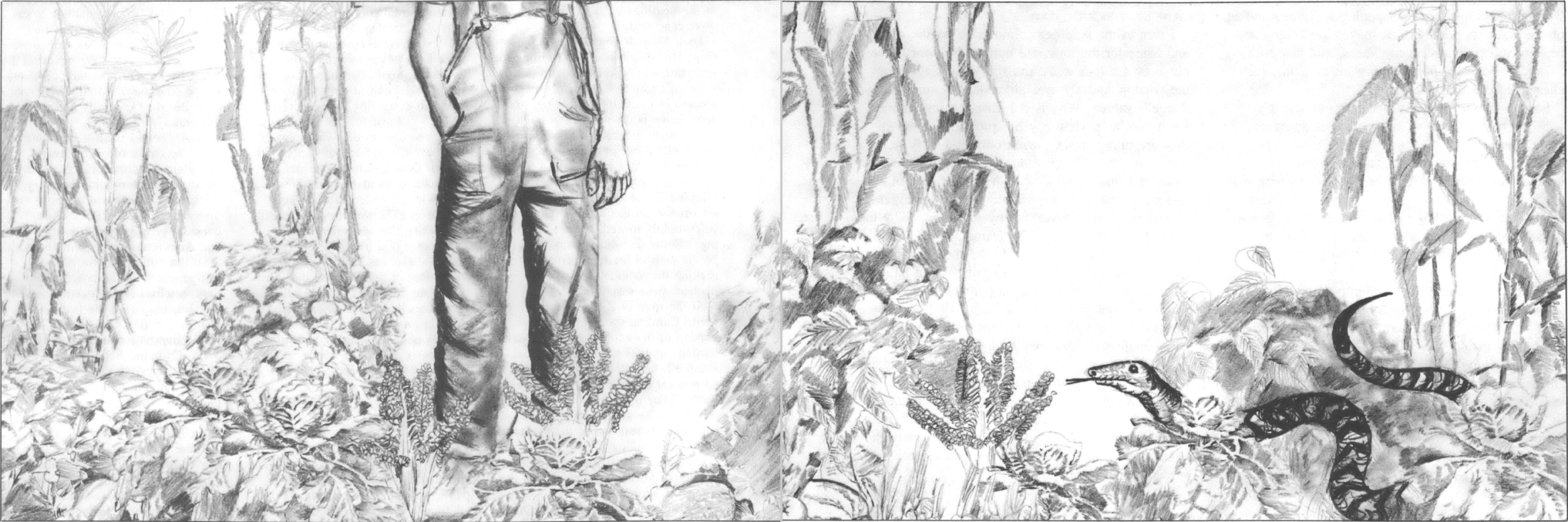

I watch Daniel in his garden. From the window above the kitchen sink, I see him stand there, his broad back to the house, his large head revolving — always moving, his huge arms hanging as if their size presupposes movement. It is his garden, beside his father's and in the farthest corner of the yard, but it is unlike the neat, weeded rows that Ely has planted. Daniel's rows are crowded and burdened. Except for the singular path he has made, there is no other entry into the bushy overhang, the rambling of vine and branch.

Every summer is the same. Ely plows both gardens and plants his own. We watch as Daniel takes seeds at random and casts them over his plot or stoops, and with a large thumb, pushes the seeds into the moist, pungent earth. A cantaloupe, some tomatoes, eggplant, cucumbers, more cantaloupe perhaps mixed with carrots or radishes, even pumpkin seeds and gourds — Daniel especially likes the ornamental gourds, snap and lima beans, corn, and peas — all mixed and growing profusely unaware of order and precision, crowding each other for sunlight, fruiting in Daniel's massive, calm hands in numbers that often exceed his father's pampered, planned plantings.

Beyond the gardens is a deep-green field of knee-high soybeans, and beyond that is the forest, brown-green against a light-blue mid-morning sky.

Daniel stands there for a long period not moving except for the predisposition of his head to revolve slowly, at times his chin slightly jerking forward. Usually when he moves it's to touch the growth for which he is responsible. He will hold a green cantaloupe or small cucumber and make his muttering sounds to it, as if urging its growth. He will run his big hand over the verdant leaves and buzz like a bee, and there are times when his meaty fingers move quickly and gracefully, like a slow butterfly, from leaf to leaf.

As I watch he slowly extends his heavy arm — a naked arm for he wears only bib overalls — picks a large green tomato and brings it to his gaping mouth where half of it is consumed with a slurping, sucking sound I can hear through the open back door. I wad the dish rag and squeeze it in a knot. He knows nothing of my anxiety nor does my anger disquiet him. Daniel's is a perfect world of moments, a complete world at any time, and, though I relinquished the natural hopes of a mother long ago, I nevertheless plug away at punitive measures that might change Daniel, might make him more cognizant of the complicated world in which we live. If only once he could see what's ahead of us!

He bites again at the green tomato as my anger takes control.

"Daniel!" I yell, slamming the screen door behind me, and I stand on the open porch wiping my hands on a yellow apron. I can smell the freshness of the blooming zinnias that stand along the porch and around the comer of the small house.

"Daniel!" again, and he turns, simple-faced, smiling. "I saw that tomato, Daniel," I yell, and he steps forward his head now almost on his chest. "Come here, son."

Coming across the yard, he stumbles, his huge feet bumping one another, but he rights himself and chances a quick look at me. His wet lips purse a "Mama," then he mumbles unintelligibly.

"What'd I tell you?" I ask knowing he will not tell me. This is for me. "I saw you eat a green-tomato. You know what I said I'd do if I caught you eating another one." He watches his wet-toe shoes. "You remember?"

I look down and see he is making the toes of his shoes move up and down. He is playing a game. His world is perfect, here and now.

I use a finger to get his attention, shaking it under his nose. "I said, 'Do you remember?"'

He looks at the finger, at his toes, at the finger. A new game.

"Didn't I tell you your stomach would hurt? Didn't I tell you you'd be sick again?" I question, hoping for remorse and not getting it. I am standing on the concrete porch which makes me taller than he, so I stoop, hands on my knees, and face him.

Daniel tries very hard to bury his chin into his chest, still watching the toes.

I reach forward, lift his face to mine, and try with my best grimace to convey my exasperation.

He smiles.

"What'd I tell you would happen if you ate another one? What'd I tell you, Daniel?" I bare my teeth, and Daniel slides a huge dirty index finger up his left nostril. "Okay, I've had it! Come in the house!" My harangue is no longer the third degree but quickly mutating into a conversation with myself.

"Lord knows I try. God Almighty knows I've given twenty-three years to trying. Time and again! Your father was here all day like me he'd see what I'm talking about."

I sigh heavily not wanting to forsake any of my arsenal on him and pull him with me into the kitchen. He stumbles on the threshold.

"Go to the sink," and obediently he does, stands there gazing out the window, an expectant look on his wide face as if there's something out there only he can see. "Open your mouth," I order and he does, slack-jawed, still looking to the far horizon, the blue sky reflecting in his calm eyes. "Wider. Yes. . . . You think my fingers enjoy fooling around in your mouth? God Almighty!"

I force the bar of soap into his mouth and I know the taste must be terrible, but he does not flinch, does not move. Then he looks at me as if he expected the soap in his mouth, as if this too is normal.

I move the soap around in there, place it back on the sink, and take the dishrag and wipe the inside of his mouth. When I hand him a cup of water, he drinks it down instead of rinsing. Knowing it's finished, he looks away from me, looks out toward his tangled garden then the sky.

"Okay, Daniel," I say, "enough's enough. 'Too much is a dog's bait,' my grandma used to say. No more green tomatoes!" I take his face and make him look at me. "No more green tomatoes."

Daniel smiles. He can break your heart, that boy — always could, and he rubs his wet lips against my forehead, thanking me, I guess, for what I've done. A heartbreaker.

One of his large hands goes to his crotch.

"Go on," I say, and he shuffles toward the hall. "And don't lock the door!"

I turn to the field peas simmering on the stove and listen for the lock. He bumps the door twice but does not lock it. At the sink I look again out the window and my eyes automatically turn to Daniel's garden. Why is it I always return there? Even in winter when Ely has plowed it over, my eyes are drawn to the barren corner. I walk in the yard and invariably gravitate to that spot of mute earth, that incomprehensible area, that area of forlorn testimony — my shame and my glory, the plot of my living mystery. Why me, God? Why me for twenty-three years? Why Daniel?

I have cried at times like this, a thousand times, more. But not now. I cried when he was a baby — when he was a boy I sat on the concrete stoop a whole summer of nights and I wept, but not now. There's something else where the sorrow used to be, something I think may be a stone.

Daniel returns to the kitchen, his pants unzipped but I don't correct him, and he ambles out the door, slamming the screen. He watches his feet as he walks across the yard. Their monotony seems to fascinate him. At his garden he stops, turns back to the house, and, not seeing me, pushes into the verdant touch of his plantings.

At twelve Ely comes in for lunch. He's been plowing soybeans and his shoulders are dusty and he smells of grease and dirt. As he washes in the kitchen sink, streams of dirt flow away from his hairy forearms.

"Hot this morning," he says turning to me with a small towel in his hands. He looks out the screen toward Daniel then back. "We'd a breeze till today. Must be rain coming though it ain't on the television."

We sit at the formica table, peas steaming, fresh cut tomatoes cooling beside slices of cucumber. There's a plate of cold ham between us.

Ely nods his head in Daniel's direction. "You gonna call him in?" he asks. I reply that Daniel can eat later and there is enough exasperation in my voice to quell his further comment, but as we begin eating the screen opens and Daniel comes in sliding his heels on the linoleum. Instead of taking his place, which is usual, he stands beside me, so close his trousers brush my arm. I replace a bowl of boiled corn-on-the-cob to the center of the table before turning to him.

"Well?" I ask.

He seems to study my hair.

"Sit down if you want to eat."

He does not move.

"Daniel."

Ely looks at our son.

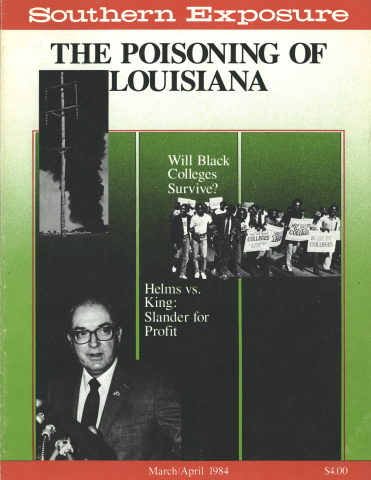

Slowly, Daniel raises his right arm to my face. He holds it so close to my face I cannot focus on the mark he is trying to show me. Pushing the arm away I realize there is a trickle of blood seeping like a red vein across his thick, muscular forearm.

"God Almighty," I say, more inconvenienced than frightened — it is only a small wound, perhaps a thorn, "what'd you do?" I push my chair back and rise holding the arm. "He's bleeding but I don't think it's more than a scratch. I'll get it. Come on, son," I say pulling him toward the sink. "He hasn't been a very good boy today. Green tomatoes again. Maybe this is his punishment."

At the sink the cool water washes over his forearm but the rivulet of blood continues to drip. I pull his arm closer, turning it over to search the soft inner arm, and find two small holes perhaps three inches below the elbow. With each of Daniel's heartbeats, blood spurts from the lower puncture.

Before I can call him, Ely is reaching over the sink, taking the arm, mashing it. His voice sounds very calm when he says, "Snakebite," but his face is white with terror.

By the time Ely has driven us the fifteen miles to the county hospital, Daniel's arm is swollen to twice its normal size. His chest and neck are becoming indistinct, and his large head is swelling so that his cheeks are bulbous and his nose is a protuberance of distended flesh. His ears seem to literally swell while I watch them. His eyes, now slits, are slowly closing. The lids are too thick to function.

He is laid on a table, and I hover over him, holding his other arm, his hand, and rub his thick forehead. Through a crevice of flesh I can see his eyes and I expect to see fear, but there is no fear, no alarm. He looks at me as if there is something he would say. I wonder if he knows what's happening to him.

"Daniel," I say.

He looks away from me to the overhead light and he seems to be very calm. His eyes are the same blue as when he looks out the window.

His breathing grows very heavy, and the nurse across from me says his trachea is closing. A young doctor I do not know swabs at Daniel's throat with what seems to be iodine while the nurse hurriedly opens a plastic pack containing a tube.

Suddenly I am pulled away from the table and a curtain is drawn around Daniel. The hands holding my arm are old and belong to Dr. Jefford. One hand goes behind my back and I feel him rubbing me between my shoulders, softly, just a touching. We stand together with Ely.

"We need to start antivenin right away," Dr. Jefford says. His face is lined with myriad wrinkles. His eyes, like Daniel's, seem too calm for this place. "We don't know what kind of snake but I think we can narrow it down." He takes an ink pen — the old refillable kind — from his pocket, unscrews the cap, and makes two dots on his own thin forearm. "I've measured the distance in the fang punctures to be an inch which means it's either a moccasin or a rattler. Because of the antivenin, it's important to know. We'll have to pick one and go with it." His patient eyes hold Ely's face, watching Ely's thinking and waiting for his choice.

Ely sucks air over his teeth. "Rattler, Henry. Got to be. I ain't never seen a moccasin that far up from the creek."

Henry Jefford nods, turns and ducks behind the curtain. Shortly he comes back.

"Let me tell you what we've got," he begins. "Has to be a large snake. An inch between fangs is pretty big, and the marks where the lower jaw struck," — he places two lean fingers on the blue dots on his forearm and uses his thumb to mark the snake's lower jaw placement — "are two and a quarter inches from the punctures. Also, the left fang penetrated a good size vessel — that's the spurting you saw, which means the poison's being routed through his body. You can tell from the general swelling it's moving around pretty good." He puts his right hand on my shoulder. ''The problem with antivenin is large amounts of it can precipitate lung damage, can cause the lungs to bleed . . ."

"You mean he'd drown in his own blood," Ely says.

"Let's see how it goes," says Jefford, his finger tapping my shoulder. "He's a strong boy, always has been."

Within four hours it is evident that if Daniel is to live massive antivenin doses must be given. His body is unrecognizable. His eyes are now only slits in his taut skin. The massive shoulders and chest have so swollen that the skin seems paper thin, opaque. Several tubes come from his enlarged arms, and there is a tube at his throat.

At midnight Henry Jefford comes to us in the dim hall outside Daniel's room. This time his bony hand finds Ely's shoulder. Softly, "I want you to be ready," he says, looking first at me then Ely. His eyes have not changed but his old face seems beaten. "We're going to give Daniel a very large dose of antivenin. If we don't he won't make it much longer. If we do he may not make it either."

I feel myself sinking against Ely. I smell his shirt and feel his strong arm hold me.

"What are his chances?" he asks, and the words seem to come from far away, almost don't come.

Henry Jefford rubs above his upper lip with an index finger. "I've been his doctor all his life and always thought with his temperament and strength he'd be here long after I was gone. Now this. He's as strong as anyone I know — stronger, but all this may be too much. His heart may not hold out."

From Daniel's door a nurse emerges and motions to Henry Jefford. They whisper by the door and Henry comes back to us. His face is ashen, his eyes, for the first time, seem spiritless.

"Ely," he says, taking our hands, "would you pray with me?" and suddenly, almost inaudibly he is repeating the 23rd Psalm, imploring God with gentle words that well within me, filling a long empty hollow where the psalm is firstly echoes but soon is quiet waters, a field from my youth where I lay in pungent earth and grass watching evanescent clouds — filling, filling until I stand away from Ely and hold myself, resuscitated, able. I know then that Daniel is dead.

We follow Henry into the room. The nurses are loosening wires and winding I them around projections on a bedside machine. We stand by his still bed.

"I washed his mouth out with soap this morning," I say. "He just stood there looking at me and out the window. I even put the soap in his mouth, but his eyes never changed. I think he could see things I could never see."

Ely holds Daniel's hand.

I want Daniel to forgive me, not just for the soap but for the twenty-three years. But he had never said it and now he could utter no saving word. I study his swollen face.

I walk to the door, wrapping a handkerchief around my knitting fingers, turn once more to see him, watching again in my mind's eye from the kitchen window, and leave him. Outside the night is clear. I stand there for a moment overwhelmed by the enormity of darkness, and I wait for Daniel's death to wash over me in quiet wringings of anguish and grief. I should weep at this. I should be distraught and tom.

Since there are no tears, I look for a sign, some indication I have done my part. I wait.

Finally Ely comes out and we go to the truck. All the way home there is no sign, nothing.

As Ely cuts on the lights in the kitchen and begins to make coffee, I go out to the back porch and try to look over the yard at Daniel's tangled garden. I can barely make it out. The darkness takes me, takes my eyes, and I see only the heavens. Watching the stars I think how scattered they are, how randomly strewn, how curiously mingled, crowded, and spaced. There seems no pattern, no plan, as if done by some childish sower, as if Daniel had been there.

Tags

Andrew Borders

Andrew Borders is a free-lance writer living in Davisboro, Georgia. (1984)