This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 2, "The Poisoning of Louisiana." Find more from that issue here.

In 1963 civil rights opponents contended that the indigenous protest movement that King had come to symbolize was, as Mississippi Governor Ross Barnett put it, "part of the world Communist conspiracy to divide and conquer our country from within." South Carolina Senator Strom Thurmond agreed, asserting "that there is some Communist conspiracy behind the movement going on in this country."

Twenty years later Thurmond sounded a very different note, endorsing the King holiday bill "out of respect for the important contributions of our minority citizens." But at least one senator — North Carolina Republican Jesse Helms — and several syndicated news columnists seemed more than eager to trumpet the sort of charges Thurmond once favored. By so doing, Helms and his small band of allies brought national derision upon themselves and gave the King holiday bill what the widely respected journal Congressional Quarterly termed "a symbolic importance transcending its actual effect." At the same time, Helms was consciously and carefully crafting an issue he could exploit profitably in his 1984 re-election campaign. Even before the King measure was signed into law, thousands of mass mail fundraising letters detailing Helms's assault on King were on their way to previous Helms contributors, and racially divisive ads citing Helms's distaste for King were being readied for broadcast over North Carolina's airwaves.

Every year following King's 1968 assassination, Michigan Congressman John Conyers, Jr., introduced legislation to commemorate the civil rights leader's January 15 birthday with a national holiday. For several years the bills languished quietly, but late in 1979 a substantial majority of the House of Representatives voted in favor of such a measure — only to see it die without action in the Senate.

Early in 1983, with the twentieth anniversary of the famous March on Washington approaching, Conyers and Indiana Democrat Katie Hall launched a new push for passage of the King holiday proposal. Hearings were held in June, and on August 2 the House voted 338 to 90 to make the third Monday in January a federal holiday in King's honor, beginning in 1986. Among those supporting the bill were many conservative Republicans, including New York's Jack Kemp, Georgia's Newt Gingrich, and Oklahoma's Mickey Edwards, head of the American Conservative Union.

In the Senate, Republican majority leader Howard Baker placed the House-passed bill directly on the calendar but was blocked from holding an August floor vote by Helms's threat of a filibuster. When Baker finally called up the measure on October 3, Helms was ready with a three-part assault on King's record. Taking up the cudgels with special fervor, Helms asserted that King had been the puppet of certain advisers whose true loyalty had been to the Soviet Union, that King's private life made him unworthy of commendation, and that King's political beliefs were resolutely un-American.

On the first point, Helms alleged that King "kept around him as his principal advisers and associates certain individuals who were taking their orders and direction from a foreign power.'' Indeed, Helms charged, "King may have had an explicit but clandestine relationship with the Communist Party or its agents to promote through his own stature, not the civil rights of blacks or social justice and progress, but the totalitarian goals and ideology of Communism."

Massachusetts Senator Edward Kennedy characterized Helms's assertions as a "last-ditch stand against equal justice," and lamented that it was "really tragic" and "unworthy of the United States Senate" that the North Carolina Republican was making "allegations that are completely unfounded." Most of the specific charges had been aired by segregationists 20 years earlier and are blatantly false.

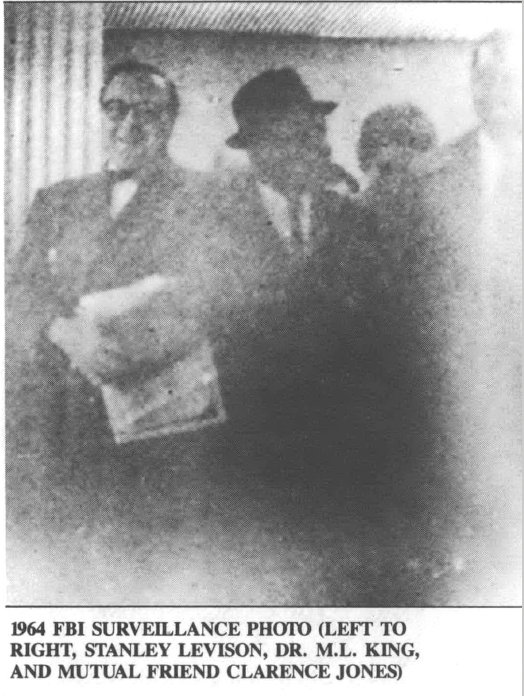

Helms focused on two King aides with Communist pasts. One, Jack O'Dell, whose party ties were the subject of FBI-planted news leaks in 1962 and 1963, held a low-ranking job in King's Southern Christian Leadership Conference and was not one of King's "principal advisers and associates." The other, white New York attorney Stanley Levison, was indeed one of King's closest confidants for more than a decade. He had been intimately involved in the most sensitive financial affairs of the American Communist Party (CP) in the early 1950s, before his close acquaintance with King.

The Levison-King relationship supplied the initial grounds for the FBI's infamous pursuit of King throughout the last six years of his life. Learning early in 1962 that Levison had been one of King's top private advisers since shortly after King came to national prominence in 1956, Hoover's bureau reconsidered its earlier conclusion that Levison's apparent termination of his CP ties made him no longer a suspect figure. As former FBI intelligence chief Charles D. Brennan revealingly explained in a 1983 comment, the bureau "had to operate on the assumption that Soviet direction must have been behind Levison's move from the Communist Party to Martin Luther King." That assumption led to constant electronic surveillance of Levison, but to the FBI's continuing dismay no evidence whatsoever showed that Levison somehow represented foreign interests in his relationship with King or influenced King in subversive ways.

That surveillance took place with the lull knowledge and written approval of then-Attomey General Robert Kennedy, and the FBI's overstated fears about Levison's role led both of the Kennedy brothers to warn King personally that he should terminate the friendship. When King maintained contact with Levison despite the Kennedys' warnings, the attorney general approved the bureau's requests for wiretaps on King's own telephones. The FBI's probe of the world-famous black leader moved into high gear.

Senator Helms combined his October attack on King with a demand that all of the FBI's surveillance materials be released before the Senate voted on the holiday bill. The most relevant materials — FBI documents detailing the contents of hundreds of Levison-King telephone conversations from 1962 through 1968 — already were public, the fruits of previous Freedom of Information Act requests. But Helms harped on the feet that some FBI tape recordings concerning King were sealed pursuant to a 1977 federal court ruling; he asserted that perhaps those items contained unrevealed evidence supporting his charges of traitorous activities. Attorneys representing Helms and the Conservative Caucus even went into federal court in an unsuccessful attempt to have the surveillance materials released.

Helms never acknowledged the fact that two different Ford administration Justice Department task forces had reviewed those items prior to their sequestering. Assistant Attorney General J. Stanley Pottinger reported in 1976 that his own firsthand examination revealed that the items were "scurrilous and immaterial to any proper law enforcement function or historic purpose," and that "there was nothing in the files, either in tapes or written records . . . that indicated that Martin Luther King was a communist or communist sympathizer, or in any way knowingly or negligently let himself be used by communists." Justice Department attorney Fred Folsom, who headed the second investigatory task force, reached an identical conclusion.

During the peak years of the FBI's pursuit of King, 1964-65, the bureau's principal interest was not the supposed influence of subversives on King, but the most intimate aspects of King's private life, aspects laid bare by the extensive — and expensive — campaign of under-the-bed buggings that Hoover's agents eagerly pursued in dozens of King hotel rooms. "It was muck that the FBI collected," former bureau intelligence chief Brennan publicly conceded. "It was not the FBI's most shining hour." Opponents of the holiday consistently alluded to this subject but never conceded that they were advocating a harsher standard of personal conduct with regard to King than that commonly applied to other prominent American political figures.

Beyond communist influence and sexual peccadilloes, the third aspect of Helms's October broadside was that "King's political views were those of a radical political minority" and that King himself had practiced what Helms termed "action-oriented Marxism." Although no fair-minded study of King's record would support that claim, Helms could and did select from among King's hundreds of public speeches a handful of phrases where King's criticisms of America's racial ills, economic injustices, and militaristic foreign policies had been particularly harsh.

King's 1967 attacks on the war in Vietnam brought him strong rebukes even from publications such as the New York Times and Washington Post, and his rhetoric about America's need for "a radical redistribution of economic and political power" also made some contemporary observers uneasy. His private, posthumously published declarations that "something is wrong with the economic system of our nation," that "something is wrong with capitalism," that "there must be a better distribution of wealth, and maybe America must move toward a democratic socialism," supplied additional grist for Helms's mill, but did not, even out of context, convincingly support Helms's contention that King's political beliefs were beyond America's mainstream ideological spectrum. King's commitment to nonviolence, his deep religious faith, and his lifelong dedication to justice and equality all belied Helms's attempt to paint King as something other than a fully patriotic American and man of God.

Following Helms's October 3 broadside, Senate floor debate on the King holiday measure was held in abeyance for two weeks while majority leader Baker persuaded the hard-core opponents to relent from parliamentary delaying tactics and allow a speedy, mid-month, final vote. When debate resumed on October 18, Helms distributed to his colleagues a thick binder of long-public FBI documents reflecting the bureau's virulent hostility toward King, materials he apparently believed would help support his earlier assertions. New York Democrat Daniel Patrick Moynihan, recalling his own acquaintance with King, angrily termed the binder "a packet of filth" and flung his copy to the Senate floor. Pressed by reporters to respond to Moynihan's attack, Helms answered bitterly that ''maybe they were filth because they accurately portrayed part of King's career."

When Edward Kennedy took the Senate floor to rebut Helms's charges, the North Carolinian responded by noting that the FBI's surveillance of King had begun during the administration of John Kennedy. Ted Kennedy's argument ought not to be with him, Helms insisted: "His argument is with his dead brother who was president and his dead brother who was attorney general." An infuriated Kennedy, stressing that his older brothers had deeply admired King despite their complicity in the FBI's surveillances, told the Senate, "I am appalled at the attempt of some to misappropriate the memory of my brother Robert Kennedy and misuse it as part of this smear campaign."

When Helms's series of hostile amendments to the bill were called up for votes, only a small handful of other senators sided with him. Helms charged that the ranks of the opposition were thin because "an atmosphere of pressure, intimidation, even threats" was present in the Senate, but numerous observers concluded that Helms's own conduct in opposing the bill had propelled some fence-sitters, concerned largely about the cost of adding a tenth federal holiday, into the ranks of holiday supporters.

Helms defensively insists, "I'm not a racist, I'm not a bigot," but some home-state onlookers think differently. "It's not anything new," according to former U.S. attorney H.M. "Mickey" Michaux, a black Democrat who ran unsuccessfully for Congress in 1982. "He's just got those deep-seated feelings. He's an individual who speaks his mind regardless of the political consequences." Others suggest that Helms, facing an uphill 1984 reelection fight, wants to appeal to conservative white North Carolinians or seeks a new issue for use in the mass mail letters he regularly sends out through his powerful fundraising organization, the National Congressional Club. They cite Helms's public admission that "I'm not going to get any black votes, period."

David Price, executive director of the North Carolina Democratic Party, says there was "no doubt that one of the prime reasons was to help Helms's nationwide fundraising." The evidence bears him out. Within days of the contentious Senate debate, Helms had letters in the mail asking previous financial supporters to make further contributions to enable his campaign "to recover from the liberal news media's and the left-wing black establishment's stinging, pounding attacks." Such criticism hurt his re-election chances, Helms said, and added, "We are hard-pressed to buy the TV commercials we need. Yet my campaign manager tells me that without new commercials now, we will slip even further behind." He also claimed, "We are scraping the bottom of the barrel right now because we have had to spend all our reserves on our 'grass-roots' voter registration drive to try to counter the voter registration drive of Jesse Jackson and the bloc vote extremists."

Helms's purported fund shortage could not have been too severe, for within a period of several weeks North Carolina television viewers were being treated to blunt ads in which Helms reiterated his opposition to the King holiday and questioned the position of his Democratic challenger, moderate Governor James B. Hunt. While Human Events, the self-described "national conservative weekly," printed Helms's entire Senate speech as a special supplement under the title "The Radical Record of Martin Luther King," right-wing columnists such as James J. Kilpatrick and Jeffery Hart further publicized Helms's diatribe in widely syndicated articles of their own.

Republican Senate leader Baker, noting President Ronald Reagan's promise to sign the King measure into law, sought to distance the G.O.P. from Helms when the final Senate vote took place on October 19: "I have seldom approached a moment in this chamber when I thought the action we are about to take has greater potential for good and a greater symbolism for unity than the vote we are about to take." Some cynical observers thought they saw electoral self-interest, more than sincere sympathy, in the flowery remarks of some holiday supporters, but the final Senate tally of 78 to 22 did amount to a tangible endorsement of King's remarkable career and the far-reaching achievements of the mass movement he symbolized.

Just when the Helms-King controversy seemed spent, Reagan reopened it that very evening by flippantly responding to a press conference question concerning King's political views with the remark, "We'll know in about 35 years, won't we?" — an allusion to the sequestered FBI tapes, sealed until at least 2027. Denunciations rained down upon the president, and a chastened Reagan telephoned Coretta Scott King to apologize. Former New Hampshire Governor Meldrim Thomson went public with a private letter from Reagan in which the president admitted he had "the same reservations you have" about King's character and affiliations. But no hint of these qualms appeared during the November 2 Rose Garden ceremony at which Reagan signed the bill into law in the proud presence of Coretta Scott King, her four children, and dozens of her husband's former associates.

In 1963 the shrill insistence of Southern segregationists that the burgeoning Civil Rights Movement was a Soviet handmaiden failed to stop the eventual enactment of the Civil Rights Act. But it afforded those demagogues yet another opportunity to exploit the racial prejudices of some segments of their electorates. To many Americans, the segregationists' verbal tirades only revealed the moral bankruptcy of their cause, just as did the police dogs and fire hoses of Birmingham.

Twenty years later, when three-quarters of both houses of Congress declared that the national contributions of the Civil Rights Movement merited a day of honor, Jesse Helms's strident objections failed to block the holiday, while also revealing the desperate lengths to which Helms would go in a carefully calculated attempt to raise the dollars and provoke the sentiments that might enable him to hang onto his seat in the Senate.

Many Americans may see Helms's conduct as the last flickerings of a dying mentality. But North Carolina's political insiders believe it is a conscious and potentially successful effort to further polarize the state's electorate along racial lines to serve Helms's selfish ends. Though some readers take at face value the plaintive predictions of gloom in Helms's fundraising letters, professionals with access to the private opinion polls know better. "Helms's stand against a Martin Luther King national holiday," the conservative magazine National Review joyfully told its readers early in 1984, "appears to have helped his candidacy, not hurt it." As even Democratic operatives privately concede, what once looked like an all-but-certain Helms defeat is now a dead heat.

Tags

David J. Garrow

David Garrow is author of The FBI and Martin Luther King, Jr. and Protest at Selma. He is currently completing a comprehensive book on King and the SCLC entitled Bearing the Cross. (1984)