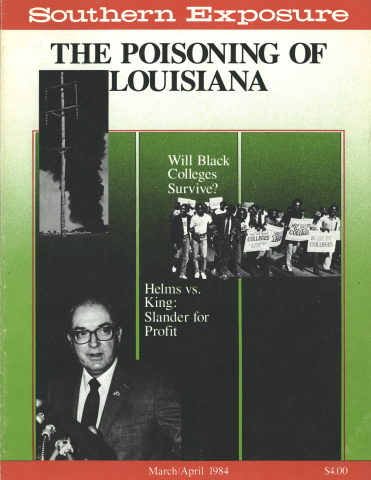

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 2, "The Poisoning of Louisiana." Find more from that issue here.

The state's most popular politician since Huey Long, Edwards was a conservative congressman in the 1960s. A more liberal Edwards first won the governor's office in 1971 and was re-elected in a landslide four years later. Ineligible for a third consecutive term, Edwards left office in 1980 with the highest approval rating of any outgoing governor since public opinion polls were invented.

Campaigning as a born-again New Dealer last fall, Edwards told voters, "You that are elderly and have seen your funds cut, you that are crippled, poor or disabled, take heart. Take heart for the great healer shall returneth and he shall make you well." Edwards spent $14.6 million in the course of this campaign — more than any other victorious gubernatorial candidate in U.S. history.

Beneath the colorful persona, however, is a different Edwin Edwards, and his hands are dirty. In the 1970s his administration opened Louisiana to massive chemical waste dumping by disposal firms and oil companies. The results have been devastating: concentrations of oil sludge and toxic waste have built up in bayous, tropical marshes, and farm soil throughout Edwards's Cajun homeland.

Louisiana now ranks fourth nationwide in generating hazardous waste. Some 183 million tons of waste effluents annually enter the state's rivers, principally the Mississippi. Most come from poorly regulated petrochemical plants. Landfills and deep injection wells account for another 26.7 million tons, while commercial toxic waste facilities store 394,315 tons of toxins annually. With 80 waste injection wells, Louisiana has roughly 25 percent of all such wells operating in the U.S.

Shortly after his re-election, Edwards outraged environmentalists by announcing that he would disband the Office of Environmental Quality, which had been established by outgoing Governor Treen. This office assumed regulatory powers previously held by the much-discredited Department of Natural Resources, which consistently opposed community leaders trying to shut down waste sites. Many people believe the new office was a real contribution to environmental progress. What Edwards will do next is an open question, but the fact is that much of the remedial work desperately needed results from the policies and actions of the environmental bureaucrats of his 1970s administration.

Louisiana has a spectacular history of political corruption. The late A.J. Liebling, comparing Louisiana's economy to Arabian sheikdoms, wrote that the state, "floats on oil, like a drunkard's teeth on whiskey." On a recent episode of "60 Minutes," Bill Lynch, the New Orleans Times-Picayune's veteran capitol correspondent, said of Edwin Edwards, "There's never been any question in my mind that he has run the government for his own benefit and for the benefit of his friends. . . . He's never been convicted, he's never been indicted, yet the scent of scandal hangs over him."

Hazardous waste is big business. Some $5 billion was spent in America last year to dump toxic waste, and the figure is expected to triple in the next decade. The three leading companies — Waste Management, Browning Ferris Industries, and SCA Services, Inc. — had combined revenues for all operations of $7.8 billion in 1982. In Louisiana, Edwards recognized the political largess of this new industry early on.

The earliest known deal involving Edwards began in 1972, when his executive assistant, Clyde Vidrine, helped a firm called BWS Corporation secure land at Tate Cove in rural Evangeline Parish, where Longfellow set his famous poem of the same name. Dumping began at the Tate Cove site with politicians paving the way. State Senator John Tassin told local officials the dumping would be safe. Dr. Ramson Vidrine, Clyde's brother, was Edwards's chief health officer; he gave the green light as well. And the state awarded BWS a waste-dumping permit.

By the mid-'70s Tate Cove was a lethal mess, and local citizens were outraged. Clyde Vidrine, meanwhile, had had a falling out with Edwards and told a reporter that the governor had made him get $20,000 from BWS before finding the land for the disposal firm. Vidrine said he gave the money to Edwards; the governor denied it. Finally, in 1982, the Treen administration began cleaning up Tate Cove with assistance from the Environmental Protection Agency's (EPA) Superfund. Legal action is pending against the Texas waste generators who used Tate Cove.

The Conservation Foundation recently studied the environmental protection laws of each state and ranked Louisiana forty-third. Among the reasons the foundation gave for such a low ranking are these: Louisiana requires no environmental impact statement for potentially dam aging development projects; it spends less than $2 per capita annually on environmental quality controls, compared to as much as $12 in some other states; and there is no state regulation of the development of floodways and floodplains — particularly important in Louisiana. The study's findings did not measure environmental quality of the states, only the laws. And it did not measure whether or not the laws are being enforced.

Louisiana's southern parishes are known as Acadiana, Cajun country, the namesake of the French Canadian province — present-day Nova Scotia — whose people migrated across the continent in the late eighteenth century. Steeped in the French patois, the region has for generations exuded warmth and celebration. It is a beautiful land, with fish, fowl, and mammals regenerating in the webwork of flora that buffers tropical prairies. This land is Edwin Edwards's home base. To most Cajuns, he is a folk hero, the first of their own to make it to the state mansion.

But his homeland has suffered under his stewardship. A 1979 Department of Natural Resources (DNR) study reflects an ominous image. According to this state inventory of chemical impoundments in south Louisiana, there are at least 2,700 industrial waste sites. In Vermilion Parish alone, 551 oil or gas waste sites were plotted, with another 49 of "unknown" origin. By an objective measure, it is a massive concentration. More critically, the vast majority of these sites lie above the Chicot Aquifer, a huge ground-water source. (See box on page 20.)

Chemical waste dumping in Louisiana has political causes and human effects. Vermilion Parish is a poignant case study that involves Benny and Pat Benezech, brothers who were big Edwards supporters. Pat flew Edwards to campaign rallies in his airplane. In November 1974 a breaking news report alleged that the Benezechs paid Edwards $135,000 to appoint Ray Sutton, a business associate of theirs, to the office of Commissioner of Conservation. Edwards issued a statement that the Benezechs were "well aware of my intention to appoint Mr. Sutton before they made the contribution." It was the conservation commissioner's job during much of Sutton's tenure to regulate non-hazardous landfill disposal operations, and Vermilion Parish suffered for it.

In 1976 a firm called Gulf Coast Premix — partly owned by Benny Benezech — negotiated a lease with deputy sheriff Alton Romero allowing it to dump industrial wastes at a garbage dump Romero owned and leased to the parish. As the chemicals built up and the rains came, oily run-off washed into neighboring rice fields and crawfish ponds. Still the toxic loads kept coming.

But Sutton refused to stop the flow of Premix wastes to Romero's land. Health officials wrote threatening letters but issued no halt order. In 1980 the attorney general filed suit, charging the pit was a public hazard. The day after the suit was filed, the pit caught fire and burned for two weeks straight. When the smoke cleared, Romero got on a tractor and prepared the soil for cultivation. The law suit was eventually dropped and DNR gave Romero permission to plant rice on the land.

In the opinion of Paul Jones, a leading Baton Rouge geologist, "Any area used for hazardous waste is a graveyard. It should be taken out of use. That is going to be a witches brew from now on. Those chemicals don't break down in time."

In support of the booming petrochemical economy of the 1970s, Edwards and Sutton took a lenient view of oil waste landfills. More production meant more waste, and it had to go somewhere. At the PAB oil site, also in Vermilion Parish, Alex Abshire earned $22,000 a month for accepting waste in three large ponds.

In 1981 Charles Hutchens, a lawyer in nearby Lafayette, filed suit against PAB and the waste generators on behalf of several families living around the site, alleging violations of the PAB permit to dump nonhazardous wastes. Hutchens cited soil tests revealing toxic chemicals and violations of the state's water discharge standards. The lawsuit did stop the dumping, but three years later the plaintiffs still await its cleanup. As the suit moves through the courts, Hutchens has used $12,000 earned in several out-of-court settlements to pay for the expensive, more sophisticated, soil and water samples needed for litigation.

Meanwhile, the plaintiffs live on ravaged land and wait for justice. In a house that has lost its monetary value, Dudley and Nona Romero (no relation to Alton) live different lives than before the dump opened. "We switched to bottled water," Dudley said in his heavy Cajun brogue. "Every time we drink tap water we get stomach cramps." Nona added, "It's not no ache, no! It's a pain like a knife cuttin' through your stomach."

"We are old," he continued, "not no young generation. But what about these grandkids of mine [who live next door]? If it's giving us effects at our age, what will it do to them if they live in it all their lives?"

There is no environmental "movement" in Louisiana. But there are a number of communities in the southern parishes afflicted by chemical waste, polluted water, and illness. Evelyn Allison is a woman in Vermilion who spent months canvassing families and recording their problems. She located disease clusters in two rural townships. One is near a pit owned by another parish deputy sheriff, Pershing Broussard. (See box on page 20.) The other is on Pecan Island.

The island, a beautiful tongue of land leading into coastal marshes, has long been a hunting enclave. But oil wells and disposal sites dot the area, and on-site waste disposal is only nominally regulated by the state. Ten homes in one community here have been hit by cancer or leukemia since 1975: there have been eight deaths from these diseases, and three people remain sick with them today. Vermilion Parish's overall cancer mortality rate is 6 percent higher than the national average. And despite the absence of heavy industry, only two U.S. counties have higher per capita incidences of intestinal tract cancer.

Dr. Gaulman Abshire of the hospital in Kaplan, a Vermilion Parish town, rattled off a list of his relatives who have been struck: "My uncle had leukemia; his son Dalton died of lung cancer. The daughter-in-law had cancer of the gum; they had to remove half of her face and one eye, but she's still living. My Aunt Estelle had cancer of the rectum. Her brother Renault died three years ago of leukemia. My great grand-niece, little Barbara, was in a group that went to St. Jude's Children's Hospital in Memphis [for leukemia]. She came through. Quite a lot of children have been struck. My sister-in-law had cancer of the pancreas but they found it early enough. They removed 90 percent of her stomach.

"It's not just the oil industry. Because of pesticides, there has been a steady decrease in the bird population here. You can't find a buzzard or crow around here for love or money. Years ago, when cows would die, the buzzards were everywhere. Now cows just rot."

In January 1983, 40 cattle were found floating in the Grand Marais bayou, which loops behind the Broussard waste pits, linked by a drainage ditch. Agriculture inspectors found small concentrations of lead in the stomachs of a few that had not decomposed. But no tests were taken on bones, ears, muscles, or fatty tissues, which are known to absorb chemicals and provide clues to the cause of death. No one knows whose cows they were, or whether others from the same herd were sent to meat markets.

The need for strong environmental safeguards — control not only of waste dumping but also of other factors, such as the dangerous pesticides Louisiana formers have used for years — was acute by the late 1970s. For his part, Edwin Edwards invested environmental responsibilities in DNR and tried to avoid media association with the problems. Toward the end of his second term, however, the Edwards administration's environmental policy had surfaced, and south Louisiana had become industry's toilet. Among the controversial policy actions taken:

• In 1979, as the state mapped plans to administer new federal environmental regulations, William Fontenot, an investigator from the state attorney general's office, asked DNR officials what they thought the new enforcement procedures would entail. "We were putting together our budget for the legislature," Fontenot recalls, "and needed to know their projected violations for any one given year. They told me the attorney general's office didn't need additional attorneys — because there weren't going to be violations. They were wrong, of course, dead wrong."

• Late in Edwards's second term, DNR paid Industrial Tank Company of California $350,000 for a study recommending construction of "the world's largest hazardous waste plant" in a congested industrial corridor on the Mississippi. The land is below sea level and is a proven flood plain. Industrial Tank (IT) came to Louisiana at the behest of Jim Hutchinson, a top Edwards man in DNR. The state awarded the company's hazardous waste permits in 1980, over the angry opposition of local residents. The plant has yet to be built, however, and the state's ethics commission has ruled that IT violated the conflict-of-interest statutes in its relationship with DNR.

• Carrying the Edwards administration logic into Treen's term, DNR announced in 1981 that the state's dump sites did not qualify for Super fund assistance — because they were not dangerous enough. This caused an uproar, including harsh newspaper editorials, that forced a reversal. Subsequent tests found seven sites heavily contaminated and eligible for EPA assistance.

While the bureaucracy under Edwards practiced favoritism toward waste dumpers, the governor's own relationship with Browning Ferris Industries (BFI) is a remarkable story in itself. More than any other waste dumping firm, BFI profited greatly by Edwin Edwards's callous disregard for people, land, and water.

A one-truck Houston garbage operation in 1967, BFI expanded rapidly in the 1970s by buying up small waste-disposal firms and their sites, pumping them with funds for expansion. Today BFI's stock sells well on Wall Street, and the firm has branched out into the Middle East. Louisiana was key to the expansion strategy by virtue of its proximity to the massive petrochemical complex strung along the nearby Texas Gulf Coast.

Edwards was raising money for his first gubernatorial campaign when BFI moved into Louisiana. The Jackson, Mississippi Clarion-Ledger reported that Sheldon Beychock, Edwards's 1971 campaign director and later his gubernatorial counsel, worked for BFI subsidiaries, one of which sent employees to campaign on company time. Once elected, Edwards chose E.C. Hunt, Jr., a Lake Charles lawyer and BFI lobbyist, to chair the commission designated to establish regulations governing waste disposal. Over the years, Hunt and Edwards remained fast friends. Hunt contributed $4,733.50 to the 1983 campaign, while BFI's Committee for Better Government in Louisiana contributed at least $4,000.

In 1972 BFI purchased land in Willow Springs, a hamlet bordering a swamp in Calcasieu Parish in the southwest corner of the state. The previous owners, Mud Movers, had been receiving wastes since 1968. BFI first stated its intent to dispose of water oil waste in a deep injection well, but state Health Department officials refused a permit. After a series of letters, they relented when the Conservation Department, under Ray Sutton, gave assurances of subsoil safety.

By 1977 BFI had won permission to receive toxic wastes at the injection well, and this appears to have been its intent all along. In December 1977 the Health Department wrote BFI granting permission for site expansion at Willow Springs; a large-scale landfill toxic waste business resulted, one which nets an estimated $1.5 million a year. The letter was the authorization by which BFI accepted thousands of tons of chemical wastes at the 45-acre site over the next six years. Even after 1980 federal guidelines mandated stiffer state regulations, DNR granted BFI "interim permit status" on the basis of the 1977 Health Department letter. As waste disposal continued at Willow Springs, BFI bought land elsewhere in Louisiana throughout the 1970s: three more sites in Calcasieu Parish and across the state in the towns of Darrow and Livingston.

In March 1977 a Baton Rouge firm called Southwest Environmental Company (SECO) purchased 382 acres in Livingston for $596,000. Governor Edwards's brother Marion was secretary of the corporation, and his brother Nolan's law firm handled the deal. In September a state water inspector informed Robert LaFleur of the Stream Control Commission that barrels of cyanide from another state had been found at the site. Despite a law requiring out-of-state loads to be registered with the authorities before being dumped, the state took no punitive measures, and the cyanide ended up in the Amite River.

When Livingston resident Charles Alligood began protesting, the Edwards law firm informed him in writing that SECO had won favorable comment from the Conservation and Health Departments and the governor's own Council on Environmental Quality. The letter ended by threatening Alligood with legal action if he didn't "terminate" his criticism. In May 1978 SECO sold the land to BFI for $1.13 million, a profit of $534,000 in just 14 months. Nolan Edwards was attorney of record; Marion Edwards's real estate firm handled the sale; and E.C. Hunt represented BFI at state hearings which resulted in permits for hazardous waste disposal.

Meanwhile, the situation at Willow Springs worsened. In early 1978 an oil waste pit overflowed. State inspectors told BFI they could no longer release such waste without permission from Health and Conservation — as if such permission would make the practice safe. Then in May news broke that Allied Chemicals of Newhope, Virginia, had signed a contract with BFI to send toxic loads to Willow Springs. This triggered a local uproar, but the state backed BFI. Stream Control's LaFleur said BFI had the proper permit, adding, "Those people aren't polluting water or streams, according to our tests." By October, however, state inspectors had found ditches alongside the Livingston site contaminated by oily sludge. Again, no punitive measures were taken.

Then Willow Springs residents began organizing. The Rigmaidens, a family living behind the site, had been hit hard. Beaulah Rigmaiden, age 78, said, "When you get in to take a bath, you better have some grease on you. It burn like fire." Her son Herbert recalls, "Back in '77, they brought some stuff in, I think it was gas from one of the plants. I lost 39 head of cows. I saved one, sent him to the meat market."

"There's enough pathology on that farm to keep a team of environmental scientists busy for five years," Dr. Stanley Smith, a pathologist at the Calcasieu hospital, told Cathy Osborne of the Times-Picayune. "I don't see how anybody could go and talk to those people and come away with any conclusion other than they've been poisoned." In an interview with this writer, Dr. Smith spoke of illness clusters found in medical studies: "The problem is that we don't know in the long run what those substances will do. Asbestos poisoning didn't appear for 15 years. Here, you are talking about thousands of chemicals about which little toxic impact is known."

In February 1979 LaFleur gave BFI permission to discharge waste off-site after heavy rain. BFI did it at night through a pipeline leading into the swamp behind the Rigmaidens' farm. When the discharge was discovered by a local health inspector, Calcasieu district attorney Leonard Knapp began an investigation. LaFleur later conceded he had not given written permission for fear of local opposition. E.C. Hunt, defending BFI at a local hearing, argued that no violation had occurred because no pollution was proven. But Herbert Rigmaiden recalls: "I came up with six more dead cows. I cut one of 'em open — smelled just like the stuff over there in those pits. Natural Resources is just lyin' to us. They ain't worth a plug penny."

In mid-1979 BFI was in trouble for its waste operations in Darrow. BFI had purchased the site from Gulf Disposal Services, whose secretary was Sheldon Beychok, Edwards's former campaign director. By now a pattern had emerged: Edwards's campaign aides, gubernatorial assistants, and brothers had helped BFI find Louisiana land for expanding its toxic waste disposal operations.

When the state attorney general's office turned its attention to environmental violations at Darrow, Edwards sent an aide to meet with DNR and state lawyers to negotiate an out-of-court settlement of complaints at Darrow and Livingston. BFI paid $50,000 to settle the dispute, a nominal amount compared to its profit margins. Then DNR applied to EPA for $98,000 to clean up Darrow and work on another BFI site in Sulfur — in effect, asking for federal funds to assist a firm just fined for polluting. EPA denied the request.

By the time Edwards left office in 1980, BFI was deeply entrenched in Louisiana. The lawsuits mounted. Neighbors of a BFI-owned garbage dump in Calcasieu Parish allege that chemical run-offs violate its solid waste permit. The Sulfur site is embroiled in separate litigation with the previous owners and the attorney general's office. And while parish district attorney Len Knapp mounted a legal challenge to BFI's Willow Springs permit, area residents lodged a multi-million-dollar damage suit. Just as in Vermilion Parish, the parish environmental organization in Calcasieu took form because people living around the waste pits couldn't get them closed through state bureaucracy. "The state serves hazardous waste dumpers," said Shirley Goldsmith of Lake Charles, "so we have to fight the state."

When BFI appealed to the Environmental Control Commission (ECC) for site expansion at Willow Springs, the legitimacy of its waste dumping permit — that 1977 letter from the Health Department — was questioned by Knapp. The commission met in April 1983 to rule on BFI's permit standing, and the company backed down from its expansion request. By this time, three years had passed since Edwards had left office, and ECC was having second thoughts about BFI's activities at Willow Springs. Nevertheless, BFI requested an extension of its "interim permit" until 1985, when a Texas facility is scheduled to come on line.

Representing the Calcasieu citizens' group, Knapp attended the April hearing and asked the commission to close Willow Springs immediately. He was armed with medical reports, a hydro-geological study showing chemical leaching into the Chicot Aquifer below the site, and a University of Texas School of Public Health report commissioned by the ECC. The report noted, "Drinking water samples afford some evidence of contamination." It concluded that chemicals were migrating from BFI and "appear to present a potential environmental problem."

DNR had supported BFI all along and interpreted the 1980 EPA guidelines as giving companies a grace period to renovate waste dump sites to meet new standards while operating under old permits. Moreover, a questionable state law absolves disposal firms of violations occurring before the 1980 regulatory changes. For its part, BFI offered the explanation that the documented leaching of chemicals into the aquifer beneath the site was the result of waste disposal by the site's previous owners — who sold it to BFI 12 years ago. The ECC, in trying to please both sides, told BFI to cease receiving wastes by December 31, 1983. That meant eight more months of profits for the company.

Then, in July 1983, a report by Eugene Senat, a geologist working for the Louisiana State University Environmental Studies Institute, found "recurrent problems of leakage" at BFI's injection well at Willow Springs. Commissioned by the Conservation Department, the report found serious fault with that agency's regulatory practices regarding injection wells. DNR was outraged, the conservation commissioner condemned Senat, and BFI slapped him with a $3.2 million defamation suit. Senat's report, based on Conservation Department records and site inspections, concluded that "many of the people involved in the permitting of the wells, as well as those enforcing the regulations, have displayed an incomplete and inaccurate understanding of various program regulations."

History has a way of catching up with even the most confirmed ideologues. Such are the ironies of Louisiana political cycles that David Treen, who as a congressman consistently opposed environmental reform legislation, as governor slowly woke up to the fact that something is wrong in the woods down here. He never understood it fully because, like Edwards, he got his big campaign money from industry. But in his own way Treen did begin to engineer reform. He began cleaning some of the waste dumps and he improved water monitoring along the Mississippi. But his most important change, taking environmental enforcement out of the Department of Natural Resources and investing those powers in a new Office of Environmental Quality, has already been declared unconstitutional by Edwards.

Edwards has promised a new environmental department. "It will be properly staffed," he says, but by whom? The architects of his administration's deplorable policies at DNR — B. Jim Porter, Gerald Healy, and William DeVille — have all kept their jobs. And the new DNR secretary is William Huls, an oilman who ran the department in the 1970s when the worst decisions were made. What is Edwin Edwards's word worth?

His record on waste dumping has surfaced in scattered news reports across the state, but his environmental record was not particularly damaging as a campaign issue. If there is a flame of hope, it is this: the man is a political genius who moves with the times. On many social issues his record is admirable. Perhaps he will wake up to the human suffering caused by environmental damage. But the critical state of water quality in Louisiana is clear. If the waste sites don't get cleaned up the economic and human repercussions will be staggering.

In mid-January 1984 the most expensive governor in America retired his campaign debt by flying 618 supporters to Paris for a week of celebrating. Most paid $10,000 a head, and the trip reportedly netted $4 million. His old friends are still with him. Sheldon Beychok, the former BFI man, bought a $10,000 ticket. So did Benny Benezech. In fact, when Edwards was photographed meeting President Francois Mitterrand of France, Benezech was seated right next to him.

While the high-rollers celebrated in Paris, the people of Willow Springs waited anxiously as BFI fought the site closure ruling all the way to the state's Supreme Court. Willow Springs citizens sent a bottle of local water to the high justices in symbolic protest against BFI, but symbols carry little weight in a court of law. The court issued a stay, giving BFI permission to keep accepting toxic waste after the December 31, 1983, closure date. As this article goes to press in late February, the court has reached no decision. And a remedial clean-up plan, ordered by the Environmental Control Commission last April, has not met ECC standards. Clearly BFI is digging in for the fight, no doubt pleased that Edwin Edwards will soon be governor again.

Just before leaving office in 1979, Edwards met with a group of concerned citizens. Ruth Shephard of Willow Springs recalls: "We went over to the governor's mansion in the afternoon. Edwin came tripping down the stairs in an expensive polo shirt. We had 22 ideas for new environmental laws. Poor Charles Alligood read three of them. Then Edwards said, 'Y'all have to present it to the environmental department.' Then he pulled off this diamond ring and tossed it to the gentleman across from me, a jeweler. We passed that stupid thing around. We were supposed to gawk at it. Then he took the ring back and we were ushered out the door. That was the end of our audience with the governor."

Tags

Jason Berry

Jason Berry is the author of Amazing Grace, a memoir of civil rights politics in Mississippi, and co-author of Up From the Cradle of Jazz: New Orleans Music Since World War II. (1991)