This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 2, "The Poisoning of Louisiana." Find more from that issue here.

A college must root itself in the group life and afterward apply its knowledge and culture to actual living. In the same way, a Negro university in the United States of America begins with Negroes. It is founded, or it should be founded on a knowledge of the history of their people in Africa and in the United States, and their present condition.

W.E.B. DuBois

"The Field and Function of the Negro College," 1933.

Most civil rights activists and progressives are aware of the growing national retreat from school desegregation programs. In the past two years serious efforts to scrap desegregation plans have been mounted across the country, and particularly in a number of Southern cities: Jacksonville, Florida; Little Rock, Arkansas; Memphis and Nashville, Tennessee; Augusta, Georgia; and Norfolk, Virginia.

In every city named, white moderates and conservatives have called for sizable reductions in the number of local schools which are scheduled for desegregation, and major increases in the number of all-black public schools. And despite substantial social science research proving that black academic achievement scores have improved since desegregation, many black leaders — including heads of local NAACP chapters — have acquiesced in the retreat from busing and other desegregation policies.

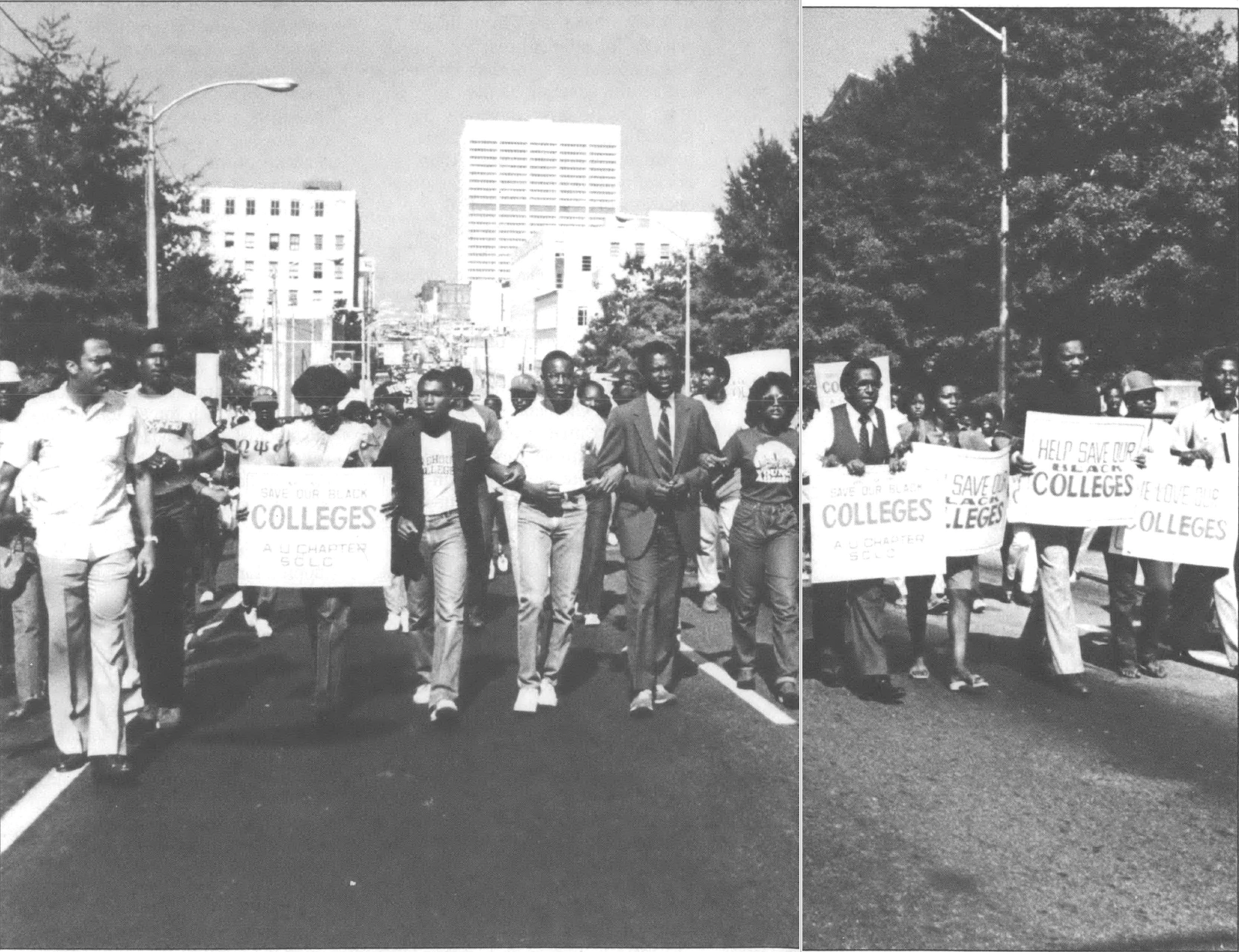

What has attracted little attention outside the South is another educational crisis which, if left unchecked, will have an even greater impact on blacks: the status of both private and state-supported black colleges.

The Catch-22 of Desegregation

Desegregation plans effected by the courts to improve black higher education have often ironically resulted in a deterioration of formerly all-black institutions. On November 3, 1982, for example, civil rights attorneys George Barrett and Michael Passino filed a motion in federal court in Nashville which charged that "desegregation of Tennessee higher education has failed." Tennessee State University (TSU), an all-black institution, was merged with the overwhelmingly white University of Tennessee-Nashville under court order in 1979. The new suit declared that TSU "has regressed to previous black-white ratios," as many white faculty, students, and staff have left the university; the suit also claimed that no progress has been made in improving the quality of TSU academic programs. In an interview, Passino stated that TSU students' performance on graduate and professional exams is "way below the national average." As far as the state is concerned, he said, "TSU ends up getting the short end of the stick," in part "because it was established as a black university by statute." White public universities "are also not meeting desegregation guidelines," according to Passino.

Tennessee State's problems are mirrored at more than 60 other black public institutions. In the 1960s and early 1970s, a number of historically black colleges were forced by Title IV of the 1964 Civil Rights Act to merge with neighboring all-white schools. All-black Maryland State College became the University of Maryland-Eastern Shore; the University of Arkansas incorporated all-black Arkansas A&M. As a result, many black educators and alumni of these black institutions claimed, with some justification, that desegregation had destroyed their ethnic identity and had actually reduced the educational opportunities available to many blacks. By the early 1980s, Lincoln University in Missouri, West Virginia State, and the University of Maryland-Eastern Shore all had majority-white student bodies. Delaware State and Maryland's Bowie State were over one-third white, and Kentucky State's student population was 49 percent white.

A number of white faculty at black colleges brought lawsuits against their institutions, charging that "patterns and practices of racial discrimination against white persons" were present. At Alabama State University, for example, a white federal judge awarded $209,000 in back pay to 57 white faculty and staff who claimed "reverse discrimination." One bewildered black critic declared, "This is a strange racial phenomenon, as it was only 14 years ago that various white institutions in Alabama, including the educational, systematically excluded blacks as buyers, consumers, participants, and employees."

Problems at the 40 or so privately supported black colleges are even more severe. Founded largely by white liberal philanthropists and churches in the decades after the Civil War, institutions like Spelman College and Morehouse College in Atlanta and Tougaloo College in Mississippi served for three generations as the foundations of black learning. Despite the institutional barriers to quality education created by Jim Crow, these small colleges did a remarkable job in preparing black students for productive careers in the humanities and the natural and social sciences.

A brief review of the history of one such college, Fisk University in Nashville, provides an illustration. During the segregation era, Fisk was the home of a number of major intellectuals: NAACP leader W.E.B. DuBois; historian John Hope Franklin; sociologist E. Franklin Frazier; artists/novelists James Weldon Johnson, Arna Bontemps, Sterling Brown, Nikki Giovanni, John Oliver Killens, and Frank Yerby. A number of Fisk alumni joined the ranks of the black elite as leaders in the creation of public policy. Representing a variety of political tendencies, they include: U.S. Representative William L. Dawson; Marion Berry, mayor of Washington, D.C.; Wade H. McCree, U.S. solicitor general during the Carter administration; U.S. District Judge Constance Baker Motley; civil rights activist John Lewis; Texas State Representative Wilhelmina Delco; federal judge James Kimbrough.

Other Fisk graduates moved into the private sector to establish an economic program for black development along capitalist lines; an example is A. Maceo Walker, president of Universal Life Insurance Company. One out of every six black physicians, lawyers, and dentists in the United States today is a Fisk graduate. A similar profile could be obtained from Atlanta University, Morehouse College, Spelman College, Tougaloo College, Tuskegee Institute of Alabama, Howard University of Washington, D.C., and other black institutions of higher learning.

After desegregation, black students with the best records were suddenly recruited away from black institutions. Black faculty were also lured away by promises of higher salaries, smaller teaching loads, and better working conditions. Black middle class alumni of Fisk and Atlanta University began to send their own children to Yale, Oberlin, and Stanford. As operating costs increased in the 1970s, Fisk was forced, like other black private schools, to dip repeatedly into endowment funds to cover day-to-day operating expenses. In less than a decade, Fisk's endowment dropped from $14 million to only $3.5 million.

By the early 1980s, Fisk's cash flow shortages had become regular occurrences. Because of the school's "financial woes," stated President Walter Leonard in one press interview, he was forced almost every month "to raise substantial amounts of money to see that the payroll gets paid." On January 30, 1983, one day before pay day, the college had only $175,000, exactly half of the $350,000 needed to make the payroll. Leonard hopped on a plane for New York, Washington, and Boston and returned with $181,000 from corporate, foundation, and individual donors.

Literally every aspect of university life was affected by the fiscal crisis. In October 1982 the library halted all new book and periodical orders. Basic reference sources such as the Reader's Guide to Periodic Literature had not been current for nearly two years. The number of campus security guards was reduced by one-third. The condition of the physical plant deteriorated even more rapidly than in previous years, as carpenters and maintenance workers were laid off indefinitely. It was not unusual to discover rats and large roaches in classrooms and offices. Xeroxing, phone calls, and postage service were restricted. Many faculty members were forced to purchase chalk, paper, and office supplies out of their own pockets. Local Nashville businesses usually refused to sell materials to Fisk without payment by check and in advance.

Attack from the Right

With the advent of the Reagan administration, the political forces of reaction which once defended black colleges as being necessary "to preserve Jim Crow" have now determined for financial reasons that these black institutions must be closed. On July 28, 1982, Secretary of Education T.H. Bell ordered the end of all further student loans to institutions where defaults in repaying National Direct Student Loans totaled 25 percent or more. The cutoff affected 528 institutions, most of which were community colleges, technical schools, and business schools. Predictably, the largest institutions affected had students from working-class backgrounds or from minority communities.

At the top of the list were most of the major traditionally black colleges: Fisk University, Knoxville College, and Tennessee State University, Tennessee; Prairie View A&M University, Texas; Claflin College and Voorhees College, South Carolina; Cheyney State and Lincoln University, Pennsylvania; Wilberforce University and Central State, Ohio; Shaw University and Winston-Salem State, North Carolina; Tougaloo College and Jackson State University, Mississippi; Kentucky State University; Atlanta University, Albany State College, the Interdenominational Theological Center, Morris Brown College, and Spelman College, Georgia; Coppin State College and the University of Maryland-Eastern Shore, Maryland; and many others.

The campus-based National Direct Student Loan program was created in 1958, and since then has given $7.5 billion in loans to 6.5 million students. Most of the black recipients were first-generation students, and could not have attended college without federal support. From the vantage point of black campuses, Bell's decision seemed unusually cruel. It penalized current and prospective black undergraduates by closing off an important loan source during a time when black unemployment is at postwar highs. It penalized students who had not yet attended college for the sake of punishing those who had already graduated.

The impact of these and other budget cuts of the Reagan administration forced black administrators to scramble in a desperate bid for survival. Clariborne C. Davis, director of financial aid at Mississippi Valley State University, stated in a recent interview in the Chronicle of Higher Education that his school had lost approximately $100,000 in federal student aid since the beginning of 1983. "If we had the money, we might have had 200 to 300 more students," Davis notes. The students who could afford to attend Mississippi Valley "either are not going to college at all, or are attending less expensive community colleges. Careers could be sabotaged by a student's inability to attend a desired college because of a lack of money." At nearby Tougaloo College, Melvin Phillips, director of student financial aid, states that the lack of federal aid has affected the school's enrollment, or has forced prospective students into the "military service as a way to get college money. With 550 students, we can't afford to lose that many bodies."

At North Carolina Central University, the situation is even worse. According to Vice Chancellor Roland L. Buchanan, Jr., 90 percent of his university's 5,000 students rely on some form of financial aid. When North Carolina Central informed students that they could not postpone the payment of short-term debts this fall, "at least 20 students were forced to drop out when they could not meet the payments because their financial aid had been cut." Buchanan notes that a number of prospective students "have not been able to come to the university because they could not get adequate funds to sustain them while they are here. . . . I feel there is a responsibility on the government to provide opportunities for students who are poor, but who are capable of doing university work." Even at those traditionally black institutions where the tuition is extremely low, the impact of Reagan's budget cuts had been felt. At the Baton Rouge campus of Southern University, roughly 85 percent of the 9,500 students receive aid. Southern's vice president for student affairs, Clarence M. Collier, states that more undergraduates have had "to use the Guaranteed Student Loan program" just to remain enrolled.

The problems of black institutions transcend mere dollars and cents. Surveys by the National Center for Education Statistics, a research division of the U.S. Department of Education, indicate a general erosion in the number of blacks being trained in higher education fields. For example, between the academic years 1976-77 to 1980-81, black college enrollment increased by 3.3 percent, while the numbers of black high school graduates jumped by 20 percent during the same period. The number of full-time black graduate students in masters and doctoral programs remained the same during these years. The National Center notes that "the number of degrees at the bachelor's level or above awarded to black students slipped 1.6 percent from 1976 to 1981, to 82,000 from 83,400. At the master's level, the number of degrees awarded fell 16 percent for blacks and only 4 percent for whites." Only 10 years ago, about one-third of all black students enrolled in junior colleges. Today over 51 percent of all black high school students, and only 36 percent of whites, attend two-year schools. The vast majority of these black students never advance to four-year colleges. Between 1976 and 1981, the only major gain in black college enrollment was in vocational and occupational programs.

Predictably, the Reagan administration's response to the outcry of black educators and administrators has been contemptuous. For example, last year the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights ordered a study of eight colleges for the "effects of student-aid cuts on institutions with large numbers of black and Hispanic students." President Reagan succeeded in restructuring the commission in the effort to obtain a clear voting majority for his right-wing views on desegregation and affirmative action. As a direct consequence, this January, the commission voted 5 to 3 to cancel its study on black and Latino higher education. Hispanic Reaganite Linda Chavez, director of the commission, informed the press: "Unless the commission wishes to establish that federal student financial aid is a civil right guaranteed to members of minority groups, this project would appear clearly beyond our jurisdiction." Since the results of the study clearly confirmed the human destruction created by the budget cuts of 1981-83, the administration callously chose to bury the truth.

Fisk administrators anticipated the Reagan administration's moves and tried to offset federal cutbacks by extensive fundraising efforts. In February 1982, the board of trustees announced that it would seek $2 million by the end of June. But even though President Leonard conducted an additional, separate fundraising campaign, the total amounted to only $200,000 by that autumn. Facing an immediate fiscal crisis, Leonard candidly informed the Fisk faculty on October 14, 1982, of the serious nature of the problem. "I have tried very often to shield faculty and staff from very serious financial problems because I have always felt up to now that I've always been able to pull a rabbit out of the hat. I'm not sure how long I will be able to do that."

Leonard said he had stated when he came to Fisk in 1977 that the university "would not miss a payroll." But "given the way our economy is, the way people resent strong black institutions, I can no longer make that promise," he continued. When the Nashville press later published his remarks, Leonard added for the record that the "only way we can relieve ourselves of the problem is to solidify our efforts to raise money" and make even greater sacrifices. "I don't think we are suddenly going to sink without a trace."

Conservative Leadership Detrimental

The dilemma for black progressives regarding the increasingly problematical future of black colleges is the historic failure of these institutions to articulate a clear pedagogy and practice of liberation. Few colleges have ever been linked organically to the ongoing economic and political struggles of the black working class and the poor. Many black scholars of note have been fired from these schools for political reasons — and this tradition of authoritarianism is at least three generations old.

In 1927 Howard University dismissed one of the nation's most prominent literary critics, Alain Locke, and three other professors on questionable grounds. W.E.B. DuBois attacked Locke's firing as tantamount to the surrender of "the privilege of free speech and independent thinking" at Howard. In 1944 DuBois himself was fired from the sociology faculty at Atlanta University, prompting a national campaign against the school's tyrannical president, Rufus Clement. In 1949 and 1955, Fisk University's board of trustees fired professors who refused to testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. In 1981 Howard University administrators denied tenure to Marxist political activist James Garrett, prompting massive campus demonstrations. As a rule, black colleges are overtly hostile toward unionization among staff members and use every means at their disposal to displace radical and Pan-Africanist faculty.

Part of the reason for the authoritarian character of black colleges can be traced directly back to nineteenth-century educator Booker T. Washington. The founder of Tuskegee Institute in 1881 at the age of 25, Washington built his college in an era of extreme racist violence and overt political repression. Between 1882 and 1927, 304 black men and women were lynched or burned at the stake in the state of Alabama alone. After 1901 black voters in Alabama were effectively disfranchised for the next 60 years. Washington himself was the object of racist abuse and threats by extremist bigots, despite his accommodationist rhetoric and his emphasis on industrial and agricultural training.

Given the omnipresence of racist violence, one small mistake by a member of the Tuskegee community could have destroyed the college. Thus Washington created an administrative system at Tuskegee which rigorously regulated all aspects of student and faculty life. Students were taught discipline, an uncritical respect for established order, and an outward conservatism in social relations toward whites. Faculty could not protest against Jim Crow restrictions, and NAACP "radicals" like DuBois were viewed with undisguised contempt. Washington frequently spoke out against trade unionism, socialism, and any political movement which jeopardized the interests of his "Christ-like" philanthropists. To survive the long social nightmare of American apartheid, the Tuskegee model for black education discouraged intellectual innovation, radical cultural creativity, and any manifestation of social and political ferment which questioned white supremacy. But the result of accommodation was survival.

Seventy years later, the political conditions which forced the accommodationist style and reactionary pedagogy upon black higher education had been largely overturned. Yet the older structures of social conformity and regulation, a top-down administrative order, and the crude suppression of students' rights still exist to a great extent at black institutions. Washington ultimately lost his famous political debate with DuBois, as liberal arts, a humanistic education, and civic activism became an integral part of the black educational setting. However, Washington's authoritarian model for the administration of black colleges still holds sway, especially in the South. A number of black colleges still retain curfews for "girls"; others demand overt expressions of "loyalty" to the university as a prerequisite to tenure.

When I chaired the political science department at Tuskegee Institute almost a decade ago, I was informed by my division head that all faculty were expected to be available in their offices "seven hours each day, Monday through Friday." I replied that there was a fundamental difference between high school and college teaching, and that it was impossible for my faculty to do library research, grade papers, and so forth when they were mandated to sit in their offices every single day. My protest was ignored, and perhaps even excused, due to my relative youth and inexperience in functioning at a black college. An administrative "request" at Tuskegee was tantamount to a non-negotiable demand.

An analysis of the boards of trustees of black colleges reveals yet another reason that they maintain a legacy of authoritarian governance. Trade and technical-oriented universities tend to be controlled by powerful white corporate executives and conservative politicians. Tuskegee Institute's board of trustees, for example, includes James M. Roche, former chairman of General Motors Corporation; A. Edward Allinson, senior vice-president of Chase Manhattan Bank; Thomas P. Mullaney, president of Dart Industries; David Mahoney, chairman and chief executive of Norton Simon, Inc.; and William O. Beers, former chairman of Kraft, Inc. Members of Tuskegee's "Centennial Era" fundraising drive include Rand V. Araskog, president, chairman, and chief executive officer of International Telephone and Telegraph; the eccentric former chairman of the board of Bendix, William M. Agee; Nixon administration cabinet member Winton M. Blount; Ford administration cabinet member Donald Rumsfeld; and the president of Eastern Air Lines, Frank Borman.

The more liberal and humanities-oriented black private colleges usually have a greater number of black scholars and liberal whites but are still dominated by corporate capital. Fisk's board of trustees includes the distinguished black historian, Dr. John Hope Franklin; Dr. Wesley A. Hotchkiss, general secretary of the Board of Homeland Ministries of the United Church of Christ; and Roots author Alex Haley. It also includes multimillionaire Helen C. Vanderbilt; John W. Gamer, vice-president of 3-M Corporation; Albert Werthan of Werthan Industries; and Otis M. Smith, vice-president of General Motors.

A neocolonial dynamic also operates in the selection of the presidents of many black colleges. In theory, the senior faculty, top administrators, and alumni play a role in selecting them; in practice, black college presidents tend to be chosen by conservative black- and corporate white-dominated boards of trustees with little outside input. Black private colleges gradually received the "right" to be run by black administrators — for example, Mordecai Johnson's appointment at Howard University in 1926 and Charles S. Johnson's appointment at Fisk in 1947. With rare exceptions, however, most black presidents have not been distinguished by their scholarship; they have traditionally been conservative, personally and politically, and have perpetuated the climate of academic authoritarianism and hostility toward the left which their benefactors on their boards of trustees required. A few "Black Power era" scholars have won presidential posts at black institutions — for example, sociologist Andrew Billingsley at Morgan State University in Baltimore and black liberation theologist Cecil Cone at Jacksonville, Florida's Edward Waters College. However, the vast majority of black administrators are dominated by the corporate world, and have little if any sympathy for black studies and the radical pedagogical departures which gave birth to a new generation of black scholarship in the 1960s and early 1970s.

At many traditionally white liberal arts colleges decisions are made by tenured senior faculty, department chairs, and administrators. But at a black university virtually all power lies in the hands of the president. At some schools, black faculty are required to submit their course syllabi for administrative scrutiny before they can order textbooks. Faculty are sometimes disciplined for using "subversive texts," such as Ralph Ellison's Invisible Man. Some black private colleges aggressively discourage student unions from inviting progressive speakers to campus. I know of one college president who officially "banned" the local NAACP president from speaking on campus in 1982 on the grounds that he was too radical!

The Case of Fisk

The struggle for academic freedom and democracy at Fisk during the past academic year typifies the problems at other black institutions. Although they worked with no pay raises for three years, Fisk faculty had become increasingly disgruntled with other, non-fiscal concerns, particularly the decline in student enrollment. Before Leonard's arrival in 1977, the student enrollment figures had already begun to sag. In the fall semester of 1973, 1,569 students attended classes; four years later, autumn enrollment declined to 1,125. During Leonard's tenure, student enrollment continued to drop sharply — to 1,101 in 1979, 889 in 1981, 751 in 1982, and 700 in the autumn of 1983. A bitter two-week-long student strike over campus grievances in 1980 prompted the exodus of many students and probably dissuaded some prospective freshmen from entering the university.

In February 1983 the faculty drafted a letter to the board of trustees, declaring that the root of the enrollment problem was "poor communication by the administration, no accountability to the faculty and uncertain management." The faculty communication noted further that "at a time when the talents and energies of all persons at Fisk need to be focused on the revival of the University, the administrative leadership becomes more isolated, less communicative, stingier with information and apparently without a plan for renewal." Two senior faculty representatives, Gladys I. Forde and Carroll Bourg, attended the February board of trustees meeting, took notes on Leonard's comments and other statements during the sessions, and distributed them to other faculty.

When Leonard obtained a copy of the faculty representatives' report, he became outraged — to put it mildly. In an open letter dated March 17, 1983, and addressed to board members, faculty, staff, and students, the president accused the two faculty observers of "deliberately, knowingly, and maliciously misquoting and misrepresenting" his positions on major issues. "Demagogues and saboteurs will always be part of any institution," Leonard began. "Christ had Judas, and even before that God had Lucifer, Caesar had Brutus, America had Benedict Arnold, and black people have always had Uncle Toms and Aunt Thomasinas and, every once in a while, a few white missionaries who brought bibles and took the land. Fisk has people who fit and embody all of the above. There are not many of them, just a few, but then it only takes one rotten apple to spoil a barrel."

The president suggested that the faculty's "deliberate activities" were designed "to create confusion" and "to cover-up inadequate devotion" to teaching responsibilities. "A sickness which began many years ago has reached a point where only radical surgery will correct it," Leonard warned. In closing, Leonard asked whether "persons who demonstrate such intellectual dishonesty should be members of the Fisk University faculty? I wonder whether people who are acting in ways calculated to promote discord; to plant seeds of distrust; to introduce hate and bias; and, who attempt to undermine and disrupt efforts to preserve the integrity of Fisk, have any right to remain on this campus?"

Although many students still remained apathetic, others were outraged by the president's inflammatory remarks. The March 24, 1983, editorial of the student publication, the Fisk Forum, characterized Leonard's actions as "the 'wounded bear syndrome' . . . in which any animal, when wounded, will lash out ferociously and usually without a battle plan at anything it considers an enemy." Leonard's controversial letter was clearly "detrimental to the survival of Fisk," the Forum declared, adding that the president had "slandered" the faculty by calling them "a pack of liars," and that his "crude and manipulative" letter was "the most twisted piece of information students have received to date" about the ongoing university crisis.

Faculty members generally agreed that Leonard's response was an example of hyperbole, paranoia, and demagoguery at its worst. One week later, members of the Faculty Assembly cast a vote of "no confidence" in Leonard as president. Fifty-three of the eligible 73 members of the assembly were present. By secret ballot, 38 members voted for the motion, five abstained, and five voted against the motion. This unprecedented act of public censure represented a demand by the faculty that the trustees take some immediate measures to resolve the campus chaos.

Of course, Leonard retained some support among the faculty and alumni. One Fisk alumnus, Emma Byrd, circulated her own open letter among students, faculty, and trustees, denouncing the "uprising" against Leonard. "People have been dieing [sic] since Jesus for Negroes or Blacks to learn how to read and write!! Let us not get this far into orbit and self destruct!! Let us not go down as a sinking ship of educated fools because we simply acted a fool!!" Byrd praised Leonard as "an individual of high morals, and highly exposed, well learned, and well bred academic scholar. He is the university's savior!"

Leonard also won the support of most students in April by announcing a 10 percent reduction in tuition and fees for the 1983-84 academic year. Many faculty and students, however, wondered whether the financially troubled university could withstand such a drastic reduction in income. Several middle-level administrators and faculty leaders privately charged that the president's decision was motivated in part by immediate political considerations and was based on insufficient budgetary planning. The tuition reduction decision was also made too late in the academic year to attract more students to the next freshman class.

Several trustees finally stepped into the debate in April, and initiated a "Unity Committee" comprised of two board members, two administrators, and three faculty, including myself. Despite the end of public quarrels, the overall situation at the college continued to decline. For months at a time, the university was unable to pay into the faculty's retirement pension fund. The health insurance premiums went unpaid for several months, and in early March 1983 the company cancelled the faculty's insurance. Inexplicably, the administration decided not to inform its faculty that they and their families no longer were covered by health insurance. At least one faculty member had to threaten a legal suit in order for his outstanding medical claims to be paid.

In April, ARA Services of Philadelphia, which had provided Fisk's meal services since 1966, left the university because of an unpaid bill of $716,835. After a hectic series of negotiations, the administration agreed to repay ARA, and a new food service company was obtained. But Fisk's debts continued to mount. By mid-1983, the university owed the Internal Revenue Service almost $500,000 in payroll taxes. In late spring, IRS sent an official notice that $204,900 was "due immediately" — although Fisk had not made any substantial payments as of November 1983. Fisk also owed local utility companies about $465,000, as well as $3.5 million to the federal government for the construction of several dormitories. Not counting long-term debts, Fisk operated about $400,000 in the red in 1982-83.

Even after these problems, I was not yet convinced that I should leave Fisk. As the director of the Race Relations Institute, my hope was to revive the long-dormant division as a productive center for scholarship and fundraising. In the 1982-83 academic year the Institute held two successful conferences, one on the theme "Corporate Power and Black America," and a second on the "Arms Race vs. Human Needs." The later conference attracted 225 participants from 18 states and five nations (including a correspondent from Pravda), and was the first series of lectures and workshops on disarmament and the domestic impact of nuclear arms spending to be organized by black Americans. Yet part of the modest grant I had solicited to fund the later conference, once given to the financial officer in charge, became virtually inaccessible. It was only on the day of the conference itself that I obtained checks to cover the travel expenses of many invited speakers — money which had been requisitioned weeks before. Some conference participants who had been promised payment of travel expenses in advance had to wait one month to receive reimbursement. In two cases, I had to pay speakers' transportation costs out of my own pocket. I received no explanation why grant monies were unavailable, although no direct evidence exists indicating that the funds from this restricted grant had already been spent by the college. Nevertheless, the ordeal of struggling to recover grant money from recalcitrant officials, plus the month-to-month uncertainty of whether we would receive paychecks, and the lack of medical coverage for my three children and my wife, finally broke any hope I had to help rebuild Fisk. Faculty associates of the Race Relations Institute had already requested letters of recommendation to aid them in their search for jobs, and I provided assistance whenever possible. As late as early August, faculty members had not been given contracts for the 1983-84 school year. Sadly convinced that neither the board of trustees nor Leonard was able to address, and much less resolve, the crisis, I resigned. By early September 1983, about two dozen faculty and staff members had also left.

In late 1983, President Leonard resigned in the wake of a controversy surrounding employee pension funds. According to the Nashville Tennessean, in May 1983 Leonard "instructed the college to determine its indebtedness to his account — which he believed to be $14,000 — and to place $5,000 in an Individual Retirement Account" at Nashville's Commerce Union Bank, "$5,000 with Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner and Smith, and the balance in an account at the National Bank of Washington." The Tennessean also learned that Leonard "received pay raises of $5,000 in March 1981 and $7,000 in June 1982 giving him an annual salary of $60,000." Faculty responses were predictable. "That's deeply unfair and reflects what many faculty have suspected for a long time — the president takes care of himself but has neglected the faculty," professor Carroll Bourg stated. Even chairman of the board Timothy Donaldson, who claimed that he knew nothing about Leonard's pay raises and pension payments, told the press that if the allegations were true, "The staff there has something to bitch about." As fiscal conditions deteriorated, Leonard finally announced his departure, to take effect in June 1984.

Black faculty are generally reticent to speak on the record about the authoritarianism and lack of democracy at most black colleges. One faculty member at a small black college in Mississippi, however, describes his environment as "nothing short of a concentration camp." Another professor declares: "The president encourages bootlicking and bad faith. It sabotages everything he does. . . . There is an attitude of mistrust and fear. The president sets the tone and he's responsible for accelerating the brain drain from this school. The suspicion and the paternalism here is for students like going through hell. The students are taught two things: 'sit down and shut up' and 'cover your ass.'. . .Whenever things go wrong, the president either blames the board of trustees or the faculty. . . .We can't build a [viable] community when people are made to feel small." Faculty workloads of four to five courses per semester (compared to two courses at many white private schools) serve as a check on faculty scholarship and productive research. "The average faculty member is not motivated to do work," one faculty member states. "That any scholarship at all comes out of here means that people are 'hyperdedicated.'"

The number of horror stories people have told me are too numerous to mention. At one black college, the president expelled the entire student government leadership for raising issues related to democratic rights on campus. One college president verbally abused a group of students in a public forum and then threatened to take one especially provocative pupil behind the chapel to administer corporal punishment.

The Challenge

Despite these conditions, almost every black faculty member I have interviewed expressed the view that black colleges had to be defended and ultimately improved. "My commitment to the black school is stronger than money," one professor stated. "Teaching at a black college is a personal commitment to the black community. Without a strong black community, true racial desegregation is not possible. That's why we're needed here." One student protest leader described her education at her college as "the best years of my life." Many students and faculty want to challenge the gross failures of these institutions, but not at the risk of their continued survival. Few students at black colleges wish to transfer into majority-white institutions.

If indeed the decline of black colleges was the product of accelerated desegregation of formerly all-white institutions, one might be less concerned. Ironically, however, the collapse of black schools and cutbacks in tenure-stream positions for young black faculty are occurring precisely at a time when white colleges are reducing their numbers of black professors and administrators. At Princeton University, for instance, officials asserted recently that they have made "a vigorous effort to recruit black faculty members." In 1974, however, the number of black Princeton professors was 10, and today the figure has dropped to nine. By way of contrast, the number of women faculty at Princeton in the past decade has increased from 54 to 101.

Similar statistics can be cited across the country. At Harvard University in 1980 there were 34 black professors out of 1,746 faculty; in the spring of 1984, the number of black professors had declined to 24, about 1.4 percent of the total faculty. At the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the black faculty total only 2 percent; Cornell University, 1.7 percent; Stanford University, 1.6 percent. White administrators are quick to justify these small numbers of Afro-American faculty as a product of the relatively small pool of blacks who earn advanced degrees. But since 1974, the overall proportion of blacks receiving doctorates has risen from 3.7 to 4.4 percent. In 1982, the proportion of all minorities receiving doctorates in the field of psychology was 8 percent; mathematics, 9 percent; education, 14.5 percent; economics 13.4 percent; political science, 12 percent; and sociology, 10.7 percent. Even after factoring out Hispanics, Asians, and other people of color, these figures indicate that the majority of white universities are making few sincere efforts to hire black graduates. Consequently, the survival of traditional black colleges is of paramount importance to thousands of young black teachers and administrators, who have few avenues of employment outside these institutions.

The challenge of saving black higher education is a two-fold process. Politically, the right to preserve all-black educational institutions means that pressure must be exerted on the federal government to increase its support to these colleges. White progressives especially must comprehend that the battle to maintain a Fisk University or an Atlanta University as an all-black center for scholarship in no way contradicts the demand for a desegregated, pluralistic society. For the foreseeable future, white universities will employ every means, legal and otherwise, to reduce the number of black faculty, staff, and students at their institutions. Thus the effort to maintain black colleges is in essence the attempt to guarantee blacks access to higher education. Second, the pursuit of genuine democracy and a black pedagogy for liberation must be fought for within these universities, and any efforts waged by black students toward this end must also be supported.

W.E.B. DuBois observed at the seventy-first anniversary commencement exercises of Knoxville College in Tennessee on June 10, 1946: "Are [black] institutions worth saving? . . . I am convinced that there is a place and a continuing function for the small Negro College. [They] have an unusual opportunity to fill a great need and to do a work which no other agency could do so well."

Tags

Manning Marable

Manning Marable is professor of political sociology and director of the Africana and Hispanic Studies program at Colgate University. During the 1982-83 academic year he directed the Race Relations Institute at Fisk University. He is national vice-chair of the Democratic Socialists of America. (1984)