This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 2, "The Poisoning of Louisiana." Find more from that issue here.

Past the sign advertising live pink worms and minnows, past the fields of soybeans, corn, and melons, past the small town of Snelling, South Carolina, lies the Barnwell Nuclear Fuel Plant (BNFP). A series of square, unadorned buildings behind a chain-link fence, its only distinguishing feature is a massive stack. Fifteen years ago this plain-looking facility was expected to launch the next generation of nuclear power plants and transform energy production in the United States and, by example, the world.

BNFP seemed to have everything going for it in 1968, when a consortium of several of the world's wealthiest corporations, including Allied Chemical, Gulf Oil, and Royal Dutch Shell, formed Allied-Gulf Nuclear Services, later renamed Allied-General (AGNS). It agreed to purchase land in Barnwell County for construction of the plant. But in 1983, 15 years after concerned citizens started speaking out against BNFP, Congress pulled the plug on any additional funds to bail out the floundering project, and AGNS officials decided to write off the plant as a tax loss. Much of the equipment has been dismantled and sold, or given away. And where 300 people were once employed, in early 1984 only a dozen remained.

The battle over Barnwell is a story about organizing by grassroots groups, a swing in the political pendulum in their favor, and the economic boondoggles of the nuclear industry. It is a story about concerned citizens who, against all odds, money, and expectations, defeated the powerful nuclear industry and its allies in high places.

The Beginning

AGNS (pronounced "Agnes") executives chose to build the plant in South Carolina after high-ranking state officials lobbied for the project. Barnwell County, the chosen location, is also the home of two of the state's most powerful politicians, state senator Edgar Brown and state representative Solomon Blatt. Both, according to a state newspaper, had informed the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) that their state would offer a warm welcome to such a plant.

The county also plays host to a comer of the Savannah River Plant (SRP), since the early 1950s a major nuclear weapons manufacturing facility. County residents were originally skeptical about SRP's safety, but, having heard of no problems or mishaps there, they trusted nuclear facilities.

The governor's office, the General Assembly, the Budget and Control Board, the State Board of Health, and the State Development Board worked long and hard in convincing AGNS executives of the benefits of moving to South Carolina. In 1967 the state legislature passed the Atomic Energy and Radiation Control Act to encourage the construction of nuclear facilities in South Carolina.

Bolstering this political power operating on behalf of the nuclear industry were the economic arguments for BNFP. AGNS officials trusted the predictions of their economic advisers that the plant offered bountiful profit for the future. In the late 1960s and early '70s, orders for nuclear reactors were on the increase, and scientists could already envision the depletion of the world's supply of fuel for the reactors — uranium. Yet nuclear fuel rods, when no longer usable in a reactor, still contain most of their original uranium, still usable if retrievable.

The Barnwell plant was conceived to reprocess these spent fuel rods, turning the unused uranium into fuel. BNFP would take the spent rods, chop them up, and dip the pieces into an acidic bath to separate out the remaining uranium. This could then be made into new rods.

The plant would also remove the plutonium produced by the original nuclear reactions. In addition to its primary use — the production of atomic weapons — plutonium also offered the dream of unlimited energy production. AGNS officials planned to sell their plutonium to be mixed with uranium for use by nuclear power generators, but they were also betting that plutonium would eventually be used in breeder reactors — a new kind of reactor that would "breed" more fuel than it used in the power-generating process and make plutonium a never-ending source of fuel. (See the box on the Clinch River Breeder Reactor on page 50.)

Opposition Takes Root

The first person to speak out against BNFP was not an enemy of nuclear power. His name was Townsend Belser, and he had spent four years working for the navy's nuclear program under Admiral Hyman Rickover. There he gained extensive schooling in nuclear plant operations and toured government reprocessing plants.

In 1968 Belser, a 33-year-old patent attorney from a politically prominent family, saw a newspaper article about the planned Barnwell reprocessing plant. He was familiar enough with the reprocessing of uranium to question the decision to locate BNFP in an area like Barnwell, which has a high water table and is surrounded by extensive wildlife. "Admiral Rickover ingrained in us a very conservative philosophy," explains Belser. "We knew that we were dealing with a very dangerous technology if care was not taken."

Belser didn't oppose the construction of a reprocessing plant, but he did oppose the choice of South Carolina as the site for one. "If a plant like that was going to be built," he says, "it should be in a more sterile and stable environment." In late 1970 Belser testified against BNFP at public hearings in Barnwell. But his was a lone voice, and his arguments were pushed aside. The plant was licensed for construction that same year.

Belser remained unconvinced, and he began a one-person campaign to alert people to the dangers of the plant. He wrote to the governor, testified before the South Carolina House Judiciary Committee, and even asked Walter Cronkite to investigate.

Belser also described the plant to his friend Bob Wilkins, publisher of Sandlapper, a bimonthly state magazine. Belser's long, detailed article about problems at Barnwell was printed in the May/June 1971 issue and was entitled, "Is South Carolina to Become a Nuclear Dumping Ground for the Entire Nation's Radioactive Wastes?"

In the article he argued that a nuclear reprocessing plant could cause disastrous contamination of the environment, accidentally or by the regular, planned release of radioactive material out of the plant's stack. The article consisted of eight pages of detailed, turgid prose with only one graphic, a map — making for difficult and frightening reading. But it was read. Among those who responded with letters to the editor was Howard Larson, the president of AGNS, and J. Bonner Manly, director of the powerful State Development Board.

In challenging the plans, Belser spoke to every group he could find — social gatherings, luncheon clubs, environmental groups — and he took along reprints of his article. In 1971 he addressed the South Carolina Environmental Coalition, an amalgam of conservation organizations and garden clubs. Among those who picked up a copy of the Sandlapper reprint there was Ruth Thomas, a 51-year-old housewife who was the Audubon Society representative to the coalition.

"I read it that night," remembers Thomas, "and didn't sleep all night. I called Townsend first thing in the morning and asked him what I could do. I said I'd do anything. He suggested that I talk with the Audubon Society, and try to get the whole group interested."

Thomas spoke to the Audubon Society, the Sierra Club, and the Columbia Women's Club, and as she did she began to immerse herself in technical studies, reports, and transcripts of nuclear-related proceedings. Belser suggested further readings to her, and she was an eager student.

Later in 1971 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that nuclear licensing procedures had to be in compliance with the National Environmental Policy Act of 1960. The earlier hearings about BNFP's construction license had not complied with that act. A few months after the Supreme Court decision, the AEC ruled that the Barnwell plant's license would have to be reconsidered under the new procedures.

For the first time, Belser saw an opportunity to challenge the plant with more than just a microphone and a magazine article. He helped Ruth Thomas and a handful of others set up an organization named Environmentalists Inc. (EI). Its primary purpose was to oppose AGNS's new request to build and operate the plant.

"There hadn't even been plans for public hearings," explains Thomas, "so first we had to force the AEC to hold hearings by making a public clamor." EI members spoke to groups and wrote letters to the local papers. They searched for allies both nationally and locally, and especially sought other South Carolina groups willing to intervene in the upcoming licensing hearings.

The state of South Carolina responded to the pressure and the arguments of Belser, Thomas, and others and set up a joint legislative committee to study the plant's expected economic and environmental impacts. Hearings were held in 1971 and 1972, and EI members participated by pointing out some of the problems of the Barnwell plant. They pushed committee members to tour a similar plant in West Valley, New York, which had operated — at a fraction of its capacity and with numerous radiation releases — from 1966 until it was forced to close in 1972. But that tour never took place, and AGNS officials were allowed to brief many of the committee's witnesses and even edited much of the final draft of the joint legislative committee's report. The report found that BNFP's economic impacts would all be beneficial, its environmental impacts insignificant.

EI continued its opposition and in May 1974 the AEC admitted the group to the next series of hearings on the plant's requests for construction and operating licenses. Two other small state groups were also admitted to the hearings, the Piedmont Organic Movement and the Hilton Head-based South Carolina Environmental Action Inc. Ruth Thomas represented all the participating groups, and Townsend Belser was hired as their attorney.

The two made a curious pair. "Townsend had the savvy and knew the engineering," explains Suzanne Rhodes, a former EI member. "And Ruth was just so persistent." With his broad background in nuclear science and the law, Belser identified the main areas at issue and methodically searched for weaknesses in the AGNS arguments. Thomas, a former art teacher, had no experience in either legal hearings or nuclear science. AGNS officials had sought to keep her out of the hearings because they felt, says Rhodes, that "she was just a housewife." She was often described as a "little old lady in tennis shoes."

"I had trouble doing everything that was required for the hearings," she admits, remembering the hearing which stretched from the fall of 1974 to January 1976. "But here are people sitting down and planning something that they know could kill people, that could hurt children, and they keep up with it. I was motivated beyond my potential," she says shaking her head. "I couldn't stand it, I was just so upset."

In preparation for the hearings, Belser put in 60-hour work-weeks and 40-to-50-hour weeks during the actual hearings. He billed the organizations at half his usual rate, but that was still far beyond the financial reach of the environmental groups involved. Thomas often attended the hearings by herself, while the industry and government were represented by a battery of experts with seemingly unlimited resources and information.

On retainer for AGNS was Bennett Boskey, a Washington attorney who had formerly served on the staff of the AEC. Since he wrote the licensing procedures that were being followed in the case, Boskey understood the rules and regulations of the hearings better than the licensing board itself, claims one EI volunteer lawyer.

In November 1975 the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, which had replaced the AEC, decided to go ahead and license the BNFP reprocessing facility on an interim basis. EI wearily joined the Natural Resources Defense Council, a national organization, and contested this decision before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second District.

There was far more work to be done than EI could handle. Adding to the difficulties, Belser withdrew as attorney for the Barnwell intervenors in May 1976. The small group owed him nearly $8,000.

EI had uncovered some information about the Barnwell plant's operation which rallied opposition. Among its findings: BNFP would release significant levels of radioactive effluents into the air; it would contaminate vast numbers of temporary workers should repairs ever be needed; and its design was a larger replica of the New York plant that had been shut down. In May 1976 EI got a boost when the appeals court overturned the government decision to license the Barnwell plant on an interim basis.

Civil Disobedience

By the end of the hearings in 1976, concern about nuclear power and its wastes had spread far beyond Townsend Belser and Ruth Thomas. A new group of activists had entered the scene, one whose style was significantly different from that of the conservative, middle-aged EI members.

On August 1, 1976, 18 New Hampshire residents marched onto the property of the Seabrook nuclear plant to protest its construction and, with 600 supporters rallying nearby, were arrested as trespassers. Three weeks later, 179 more were arrested at Seabrook as 1,200 rallied in protest. Among those arrested was a small group of South Carolinians, including one named Brett Bursey.

The son of a Marine Corps dentist, Bursey was known to South Carolina law enforcement people from an incident in March 1970, when he and four others were arrested for damaging property at the Selective Service office in Columbia. He was convicted and sentenced but he left town and went underground. Finally arrested in Texas a year later, he was returned to South Carolina and spent 18 months in state prison.

Bursey was a dynamic speaker with infectious enthusiasm. Part street-corner preacher, part rock-and- roller, he made political issues seem of immense importance and political action morally necessary, even fun. He attracted many followers as he argued that a group of people can change history.

In 1975, after his release from prison, he helped establish a political study group in Columbia, called the Grassroots Organizing Workshop (GROW), which took nuclear power as one of its concerns. Members of GROW turned to Ruth Thomas for information and assistance in their work.

By this time the outrage that Thomas had felt when she first heard Belser was shared by many others in the usually complacent state. South Carolina was becoming widely known as a major center of nuclear facilities and a national dumping ground of nuclear waste, and many residents were displeased. In 1975 four nuclear reactors operated there, and six others were planned. A low-level waste dump in Barnwell buried radioactive material from around the country, while SRP was one of the nation's largest nuclear weapons facilities. Perhaps most threatening, the Barnwell reprocessing plant seemed likely to open for business soon, either reprocessing or storing spent fuel.

Concern about nuclear power was so widespread that Bursey and GROW decided in 1977 to form the Palmetto Alliance, to focus state opposition to nuclear power. The Palmetto Alliance drew a new following of young people, many of whom had been involved in the anti-war movement. And just as the anti-war movement had burgeoned with enthusiasm, drawing in followers, so too did the anti-nuclear movement grow.

But the Palmetto Alliance took a more confrontational path than had EI, whose involvement in hearings and legal proceedings had actually done little to slow down the plant's construction schedule. The alliance members spent much of their first year planning an ambitious event in Barnwell. They intended to rally and demonstrate at the reprocessing plant, engage in civil disobedience, and if necessary be arrested. They invited nationally known musicians and speakers to appear as an added attraction for anti-nuclear demonstrators.

The Palmetto Alliance had no money and few supporters in the Barnwell area. The earlier civil rights and anti-war movements in South Carolina had never attempted an event of the scale Bursey and the alliance now planned. Many didn't think they could pull it off. They did.

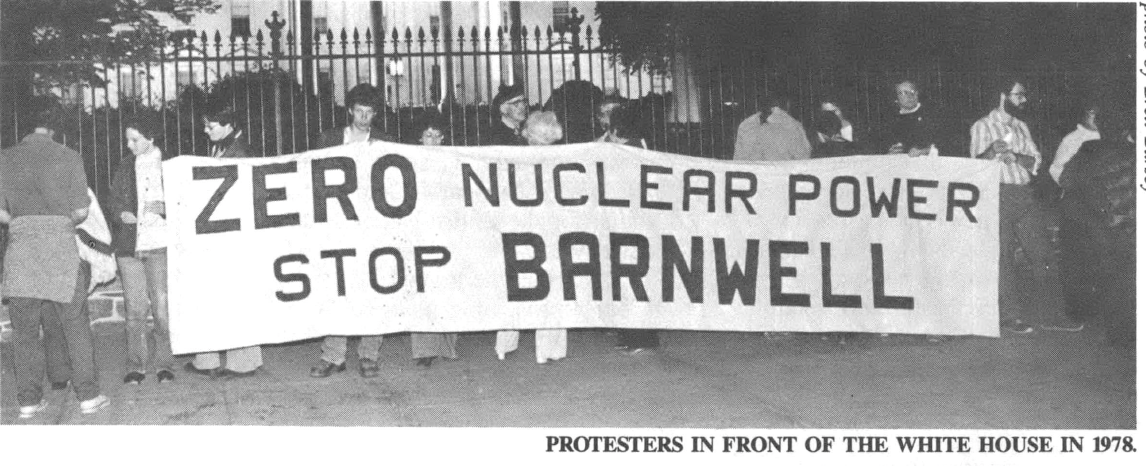

On April 30, 1978, 2,000 people from a score of Southern groups marched by the plant and rallied in a nearby cornfield. Grace Laitala, a 66-year-old woman from Clemson, presented AGNS officials with a petition bearing 10,000 signatures, asking the industry to stop nuclear waste dumping. Laitala's presence, along with that of several Barnwell-area farmers, suggested that anger toward the plant crossed many age and class barriers. She and her 69-year-old husband Everett, a retired professor of industrial engineering, appeared at a press conference where Grace Laitala told reporters, "We're straight people, real straight. We believe in apple pie and staying married and stopping nukes.''

The next day the Laitalas were among the 280 people who huddled under a plastic tarp on AGNS property while a mighty rainstorm beat down. When the rain stopped, they were arrested.

The rally and arrests made national news and dramatically alerted South Carolinians to the controversy surrounding the plant as two years of hearings had failed to do. The Palmetto Alliance spent about $37,000 on the event, despite the fact that few staff people received any money. To help pay the bills, Bursey borrowed about $6,000 from Northern supporters. The entire Palmetto Alliance was responsible for that debt, but Bursey had personally made most of the decisions about the organization of the event and about money.

In the aftermath of the Barnwell action, rumblings of resentment against Bursey grew to a roar. Some claimed his radical reputation limited the ability of the group to gain support. Throughout the state movement, Bursey himself became a major issue.

In the year following the Barnwell action, Palmetto Alliance followers separated themselves from Bursey. They moved out of the GROW building — a ramshackle office above a bar and grill, the GROW Cafe, in a low-income neighborhood — and into a more modem office. Three staffpeople were hired — Ted Harris, who had driven Bursey to Seabrook years before; Michael Lowe, a former construction worker at a nuclear plant; and Bebe Verdery, after Ruth Thomas only the second woman to play a leading role in the state's antinuclear organizations.

They soon began helping a group called the Natural Guard to prepare for an event to be called Barnwell II. It would be another mass demonstration, to coincide with similar actions around the country on September 30 and October 1, 1979.

Again speakers and musicians addressed a crowd in a cornfield on the dangers of nuclear power, but now the focus was on all three local facilities: the Barnwell low-level waste dump, the Savannah River Plant weapons facility, and BNFP. This time 1,200 people participated in the rally and 161 were arrested. No longer unique, such events still attracted major news coverage.

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter banned the reprocessing of nuclear wastes in an effort to limit the world supply of bomb-grade plutonium. All of the hearings on BNFP's future were cancelled.

Dick Riley, a liberal state senator from Greenville who was running for governor, visited the Palmetto Alliance office in 1978 when it was still located in the GROW building, and spent three hours discussing nuclear power with Ted Harris. Riley won the election and was in power when, in March 1979, a truck loaded with nuclear waste from Pennsylvania's crippled Three Mile Island reactor set off for South Carolina. Governor Riley boldly turned it away, announcing, "South Carolina can no longer be the path of least resistance in seeking the national answer to nuclear waste disposal."

At the time of Riley's election, South Carolina shouldered a major portion of the nation's nuclear waste burden. In 1979 the waste dump in Barnwell, next door to BNFP, buried 85 percent of the nation's low-level waste. Riley didn't oppose nuclear power, but he argued for a more equitable distribution of the responsibility for handling it.

Eventually other South Carolina politicians also spoke out against the spread of nuclear technology, hearing increasingly widespread complaints from constituents about the state's role in the business. By the early 1980s, saying "no" to nuclear facilities had become a mainstream position.

The plant's economic foundations were also eroding by this time. Even before the Three Mile Island accident, utilities had stopped ordering nuclear reactors. A limited number of reactors meant a limited amount of spent fuel available for reprocessing. Besides, reprocessed fuel would be financially attractive only if the price of uranium soared, and that wasn't happening.

BNFP was also experiencing cost overruns. It was originally priced at $70 million, but the owners had upped their cost estimates to nearly $1 billion. Opponents of the plant also learned that in 1975 AGNS had asked the federal government to join it in a "cooperative program" of construction and demonstration.

Belser and Thomas considered this request an acknowledgment that AGNS could not afford to complete the plant. By the late 1970s, Belser and Thomas had been relegated to the background of the state's antinuclear movement. Belser chose his own exile, moving to Washington, D.C., a city with considerably more work for a patent attorney than Columbia, South Carolina. The move also allowed him to remove himself from the exhausting fight against BNFP — "Burnout," he says curtly.

Thomas remained in Columbia, still fervently and actively opposed to nuclear power. But she was out of the movement's mainstream. The AGNS hearings, temporarily suspended in 1976, were never resumed. And while Thomas welcomed the appearance of a new generation of activists, she was rarely asked to join them. Part of her isolation may be due to the feeling of some former colleagues that she is disorganized or difficult to work with. But Suzanne Rhodes points to another reason for Thomas's exclusion from the young, mostly male, movement: "her age, her sex."

Victory, For Now

While years of hearings produced damning information, and the speeches and rallies helped change public opinion, politics and economics finally killed the AGNS reprocessing plant in 1983. Though Ronald Reagan reversed Carter's ban on reprocessing early in his administration, he was unwilling to lobby Congress to pay the bills for the plant's completion and operation. AGNS, claiming it feared another government policy reversal, refused to invest further in the plant. Other companies expressed interest in buying it but never came up with the necessary money. Between 1978 and 1982, while AGNS officials scrambled in search of a buyer, the plant's staff was held together by $75 million in government research funds. And AGNS lobbyists repeatedly returned to Congress asking for one last year of funding. Eventually even Congress balked.

Beginning in 1981, South Carolina Congressman Butler Derrick led an effort in the House to eliminate federal funding. A decade earlier, he had been alerted to the problems at Barnwell by his friend Townsend Belser. In 1983 Congress finally said no more, and government funding for research at the Barnwell Nuclear Fuel Plant ran out on July 31, 1983.

Some private companies, primarily The Bechtel Group, continue to express interest in taking over the plant. AGNS spokesman George Stribling still says, "We believe it'll come back." For now the opponents of the plant have scored a major victory. But they've hardly had time to celebrate.

Ruth Thomas is busy following a broad spectrum of energy issues, providing the public and media with background information on everything from radiation releases to rate hike requests. Brett Bursey is organizing people around disarmament and American adventurism abroad.

Of the three Palmetto Alliance staffpeople from the post-Bursey days, Michael Lowe remains as director, busy with the licensing hearing for the Duke Power Company Catawba I reactor in Rock Hill, South Carolina. Bebe Verdery works on disarmament issues, Ted Harris in an intervention opposing government plans to reopen a Savannah River Plant reactor that has been closed since 1968.

These people, and thousands more, challenged a multi-billion-dollar industry that was supported by the most powerful people in the state and nation. They challenged it in government hearings, in debates, in the media, and in the halls of Congress. "I was impressed," Belser says now, "to see that a dedicated individual in this country could make a difference. I was shocked by the size of the difference."

Tags

Steve Hoffius

Stephen Hoffius is a free-lance writer in Charleston, South Carolina. For a year he edited the state newsletter of the Palmetto Alliance. (1984)

Steve Hoffius is a free-lance writer in Charleston, and a frequent contributor to Southern Exposure. (1979)

Steve Hoffius is a Charleston, SC, bookseller and free-lance writer. (1977)

Steve Hoffius, now living in Durham, N.C., co-edited Carologue: access to north carolina and is on the staff of Southern Voices. (1975)