Beyond the White Columns: A Fresh Look at Painting in the South

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 3, "Painting South." Find more from that issue here.

Our big museums, like our high courts, move with ponderous slowness, ratifying the status quo or gingerly exploring controversial territory.

A museum director, like a judge, hates to get too far ahead of establishment values or fall too far behind; both preside over innately conservative institutions. For this reason, major exhibitions and their catalogues, like milestone court cases and their accompanying arguments, often provide an index of how far the powers-that-be have, or have not, come.

An important show, like a Supreme Court decision, can also steer debate, sanction fresh evidence, offer novel interpretations, and establish new precedents. And just as some legal verdicts prompt immediate explosions and others take time to be deciphered, certain museum displays are openly controversial while others reveal their full import only gradually.

I suspect the current traveling exhibition entitled "Painting in the South: 1564-1980," organized by the Virginia Museum, may eventually be recognized as something of a cultural landmark for the region, but the exhibition's first viewers found it a bit confusing. "In contrast to the Northeast," points out project director Ella-Prince Knox, "there is little public information about the painting traditions of the South."

The display of more than 150 works seemed unfamiliar and disconcerting to members of Richmond's upper crust who attended the gala opening last September. Wine glasses in hand, they squinted at miniature portraits and stepped back from enormous modem canvases, here and there noting a familiar artist such as Audubon. Perhaps too many were expecting a nostalgic portrayal of the South or an expansion of a show at Washington's Corcoran Gallery in 1960 called "American Painters of the South."

That exhibit highlighted Baltimore, Washington, Richmond, and Charleston, and focused on the plantation years between 1710 and 1865. Surely no one produced much "Southern Art" beyond the Piedmont or after Appomattox, many viewers must have reasoned, so shouldn't this new exhibition in the "Capital of the Confederacy" be a grander version of the previous show? After all, the cover of the Corcoran catalogue used Eastman Johnson's seemingly folksy portrayal of slavery known as My Old Kentucky Home — Life in the South, and the current catalogue cover features a slice of ripe watermelon on a black background from an 1820 still life by Sarah Miriam Peale. No wonder guests were expecting mint juleps.

But no one who opens the book or enters the exhibit sees much of Tara, for Margaret Mitchell did not put together this display. Instead, an unusual team of five scholar-curators drafted the chronological essays and selected the array of pictures now on tour. Their exhibit has already given museum-goers in Richmond and Birmingham something to think about, and it should reward and surprise anyone who finds the time to stroll through it later this year (see schedule, page 42) or to browse at leisure in the costly but definitive catalogue. Carolyn Weekley, Linda Simmons, Jessie Poesch, Rick Stewart, and Donald Kuspit, all national authorities on American art, spent several years on this project, and it reflects their impressive collective knowledge. It also reflects how the region's dominant self-image has shifted in the past two dozen years.

The guest curators invoke a wide-open definition of the people and places that have made up "painting in the South." They have declared the region's lively folk painting traditions off-limits.* And they have ruled out travel sketches, photographs, and the works of Southerners, such as Washington Allston, who went away to paint. But they have made room for Northerners who came south, including such well-known figures as Samuel F.B. Morse, Winslow Homer, Edward Hopper, and the members of the Black Mountain School. Just as the "southern light" of the Mediterranean has traditionally appealed to European artists, the luminous quality of the Deep South atmosphere has long attracted American painters.

More importantly, the curators have finally made space for the whole Southern landscape. While the familiar artists of the Atlantic seaboard still get their due, the less familiar painters of the Gulf Coast and the interior are highlighted for the first time, particularly in Jessie Poesch's essay on the South from 1830 to 1900. She explores Louisiana's French connection, as in Hippolyte Sebron's Giant Steamboats at New Orleans, and the movement from east to west, as in View of Galveston Harbor by Charlestonian William Aiken Walker.

Chincoteague ponies are balanced against east Texas dairy cattle. Alongside Virginia's Dismal Swamp and Natural Bridge appear north Georgia's Tallulah Falls and sunset scenes from Florida and Tennessee. An antebellum painting of elegant Oakland House and Race Course, Louisville, Kentucky contrasts with later pictures of a Trapper's Cabin on the Mississippi Delta, a Bayou Farm near Lake Pontchartrain, and the jacal of a Mexican girl near San Antonio. In one portrait from 1858 an "independent squire" named Jack Porter relaxes on his rustic porch in Frostburg, Maryland; in another from the same year Colonel and Mrs. James A. Whiteside pose surrealistically overlooking the Tennessee River at Moccasin Bend.

No single spot has been scrutinized more closely by an artist in recent years than the islands and shoreline near Ocean Springs, Mississippi. There, New Orleans native Walter Inglis Anderson lived to the age of 62. After his death in 1965, family and friends found that his remote cottage was literally strewn with colorful and vivid nature paintings on scraps of typing paper and even on the walls themselves. A small watercolor of crabs, entitled Horn Island, illustrates the intensity with which this Southern Thoreau communed with nature along his narrow strip of Gulf Coast. (See the feature on his work in Southern Exposure, Vol. X, No. 3, May/June, 1982.)

During our own generation, a sense of motion has augmented a sense of place. The South's modern painters are drawn to railroads as frequently as the region's musicians — sometimes even to the same section of track. (For example, in 1965 Arkansas native Carroll Cloar created Where the Southern Cross the Yellow Dog, a radiant orange landscape of the crossing at Moorhead, Mississippi, immortalized in the jazz of W.C. Handy.) Of course the region's artists are drawn to all kinds of roadways as well, from the hazy four-lane in Victor Higgins's Pilot Mountain to the wet Florida straightaway of Martin Hoffman's Open Road. Blue Sky, whose highway wall murals enliven his home town of Columbia, South Carolina, and other Southern cities, is represented by Air Brakes, a mixed-media rendering of a trailer truck's rear end. The show's most recent picture, K. C. Suzuki (1982), reflects the biking fascination of Alabama artist David Parrish, whose father used to tour the region by motorcycle with a circus.

Nothing emphasizes the country road as the direct route to the soul of the South more clearly than the exhibit's largest — and perhaps most central — work, entitled Symbols (1971). Benny Andrews was bom to a sharecropper family in Madison, Georgia, in 1930, and his stark 37-foot allegory is an Ellison-like comment on the theme of invisibility as determined by race and riches. Eleven panels wrap like a windshield around the viewers, who find themselves heading down a road as startling as Dorothy's in The Wizard of Oz. The huge oil-and-collage is owned by Wichita State University, but this certainly isn't Kansas!

Beyond the varied landscape are the people, and not surprisingly many painters and sitters included in this Southern gathering turn out to be related. Viewers raised to hunt genealogical ties will spot frequent bonds of kinship. In colonial South Carolina, miniaturist Mary Roberts was married to Bishop Roberts, who created a vivid prospect of Charleston at the time of the Stono Rebellion. Rachel Moore of that town, who posed for Henry Benbridge on the eve of the Revolution, was the mother of Washington Allston; Mrs. Leonard Wiltz, who sat for female portraitist L. Sotta in New Orleans in 1841, was the mother of artist Leonard Wiltz, Jr. In Civil War Virginia, Conrad Wise Chapman was the son of Alexandria painter John Gadsby Chapman. Among early twentieth-century artists, the Onderdonks from east Texas are father and son, while Ellsworth and William Woodward in Louisiana are brothers. With Maryland's remarkable Peales such links approach the absurd; works by five members of the family appear in the exhibit, and two other relatives are cited in the catalogue.

But the same show that proves Southern painting has existed beyond East Coast cultural centers also demonstrates that painting in the South has never been the sole province of an ingrown elite. In a society that discriminated from its inception in favor of well-to-do Caucasian males, you would expect such men to dominate any retrospective survey of the region's most exclusive art form. But they do not. They are matched at every turn, on both sides of the easel, by a variety of other Southerners who nearly steal the show.

Though Boston's Museum of Fine Arts omitted black artist Henry Tanner from its recent exhibit of American Masters until pushed to include him, the curators of the Richmond display needed no such prompting. They include a handsome family portrait from 1818 by Joshua Johnston of Baltimore and a little-known depiction of a Louisiana black woman, apparently by another "free person of color" named Jules (or Julien) Hudson.

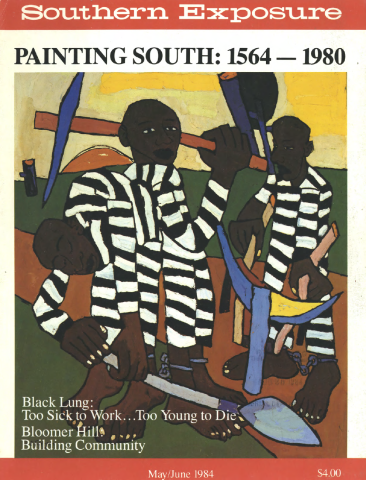

Several famous twentieth-century black artists are represented, such as Romare Bearden, born in Charlotte in 1914, and Aaron Douglas, who taught at Fisk for nearly 30 years. So are less widely known artists, such as Georgian Benny Andrews and South Carolinian William H. Johnson (1901-1970). The striking picture Chain Gang (painted after Johnson's own arrest in his home town of Florence during the 1930s) illustrates the original blend of European and African influences, plus the strong personal vision, that characterize this brilliant Southern painter.

Women artists are also well represented. The pastel portraits of Henrietta Johnston, who died in Charleston in the 1720s, have long been to Colonial painting what Anne Bradstreet's poems are to early American literature. But many of Johnston's modem successors are less celebrated, such as Mississippi art teacher Marie Hull, Georgia seamstress Willie Chambers, and South Carolina local colorist Alice Ravenel Huger Smith.

When Clara Weaver Parrish from Selma, Alabama, was earning international recognition at the turn of the century, she painted a revealing portrait of the wide-eyed and intense young feminist Anne Goldthwaite, who had recently arrived in New York from Montgomery to pursue a career in painting. Many of Goldthwaite's later pictures, such as Springtime in Alabama, drew on the world she knew best. Another Montgomery woman, Zelda Sayre, took up painting shortly after she married writer F. Scott Fitzgerald in 1920. The story of their trying marriage has often overshadowed her creative bent, but Zelda Fitzgerald painted revealing personal pictures until her tragic death in 1948.

On the other side of the easel, the social diversity is more striking still. The curators remind us that the same artists who have always seen the region's geographic variety have also had eyes open to its social diversity. The exhibit downplays heroic portraits of traditional icons. John Trumbull's painting of George Washington, owned by the city of Charleston, is included only in the catalogue.

Limner Charles Peale Polk, who earned much of his living selling likenesses of Washington, is represented instead by a curious and slightly unflattering portrait of Jefferson. Rembrandt Peale, who also painted Washington, is introduced through an impressive picture of fellow artist Benjamin Henry Latrobe. John Adams Elder, an aide in the Confederate Army best known for his portraits of Lee and Jackson, is featured through a genre painting of the interior of a sharecropper's cabin.

Where previous exhibits have ignored Native Americans entirely or given them only a textbook nod through such pictures as the English portrait of Pocahontas in Washington's National Portrait Gallery, this display begins to take fuller notice of the first Southerners. The extraordinary water colors by Jacques Le Moyne and John White that survive from the lost French and English colonies of the pre-Jamestown era are now too delicate to travel, but they appear in color in the catalogue.

Several nineteenth-century artists became famous painting Indians, many of them from Southern tribes. George Catlin visited Seminole prisoners at Charleston's Fort Moultrie, creating a dignified portrait of the military leader Osceola and a less striking picture (included in the exhibit) of the "first chief' of the Seminoles, Mick-e-no-pah. Also included is Mistipee, a young Creek painted by Charles Bird King in the somewhat precious and romantic style that appealed to the establishment in the era of Indian Removal.

More intriguing is an earlier painting entitled William Bowles and the Creek Indians (circa 1800), in which a white gentleman encourages several Indians to "take up the plow." The flamboyant Bowles lived among the Creeks for two decades after the Revolution and probably created this optimistic and self-serving image of assimilation. The exhibit's most suggestive view of Native Americans was painted by Alfred Boisseau at the age of 24. In 1847 the young Frenchman, whose brother worked at the French consulate in New Orleans, executed a somber group portrait called Louisiana Indians Walking Along a Bayou. The procession includes a father carrying a long rifle, a boy with a traditional blowgun, a woman carrying a heavy load, and a second woman with a small child on her back.

Women, single and in groups, white and nonwhite, of all classes and ages, inhabit the exhibition. Shortly before he died in the yellow fever epidemic of 1796, James Earl painted a prominent Charleston lady and her niece. A generation later Englishman William James Hubbard portrayed the daughters of Richmond's mayor in a similar double portrait. These staid young ladies make an interesting contrast to the motley gathering of children in Alexander Brook's Savannah Street Comer, painted near the end of the Great Depression, or the girl on a swing, soaring through dappled summer foliage in a 1981 picture by Maude Gatewood of Yanceyville, North Carolina.

Again, two of the exhibit's most impressive "discoveries" come from European-born artists working in nineteenth-century Louisiana. The Frenchman Jean Joseph Vaudechamp visited New Orleans every winter during the 1830s, and his painting of A Creole Lady is a handsome portrayal of an unglamorized and impressive local citizen. The same can be said for another possession of the New Orleans Museum, Francois Fleischbein's Portrait of Marie LeVeau's Daughter from the 1860s. Whether the self-possessed mulatto woman who posed for the Bavarian-born artist was in fact the legendary "voodoo queen," or her daughter, or someone else entirely, she is one of the most memorable and dignified personages in the exhibition.

The significant place of blacks in the life and art of the South can be read from the exhibit's canvases, beginning with the work of an immigrant portraitist, Justus Engelhardt Kuhn, at the start of the eighteenth century. Kuhn's likeness of young Henry Darnall III and his servant, painted in Annapolis just as the slave trade from Africa began to expand (and a half-century before Kunte Kinte reached the same port), is one of the earliest American works to depict an African. The image combines the European tradition of "the black page" with the harsh realities of Chesapeake slav-

ery, for little Damall's young chattel is wearing the metal collar of a pet and is obliged to fetch the white boy's game bird like an obedient field dog. (Exactly such a dog can be seen in William Dering's Williamsburg portrait of George Booth as a Young Man from the 1740s.)

Black figures are almost as numerous as white in the exhibition's nineteenth-century pictures, and they actually predominate in the paintings chosen from the present century. Some are sympathetic versions of stereotypic scenes, such as John Kelly Fitzpatrick's colorful 1931 composition of a Negro Baptising in Alabama or Julien Binford's high-rolling Crapshooter from Fine Creek, Virginia, which won a national award from Chicago's Art Institute in 1941. Others impart particular artistry to everyday rural scenes — such as Howard Cook's print-like sketch of Alabama Cotton Pickers and Robert Gwathmey's stark and inspired Hoeing — or to urban scenes for that matter, as in William Woodward's Old Mattress Factory in the French Quarter of New Orleans and Alexander Brook's Georgia Jungle on the outskirts of Savannah.

If viewers are surprised that the Virginia display defines the South and its people more expansively than previous exhibits of the region's high art, they will be equally struck by the muted and reflective presentation of the "Lost Cause" of the Confederacy. There are no Civil War battle scenes or portraits of Southern commanders. Robert E. Lee himself is absent from the collection, and he appears in the catalogue only in an 1838 likeness of the young officer in federal uniform by Kentucky artist William Edward West. The one Confederate icon on display is William D. Washington's Burial of Latane (1864), widely distributed as a sentimental engraving after the war. It can be juxtaposed to the larger and less famous work of John Antrobus, A Plantation Burial (1860), which focuses on a black funeral in Louisiana and reduces non-slaves to minor figures.

Glimpses of the war itself come not through any monumental canvases, but through a series of small-scale and ruminative oils. Conrad Wise Chapman, a painter-tumed-Confederate-soldier like Washington and Antrobus, was wounded at Shiloh and later sketched the fortifications at Charleston after his convalescence. His small, clear studies of the harbor batteries and the inhabited ruins of Fort Sumter are fresh and unromantic. (Unfortunately, a comparable little painting of the Byrds' famous Westover mansion in wartime by Charleston-born Edward Lamson Henry, who grew up in the North and served in Grant's army, appeared only in Richmond and is not traveling with the show.)

Along with centennial observances of the Confederate years, the early 1960s brought a new civil war to the South, and the ironies were not lost on discerning artists. In 1961 Larry Rivers, one of the boldest "history painters" of the generation, created The Last Civil War Veteran. Much as contemporaries once read their own meanings into Eastman Johnson's ambiguous Life in the South, modem viewers can draw conflicting conclusions from Rivers's picture. A superannuated soldier lies propped against pillows beneath Confederate and American flags, while his century-old uniform hangs above the bedside. Is he a diehard rebel refusing to surrender, still hoping in death to stir a resurrection of the Lost Cause? Or is he a healer who may, dying a hundred years after many of his colleagues, bring peace and reconciliation to a house so long divided?

A less blatant but equally challenging image was created two years later by Francis Speight, born in Windsor, North Carolina, in 1896 and still residing and painting in Greenville. His Demolition of Avoca shows the plantation home of a Confederate surgeon near Albemarle Sound being torn down so its owners, the R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company, can construct an experimental plant. Each viewer must decide just how handsome and significant the original structure, with its spindly columns, may have been. Was Avoca's (and the Old South's) battered condition in 1963 disheartening or overdue, a result of internal rot and fires or outside wreckers? Would the new structures on a changing landscape be a cause for celebration?

Picture exhibits, like court decisions, are never final and definitive; they always generate as many questions as they answer. And they do not always offer simple viewing, any more than judicial verdicts promise easy reading. But those who take time to peruse the Virginia Museum's traveling show as if it were a complicated legal case will find that it begins to affirm, however tentatively, a broader definition of the South's regional heritage. It establishes useful precedents and suggests new lines of inquiry in the ongoing process of cultural self-discovery.

* See instead the catalogue of a recent Corcoran Gallery exhibition: Jane Livingston and John Beardsley, Black Folk Art in America, 1930-1980 (Jackson, Mississippi, 1980), and the catalogue of an exhibit now at Chicago's Field Museum through December 1984, African and Afro-American Art: Call and Response (Chicago, 1984).

Tags

Peter H. Wood

Peter H. Wood is an emeritus professor of history at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. He is co-author of the U.S. history survey text, "Created Equal," now in its fifth edition.