The Making of a Woman Suffragist

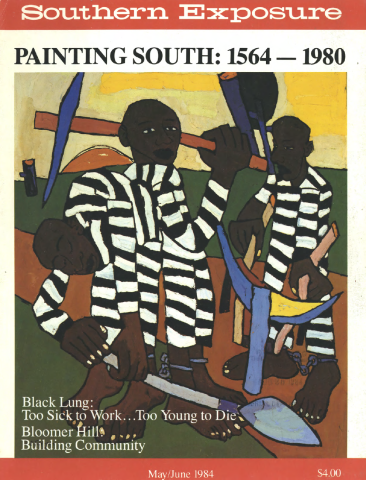

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 3, "Painting South." Find more from that issue here.

Belle Kearney was a Mississippi woman active in the Women's Christian Temperance Union. In 1900 she published her autobiography, A Slaveholder's Daughter (St. Louis: The St. Louis Christian Advocate Press, 1900), in which she explained how she came to be a strong advocate of the right to vote for women. The following excerpt can also be found in One Half the People: The Fight for Woman Suffrage, edited by Anne F. Scott and Andrew M. Scott (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1975).

The freedom of my home environment was perfect, but I recognized the fact that there were tremendous limitations of my "personal liberty" outside the family circle. An instance of it soon painfully impressed my consciousness. Three of my brothers, the comrades of my childhood, had become voting citizens. They were manly and generous enough to sympathize with my ballotless condition, but it was the source of many jokes at my expense among them. On a certain election day in November, they mounted their horses and started for the polls. I stood watching them as they rode off in the splendor of their youth and strength. I was full of love and pride for them, but was feeling keenly the disgrace of being a disfranchised mortal, simply on account of having been born a woman, — and that by no volition of my own. Surmising the storm that was raging in my heart, my second brother — looking at me, smiling and lifting his hat in mock courtesy said: "Good morning, sister. You taught us and trained us in the way we should go. You gave us money from your hard earnings, and helped us to get a start in the world. You are interested infinitely more in good government and understand politics a thousand times better than we, but it is election day and we leave you at home with the idiots and Indians, incapables, paupers, lunatics, criminals and the other women that the authorities in this nation do not deem it proper to trust with the ballot; while we, lordly men, march to the polls and express our opinions in a way that counts."

There was the echo of a general laugh as they rode away. A salute was waved to them and a good-by smiled in return; but my lips were trembling and my eyes were dim with tears. For the first time the fact was apparent that a wide gulf stretched between my brothers and me; that there was a plane, called political equality, upon which we could not stand together. We had the same home, the same parents, the same faculties, the same general outlook. We had loved the same things and striven for the same ends and had been equals in all respects. Now I was set aside as inferior, inadequate for citizenship, not because of inferior quality or achievement but by an arbitrary discrimination that seemed as unjust as it was unwise. I too had to live under the laws; then why was it not equally my interest and privilege, to elect the officers who were to make and execute them? I was a human being and a citizen, and a self-supporting, producing citizen, yet my government took no cognizance of me except to set me aside with the unworthy and the incapable for whom the state was forced to provide.

That experience made me a woman suffragist, avowed and uncompromising. Deep down in my heart a vow was made that day that never should satisfaction come to me until by personal effort I had helped to put the ballot into the hands of woman. It became the mastering purpose of my life.

Tags

Belle Kearney

Belle Kearney was a Mississippi woman active in the Women's Christian Temperance Union. In 1900 she published her autobiography, A Slaveholder's Daughter (St. Louis: The St. Louis Christian Advocate Press, 1900), in which she explained how she came to be a strong advocate of the right to vote for women. (1984)