This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 12 No. 3, "Painting South." Find more from that issue here.

I first noticed the symptoms of black lung in my own body; it was in about 1968. I noticed the shortness of breath, I noticed the wheezing. I could be in one end of the house and my wife in the other, and she could hear me wheezing.

In a sense it’s a humiliating disease, in that a man loses a sense of his manliness. It’s when you can’t do what you like to do, that’s humiliating. I had to lay down my hammer and saw, and those were the things I got the most pleasure out of. The next thing I liked to do was work in my garden; now my garden’s the biggest weed patch in Logan County. There were times in 1971 when I was still working that it was difficult for me to get to the bedroom when I was feeling bad. Now, of course, that’s humiliating.

— Willie Anderson

For well over a century, since the first large-scale coal mining in the United States, miners have gone to early graves with black lung disease. Physicians traditionally reassured their coal miner patients that they had a benign “miners’ asthma,” and suggested that their strangling symptoms of lung disease were due to a liking for alcohol, a dislike of hard work, or perhaps “fear of the mines.” Yet there exists virtually no Appalachian hollow or coal town without at least one miner suffering from black lung.

In 1968, in West Virginia this contradiction erupted into a powerful movement, as the generation of coal miners exposed to the especially dusty mechanized workplaces of the post World War II period reached the end of their working lives. Facing retirement, these miners could look forward at best to a scanty pension of $115 per month — if they were fortunate enough to qualify — and daily activities increasingly limited by their struggle to breathe. In West Virginia, Tennessee, Kentucky, and most other coal-producing states, their occupational respiratory disease was not medically or legally recognized, so most were denied workers’ compensation benefits.

Unaware of the tremendous upheaval their actions would set in motion, a few local union activists in southern West Virginia began to organize small meetings about black lung in the fall of1968 They were opposed not only by the companies, but by the medical establishment and by a corrupt union hierarchy as well. But they also found support — initially from three sympathetic physicians, a handful of VISTA workers, and liberal reporters from the local and national media. Many others were converted to the miners’ cause overnight, when the Consolidation Coal Company’s massive Farmington No. 9 mine exploded on November 20,1968, killing 78people. Joe Malay was one of the early leaders:

Old Dr. [I.E.] Buff, he was doing stuff on black lung. So we wrote him a letter and he said, “You just name the time.” I wrote to about 20 locals and I got one local to come. That was old Woody Mullins’s, down here at Gallagher. Ten, maybe 12 people at the first meeting. These people here in District 29, they was scared to death. They was afraid of the union. They saw no one got shot, so they started coming.

Woody Mullins listened to Dr. Buff and said, “Would you come to my local and explain it?” We told Dr. Buff we’d try to get a better audience. So we invited Dr. [Donald] Rasmussen and a few other locals. But still, those first two meetings, 25 would have covered it.

A political strategy soon emerged from these meetings: the miners would wage a legislative battle for the recognition of black lung as a compensable disease under West Virginia’s workers’ compensation laws. Pursuing a legislative strategy without union endorsement required going to the general public in a bid for political support and funds to pay a lawyer to draft legislation. If they failed, the movement’s leaders would be marked as troublemakers; retaliation from employers and union higher-ups could be severe. Ed Blankenship (pseudonym) was still working in the mines in 1968, and remembers those fears well:

Well, the first thing I heard about — they gave me a call they was going to have a meeting over in Montgomery, over at city hall. We had a meeting over there — about 15 or 20 of us. Everyone was afraid they was going to get fired. We needed $3, $4, $5,000 on Monday morning to pay the lawyer. I don’t remember how much, but nobody had it. The main thing they was worrying about, the men was worried the company would come down on them, fire them.

Despite their fears and uncertainty, these few individuals decided to form a Black Lung Association to organize miners, spur community support, and provide a way to raise funds. Woodrow Mullins was one of the founding members:

We started the West Virginia Black Lung Association [BLA]. We had to raise money for Paul Kaufman, the lawyer. Some were afraid we just couldn’t raise the money. So we got down on the street [in Montgomery] — Charles Brooks and myself and Lyman Calhoun and a few others. We stopped on the comer and we said we could not be defeated. If we had to sell peanuts on the comer, we had to raise that money.

Charles Brooks [a black man who was the first president of the BLA] put up his house to get money for the lawyer. And we went around to locals. My local, they donated $1,000. Arnold Miller’s local, they gave $1,000. Lyman Calhoun’s local gave $500. Then others gave $100, $200, $300, like that.

We fixed up a table down there at the capitol. Dr. Rasmussen gave us a bunch of lungs. We just stayed in the capitol and lobbied, when we could. I borrowed a casket off an undertaker at Marmet; we put it in the capitol to show how many people, so many people were dying with it.

As a movement initiated by local union activists around a workplace issue, the first participants were all men, all members of the United Mine Workers of America [UMWA]. However, soon after the BLA became a community organization distinct from the union, meetings became public events and participation broadened. Leona Hall became a leader of the movement in her area:

In 1969, women wasn’t going to as many things as they are now. When they formed the Black Lung Association out at Montgomery, it was all men. So Mr. Calhoun used to report in to me, call me and tell me all about what took place. See, Mr. Calhoun’s wife was a cousin to my husband, and he worked with Mr. Calhoun at Bumwell, up on the creek. One day, Mr. Calhoun said, “Why don’t you come to the meeting yourself?” I said, “I can’t go, I can’t go up there. That’s just a bunch of men. No women comes.” And he said, “Well, Mrs. Malay comes.” So his wife and Mr. Mullins’ wife and Mr. Sturgill’s wife and me all started going.

Throughout the winter of 1968-69, black lung rallies in the coal camps of southern West Virginia grew in size and exuberance. Every weekend, miners, miners’ wives, and widows met in churches, schools, local union halls, and — when there wasn’t a place large enough to accommodate them — out of doors in the snow. The main attraction was usually a “real dog and pony show” put on by the physicians, who would bring along a set of real lungs from a victim of black lung. Clara Cody remembers the impression the doctors’ performances made:

We would open with a prayer. Buff would take them lungs and act…well, he went a bit too far sometimes. It’s like this, you see, very few people ever saw a set of lungs. He told the men about the bad lungs and he’d yell, “Feel ’em! Feel ’em!”

The rallies galvanized the spirit of unity and promoted the belief that people were entitled to redress for the injustices they had endured, as Mildred Mullins recalls:

I probably was fighting mad. ’Cause, you know what got me, you’d go to these rallies, there’d be these old men there, much older than my husband, couldn’t get no breath at all. You’d think they’d go through the ceiling trying to get air. Before they’d get done telling you how dirty they’d been done, they’d be crying. Didn’t get no pension, didn’t have no hospital card, didn’t have nothing to live on. Now, that gets next to you. It still makes me mad when I think about it.

THE BLACK LUNG STRIKE

By mid-February 1969, the West Virginia legislature was more than halfway through its session, and the BLA-drafted legislation remained stuck in the House Judiciary Committee, as did other related bills. The BLA activists became increasingly restless and concerned about the fate of their efforts. Joe Malay:

We tried going down to the legislature, lobbying down there, but Lord, you try to work all day and then drive to Charleston. You can’t do it. But the coal operators, they was living down there, you know, their lobbyists were. So we just called a big strike. We just quit. Winding Gulf was the first that came out. They had some grievance they struck over. So, maybe to keep ’em from being fired, they said they were striking over black lung. That thing just steamrolled.

The wildcat strike spread quickly through the web of local unions across the state, and within three days, 10,000 miners were on strike. Earl Stafford is a fourth-generation coal miner who became a leader of the movement:

I went and picketed my mine and others went and picketed theirs. I come and talked to the president of my local and he called the presidents of other locals. He told the men what it was all about. ’Course, we had gotten it on the news so it was well known. So we went over to Itmann, over there to Boone County, Kanawha County, all over. If nothing else, we’d go up there, go to the mine and get with one man, whether we knew him or not, and explain it to him. And he’d say, “Okay, you boys go back to Mingo County or wherever you belong, and we’ll take care of it here.” The next day all the mines over there would be out.

Opposing the movement was an array of political powerhouses. Craig Robinson, a VISTA worker in southern West Virginia, recounts the coal operators’ reaction:

The operators didn’t want any change at all. They took the position that it was “galloping socialism.” They definitely didn’t want to pay people who had already been injured; they said it was unconstitutional. They said the real epidemic wasn’t black lung, that there is a lung disease epidemic, but it’s not caused by coal dust. It’s caused by smoking and pollution.

Accustomed to calling all the shots within the union, district and international union officials also viewed the rank-and-file upsurge as a threat to their power. Joe Malay:

The district over here and the one in Charleston, District 17, they began fighting us. They were working against us. They called us communists; they said we was tearing the union up. Even in the mines they made fun of us. Thought we couldn’t get anything, thought we’d gone crazy.

The leaders of the BLA did not publicly criticize their union officials. They stuck to the black lung issue and allowed UMWA president Tony Boyle to condemn himself by opposing an exceedingly popular cause.

About a week into the strike, in late February, a major rally in Charleston, the state capital, drew together the movement’s supporters from around West Virginia. Three doctors — Buff, Rasmussen, and Hawey Wells — were joined on the podium by Congressman Ken Hechler, whose dramatic gimmicks rivaled Buffs. Lonnie Sturgill:

Ken Hechler’s the only politician that fell in and tried to do something about it. He held up this bologna over his head and said, “This is what the coal companies are trying to hand us.” Then he gave it to the guy who had the biggest family.

After the rally, the miners marched up the main thoroughfare in Charleston to the state capitol, along with their families and supporters. They crowded into the rotunda and galleries, symbolically taking over the legislature. Smaller numbers remained in Charleston in the days to come, providing a constant reminder of their strike. One legislator remembers vividly the stir the miners’ presence caused in the capitol:

The galleries were packed, there was a lot of noise, a lot of talking. It was like sitting on a razor’s edge. These guys, the miners, had been waiting in the galleries and they didn’t know what was going on. They didn’t understand about first readings and second readings and third readings and all this. Meanwhile, the big oaken doors had been shut, pulled on rollers. This wasn’t like just closing any door, you had to roll these heavy things shut. And the state police were in the cloak room in the House of Delegates, all because the miners were there.

You have to understand the situation in there. It was really getting bad. I mean, if someone had stood up and said something really inflammatory, there would’ve been a riot. So I stood up and told the Speaker, “I see the doors are closed and there’s an armed guard in the cloak room.” I said, “Open the door so I can go out, ’cause if there’s going to be trouble in here, I want to be out there with my friends.” Well, that brought down the house.

Subsequently, some kind of a bill was reported out and passed. I kind of had the feeling that bill didn’t do too much — was largely window-dressing. It was an awfully watered-down compromise. Of course, we received a lot of attention, a lot of publicity from the major news networks. But they cut the heart out of it. And the responsible people, meaning the people responsible for communication — which means the newspapers — they print a big headline, “Black Lung Bill Passes,” but they don’t say the heart’s cut out, that it’s no good, that it’s not worth a nickel.

Miners remained on strike the day after the billed passed, March 8,1969, and gathered in Beckley that evening for their final rally. Don Rasmussen:

It was at the junior high school, in Beckley. I’ve never seen a gathering like that. That place was just jammed and overflowing. Not only was it packed, but oh, the spirit! I remember there was one guy that got up and asked for a vote to go back to work. And I can’t describe it, but there was a great big roar “NO!” — that they wouldn’t go back to work. They were going to wait until the governor signed the bill.

The movement’s leaders and advisers were in a difficult position at this rally. The legislation was merely a shadow of what they had sought, but the legislature was no longer in session and the strike was already three weeks old. Craig Robinson recalls this predicament with frustration:

It was clear at the rally that the miners wanted guidance in what to do. One person got up, told them to go back to work, that they had won a great victory, that they should go back to work. And then he turned to me, and I’ll never forget it, he said, “It’s not worth the paper it’s written on.”

Nobody took a strong position in that meeting. I didn’t. I mean I made a feeble attempt. I said, “This is not anywhere near what we needed.” But it was just too heavy a responsibility on anybody to keep the strike going. They got the bill out, named pneumoconiosis as an occupational disease. Nobody was together enough to think of an alternative strategy. The thing was: stay out ’til the governor signs it. Of course he was going to sign. But they thought they’d stay out ’til then, make a big show of force.

Although the law itself was clearly inadequate, the strike and rallies marked a turning point and pulled together people who would continue to struggle for many issues in addition to black lung reform.

BLACK LUNG AND THE MINERS FOR DEMOCRACY

After the black lung strike — and partly because of it — the insurgent movement to reform the United Mine Workers of America began to blossom. In May 1969, Pennsylvania miner Joseph A. “Jock" Yablonski, drawing encouragement from the disaffection in West Virginia, announced that he would run a reform campaign against William A. “Tony” Boyle, then president of the UMWA. Yablonski paid with his life, and that of his wife and daughter, for mounting the first serious election challenge to a UMWA president in 40 years. Nevertheless resistance to the union hierarchy continued, as several people at the Yablonskis ’funeral made plans to form the Minersfor Democracy, and dedicate that organization to overthrowing the union’s top leadership and reforming its internal structure.

The rank and file’s increasing militance and agitation for union democracy and improved health democracy and improved health and safety also elicited a response from the federal government. At the end of1969, Congress passed the Coal Mine Health and Safety Act, detailing to an unprecedented degree, mandatory health and safety practices in the coal industry. The act set for the first time in the U.S. a respirable dust standard — initially 3.0 mg per cubic meter of air — designed to prevent black lung, and established a federally financed program of compensation through Social Security for disabled miners and the widows of those who died from the disease.

The confusing and arbitrary federal rules governing eligibility for these benefits left thousands of claimants bewildered and angry. With a new focus on the federal compensation program, in 1970 the black lung movement entered its second stage as several young veterans of the 1960s War on Poverty began working with rank-and-file miners, miners’ wives, and widows to form county-wide Black Lung Associations in southern West Virginia and eastern Kentucky. Often the core members of the associations were lay advocates, trained by sympathetic lawyers and paralegals to assist claimants in their efforts to obtain federal black lung compensation from the Social Security Administration.

The actual political purpose of the associations was somewhat ambiguous and later became a source of conflict: many young organizers viewed the black lung issue as a vehicle for maintaining an insurgent spirit within the union, while other activists stressed the BLAs ’ role in reforming laws and regulations governing the federal program. For the countless miners and widows to whom black lung benefits meant the difference between always doing without and a slim margin of comfort, the associations provided a concrete, much-needed service. For at least three years, until the election of Arnold Miller as president of the UMWA, the BLAs were able to pursue all three purposes simultaneously and quite effectively.

The hub of the early 1970s organizing effort was Designs for Rural Action (DRA), formed by a small group of community organizers in the spring of1968. Its founders had all been involved in the Appalachian Volunteers, one small company in the War on Poverty. They established DRA as an independent ^ organization through which they could a. raise money and continue their organizing in West Virginia. Gibbs Kinderman | was one of DRA’s founders and chief organizers:

The black lung thing, the strike in 1969, was a real spontaneous kind of thing, as far as I know. It never developed any organizational structure to keep continuing. There was no communication structure; the organization was practically gone. So we decided in DRA that our main priority was going to be the kind of thing that we knew how to do. That we could get people together, get them enough back together on black lung. But it was more using black lung to get at the union. The black lung thing everybody could agree on. We didn’t have to directly attack Boyle; you could show by contrast that the union wasn’t doing anything.

The black lung association — what was left of it — was so disorganized that they couldn’t make a decision among themselves what they wanted to do. So mainly on the staffs feeling of who would be effective, we offered Arnold Miller the job as organizer. We knew he wanted to leave the mines; he was real sick. And also Arnold was somebody — it was real obvious — who could play the leader-of-the-miners role, and was also really good at relating to and dealing with the kind of workers we would be able to recruit in the office, college students.

At the center of each black lung chapter were a few lay advocates — frequently disabled miners, miners’ wives, or widows — who were trained to counsel black lung claimants. A public interest law firm headquartered in Charleston, the Appalachian Research and Defense Fund (“Appalred”), trained many of these advocates. Milton Ogle has worked with Appalred since its inception in 1969:

People started applying for federal black lung benefits right after December 31, 1969, which was when the law was passed. As I recall, the first wave of denials came out in the fall of 70. It was pretty clear that here was a program, that if people didn’t know what was happening to them, they were going to be taken. So we sat down and talked about the black lung situation. We agreed to allocate a certain amount of money for the first training session. There were eight or 10 people there and it lasted for about six weeks. What we had was so many days a week in this office; we went through the act, the regs, how do you do interviews, get medical evidence, what do you do with a coroner’s report from somebody with a seventh-grade education who said that the man died of a heart attack. During the other days, they were out talking to people, picking up claims, and beginning to do cases.

Some who participated in the rallies and strike of1968-69 became leaders of the local black lung chapters during this second phase. Earl Stafford was one:

In Mingo County, we usually had two meetings a month, the second and fourth Saturday or Sunday of the month. There for a long time, the building would be full — two or three hundred at a meeting. Then maybe sometime there wouldn’t be so many, but they’d keep up with what was going on. Lot of people just couldn’t come out. Then we set up a chapter in Dingess ’cause it was so far for them people to come.

We did an awful lot for people, me and Carl Clark both, we represented an awful lot of people on Social Security and black lung, too. All of the hearing judges we went before said we were doing a lot better than lawyers. Said, “You know conditions, you can explain the mines better.” Lawyers never been in a coal mine. You know Jim Haviland? He’d come over here and we’d get a day care center or something like that and hold a training session. He taught us about all we know. But then he’d kid us and say, “You fellows know more about this than I do.”

The black lung chapters borrowed some pressure tactics from the welfare rights movement in their efforts to force local Social Security offices to be more considerate and accountable to claimants. Bill Weiss was a black lung organizer in Mingo County:

At first we had some meetings with Social Security in the Logan office. They had an office to handle Logan and Mingo Counties, which was ridiculous. We couldn’t even see the claims files then; we got that changed. One time, we went up there and gave ’em some demands; 30 or 40 people were involved. How’d it go? “We demand the right to be treated like human beings, not like dogs.” Social Security wasn’t prepared to administer something like that, where people knew their rights. There was all this built-in elitism. They were typical bureaucrats and resented people taking away some of their power.

National lobbying to liberalize the eligibility standards for black lung benefits brought the various BLA chapters together for strategy sessions and joint trips to Washington, DC. Milton Ogle:

From June of ’71 on up until May of ’72, there was the most effective grassroots lobbying I’ve ever seen. There were people, especially people who had gone through the training, who could cite chapter and verse of what was wrong with the law. They knew how to cite the weaknesses in the x-rays, in the cracker box breathing tests, in the mobile x-rays. There was a lot of good communication. All of these things seemed to be meshing together.

Helen Powell, a black lung leader for many years, made countless lobbying trips to Washington:

We had cars and buses going to Washington, then smaller groups going twice a month. We got donations from banks, car dealers, business people, anybody we could. We’d go in a group and just go from one office to another and not sign the guest book. If a Congress- man recognized one person, he’d think we were all from his district. You know, when you go to Washington, they don’t see you as a person, they see you as a vote.

We’d sleep in churches, or stay with friends. We ate covered dish dinners, peanut butter sandwiches. Right to this day, I can’t stand peanut butter; I walk by it in the grocery store and gag. But despite all the peanut butter and cement floors, I would do it again. I have always felt that if you can do a thing, do it.

These months of lobbying paid off in the spring of1972, when Congress passed amendments to the 1969 Coal Mine Health and Safety Act liberalizing eligibility for black lung benefits. Aware that their victory could evaporate if the Social Security Administration developed restrictive regulations for the implementation of the amendments, activists continued to lobby — this time not with Congress, but with the Social Security bureaucracy. Gail Falk is a lawyer who worked many years for black lung reform:

When the 72 amendments were passed, Social Security was writing the regs that finally came out in September. During that summer, there was this time when black lung people went to Washington and had this knock-down, drag-out session with Social Security. That resulted in the interim standards, under which many, many people were paid.

What I always thought about that was that the standards were outstandingly liberal in terms of people who were already disabled, but they let the permanent standards go, which kind of sold out the working miners for the ones already disabled. Which I think probably reflected the needs of the people doing the negotiating. Both Social Security and black lung people referred to that later and said it was the only time in history that Social Security sat down and really negotiated with black lung people.

Later that same year, Arnold Miller, a former black lung activist, was elected president of the UMWA. Other black lung leaders soon ran for district or in temational office in the newly democratized union; a few others were hired by the reform administration. Joe Malay says that these promotions had mixed results:

That black lung chapter there at Montgomery, we kept meeting there ’til Miller ran for president. After he got to be president I went to work as executive board member, and Leona Hall, she was working down in Charleston for the UMW Field Service Office. So that just about took all the people out of it. When you take away people who kind of lead the thing, you don’t get much results.

Designs for Rural Action also closed its doors after the election victory of Arnold Miller and the Miners for Democracy. Gibbs Kinderman:

I guess probably if it hadn’t been for DRA and the black lung work, the probability of Arnold Miller being elected president of the mine workers would have been a lot lower and the cast of characters running the union would have been a lot different. And then it brought people together, built collective strength to do something, changed the law. I don’t know. Kept us off the streets. It had a lot to do with our age, with the times. In terms of raising hell and causing trouble it was the most effective thing I ever worked with.

DISSENSION AND DECLINE

Arnold Miller’s election in the fall of 1972 marked the beginning of the third and apparently final phase in the recent black lung movement. Although many organizers and trainers oflay advocates either moved on to other causes or went to work for the union, others took their places. Generous “interim” benefits eligibility standards, established after the 1972 amendments, unleashed a flood of claims work and gave the Black Lung Associations a clear constituency; in some counties, the organizations were revived and new leaders emerged.

But political differences and weaknesses within the black lung movement also began to surface. On July 1, 1973, the U.S. Department of Labor began administering the black lung compensation program under relatively strict permanent standards of eligibility, and the coal industry, now potentially liable for new claims, contested virtually every application for benefits. Even a highly skilled lay advocate was hard-pressed to pursue a claim successfully; claimants turned increasingly to lawyers in what were often futile attempts to win benefits.

In addition to the burden this placed on the BLAs, there was disagreement about whether they should rely on the UMWA for money, organizational expertise, and leadership, or whether they should maintain an independent and possibly critical relationship with the union. Splits developed between UMWA members and those — such as widows — who were not UMWA members.

The BLAs ’ exclusive focus on compensation gave them a base of older workers, wives, and widows, but left the organization without a significant following among working miners, who came increasingly from a younger generation concerned about issues other than black lung compensation. Moreover, in-so-far as the BLAs succeeded in winning compensation claims and liberalizing the benefits requirements, they diminished their own base of aggrieved claimants. Each success meant one fewer person who needed the BLA. One by one, the chapters lapsed into inactivity, although even today a few stalwart individuals doggedly pursue black lung reform.

In 1973, Grant and Penny Crandall came as law students to work with the Mingo County Black Lung Association:

I’d say in 1973 the Mingo County Black Lung Association was probably in its most dynamic period, at its height. Right after the ’72 amendments, a whole lot of claims were in fact getting paid. But by 1974, the organization was a bit smaller. The same four or five people were leading it, but they were getting tired. It was all based on the ups and downs of the claims thing. They agreed to let a few older people through in the ’72 amendments, in exchange for a drastic cutoff. By 1974, it was pretty clear that they were really slamming the door in people’s feces. Once you got sucked into that — into focusing on claims — then there wasn’t much you could do. The number of turndowns was so high, demoralization was creeping in.

Benita Whitman, who was a lay advocate based in Raleigh County, has similar memories:

1969 was a mass movement, but by 1973 to 1975, people needed much more technical information. The lobbying became much more sophisticated. Some of what happened was that you had some people with a lot of knowledge, the lay advocates, but you didn’t have a broad base anymore.

Recognizing that their strategy had to change, some black lung activists tried to forge closer ties with working miners. But by 1974, the BLAs were not the only groups seeking support from working miners for black lung reform. Delegates attending the 1973 UMWA convention, the first for the Miners for Democracy, arranged for union financing of black lung claims assistance and made black lung reform their top legislative priority. In the same year, UMWA president Arnold Miller established a Field Service Office in Charleston, West Virginia, and hired several black lung activists to staff it. The relationship between these different initiatives and the actors involved in each soon grew extremely complicated and difficult. Gail Falk went to work in the Field Service Office in the fall of 1973:

Really, the first idea of the Field Service Office, it was to be Arnold’s office, and it was his office — at first. That office was to be his base in the coalfields. For the first year and a half, there were like a hundred letters a day. They all said something like, “Dear Arnold Miller, please help me get my black lung — or my pension.” Basically, dealing with the flood of letters became the principal day-to-day task of that office.

Linda Meade [first director of the Field Service Office] saw herself as identified with the black lung movement, with trying to keep it going. I don’t think she originally anticipated or saw as inevitable any split or division, because she originally had a lot of loyalty to Arnold — as a lot of people did. They thought they were friends and would have access to him. It turned out that both organizationally and individually none of those people had any access to him.

During that year, 1973, a lot more things happened. It was decided that there should be a regional black lung meeting and that was scheduled for the high school in Pikeville. In November, the second week in November. One thing decided at the Pikeville meeting was that the Black Lung Association would send representatives to the UMWA convention the next month. That convention was probably a watershed in terms of splits between the union faction of the Black Lung Association and other people. Because after the convention mandate there was the UMW Legislative Department always in the black lung business, and also that convention was a very concrete thing that sort of defined people as in or out. It wasn’t like other meetings where people could just come.

Underlying the squabbles over access to the finances and other resources of the UMWA were political differences within the black lung movement. By 1975-76, Miller’s credibility was in a nose dive, lengthy wildcat strikes repeatedly rocked the Southern coalfields, and industry officials frantically turned to manage-

merit consultants, the federal courts, and eventually a collective bargaining offensive in their search for “labor stability.”

The strikes represented in part miners’ disappointment with and rejection of established, “legitimate” processes for resolving problems — such as collective bargaining, the grievance procedure, litigation, and lobbying. Some black lung activists identified with the radicalism they believed was implicit in the strikes; others continued to support the union’s effort to lobby for legislative reform. Joe Mulloy was a working miner active in the Beckley BLA:

I remember endless debates in the courthouse down in Beckley over lobbying, strikes, letter writing. What it was was a difference in philosophy: was the Black Lung Association going to be a reasonable organization that goes for lobbying? Or was it going to be a militant, fighting organization? There was a lot of struggle around lobbying. That became the showcase of the International — lobbying — getting a bunch of crippled guys up there and march them around. There was a real difference between that kind of lobbying and the lobbying we did over getting the Department of Labor to declare a new election after Yablonski was killed. People went up and threatened and raised hell and said, “This is long enough. We’re going to shut off your lights.”

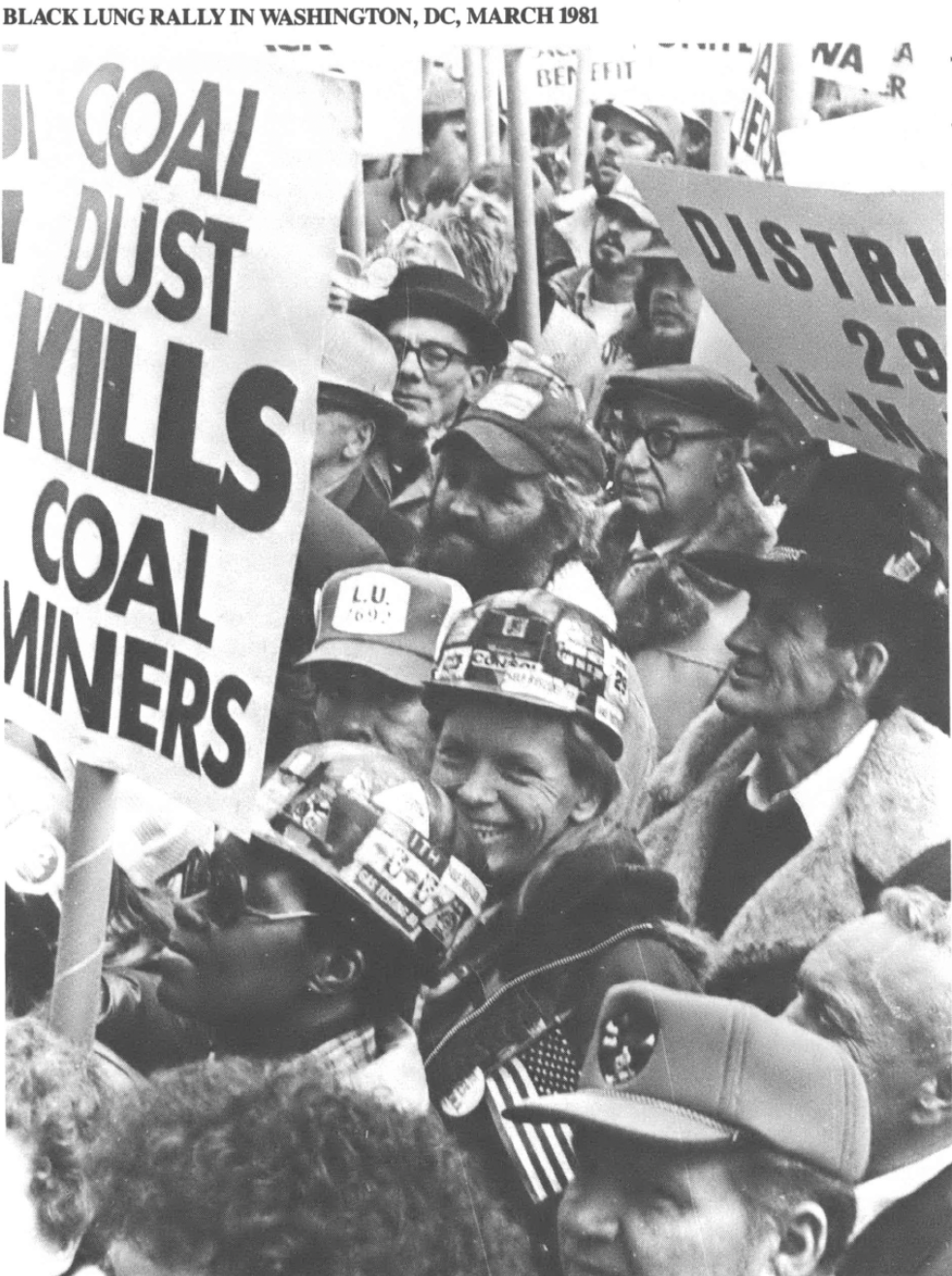

Conflicting goals and strategies within the black lung movement became unmistakably apparent in 1975-76, during a legislative campaignfor automatic entitlement to benefits after a certain number of years’ employment in the mines. When the UMWA brought 3,000 coal miners to Washington in 1975 to rally in support of the legislation, most black lung activists participated, but many were dissatisfied with the union’s role. Some felt the UMWA was undercutting their leadership on the black lung issue; others believed the union was trying to direct their activism into legal, respectable channels — that is, lobbying.

In the early spring of1976, some members of the Beckley BLA denounced compromises that had been reached in the U.S. House, and came back with their own tactic — a wildcat strike in support of automatic entitlement after 15 years in the mines. Other black lung activists, however, felt the strike was ill-timed. Confusion reigned for a week in southern West Virginia, and the wildcat strike fizzled. At the end of1976, the U.S. Senate defeated automatic entitlement in any form.

Due largely to UMWA lobbying and the persistent mystique of the power of the black lung movement, legislation expanding the black lung benefits program did pass Congress in 1978. But three years later, the reforms crumpled under the Reagan administration’s demolition crew. Today, the rate of initial claims approval is approximately 3 percent, the lowest in the 15-year history of the program. In the perverse logic of the Reagan administration, this low rate is proof that black lung is no longer a serious or widespread problem.

The setbacks of the late '70s do not diminish what the black lung movement signified and accomplished in its time. The Black Lung Associations drew together women and men, black and white, into the first mass movement over occupational disease occurring in the history of the U.S. They organized in both the workplace and the community, and successfully challenged the interlocking authority of mammoth federal bureaucracy, conservative medical establishment, and miserly coal industry. Their efforts won financial benefits for almost an entire generation of older miners and some widows, many of whom would otherwise have been destitute. As part of the larger union insurgency, the black lung movement helped to reassert the voice of the rank and file within the United Mine Workers, and to open up its positions of power to a new generation of leadership — of whom Rich Trumka, elected UMWA president in 1982, is one example.* Trumka is currently leading UMWA negotiations with the coal industry over a contract scheduled to expire in October 1984. He has a clear mandate from the UMWA convention to negotiate on the basis of no backward steps.

Those who participated in the black lung movement have drawn from it many different lessons and conclusions. If they had it to do over, some would "do exactly like we did it from the beginning.”

Others would change their tactics. Craig Robinson:

If I had it to do over, I would think more in terms of building an organization at the beginning and in terms of developing leadership, rather than concentrating on just getting things done. I fell short there in building an organization and building leadership.

Benita Whitman:

The Black Lung Association, what they did was at a time when there was a vacuum in terms of meeting coal miners’ needs and interests. They organized miners, wives, and widows in this region and represented their needs and interests. They made the coal companies accountable somewhat, but the way developed was to ask compensation for a loss. It wasn’t [to prevent] the loss itself.

Some of the brown lung people have talked a lot with the Black Lung Association and have used that somewhat as a model. And I think I would sum up after these years of involvement that that’s a mistake. You have to stress no legislative goals or you have to talk about working people or changing conditions in the workplace, because it’s always been cheaper to pay people rather than change the workplace.

The significance of the black lung movement extended beyond the coal fields. It marked the beginning of a ferment over occupational disease in other industries that continues to this day. Fifteen years ago, the grisly phrase "black lung” did not mean much to most Americans — nor did "brown lung” or "asbestosis.” Some black lung activists recently joined with workers from other industries to form a "breath of life” coalition, dedicated to preventing the occupational sources of lung disease and compensating those already disabled by it. Indeed, a feeling of firm solidarity and even personal identification with all who face workplace dangers or struggle with occupational disabilities is one of the most moving and hopeful legacies of the black lung movement. Willie Anderson:

I don’t care if it’s the cotton workers, the steel workers, or the coal miners, nothing will be done unless you have the people aroused, under their own leadership. You don’t get anything in this country unless you raise the roof off everything. And I hope they do. Because the black lung fight isn’t really effective until we all — the asbestos worker, or the iron worker, or the textile worker, or any worker in this country — get the same amount of protection, the same amount of justice. □

** In 1977, Miller headed up a new slate of candidates and narrowly won reelection as UMWA president. In 1979, ill health and the pressures of his position led Miller to turn over the leadership to Sam Church, his vice president and a former Boyle supporter. Rick Trumka defeated Church in a landslide election in 1982.

Tags

Barbara Ellen Smith

Barbara Ellen Smith is research director for the Southeast Women's Employment Coalition. (1986)

Barbara Ellen Smith lives in West Virginia and was a participant in the black lung movement. (1984)